The Cow Counties

Chapter One

Written By Michael Shannon and Minerva “Libby” Dana

After gold was discovered, the drive to progress and the action in the new state of California moved to the north. San Francisco and Sacramento grew at an astonishing rate driving the population from around twenty-three thousand statewide to one hundred fifteen thousand in less than a year.

The history of California’s counties began when the “Treaty of Peace,” the vow of Friendship, and set border limits between the United States of America and the Mexican Republic was signed on Feb. 2, 1848. The treaty ended the Mexican War and placed California under jurisdiction of the United States. Better known as the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, it was named after the city, near Mexico City, where it was signed. Treaty copies were subsequently exchanged and ratified in the Mexican city of Queretaro on May 30, 1848, and the treaty was proclaimed by President James K. Polk on July 4, 1848.

Californias first constitutional convention established a committee, chaired by General Mariano Vallejo, that considered the creation of California’s first counties. On Jan. 4, 1850, the committee recommended the formation of 18 counties. They were Benicia, Butte, Fremont, Los Angeles, Mariposa, Monterey, Mount Diablo, Oro, Redding, Sacramento, San Diego, San Francisco, San Joaquin, San Jose, San Luis Obispo, Santa Barbara, Sonoma, and Sutter.

For most of the Californios the transfer of government from Mexico to the United States would be an unmitigated disaster. Representation in the new government for Californio landowners, most of whom spoke no english, effectively neutralized their political influence. In time this would lead to the destruction of the great Ranchos. Rancheros were forced to prove that the land they owned was really theirs. The application of American property laws, administered through American courts and lawyers was decidedly one sided. Years of litigation and the high cost of lawyers all of whom were Americans advocating in American courts eventually either bankrupted the Rancheros who were then forced to sell off their land or who simply had their titles stripped away and seized by the state.

The rancheros who were American or British better understood the legal process and most of them eventually prevailed though at a financially high cost.

In the central, coastal Counties the Dana, Branch, Price, Hartnell, Sparks and the Den brothers all were granted clear title but only after a period averaging seven years.

For two decades after the beginning of the gold rush these counties were derisively referred to as the “Cow Counties.” The coastal counties were effectively cut off from the the northern and southern regions of the state. The sparse population was relatively static. Most imported goods had to come by sea to the few landing such as Cave Landing in San Luis County or Santa Barbara’s harbor.

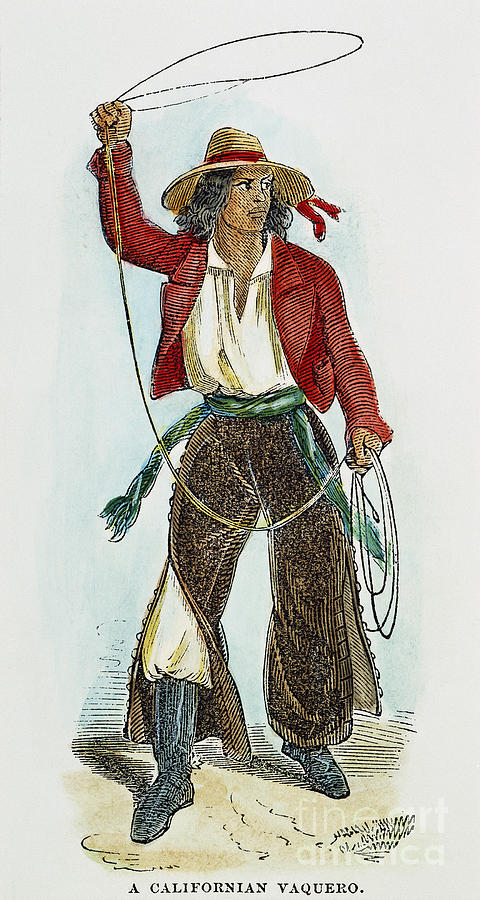

A Californio Vaquero, Granger 1852

The southern counties had no gold. What they did have was cattle. Perhaps as many as a half million by 1850 grazed the pastures of the great ranchos. They were the basis of a financial system based on trade for there was no monetary system of note until the Americans came. Dry cow hides were loaded for Boston and ports east where the were used in the manufacturer of many kinds of leather goods. In return the Rancheros received manufactured good they could not make themselves. Sparsely settled, California had no distribution system and few craftsmen. They relied on imported goods from America, China and South America.

