Written By Michael Shannon

Page One

Saturday, October 19, 2024

Dear Dona,

Something in your note about not knowing what your dad did in WWII struck a cord. I have some research from the Manzanar story so I though I’d look into your dads service in World War two.

Most people have very little or no knowledge of the Japanese Nisei experience. I’ve interviewed people of that generation who had no idea that there were Nisei soldiers at all. In fact, there were none in the Navy, Marines or Air Corps, only the Army and its nurse crops accepted Nisei and only citizens at that.

I’m sending you this to pass along what I found about your dad’s service. One of the complaints of military men is the constant record keeping they must do. The funny thing is that once they are separated from the service the records go who knows where. Perhaps they are stored in cardboard boxes at the back of the warehouse pictured in the first Indiana Jones movie. Who knows? In any case some can be found in order to fill in a family’s story. In a way its a treasure hunt. There can be quite unexpected results. In fact its like assembling a puzzle when some of the pieces are missing.

The difficulty for children is that wartime veterans are extremely hesitant to tell them what their experience was like. There are a few reasons why that is so. One, the kids have no background experience or education to make much sense of it. Two, in the case of combat veterans, the stories are too horrible to contemplate telling your own children. Third, their hope is, that surely the kids will never have to experience their fathers hell for themselves.

Most sons and daughters of veterans never hear much about the parent who actually served. In WWII, somewhere around 12% of all regular army soldiers saw combat in which their was actual shooting. The average combat soldier was involved in combat for a period of around forty days. By comparison soldiers in Viet Nam averaged 240 days and in Afghanistan close to 1,200 days. The difference wouldn’t matter to your father. One day at a time is how it’s done.

Your father saw active combat against the Japanese Imperial Army on the islands of Luzon in the Phillipines and went in on the first wave in the invasion of Okinawa. The battle for Okinawa drug out over nearly three months, from April 1st until June 22nd 1945.* Okinawa was the last major battle of World War II. It was the bloodiest battle in the Pacific War. It involved 1,300 U.S. ships and 50 British ships, four U.S. Army divisions, and two Marine Corps divisions. The U.S. objective was to secure Okinawa, which would remove the last barrier between U.S. forces and Imperial Japan. By the time Okinawa was secured by American forces on June 22, the United States had sustained over 49,000 casualties including more than 12,500 men killed or missing. The fighting was absolutely vicious with the Japanese fighting to the last man in most cases. The battle caused more than twice the number of American casualties than the Guadalcanal Campaign and Battle of Iwo Jima combined, with the Japanese kamikaze effort causing the American Navy to suffer more casualties than any previous engagement in the Atlantic or Pacific. The Navy suffered the greatest loss in its history.

The U.S. Navy lost 32 ships and aircraft, and 368 ships suffered damage during the Battle of Okinawa, . The U.S. Navy also lost 49,151 sailors, with 12,520 killed or missing. The Japanese by comparison lost more than 110,000 military personnel killed, and more than 7,000 were taken prisoner during the fighting.

The number of Japanese surrenders was unusual for the Pacific war. Most of the credit must go to the personnel of the Japanese American members of the Military Intelligence Language Service or MILS as it was known. Both your father and uncle were members and attended the Army’s Japanese language schools.

So how did he get there. The answer is multifaceted and complicated because as always anyone history when its being written is like a juggler trying to keep too many balls in the air..

When I was researching the series on Manzanar I used, as my primary sources two Japanese American archives which were put together after World War two and have grown year by year ever since. Collected were diaries, letters, newspapers and radio news, family photos and most fascinating; oral histories by a very wide cast of characters. Generals, politicians, researchers and thousand of ordinary citizens who lived through the concentration camps.

When I talked to people in that generation, many whom I knew personally, I learned that the community, the community of the same age, those in high school or younger who were coming of age in the late thirties lived quite a different life than many might imagine. What they though about one another was different than the preceding generation.

