If you think you don’t know your parents life before they had you, you’re right.

My dad was a good boy. He was a good man too. He followed the rules even if he didn’t like them. He did what his mommy asked him to do. He got rid of the goat when she said, “Only shanty Irish keep goats,” even though he loved that goat and told stories about it all his life. He really wanted to do good. Sometimes, though, it was just impossible.

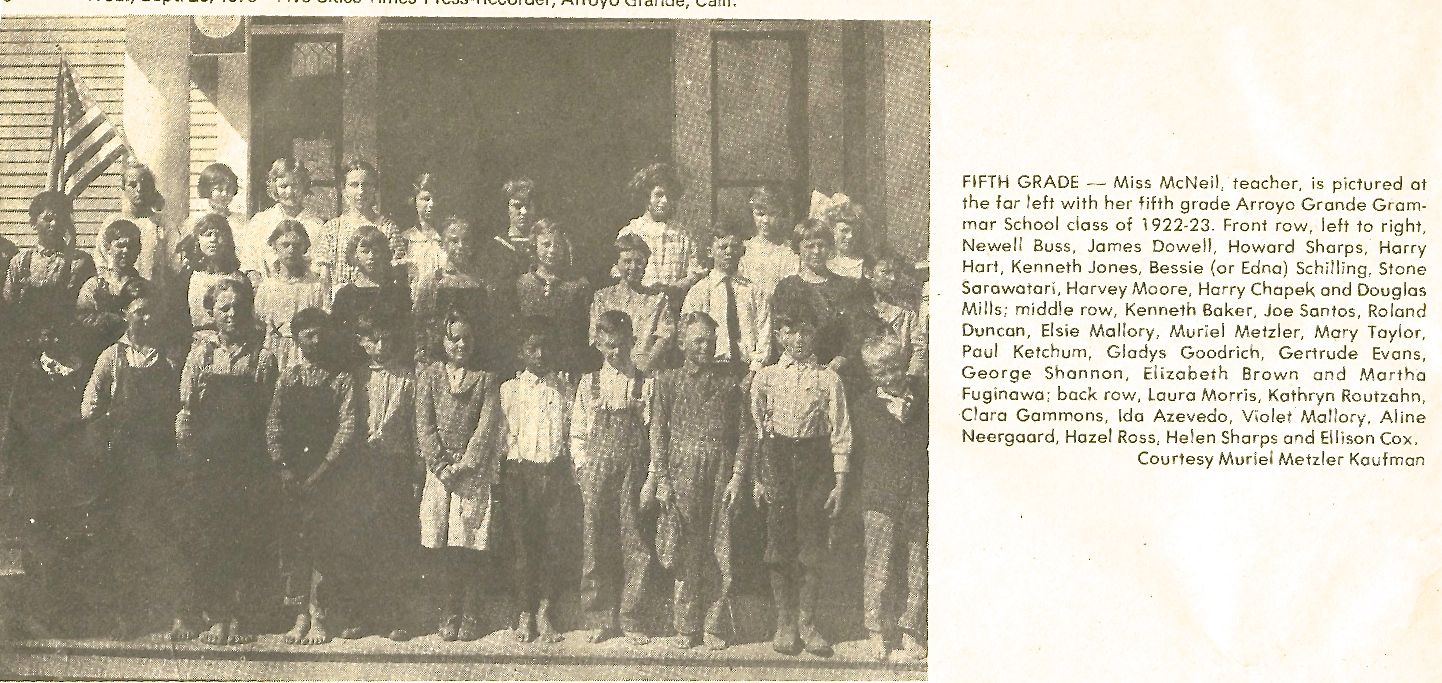

He noticed the plume of smoke through the open schoolhouse window and quietly elbowed his friend Kenny Jones. They watched from the corner of their eyes until suddenly a burst of crimson flame framed in black, oily smoke shot up from behind the trees that surrounded the old Arroyo Grande schoolhouse yard. It was too much to bear. Miss McNeil had her back to the class so they made a break for it, jumping out the window and hightailing it for the fire. Behind them they could hear Muriel Metzler hollering at them to come back. “Miss McNeil, Miss McNeil, George and Kenny jumped out the window, George and Kenny jumped out the window.” Miss McNeil flew to the window but she was too late, the boys were gone.

