By Michael Shannon

Just a regular Tuesday. The only two 8th grade girls in our little school. They were the Judy’s, one Gularte and one Hubble. Dressed in their skirts buoyed by crystal white petticoats, looking like upside down Chrysanthemums they huddled around the little portable 45 RPM record player in the corner of the classroom with their friends Jeanette, Cheryl and Nancy, they were playing and listening to a very popular song. The volume was low as Mrs Faye had asked them. They were crying, for the music that had died the night before in a scraped over cornfield in winter’s Idaho. A cheap little puddle jumper aircraft, 21 years old flown and by a 21 year old novice pilot had gone down killing all aboard. That old Beechcraft, worn out and dangerous to fly, especially with a low ceiling and swirling ground fog had slammed into the iron hard frozen ground, killing Richard Valenzuela of Pacoima, California, instantly. All the dreams of a poor barrio boy went with it.

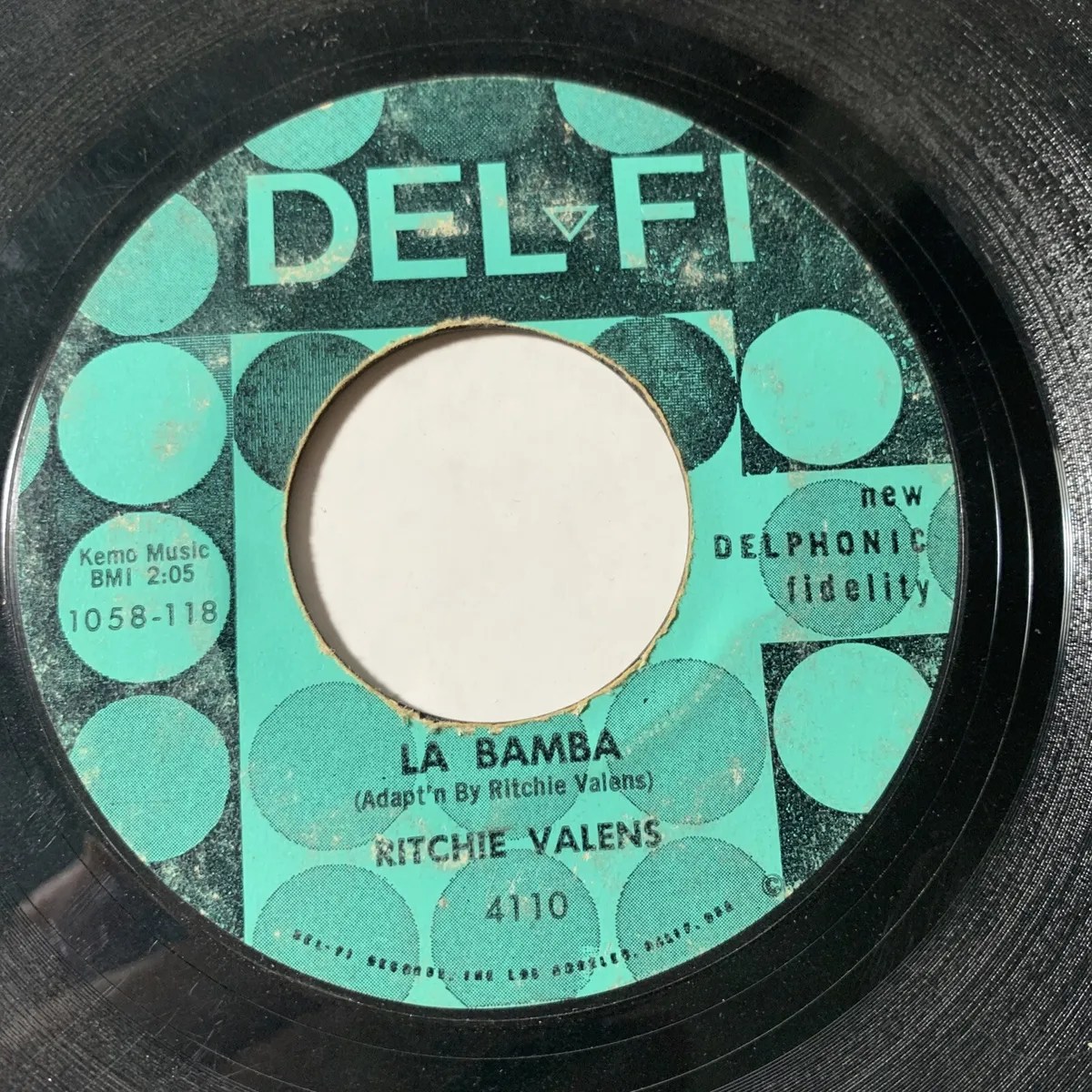

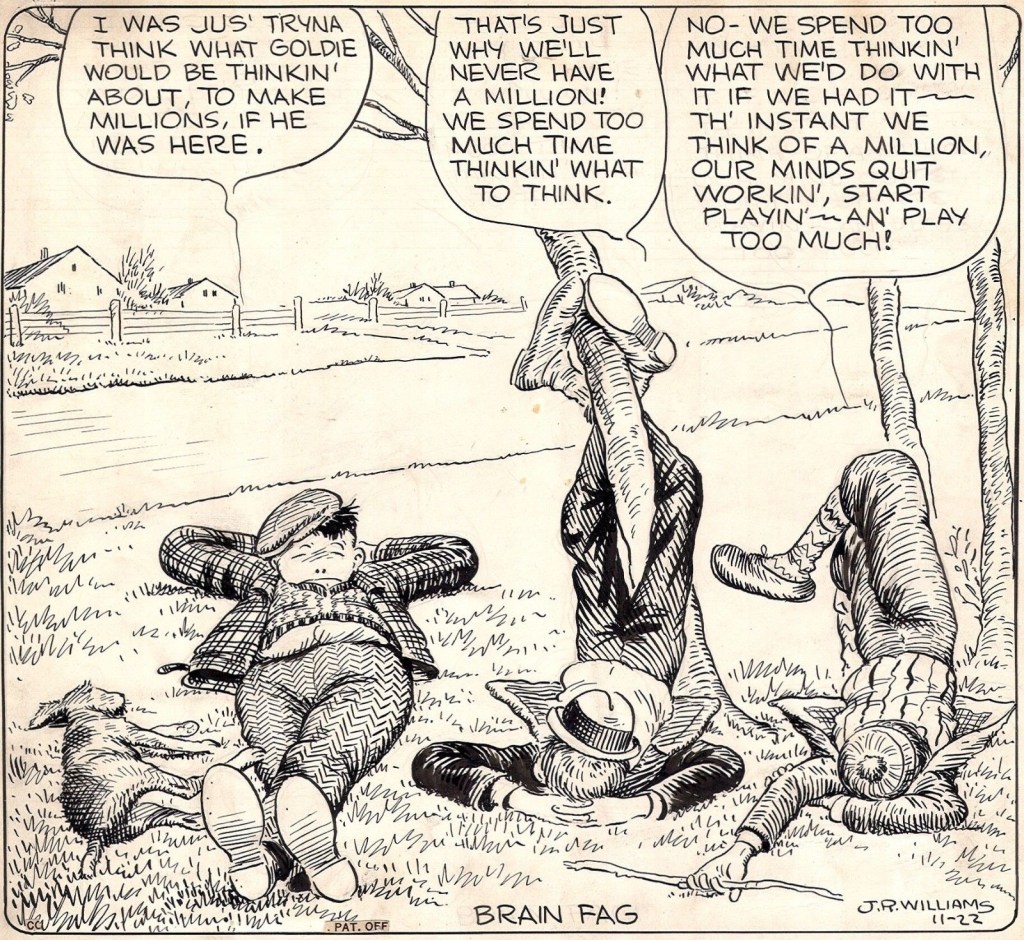

Not one kid in that classroom could have imagined that the little tune, La Bamba would be immortalized by the tragedy of a seventeen year old boys death. But it was.

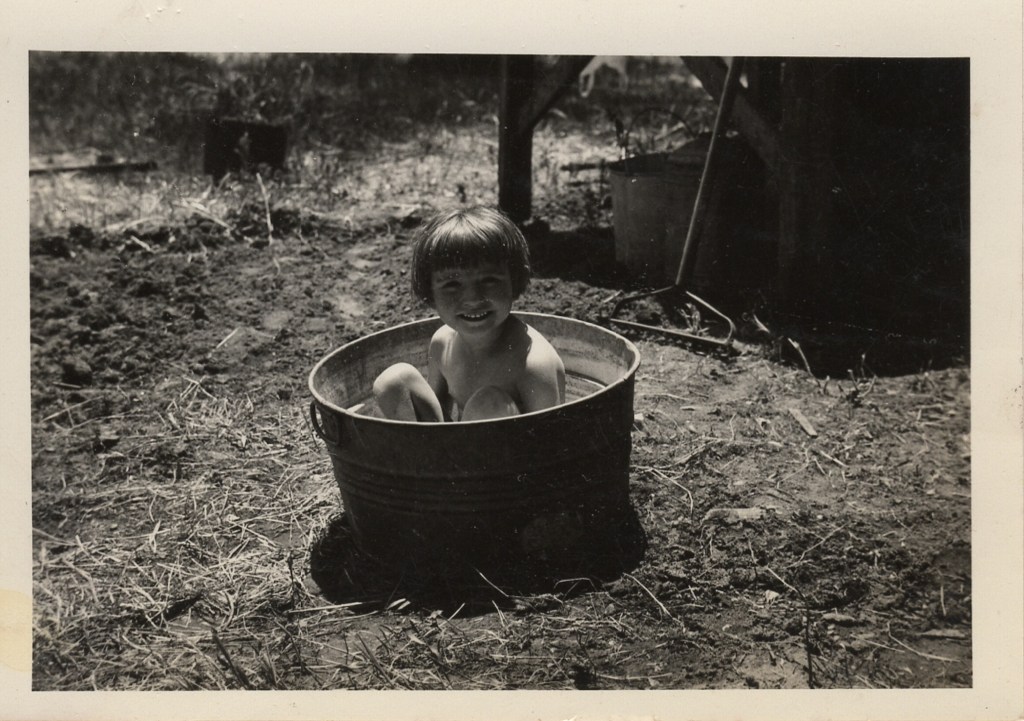

Valenzuela home movies. 1957

Don McLean, who wrote the greatest damn rock-and-roll tribute song of all time—the rhapsodic, rambling, profoundly metaphoric history of American rock from his self-proclaimed “Day the Music Died,” a concert about Buddy Holly, Richie Valens and the Big Bopper’s plane crash. MacLean is the ultimate rock-and-roll outsider. No Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, no mega-shows in Vegas, just the guy Bruce Springsteen said was his greatest musical influence. For what are musical lyrics but storytelling.