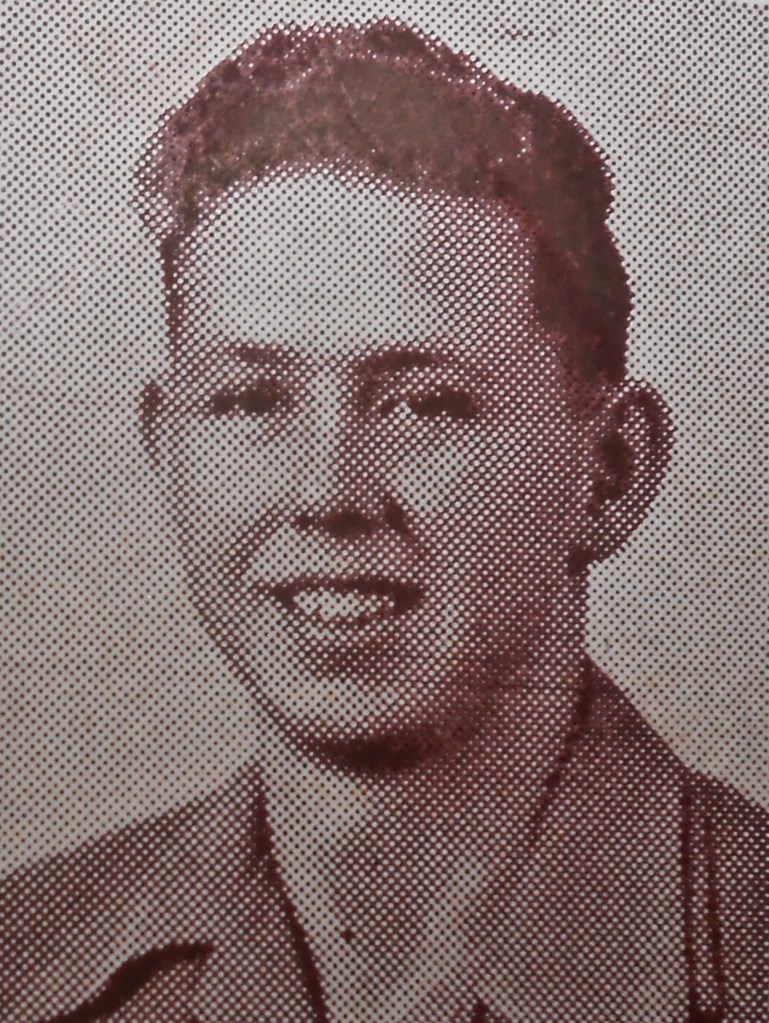

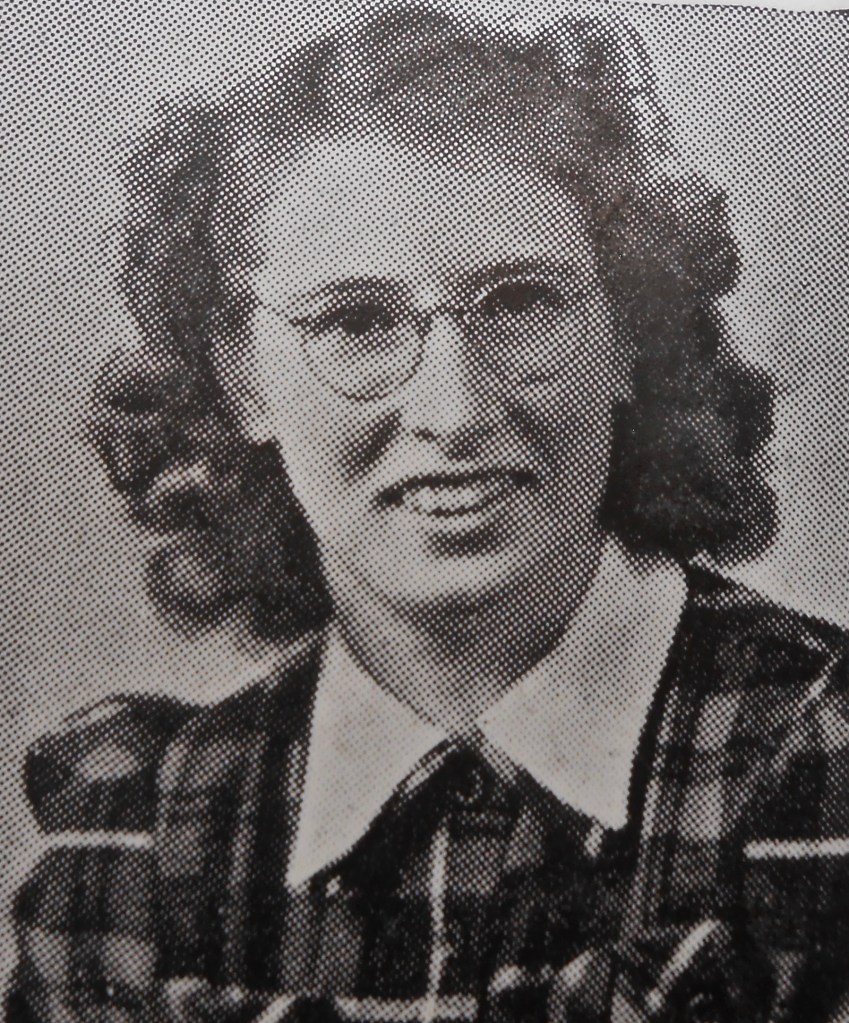

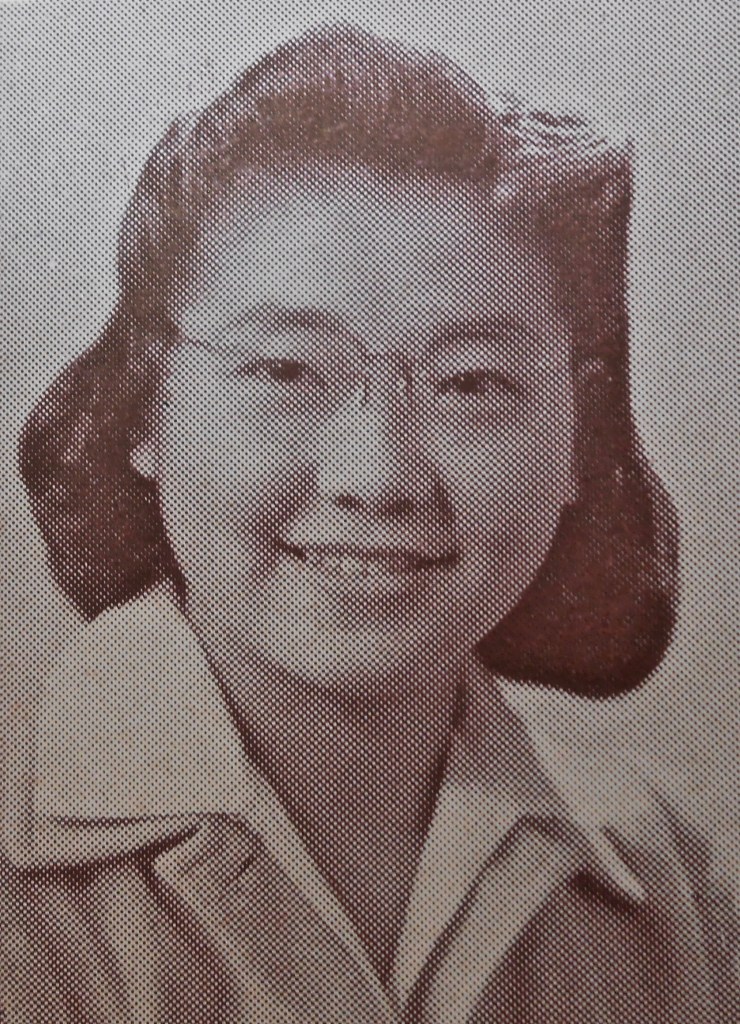

Looking through the old yearbooks from that time it’s easy to see Nisei kids were completely integrated into teenage life. Sports and clubs, social events all featured mixes of kids from all backgrounds.

My dad was a scoutmaster in the late thirties and kids like Haruo , Ben Dohi, John Loomis, Gorden Bennett and Don Gullickson along with my father told me funny stories about camping together and there wasn’t a hint of any racism. Stone went to HS with my father and was a life long friend. Personally, I don’t think it ever occurred to me that Leroy or Masaki was any different than I was.