A rancheros family might dine on fine china from Asia, wear silks and satins and read the finest books from Spain but they had no gold. The Branch family of the Santa Manuels Rancho walked on carpets from Persia. Everything had to be traded for. Separated by miles and miles of rough dirt tracks, they made the best life they could. The Ranchos were located in mostly uninhabited areas and covered vast acreages. The isolated Ranchero’s were happy to welcome travelers along the El Camino Real and Fiestas would be organized at the drop of a sombrero. Californios were famous for their hospitality and their open handedness. In the first two decades of the Rancho system, the haciendas were splendid places to visit and many young men riding the trail found their brides while visiting. By the time of the gold rush there were cousins scattered all over coastal California. They weren’t snobbish either. Many rancheros were former Mexican soldiers, or Indian Vaqueros.

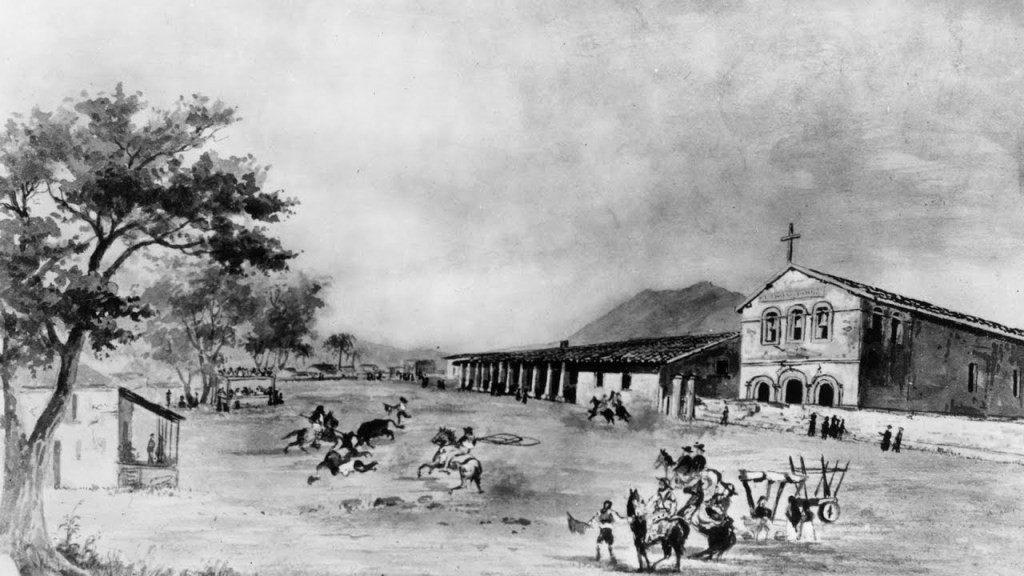

Cattle were first driven into California with the the first Spanish missionaries in the late 1700’s. Milk and cheese were produced at the all Franciscan Missions. The hides were used for shoes, clothes and dozens of other needs. The Mission fathers used the native population as labor teaching them the necessary skills to maintain the vast mission holdings. The friars did their utmost to destroy native culture, replacing it with their own ideas of civilization. Thousands of native men were trained as riders in order to control the herds of cattle because it wasn’t possible to fence all mission lands.

In between 1834 and 1836, the Mexican government confiscated California mission properties and exiled the Franciscan friars. The missions were secularized–broken up and their property sold or given away to private citizens. Secularization was supposed to return the land to the Indians. It did not. The “Neophytes” were left to their own devices.

In San Luis Obispo and Santa Barbara counties, far removed from anywhere, the year 1828 saw the first land grants. Within a few years the owners of these Ranchos took up residence. The beautifully named ranches began to appear. The Arroyo Grande, Santa Manuela, Corral de Piedra, the Rancho Nipomo, sibilant, liquid names that rolled easily off the tongue.

During the next two decades the Hacienda system was established. Homes, service buildings, bunkhouses, and corrals were put up and gradually the ranchos grew into a self supporting system which provided employment to the thousands of trained “novices” abandoned after the missions were closed. The native “Indios” intermarried with Mexican “Soldados” from the presidios and the native Californio was born. Added were the adventurers who came from all over the world. New Yorker, Francis, “Don Francisco” Branch who came overland from St. Louis with the Wolfskill party of fur trappers or Captain William Dana who came by sea from Boston. Both men ended up in Santa Barbara where they opened stores and traded in goods from around the world. Don Francisco, besides running his store, continued in the fur trade, killing and skinning Otters and seals then selling the pelts to the Russians at Fort Ross in Northern California.