After all, it used to go without saying that rock-and-roll was the musical expression—the voice, if you will, of the American angry young men (and women) of the 1950s and ’60s—those same rebels without a cause that McLean describes as wearing “a coat they borrowed from James Dean.”

I look at it and marvel – what’s their dream going to be? My dream ended with a lot of sixties’ assassinations. It didn’t have to end. It didn’t get a chance to play out as it might have. Someone else’s dream put paid to it.

Music, iconic songs, capture a time in the way an academic historian never could. Ritchie’s little ballad lives forever, even if he didn’t.

Richard Stevens Valenzuela’s name rolls of the tongue particularly when pronounced with the Mexicans soft and sibilant hiss, the sound dripping of the tongue like silk sliding across velvet.

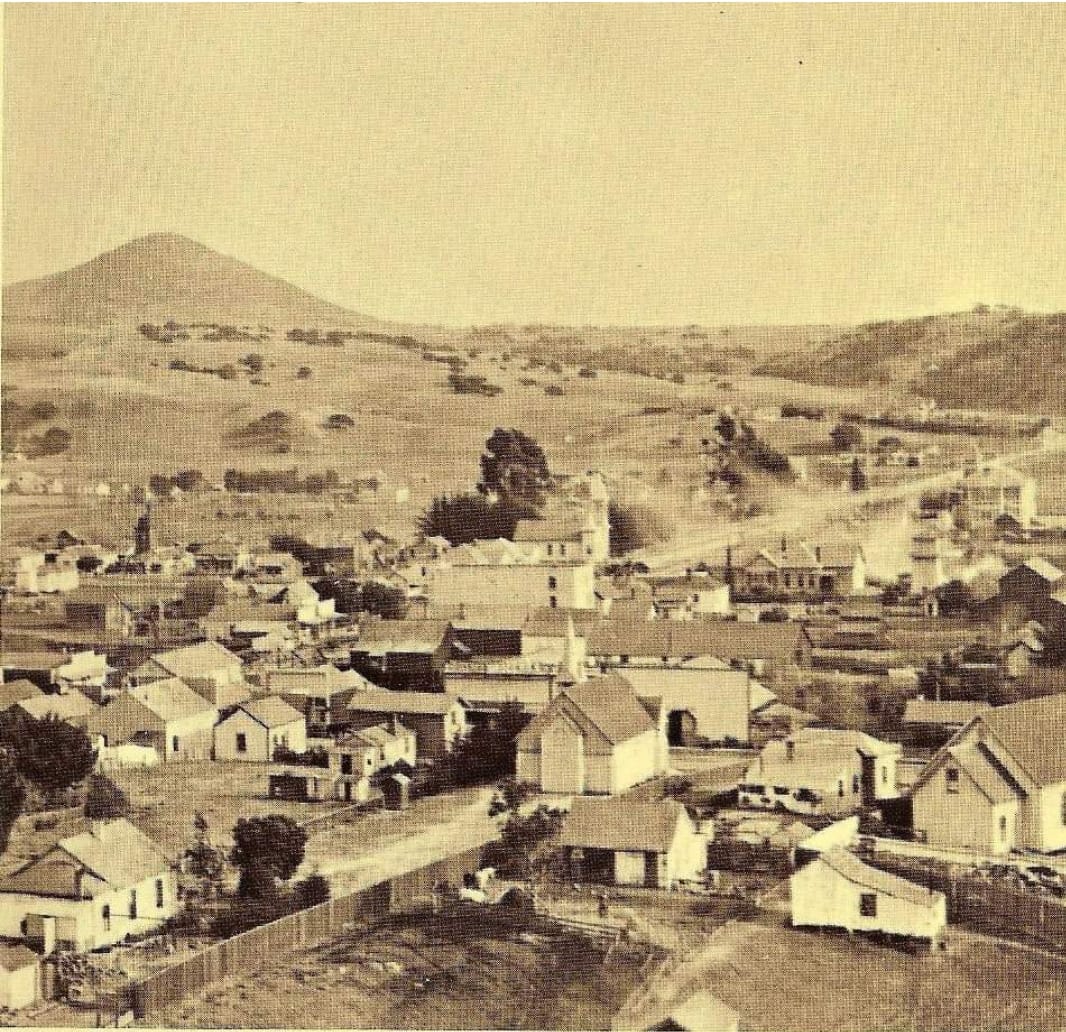

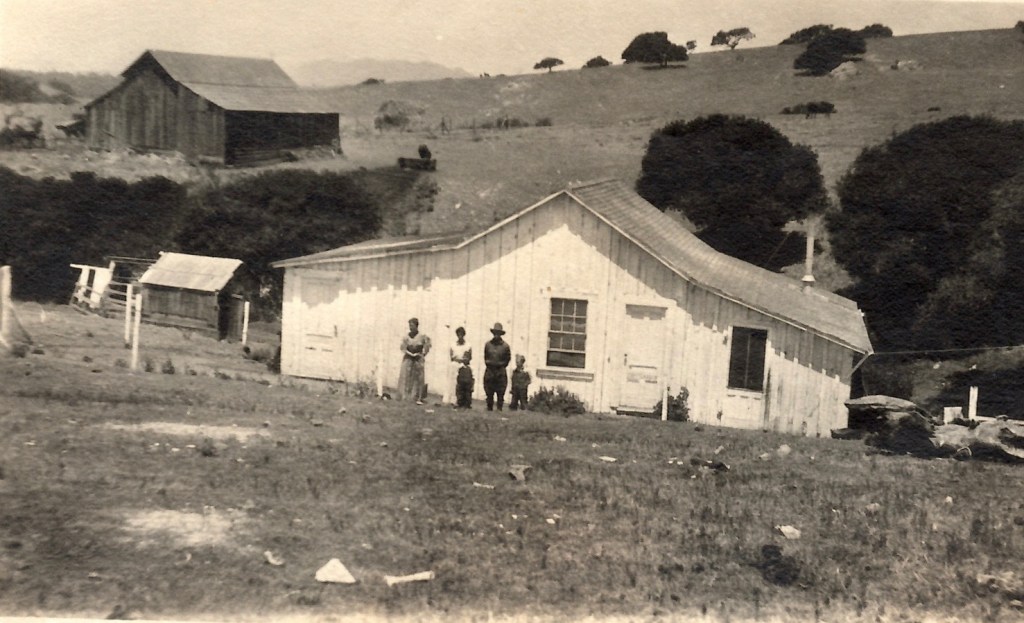

In 1955 the 110-block area on the north side of San Fernando Road was the dusty little town of Pacoima. It consisted of a smear of sagging, leaning shacks and outhouses framed by disintegrating fences and clutter of tin cans, old lumber, stripped automobiles, bottles, rusted water heaters and other garbage strung along the back alleys. In 1955 Pacoima had no curbs, cement sidewalks, or paved streets. Pacoima had dusty footpaths and rutted dirt roads that in seasonal rains become beds for angry streams. The 450 houses in Pacoima, with only 2,000 inhabitants, squatted in the clutches of blight and neglect. There, but not there.

First Nations people had lived in the flats below the San Bernardino mountains for thousands of years. The original name for the Native American village in this area was actually Pakoinga or Pakɨynga in Fernandeño, but since the “ng” sound did not exist in Spanish, the Spaniards mistook the sound as an “m” and recorded the name as Pacoima, as it is today. Natives subsistance farmed and ran sheep in the foothills and the little town began as a rancheria where Mission workers at the San Fernando mission lived after the missions were securlaized in 1826. For the next century and a half it had been home to the marginalized people who could live no where else.