Quite obviously there was discrimination by older folks and would be a great deal after Pearl Harbor but amongst those kids who who were in or just graduated in the years before the war there was little. Contemporary accounts in the local papers list Nisei kids names in all the kinds of chatty articles written about the goings on of youth. My fathers Boy Scouts listed the names of many Nisei kids and interviews with them showed me that they were friends no matter their skin. It strikes me that that generation saw little difference amongst themselves. They spoke the same high school language, they dressed alike as kids do, they combed their hair the same. Nisei boys played baseball, football and basketball together and as now, kids for the most part supported each other against the machinations of adults.

My own experience as a high school teacher illustrates my point. Adults, teachers and administration might publicly dislike your style of dress, or how you wear your hair but the kids themselves will put up a united front against any perceived transgression into the territory they reserve for themselves. You yourself will remember girls climbing the trees at school to protest the dress code. I’m sure ethnicity had nothing to do with that because kids unite over things they find unfair. Your dads friends would have felt the same.

A case in point, I never heard a disparaging remark from any adult I knew who went to school with your dad, uncle or any other Nisei because they knew who they were. They weren’t “Japs,” they were friends. That foul term was reserved for the Imperial Japanese, not friends.

When your father graduated from Arroyo Grande High School, the old brick one on Crown Hill in 1936 the Japanese Imperial army had invaded Manchuria and was moving into China, the Rape of Nanking was the next year. Mussolini, 1928 had annexed Libya and in just the year before your dad’s graduation had instigated the war in Ethiopia where he used poison gas, tanks and air power against tribal armies armed with old muskets and spears. Hitler had opened the first concentration camps in 1933, just one year after he was elected to office. In little Arroyo Grande all of this would have been news. Radios and newspapers published world news. Young men were not much concerned I’m sure about all of this conflict, it was worlds away from the lives of rural farmers. was the possibility of war. Arroyo Grande was far, far away from world events.

The next three years would mean a great deal to the lives of the young and as events were to prove, terrible things to the were coming to the 126,948 people of Japanese ancestry in the United States, 74% of whom lived in California.

Crown Hill High School, 1941

Your dad graduated Arroyo Grande HS with the class of 1936 and was working for your grandfather until late 1941 when he decided to follow your uncle Ben into the service. He was inducted on October 31st, 1941 just a little more than a month before the attack on Pearl Harbor. No one knew that was coming of course but by that time the German army along with their allies the Italians had overrun France, Holland, Belgium, and most of western Europe, They had occupied Norway and were advancing on Egypt in north Africa. Greece was under Nazi control and most of eastern Europe as well. German submarines were slaughtering ships transporting material to Britain in the north Atlantic. On the 2nd of October the German army launched operation Tornado which was a continuation of the previous years invasion of Russia.

In the far east the Imperial Japanese army had invaded and conquered Manchuria and was steamrolling across China. The general staff in Tokyo was in the final stages of planning for the surprise attacks that were to come at Pearl Harbor, the Phillipines and the rest of Southeast Asia.

No one in the United States could have possibly missed the threat to the country by these events. On October 17, 1941, the German U-boat U-568 torpedoed and damaged the destroyer USS Kearny off Iceland, killing 11 and injuring 22. The day your father raised his right hand in Los Angeles and swore to defend his country disaster struck in the early morning hours in the north Atlantic. While escorting convoy HX-156, the American destroyer U.S.S. Reuben James DD-245 was torpedoed and sunk with the loss of 115 of its 160 crewmen, including all the officers.

The draft had been instituted by congress in September of 1940. Called the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940, it required all men between the ages of 21 and 45 to register for the draft. This was the first peacetime draft in United States’ history. Those who were selected from the draft lottery were required to serve at least one year in the armed forces. Once the U.S. entered WWII, draft terms extended through the duration of the fighting.