Ambitious and determined to make their homes in California they both married girls from prominent Santa Barbara families. Converting to Catholicism they became Mexican citizens. This qualified them as permanent residents with all the privileges and rights that came with it, including land ownership.

By the beginning of the gold rush the ranchos along the coast were firmly established operations. Each one ran cattle herds numbering in the tens of thousands. Ranging over the verdant green hills, the Vaqueros, by now a singular breed of man, flamboyant in their dress and manner, said to never walk if they could ride, courteous to women, deadly when insulted and intensely loyal to their masters worked the ranches. They preceded the American cowboy by four decades.

Take a break from this reading and listen to Dave Stamey’s Vaquero Song. cut and paste this link to Google. Dave Stamey was born and raised on Captain Dana’s Nipomo Rancho and come by his gift honestly:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rh0DQ80kZoY

Tales of Vaqueros roping Grizzly bears with their hand braided lassos are legion and undoubtedly true. It is said that the best of them could rope a chicken on the fly. If that’s not true it ought to be.

Vaqueros lassoing a Grizzly, James Walker 1877

Near the house I grew up in are the remains of the pits used to capture Grizzlies on the Santa Manuela Rancho of Don Francisco Branch. His home was on a hill just a mile from our house. Tales of the rancho life were everywhere as many of his descendants still lived in the Arroyo Grande Valley.

In 1848 the Rancheros in the Cow Counties began gathering huge herds of the free roaming longhorn cattle in preparation for driving them up the state to the mines to sell for beef. The cattle, heretofore used almost exclusively for their hides suddenly had taken a new and potentially very lucrative value.

Great difficulties of terrain prohibited driving them north. The Cuesta, just above the pueblo of San Luis Obispo was impassable for great herds of wild, not semi—wild, but truly wild, cattle.

The Tulare Indians who had plagued Don Francisco’s Santa Manuela and Arroyo Grande Ranches, came over to the coast from the southern Jacquin valley through the Pozo, crossing the Pine Ridge and into the upper valley in order to steal horses and cattle was also not a good trail for droving.

Instead the combined herds were trailed up the Cuyama river bed until entering the Cuyama valley on the Old Chimeneas Ranch. From there the broad valley in the springtime provided enough grass to feed a moving herd. Herds from the Cuyama Rancho of Don Cesario Lataillade joined them there. Once over the ridge of the Elk Hills above todays Maricopa they crossed the valley and then turned north toward the mines.

These trail drives were just as perilous as any across Texas would be some twenty years later. Though not as wide as the Arkansas or the Red rivers the Texas herds had to cross, the Tule, the Kern, Kings, Kaweah. and Merced. If the herds trailed north up the east side of the valley into gold country they were confronted by the Tuolumne, Stanislaus, Calaveras, Mokelumne, Consumnes and the big nasty American river. All of them were exceedingly dangerous to cross with cattle and horses in the late spring when the drives took place. Vast amounts of water from snowmelt ran far across the valley before ending in Buena Vista lake or Tule lake. If the herds turned north towards Stockton, moving along the west bank of the San Joaquin River the had the shorter drive but had to sell to middlemen at Stockton for less profit.

Some of the tribes in the valley were still dangerous and had reason to be. Since the first Spanish explorer, Gabriel Moraga had made his way to the valley in 1800, the local Miwok, Paiute and Yokuts bands had been decimated by disease and killing. Taking cattle and horses for their people was practiced constantly. Rustling was very common and in the days of single shot muzzle loaders, hard to defend against.

By the 1850’s banditry had become a scourge. Immigrants of bad intent had arrived from the east coast and Australia and for a few years made San Francisco and the gold country very dangerous for a man with anything of value. Life was very cheap. In the days before photographs that could be used to identify the badman he had to be pointed out by a witness. Better to leave no witnesses. Hanging the bad man, if he was caught was a common solution. Rustlers, horse thieves, killers, claim jumpers and a host of other crimes met short thrift at the end of a rope. Hangtown in Placer county came by its name honestly.