The thing is, like many marginalized communities with strong ethnic ties there was a richness of culture running throughout those dusty muddy alleys. With little migration, families had forged ties with one another and created a patchwork of social order. Fiestas, Quinceaneras, saints days and weddings brought the extended families together. It was a small town where everyone knew each other. The watchful eyes of aunties and abuelas kept an eye on kids as the went about their kid business. At the time you had to get out of town to get in real trouble.

Richie’s mother Conception must have dandled his chubby little body on her knee, boosting him up and down, holding his little fingers as they listened to the music of the Pacoima Barrio. La Bamba came to him as an infant.

It came a long way. From the ancient sub-saharan kingdom of Kongo. Spanning central Africa below the Gulf of Guinea, the kingdom included some dependent kingdoms, such as Ndongo to the south. Trade with other African states was the main commercial activity in the centuries before the white invasions. Kongo was a wealthy and influential kingdom state based on its highly productive agriculture and the increasing exploitation of mineral wealth.

In 1482, Portuguese sailing ships commanded by Diogo Cão arrived off the coast of the Kongo. Cão landed an expedition which explored the extreme north-western coast of Ndongo in 1484. Other expeditions followed, and close relations were soon established between the King of Portugal and the Kingdom of Kongo. The Portuguese introduced firearms and many other technologies, as well as a new religion, Christianity; in return, the King of the Congo offered for sale, slaves, ivory, and minerals such as gold and silver. Slave trading was an ancient and accepted form of trade, predating written history and fully accepted as a way of doing business by both the Portuguese and the African nations of central Africa. The slaves themselves had no choice as to their fate.