Arroyo Grande Grammar School Staff 1925-25

Sitting, l-R Miss Phoenix, Mr Faxon Principal, and Miss Righetti, Standing l-R Miss Doty, Miss Wimmer, school nurse, Miss McNeil, Miss Walker, Miss Lambeth and Miss Cotter

It was Fred Marsalek’s home. They had just moved there from the Oak Park area the year before. They farmed Walnuts on nine acres of land they bought from John Huebner. The farm was about a half mile from school as the crow flies and fly those boys did.

With just a population of around 850 people Arroyo Grande was a pretty typical small farming town in the mid 1920’s. The main street had recently been paved and concrete sidewalks replaced the old wooden ones. There were some new, but dim, street lights on Branch St, but everywhere else, particularly on those moonless nights you had to know where to put your feet. Some things had changed, boys, mostly wore shoes to school now. They were more likely to go on to high school than their fathers. Dad’s father, Jack Shannon dropped out of school in the 8th grade in 1896. Boys were expected to work then. At 14 you would have been expected to do a mans work. For a number of years there was no high school in Arroyo because the principal taxpayers, mostly farmers didn’t see the need for schooling boys and refused to pay the school tax. My grandmother Annie, went to Santa Maria HS though she lived in Arroyo Grande.

Electricity was common and indoor plumbing had been installed in most homes, though not in my grandparents house. That wouldn’t come for another year and even then my grandparents had to pay for the lines to be strung out from town. The juice went to the dairy they owned in order to operate the sterilizer, pasteurizer and the milking machines. It would be 1925 before they had electricity in the house at the foot of Shannon Hill on the Nipomo road. No one had radios yet, the first radio broadcast in the country was radio KDKA in Detroit in 1920, and that was a long way from Arroyo Grande. Radios were considered so important that they were an item on the 1930 census forms. If you wanted news you read the papers. There were two in Arroyo Grande and the Los Angeles and San Francisco papers were delivered each day by train.

There were still saloons even though it was an “officially” dry town and had been since 1911 when the city was incorporated by a vote of 88 yeas to 86 nays. There were a few dozen residential lots, clustered mostly on the east side of Bridge Street. The rest of the area was dotted with small farms, it was a pretty quiet place to grow up.

Fred Marsalek grew artichokes, peas and had walnut trees, which were a big crop in those days before the development of efficient railroad refrigerator cars which changed farming from dry crops to the fresh vegetables that we know now. Entire families lived on small acreages which wouldn’t be profitable to farm today. People still kept chickens and many had milk cows. There were barns behind most houses because the day of the horse wasn’t over yet. Many farmers still used them for cultivation and pulling wagons and buggies. Fred didn’t buy his first auto until 1929. Valley road was just a dirt track and would have been nearly impassable when it rained.

On that day, dad probably rode to school with Newell Buss and his brothers, They came down from their ranch behind Mount Picacho, picking up my dad and uncle at the dairy. A buckboard full of young schoolboys pulled by a tired old horse who spent the school day hitched to a post in front of the school, a nosebag of grain hooked behind his ears, swishing his tail at the occasional fly.

Kenny Jones would have walked from his house on Myrtle street. Drifting toward school on the footpath that would become Poole St. but at that time just wide enough for a couple of kids to walk side by side. The crowd grew larger as they passed the McCoy’s, and the Bardin’s before crossing Bridge St. to the grammar school. Kids coming down Pig Tail Alley and from the Phoenix, Harloe and Costa places or the Runels and Conrow ranches down the valley, funneling in the door before the final bell rang.

