By Michael Shannon

Part The Second

Graduation came in May of 1908. After four years of study, the death of her uncle Patrick Moore in 1905 and the following year the great San Francisco Earthquake, Nita walked onto the stage at the Greek theater, accepted her diploma from Benjamin Ide Wheele

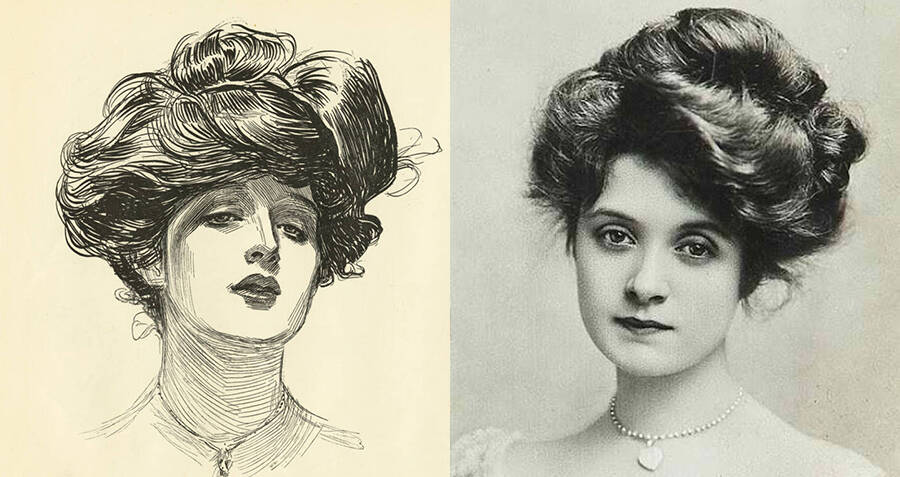

Commencement week, a round of celebrations, fraternity and club open houses, receptions and Class Day concluded on Wednesday with graduation. Faculty, regents, honored guests and alumni met at North Hall and the Library.led the graduating class up to the Greek Theatre. Dressed in their finest, the boys in high starched collars, the girls in their finest formal gowns. Their chin high lace collars stitched with traceries done by hand with initials worked as was Nita’s. The silk and chiffon fabrics used for the long narrow skirt ended three or four inches above the waist line and was held by a belt of stiff Petersham Cotton tied with a large bow in the back. The girls wore their hair up in the style of the Gibson Girl. Rolled and fluffed held by pins exposing the neck, the style was considered the height of elegance for young women.

The Gibson Girl had an exaggerated S-curve torso shape achieved by wearing a swan-bill corset. Images of her epitomized the late 19th- and early 20th-century Western preoccupation with youthful features and ephemeral beauty. Her neck was thin and her hair piled high upon her head in the contemporary bouffant, pompadour, and chignon, the “waterfall of curls” fashion. The statuesque, narrow-waisted ideal feminine figure was portrayed as being at ease and stylish.

The illustrator Charle Dana Gibson is credited for popularizing the standard look of the girl. Many women posed for Gibson Girl-style illustrations, including Gibson’s wife, Irene Langhorne, who may have been the original model. Irene was a sister of Viscountess Nancy (Langhorne) Astor. Mrs Astor besides being the first female member of Britain’s parliament was equally famous for her sharp tongue and took great pleasure in skewering Winston Churchill with it on every possible occasion. During a dinner party she informed Churchill that, “If you were my husband I would poison you,” to which he replied, “If you did madam, I would take it”. He could give as good as he got.

The Langhorne girls were immensely rich and two bought husbands with titles, Viscount Lord Waldorf Astor son of the richest man in the world at the time and Robert, the first Baron Brand. Wealthy American girls who married poor but titled Englishmen were titled by the American press as the “Dollar Princesses.”

The most famous Gibson Girl was probably the American-British stage actress, Camille Clifford, whose high coiffure and long, elegant gowns that wrapped around her hourglass figure and tightly corseted wasp waist defined the style. Miss Clifford also made popular the oversize woman’s hat known at the “Merry Widow.”

Irene Langhorne Gibson. The Original Gibson Girl. Public Domain print.

In Gibson’s drawings there was no hint at pushing the boundaries of women’s roles; instead they often cemented the long-standing beliefs held by many from the old social orders, rarely depicting the Gibson Girl as taking part in any activity that could be seen as out of the ordinary for a woman.