Over the span of two centuries, Kongo was ruled by the Portuguese, Dutch, Brazil and then the Portuguese again. Each change of ownership was accompanied by savage warfare between the nations wishing to exploit the riches of Africa and the Africans themselves. Hundreds of thousands of prisoners were sold into slavery by all sides, the majority being shipped to the New World. Brazil at first, then to Dutch possessions all over the world. They were transported to the Caribbean and what was not yet the United States. The future United States was still made up of Spanish French and British colonies but in order to grow they were in need of vast numbers of laborers to exploit their new lands. It is estimated that beginning in 1619 more than ten million people from Africa were imported into north America and sold like property.

The slave trade was and horrible you must never make light of it, bound people to their owners for life to do whatever they pleased with a human being that was considered just property. Millions of African people died or were subjugated to the interests of the plantation owners in the western hemisphere, there is something entirely missed in the textbooks you read in school. To believe that they were somehow sub-human is to fly in the face of our common history. Slave uprisings were common and planters had every right to be terrified of them. A people who were subjected, denied the simple right to read and right, worship as they pleased, denied any memory of their African culture and in many cases forbidden the simple pleasure of song. This festered.

The descendants of generations of the MBamba people from Ndongo (Angola) who lived along the Bamba River and had been sold west to Brazil, Cuba, Jamaica and the other Caribbean islands were also sold into New Spain (Mexico) at Vera Cruz a century and a half before they reached the American colonies.

What they brought our modern culture they paid dearly for. We learn early on in school how Europe and Asia gave us important literature, science, and art. How their nations changed the course of history. But what about Africa? There are plenty of books that detail colonialism, corruption, famine, and war, but few that discuss the debt owed to African thinkers and innovators.

They MBamba didn’t come alone. There is nothing physical that you can hold in your hand, no baggage that came during those centuries of slavery. No slave Hell-Ship carried any luggage. Everything came in their heads. All the things that defined culture, speech, art, history and above all, music.

By the seventeenth century, the west African people had made it west to old Mexico. Hernán Cortés founded La Villa Rica de la Vera Cruz (“The Rich Town of the True Cross”) in 1519. As the chief seaport between colonial Mexico and Spain, Veracruz prospered as a port and became the most “Spanish” of Mexican cities. Because of its strategic location and direct overland connections to Puebla and Mexico City. it was attacked and captured many times by pirates. In the 16th century Francis Drake and other British pirates savagely attacked the city several times.

Just before dawn on May 18, 1683, pirates stormed the port city of Veracruz in the Viceroyalty of New Spain on the shores of the Gulf of Mexico, easily overwhelming its Spanish military defense. For two weeks, the buccaneers, led by the Dutch Captain Laurens de Graaf and several hundred French and English volunteers, wreaked havoc. They raped and looted, pillaged and murdered at will. The Pirates demanded steep ransoms for the release of their valuable hostages which included the governor of Vera Cruz.

But the ultimate crime is what they did in the end, They kidnapped almost the entire population of people of African descent, because slavery was rapidly expanding and the English and French colonies at this time and there was a a huge market for such captives. Human beings were worth more than gold and jewels.

Just before their departure on May 31, the pirates captured between 1,000 to 1,500 Veracruzanos and loaded them onto their fleet of 13 ships. Then they set sail for the pirate sanctuary of St. Domingue, todays Haiti. There, they sold their human cargo. The captives, people of African descent, many of whom had intermarried and intermixed with the Spanish and indigenous population, some already Veracruzanos in the second or third generation, were deemed mulatos, pardos, negros and morenos. Chattel slaves or not, the pirates loaded them up and sold them into slavery. New Orleans, Havana, Santo Domingo and Charleston South Carolina’s slave buyers were there with bags of coin. Slave markets in those places quickly sold them off. The seeds of Africa were scattered everywhere. The melting pot of musical style went with them spreading across the continent.

Soon after the slaves remaining in and around Vera Cruz organized a revolt called the Bombarria which, when put down scattered people even more. Each attack on Vera Cruz spread the slave population as they used the opportunity to run away, many headed north and west to live among Native Americans.

Again, without personal possessions they took only what they could remember. Their culture and their music. Especially the music which is always paramount in peoples who were illiterate. By the mid- nineteenth century this had become a mixture of Caribbean creole influences, Spanish Flamenco, Afro-American percussive and in the 19th century Celtic music from Brittany in France which was brought to Mexico by the French soldiers of the Emperor Maximillian.

Like a whirlpool pulling water down, mixing all these elements, hollers and chants from the cotton fields where enslaved people trudged, bent over, from dark to dark, native American drumming, the northern Mexican stomps and shakes, the Bombolear, danced at weddings and the percussive heel strikes of the Flamenco. Traditional La Bamba evolved along with Ragtime, Jass, (The original spelling,) and Rhythm and Blues. Throw in Gospel, Scots-Irish hill country music, Tex-Mex and Corridos, all of it played to a syncopated rhythm. Syncopation is the beat that still permeates much of the American music, a beat that comes from African slaves in the United States, Mexico, the Caribbean and central and south America. Syncopation is quite literally the rhythm of your heart.