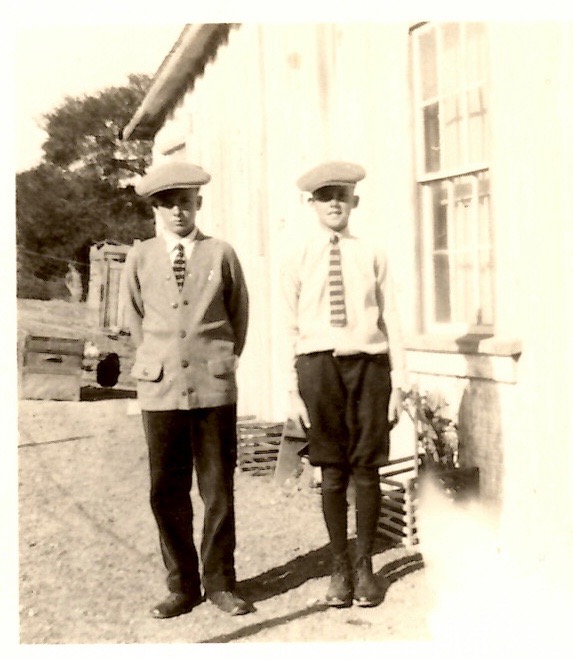

Kenny,s father Fred was a farmer and horse breeder, the grandson of Francis Ziba and Manuela Branch. You can’t get more local than that. He and my dad were best friends all through school. They went to grammar, high school and the University of California Berkeley together, even joining the same fraternity.

That was the future though. This day was about Fred’s house. They ran as fast as they could down the rows of pea vines, careful to stay in the furrows because, as every farm boy knows, you never step on a plant, that’s your living right there. Ruining crops was a bigger crime than ditching school.

The hollering from the school died down as they distanced themselves from the school and drew closer to the Marsalek’s burning house. It was already old in the 20’s and dry as a bone. Built of redwood from Cambria, those old houses, once the wood dried out were like tissue paper when they burned, fast and hot. The volunteer firemen arrived just in time to sprinkle the ashes. Surrounded by a few pieces of furniture and keepsakes they had managed to drag out of the burning building, Albina quietly cried.

After the fun was nearly over, the chief of police, Ben Stewart scolded the boys and ordered them back to school. Now, Ben was more than just the chief, he was the town tax collector and the city clerk. A little officialdom went a long ways in those days, but his word was law and dad and Kenny had to obey. Besides, Ben played poker with my grandfather and dad knew there was no escape.

So they slunk back to school. They were going to have to face the “music” as the old saying goes. Miss McNeil sent them to the principals office while Muriel and Bessie snickered behind their hands. The boys were secretly envious of course and wished they had gone to such a big event. Kathryn turned to her friend Mary Taylor and said in the superior way that girls have always had, “Those two are going to get what for alright.” They went down the hall past Miss Phoenix and Miss Walker’s rooms, Miss Doty and Miss Righetti had their doors open also and the sibilant hiss of giggles followed them right into the Mr Faxon’s office.

Mr Faxon taught eighth grade, as well as being principal, so he told they boys to sit down and wait and he would be right back. Dad and Kenny sat, fidgeting in their chairs imagining the fruits of their little adventure; the dire circumstances they found themselves in. Soon, Kenny started tapping his feet in an insistent rhythm and he turned to dad and said, “George, George, I gotta poop but I’m scared to leave the office.” Dad said he should use the principals toilet which was right there in the room. Kenny looked around, didn’t hear any footsteps so he quickly darted in and closed the door. Dad could hear the sigh of relief behind the door and a few minutes later the door opened again and Kenny came out, surrounded by a horrible miasma, a stench of the worst kind. Now dad grew up on a dairy and he knew smells, and this one was epic in its proportions, nearly making his eyes water. Kenny sat down and a moment later Mr Faxon came sailing in the door ready to do business. He suddenly skidded to a halt, looked at the two boys, then ran to open the windows. He stood with his head out the open window, then looking back over his shoulder he eyed both boys, he paused a moment ad then he said, “You boys get out of here, get back to class.”H e followed them out into the hall, carefully closing the door behind him. George and Kenny scurried back to class and nothing more was ever said about it. For several days the principal spent very little time in his office. The boys considered it a miracle. They were heroes.

The Arroyo Grande School, Bridge Street Arroyo Grande California circa 1920.