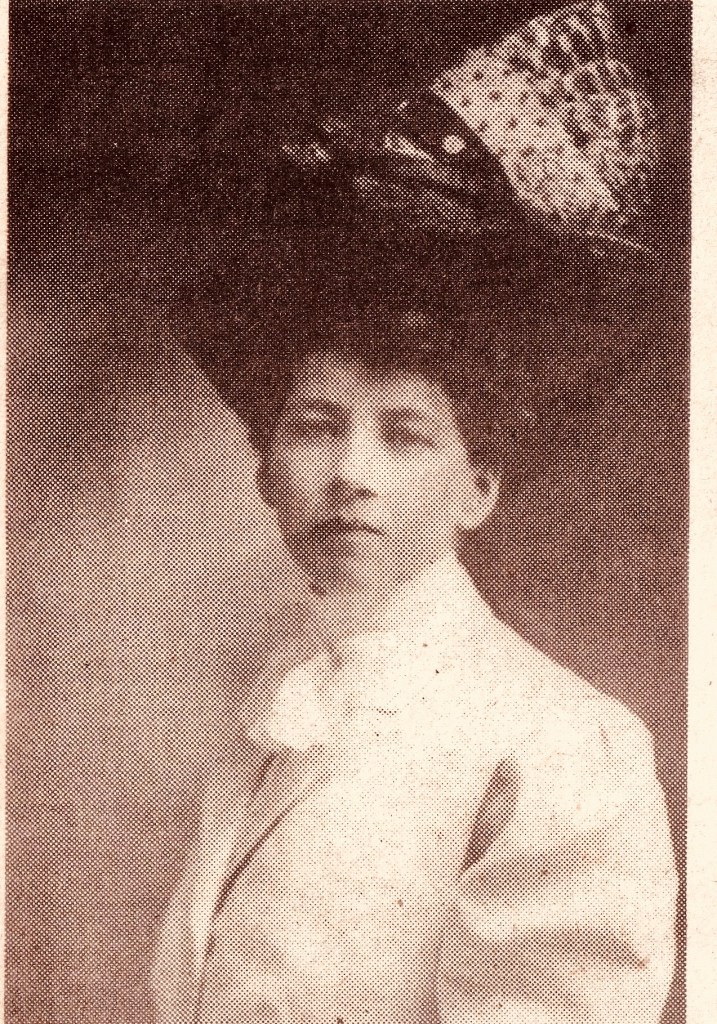

Nita and her friends certainly were aware of these trendsetters as any young woman of today would be. Women’s magazines, films and books held them up as ideals and in the old family photos of her at this time of her life she epitomized the look. Popular culture was alive and well in 1908, even in tiny Arroyo Grande where she was from.

Nita always seemed to me a serious woman but once she explained to me why she had a thoroughly beat up plug hat hanging on the hatrack in her office. You see, it was the fancy of students who attended the University of California, Berkeley at the dawning of the twentieth century to wear them. Upperclassmen and women, of which my grandmother was one, wore the old beaten up hats as a fashion accessory, much as my father wore his beanie when he was a student at Cal in the 1930’s. They must have found them on trash heaps or second hand stores, useless to anyone but college students who delight in being contrarians. My grandmother and her friends would walk around campus, from the North Hall to the Bacon Library Hall, or gather at the Charter Oak, dressed in the style of 1908, wearing shirtwaists, high collars and long dresses over high button shoes. The stately look we imagine today as being their nature. It’s too easy to forget that they were twenty year old girls. Just as they are in college today, full of high spirits and dreams of a life yet to be lived.

Photo, Calisphere

Each senior draped in a blue university gown, the mortar board with its golden tassel swaying in time with the march as they made their way to their seats for the ceremony. The sound of sibilant silk and cotton dresses, the soft clack of shoes on pavement accompanied the students like an orchestra. In the gentle breeze coming up from the bay, the mingled scents of cologne and perfume heralded the coming of the graduates. Nita sat between Laurence Herbert Grant, his winged collar and cravat complete with stickpin marking him as a bit old fashioned. He would move up to Fort Bragg and join the clergy. He looks a serious young man with his earnest expression, his thick wavy hair ruffling in the breeze. On her other side, Sydney Baldwin Gray, She of the small round glasses. She has the competent straight forward look of a teacher which she went on to be. Next in line, Ruth Van Kampen Green, married right after graduation. Her husband worked for United Fruit as a packer and she ultimately bore him eight children and spent a good deal of her life in Mexico and Brazil. They followed the banana trade. Next to Ruth was Edith Montgomery Grey who became a third grade teacher at Oak Park primary school in Folsom California. She resigned in 1920 in order to marry. Expectations were such that women should not have a career other than be a homemaker. She died soon after childbirth in 1920

A large majority of the women became teachers. Superbly educated, graduates of Cal were a hot commodity. California was growing rapidly and desperately needed more educators. Just as today, they found their way to the Normal School, Santa Barbara College , todays UCSB where they took a course of study to prep for the state teachers qualifying exam. These women were not the one room schoolhouse teachers of popular fiction. The California State Teachers exam of 1910 was brutal and was the equal of modern teachers requirements. Just as today, it took a five year course of study to qualify for a credential.