“La Bamba” is believed to come specifically from that slave uprising in 1683. The song was traditionally performed at weddings, where attendees were encouraged to make up verses of their own. The traditional aspect of “La Bamba” lies in the tune, which remains almost the same through most versions. The name of the dance referenced within the song, which has no direct English translation, is presumably connected with the Spanish verb “bambolear”, meaning “to sway”, “to shake” or “to wobble”.

The music migrated to California. Some of the earliest histories of California have descriptions of fiestas, weddings and christening celebrations. Richard Henry Dana who wrote Two Years Before the Mast was a Harvard student from a wealthy shipping family who shipped as an ordinary seaman on a hide trading voyage to California and the west coast of America. His book paints a mainly unflattering picture of the people who lived here but in 1836 he and the crew of his Brig attended the wedding of Alfred Robinson, a gringo shipping agent and the daughter of Santa Barbara’s Principal citizen .The bride was the daughter of Jose Antonio de la Guerra y Noriega, one of the most prominent Californios in all of Alta California . Alfred Robinson and the beautiful Dona Anneta Ana Maria De La Guerra were wed in the old Santa Barbara Mission church.

Dana wrote: “The bride’s father’s house was the largest home in Santa Barbara, (It still stands) with a large court in front, upon which a tent was built, capable of containing several hundred people. As we drew near, we heard the accustomed sound of violins and guitars, and saw a great motion of the people within. Going in, we found nearly all the people of the town* – men, women, and children – collected and crowded together, barely leaving room for the dancers; for on these occasions no invitations are given, but everyone is expected to come, though there is always a private entertainment within the house for particular friends. The old women sat down in rows, clapping their hands to the music, and applauding the young ones. The music was lively, and among the tunes, we recognized several popular airs, which we, without doubt, would have taken from the Spanish Africans.”

A depiction of El Fandango a la Casa De la Guerra in 1836 is featured in one of the sprawling Santa Barbara scene paintings in the Santa Barbara County Courthouse.

Like all little children, Ritchie could dance before he could read or write. He was one of the fortunate few who knew what he was born to do. He was given a guitar when he was five years old and though left-handed, he taught himself to play with his right. He played completely by ear, copying the music he heard.

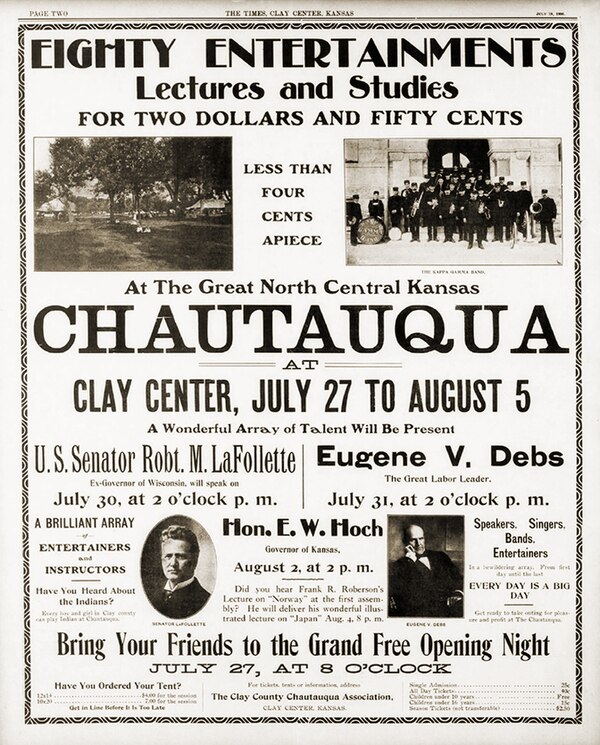

When he began playing at high school dances and parties he had a ready made audience impatiently waiting for the new music that always accompanies an emerging generation of young people. Their parents grew up on Glenn Miller and Artie Shaw or tunes from Tin Pan Alley. They went off the to war and dreamed the music while they waited to come home. Six Million men and women served in WWII, those that worked the defense plants, shipyards and aircraft factories got right down to business and produced the Baby Boomers. The Boomers, as they entered their teen years wanted little to do with their parents swing music, they wanted something to call their own. If it offended their parents that was all to the good. Elvis kicked down the door between “Race” music and the treacly harmonic clap-trap of street corner Philly and got their feet moving. Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee and Fats Domino came a running. Johnny B Goode, Bee Bop a Lula, there was suddenly a whole lotta shakin’ goin’ on Baby.