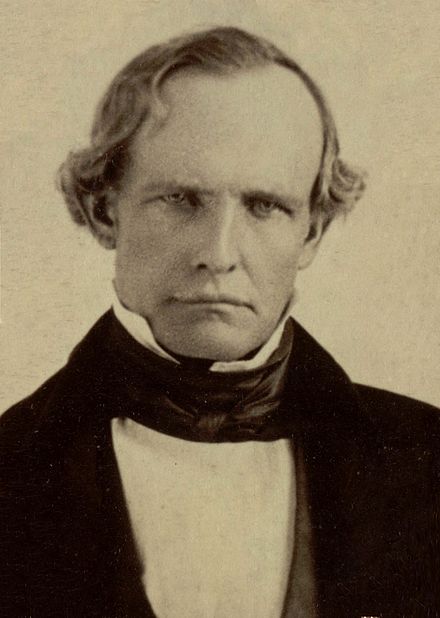

White men weren’t the only culprits either. Californios, Mexicans, the Chinese and natives were routinely dispossessed, robbed, shot, their women raped and so disdained by the immigrant American that in 1850, the first elected governor of the state, Peter Hardeman Burnett, a former Tennessean who himself had enslaved people, though he opposed calls to make California a slave state, ihe nstead pushed for the total exclusion of African-Americans in California. Burnett was also an open advocate of exterminating all California Indian tribes, a policy that continued with successive state governmental administrations for several decades, which offered $10.00 to $25.00 for evidence of dead Natives.

Burnett also proposed limiting immigration of non-citizens and expulsion of people of Mexican descent. Though forced to resign after just a year by moneyed interests in the state who recognized that all this was bad for business.

As evildoers were captured or hung, some saw the writing on the wall and slipped south into the Cow Counties where the population was small across the vast area they encompassed. With small populations still centered around the old mission churches outlaws could and did dominate law enforcement. They could and did pack juries with their own kind. Saloons and bars were numerous and populated by rough men who had no visible means of support. White and Mexican bandidos were everywhere. So much so that the tracks between ranches and little towns were sprinkled with the bones of men who had been waylaid, robbed and killed for what they were carrying.

The notorious Jack Powers, Gambler, horse-thief and noted killer lived for a time in San Luis Obispo and was reliably said to have left numerous bodies along the Camino Real.

Pio Linares, his sidekick and and second son of Vicente Linares who owned the Tinaquiac rancho in Santa Barbara county also operated out of San Luis Obispo until he was shot to death by a posse in what is now Laguna Lakes.

Tiburcio Vasquez and his gang also headquartered in San Luis Obispo. Numbering as much as twenty desperados it was a formidable group and not to be trifled with.

Salomon Pico, scion of the very prominent Pico family of old California worked from the Los Alamos Rancho. A educated landowner, handsome and dashing he is said to be the inspiration for El Zorro, “The fox so cunning and free.” In fact he was a stone cold killer and riding south from San Luis Obispo county was extremely dangerous journey for a man carrying a poke of gold received for the cattle he had sold to the forty-niners.

By night, Salomón Pico with his gang, worked the El Camino Real south of El Ranch Nipomo, ambushing men riding south from the gold fields. Many of these parties of two or three, were never heard of again after passing San Luis Obispo. In later years along the road between La Graciosa and Los Alamos numbers of human skeletons were found in the countryside with a bullet hole in the skull, accounting for the mysterious disappearances of so many. The victims were mostly Americans whom the Californios felt were enemies, and the crimes which the gang committed were never divulged by the locals, or if brought to trial, resulted in an acquittal because in this region the Californios were still in the majority and Pico was connected to its influential members. His uncle was once the Governor of California.

The gangs avoided conflicts with county officials, who in turn seemed to let the bandits alone. Protected by a local population who resented the intrusion of the Americans they were difficult to capture.

During the early gold rush there were no towns of note between Monterey, the old Mexican capitol and San Luis Obispo. Returning south up the Salinas valley, where pioneer writer Alfred Robinson noted that the wild country between that town and the Las Animas Rancho of Don Jose Mariano Castro (Gilroy) where one could be assured of hospitality, was so wild, the trail only as wide as a single horse and the stands of chaparral, willows and native grasses were as high as a mounted man’s head. To ride alone was to risk your life. Another days ride and a stop at Rancho Posa de los Ositos and Don Carlos Cayetano Espinoza at todays Greenfield then on to the Old Mission San Antonio. San Antonio mission itself was the scene of a brutal and Horrific series of murders.

As the gold rush was going on, a lot of precious metal was being shipped up and down the coast of California. William Reed along with his family bought the old mission and set up boarding house for travelers along the old Camino Real. He took payment for food and lodging in gold. The dust and nuggets were buried somewhere on the mission grounds for there was no other place of safekeeping.