Although the United States was not at war at the time, many people in the government and in the country believed that the United States would eventually be drawn into the wars that were being fought in Europe and East Asia. Isolationism, or the belief that American should do whatever it could to stay out of the war, was still very strong with almost half the Americans polled saying we should stay out. But with the fall of France to the Nazis in June 1940, Americans were growing uneasy about Great Britain’s ability to defeat Germany on its own. Our own military was woefully unprepared to fight a global war should it called upon to do so.

The first number drawn in the 1940 U.S. draft lottery was 158, which was announced by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on October 29, 1940. Your father along with your uncle must have thought that it was better to volunteer than wait. The thinking at the time was that it was better to have some choice in where and when you served than be at the mercy of a blind system of quotas.

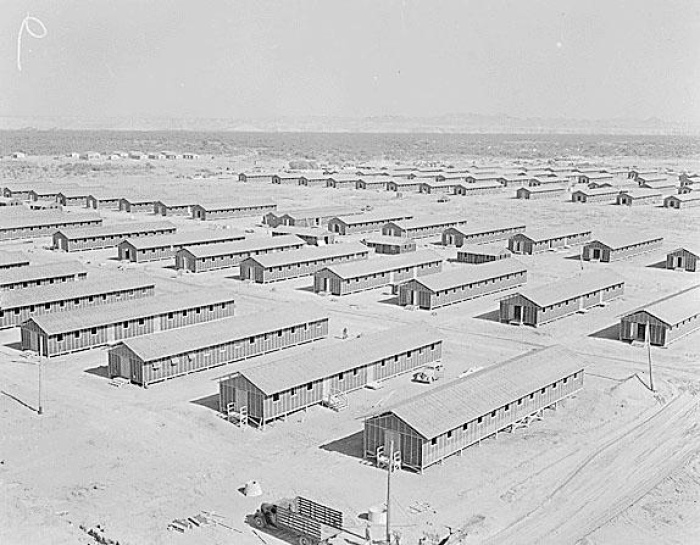

Hilo registered in Arroyo Grande on the 16th of October 1940. He may have waited to be called up because of your grandparents. Under the exclusion act they were not allowed to own land or a home and so like most Isei, rented. The land below the Roosevelt highway in the Cienega where they farmed and lived was rented. For tax and census reasons your uncle Ben was listed as the head of the family though he was just 24. I’m sure that was all just on paper though. Your grandfather certainly ran the show since with only your aunts left at home he was able to continue farming for the next five months until they were hauled off to Tulare and then to Poston, Arizona on the Gila River, the concentration camp where they and your aunts remained until 1945

the Poston concentration camp, Gila River, Arizona where most of the Arroyo Grande citizens where held.

Your father reported for active duty in Los Angeles on the 23rd of December 1941. There he took the oath to defend the constitution of the United States from all enemies foreign and domestic. Five months later his family was locked up behind barbed wire and held inside by soldiers armed with rifles and machine guns.

Name Hiroaki

Race Japanese

Marital Status Single, without dependents (Single)

Rank Private

Birth Year 1917

Nativity State or Country California

Citizenship Citizen

Residence California

Education 4 years of high school

Civil Occupation Farm hands, general farms

Enlistment Date 23 Oct 1941

Enlistment Place Los Angeles, California

Service Number 39167146

Nisei men reporting for Army induction, 1410 East 16th Street Los Angeles, CA, 1941

Page Two

Coming on October 26th, 2024

It’s pretty easy to form a picture of your great grandparents taking your dad to the old Greyhound bus depot at Mutt Anderson’s cafe, his parents wearing their best clothes as they did for important occasions. In 1941 they would have both been wearing hats, he in his Fedora and she with her go to church best, purse on her arm and those sensible heels women wore then. The family scene is always the same, father looking prideful and the mother just on the edge of tears but holding it all in so as not to embarrass. Hilo would have walked up the steps into the bus and found a seat, maybe at the window so he could look out and see mom and dad. All of them giving a subdued, shy wave as your grandparents hearts broke. Perhaps your mother was there too. My guess is she was………..

- I was born on the day Okinawa was invaded.

- The cover photo, The Brothers taken in 1945.

The writer is a lifetime resident of Arroyo Grande California and writes so his children will know the place they grew up in.