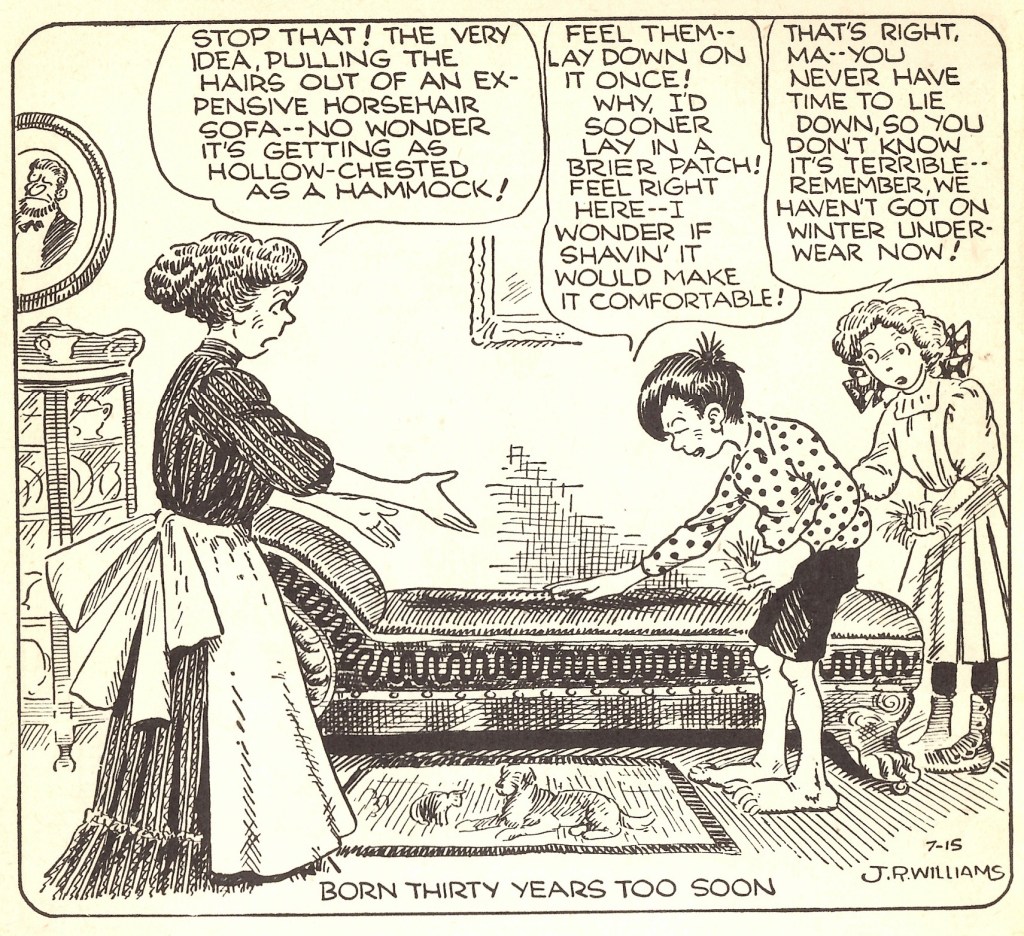

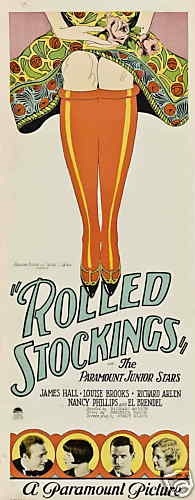

It wasn’t only music either. Clothing, food, social events were all busy rolling over. At the Pruess ReXall’s drugstore counter in our little town which had once catered to the high school crowd suddenly lost it’s appeal. Teens didn’t walk uptown to the fountain anymore. Now they had cars, they could go anywhere, and they did.

Bobby sox, loafers, ponytails tied up with ribbons gone with the snap of the fingers. Bobbie Chatterton had the last ponytail in my high school in 1958. Goodbye ankle length pencil skirts. So long the ducktail, the jelly roll and the spit curl. Hello the Pixie and lurking just over the horizon, Bouffant and the Flip.

The Lindy Hop, exit stage left. The Twist, enter right. Dance became free expression. “Bambolear”, “to sway”, “to shake” or “to wobble.” Just shake it up, Baby.**