The death of the Reed family, their employees and servants is an example of the dangers of living in the Cow Counties in what were later called the “Bloody Fifties.”*

A group of travelers who spent a night at Reed’s included a man named Joseph Peter Lynch who had deserted from General Kearney’s command at Fort Leavenworth, and Peter Raymond who was an escaped convict and murderer already, having committed murder in the gold rush town of Murphys. These two had killed and robbed two Americans who they had encountered while traveling south from the bay area. While at La Soledad Mission, they teamed up with two deserters, one named Peter Quinn, the other Peter Remer who had jumped ship from the British warship HMS Warren, docked in Monterey Bay. Lastly, there was Sam Bernard who was accompanied by a Native American boy known as John, who was fleeing the Soledad Mission. This group arrived at the San Antonio Mission on December 4th, 1848.

The group left the next morning. Realizing that Reed must have more gold hidden at the mission, they soon returned. Reed denied the existence of the gold. One of the men, Sam Barnard, pretending to get more wood for the fire went outside, returned with an axe, and hacked Reed repeatedly. Mortally wounded and bleeding from horrific wounds he was dispatched by the Indian Boy John who stabbed Reed with a knife until he was dead. The group then went through the Mission murdering the rest of the occupants who ran screaming trying to get away from the killers. Antonia Reed, pregnant was brutally struck down. Four other children died. As many as eleven people were slaughtered, including Reed, his family, servants, and guests. The bodies were dragged to the old carpenter shop and thrown in a heap. They were all eventually discovered by a mail carrier named James Beckwourth. They were later buried in one large communal grave at Mission San Miguel.

Two nights after the killings, the group camped for the night at the Corral de Piedra rancho in the area of the Corralitos, in the Arroyo Grande valley, less than mile from the home of Don Francisco Branch and his family.

A 37 man vigilante group chased the men down at the crown of Ortega Hill, overlooking the present town of Summerland. Bernard was shot and killed, John the native boy ran into the ocean and drowned. Peter Quinn was wounded and captured; Joseph Lynch and Peter Remer were also captured, and later confessed their crimes. Joseph Lynch, Peter Remer and Peter Quinn were executed by firing squad, in Santa Barbara, on December 28, 1848, near the corner of De la Guerra and Chapala Streets. They were buried in the cemetery of Mission Santa Barbara.

For thirty years, beginning with the gold rush the Cow Counties were a very dangerous place. The only justice was vigilante. It took many, many years to rid them of the scourge of those evil men. When my own grandfather was a boy in the 1880’s, south San Luis Obispo county’s supervisorial district was still commonly referred to as the “Bloody Fourth.”