The college of Social Sciences at Berkeley, Nita’s school, was the largest at Cal in 1908, numbering over one thousand students. A student was promised a first class education just as they are today. She was required to have taken Latin at Santa Maria High School though Cal did not insist on Greek for the College of Social Sciences. She had a wide choice of classes in humanistic studies. She could choose classes in the great field of literature, linguistics, history and economics. Geography and education were also requirements and from the list of women graduates it can be seen that the most likely career was education.

Her curriculum shatters the old saw about the schoolmarm and the one room schoolhouse. One of the orphan girls Nita was raised with who was also schooled by uncle Patrick Moore, Mamie Tyler took her degree at a school founded as a private institution, ‘Minns’ Evening Normal School founded in 1857. That school became a public institution by act of the State Legislature on May 2, 1862. In 1868 the board of trustees took up the matter of permanent location, and Washington Square in San Jose was chosen. Mamie graduated in 1900 and taught much of her career in a log cabin near Port Angeles, Washington State.

Martha “Mamie” Tyler Kolloch and her students at the log cabin school in the Olympic forest Washington State, 1921 Shannon Family Photo

The first in California was originally founded as a private institution, ‘Minns’ Evening Normal School,’ in 1857, the school became a public institution by act of the State Legislature on May 2, 1862. In 1868 the board of trustees took up the matter of permanent location, and Washington Square in San Jose was chosen. San Jose State Teachers College was born. The Normal Schools were changed to state colleges in 1935 which allowed them to offer degrees in subjects other than education. Those schools make up the majority of the original California State Colleges including UCLA, San Diego State, UCSB and San Jose.

Normal Schools derive their name from the French phrase ecole normale. These teacher-training institutions, the first of which was established in France by the Brothers of the Christian Schools in 1685, were intended to set a pattern, establish a “norm” after which all other schools would be modeled, a pattern which has remained in effect until the present day.

Wether Nita’s goal was to teach we don’t know but many of the girls sponsored by Patrick Moore did become teachers. Education was important to the Moore’s and Nita’s parents, the Grays. Her entire extended family was made up of Irish immigrants for which education was the most cherished goal. A goal still shared by immigrants from all over the world.

Nita’s parents, her siblings, and friends had arrived in Oakland by train from home and waited anxiously in the tiered seats around the Theatre where the folding chairs awaited the arrival of the dignitaries and expectant graduates.

Baccalaureate, also in the Greek had been on Sunday in which Bishop Nichols sermon had emphasized the opportunity for “Men” of character and worth to make their stamp on the great state of California. No mention of women in 1908.

Class day on Monday saw seniors meeting at Senior Oak. A speech by class president Hartley followed by the progression of “Plugs and Parasols” which wound through the campus where they halted for speeches by fellow classmates who spoke on subjects they were most interested. Hardly anyone listened of course. Excitement was building to a fever pitch. Tuesday afternoon they sat for the final Symphony Concert of the year. Finally the last senior assembly in Harmon Gymnasium on Tuesday evening. Parasols were folded and Nita and her roommates went home a tried to get some sleep. Wednesday would be an early start. Gowns to be pressed, hair done up, shoes polished and then the process of dressing, the girls helping each other, pushing pulling and primping making everything “Just so.”

Wednesday, the graduates to be met and organized themselves for the procession up to the Greek. Waiting for the ceremony to begin was almost more than they could stand. Nervous chatter rose above the crowd, the occasional group of boys hooped and hollered to let of steam but finally, lined up in proper order they stepped out to the sound of the University Band and began to walk.

At the Greek they filed into the rows of chairs, carefully arranged in alphabetical order. The murmur of the crowd was underplayed by the chairs creaking as the soon to be graduates took their seats. The rise and fall of low voices marked the expectant crowd. For many this ceremony would be one of the highlights of their lives.

After the always interminable speeches, after four years of University life, Nita rose and joined the parade up the steps onto the stage at the Greek Theatre and received her diploma from the hand of President Benjamin Wheeler himself. Then polite congratulations from Mrs Hearst and the other regents and with that her book of education closed.

The “S” curve is still the mode for women in 1908 and the cut of Nita’s clothes emphasize that. Shannon Family Photo

And here’s to the ‘Naught eight co-eds, Our prettiest, sweetest and best.

Whose eyes laugh back with our laughter, Whose hearts glow warm with our zest.

To the girls who were women at entrance, But who will be girls ’til they die.

A toast! For we know they are loyal.

A toast! With our glasses held high.

For a final deep pledge to our class, boys

O a fig would we care for fate!

In the same old way we would drink to our class,

In a toast to old “Naught-eight.

From the Blue and Gold Yearbook, University of California Berkeley class of 1908 by Sheldon Chaney, ’08

Coming next: Nita, the third. Senior trip to Yosemite Valley.

Please Like and Follow.

Many thanks to my researcher Shirley Bennet Gibson from another old time local family. Couldn’t do it without her.

Michael Shannon is a surfer, traveler, teacher and writer.