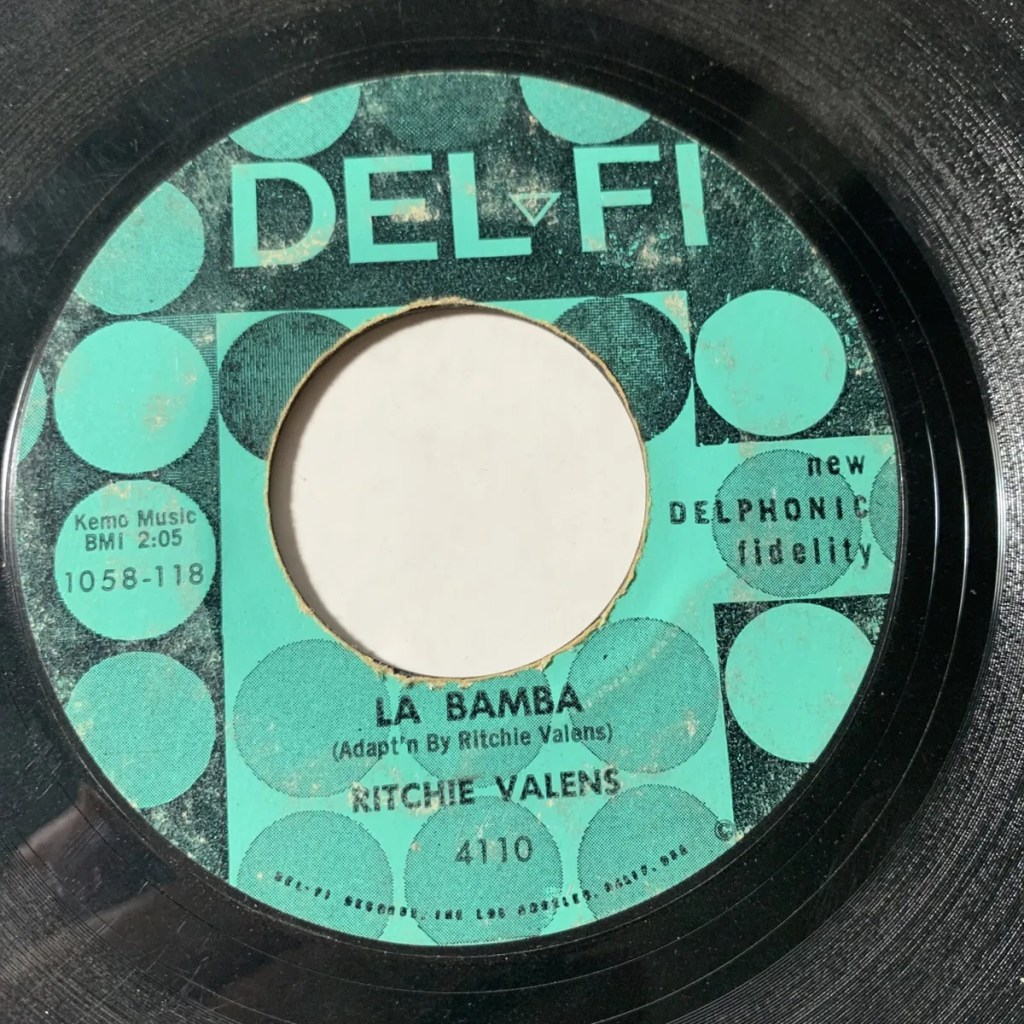

Suddenly A&R men were trolling clubs, high school dances, intermission shows at movie theaters and Juke joints looking for new talent. Bob Keane the owner, engineer and janitor of a tiny home based record label, Del-Fi records got a tip. He showed up at a Saturday afternoon matinee show in a theater in San Fernando, California. He stood in the back as a band called the Silouehettes dragged their equipment on stage, tuned and with a cue from the stocky kid with a Telecaster guitar, launched into a driving, beat driven version of the old tune. Spinning to face the audience, Richard Valenzuela, a grin like a garden gate in a white picket fence, obligatory rock and roll spit curl dangling and dancing across his forehead, jelly rolled duck tailed hair brought the audience screaming to its feet, girls jumping and ponytails swaying, and boys stomping their feet. Keane was floored.

Within a week Richard Valenzuela was in Keane’s basement studio in Silverlake, making a demo and the next week his little band of high school friends were forgotten forever,

The Silouehettes were replaced by the already famous “Wrecking Crew” of studio master musicians. Hal Blaine on traps, Carole Kaye backing up on Rhythm guitar, Earl Palmer, bass and René Hall, guitarist and arranger. They cut four songs that day at Gold Star Studios, “Come On, Let’s Go” and three others, all originals, all credited to Valens. His second record. “Donna” Written about a real girlfriend Donna Ludwig, a classic last dance tune heard in every high school gym in the country for years. The “B” side, “La Bamba”. It sold over one million copies, and was awarded a gold disc when a million records was really a million.

It was the late 1950s when a 16-year-old boy took an old Mexican folk song and set it to a rock ‘n’ roll beat. “La Bamba” made rock ‘n’ roll history when it became the first Latin-based song to cross over to the pop and rock audience. That teen-ager, Ritchie Valens, was made famous. it was the first Spanish song to reach No. 1 on the American charts, and the only non-English song to be included in Rolling Stones “500 Greatest Songs of All Time,” at #354, surely far to low but that’s museum politics.

People all over the world, when they think of U.S. culture, and they’re like, ‘Yeah, “La Bamba.” Yes it is, but it’s not simply American but African, Caribbean, All-Americas rolled into one. That’s dope. This song has survived slavery, colonialism and you’re darn sure it’s going to survive anything that comes along, because it lives within us. I invite everybody to also make it yours.

And those Branch school girls? They are pushing, well I shouldn’t say what age but at high school reunions they can still shake it like they did in 1959.

The video above is a more traditional take on La Bamba. Note the old style instruments which have been in use for centuries. If you love this old song there are literally hundreds of version on YouTube and other sharing sites. Try Los Lobos at Watsonville High School or “Playing for Change, La Bamba”

If you need any proof for the appeal of this song put your three year old granddaughter down and play it for her. Bambolear!

*If you are California, especially from the Cow Counties, every Ranchero who settled here shortly after the wedding was there at the fiesta including Captain William Dana of the Nipomo Rancho and Don Francisco Branch of the Santa Manuela.

**La Bamba still works. In a 1988 at a concert in Argentina, “The Boss” brought 70,000 Argentinians to their feet before he finished the first three notes of the song. 70,000 people swaying, dancing and singing along. The old song still excites.

Michael Shannon is a writer, he lives in Arroyo Grande California with his family. This for his musical sons