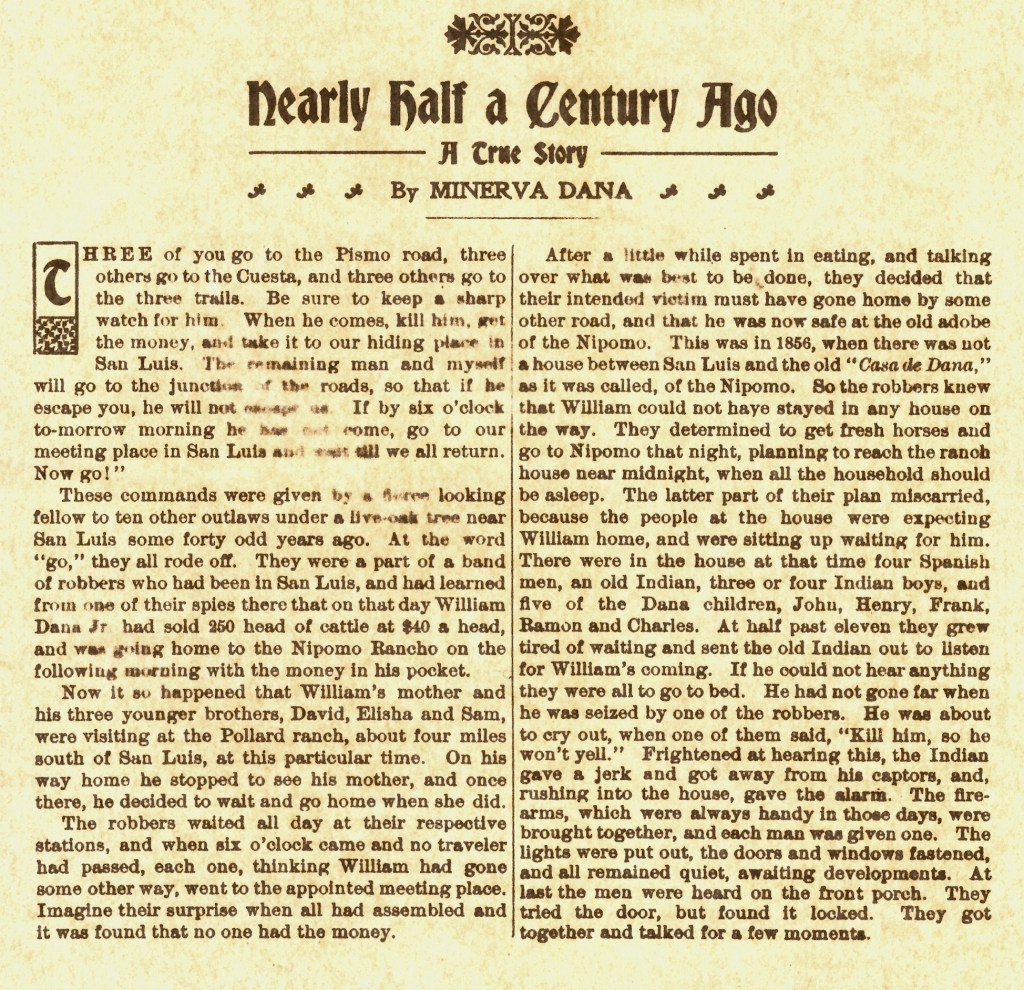

The following is an article written by my grandmothers classmate at Santa Maria High School in 1904 and published in the High School Revue. The author is Minerva Elizabeth “Libby” Dana, Granddaughter of Captain William Dana owner of the Nipomo Rancho in southern San Luis Obispo county. The story she relates takes place in 1856. William Dana Jr was her father Davids brother. Though just seventeen when she wrote this account she speaks as if she was a participant. It’s a family story of the best and truest kind.

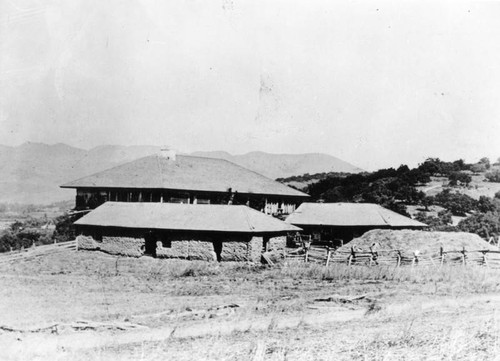

Rancho Santa Manuela, Don Francisco Branch and most of his descendants are gone. Casa de Santa Manuela has long returned to the good adobe earth from which it was built but the family of Captain William Goodwin Dana still own the remnants of Rancho Nipomo and play a prominent role in the little town of Nipomo California, and yes, there are still cows in the hills of the Cow Counties.

Looking much the way it did in 1856 the old adobe has been restored and is open as a museum. Visit when you can. The spirit of hospitality still abounds on El Rancho Nipomo.

Note: *Bloody Fifties they were. Uncounted people were murdered for their goods. The phrase “Dead men tell no tales” effectively describes the M O of the Desperados of the time.

Michael Shannon is a World Citizen, Surfer, Sailor, Teacher, Builder and Story Teller. He lives in Arroyo Grande, California, USA. He writes for his children.

E-Mail: Michaelshannonstable@Gmail.com

Minerva Elizabeth “Libby” Dana was the granddaughter of Captain William Goodwin Dana. Her story was printed in the Santa Maria High School Review in 1904. She was a classmate of my grandmother who was born on the Punta de Laguna Rancho of Don Luis Arelanes near todays Oso Flaco in northern Santa Barbara and southern San Luis Obispo County. Though the Ranchos are gone my family still lives on the Santa Manuela and my grandparents lived on the Bolsa de Chamisal.

Wonderful stuff! Great writing and so informative.

LikeLike

I never knew of this History of Old California!

LikeLike

A good factual book with first person experiences is: “Letters From California,”1846-7 by Donald Monro Craig, U of Cal Press, 1970. ISBN: 0-520-01565-7. It’s written from letters created by a British whaler named William Robert Garner. As a kid growing up in King City,Monterey County ,the Garner kids were my playmates who lived a block away from our house. Two hundred sixty two pages with an excellent index.

LikeLike

Thank you for the tip, I’ll check it out.

LikeLike

Go to bookfinder4you. If you have problem I have a couple of these books because these were my playmates and I provided one of them (Annie Garner Garcia/ the oldest garner, garcia ,playmate) one of these books. I’m sure she is still alive. She is a sharp cookie. Russ

LikeLike