Page Three

Written by Michael Shannon

A Hobson’s choice is a free choice in which only one thing is actually offered. The term is often used to describe an illusion that choices are available. That’s the military to a “T”

December 3rd, 1942.

At morning roll call, the Lieutenant called your father’s name. He was told to report to headquarters right after morning chow. Like any good soldier he asked what was up and like any good officer the Lieutenant wouldn’t tell him. So after breakfast he hustled over to the headquarters building and reported to the Top Kick, the first sergeant. Hilo would have entered the office, stood on the yellow footprints painted on the floor and announced himself. The sergeant merely looked up then rummaged on his desk until he found what he wanted, then said simply, “Your Orders.” “Where to Sarge?” “Camp Savage, you’d better pack your winter uniforms,” and he laughed.

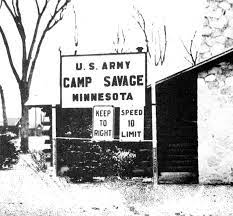

Camp Savage, Minnesota home of the Military Intelligence Service Language School. Camp Savage was a World War II Japanese language school located in Savage, Minnesota, and was the training ground for many Japanese Americans who served in the U.S. military. The buildings were originally built during the Great Depression to house Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) workers. In the rush to build up American forces the CCC tarpaper huts were put into service for the Nisei students. Part of Fort Snelling near Minneapolis, Savage was the new home of the language school. Originally located at the Presidio in San Francisco it was moved to the center of the country for the “safety” of the Nisei students. Californias attorney general Earl Warren a supporter of Executive Order 9066 signed by President Roosevelt on February 19, 1942: this order authorized the forced removal of all persons deemed a threat to national security from the West Coast to “relocation centers” further inland – resulting in the incarceration of Japanese Americans. You will note that the order only mentions “persons,” and not Japanese Americans, though the only removals just happened to be in the west. Germans and Italians weren’t moved anywhere.

Fort Snelling/Savage had a long history controversial acts by the US Government. Snelling is a former military fortification on the bluffs overlooking the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers. The military site was initially named Fort Saint Anthony, but it was renamed Fort Snelling once its construction was completed in 1825.

Before the American Civil War, the U.S. Army supported slavery at the fort by allowing its soldiers to bring their personal slaves. These included African Americans Dred Scott and Harriet Robinson Scott, who lived at the fort in the 1830s. In the 1840s, the Scotts sued for their freedom, arguing that having lived in “free territory” made them free, leading to the landmark United States Supreme Court case Dred Scott v. Sandford. In this ruling, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that enslaved people were not citizens of the United States and, therefore, could not expect any protection from the federal government or the courts. The opinion also stated that Congress had no authority to ban slavery from a Federal territory. United States Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger B. Taney ruled that African Americans were not and could not be citizens. Taney wrote that the Founders’ words in the Declaration of Independence, “all men were created equal,” were never intended to apply to enslaved blacks, they not being “Men” under the laws of the United States.The decision of Scott v. Sandford is considered by many legal scholars to be the worst ever rendered by the Supreme Court. The ruling was overturned by the 13th and 14th amendments to the Constitution, which abolished slavery and declared all persons born in the United States to be citizens of the United States.

The fort served as the primary center for U.S. government forces during the Dakota War of 1862. It also was the site of the concentration camp where eastern Dakota and Ojibway tribes awaited riverboat transport in their forced removal from Minnesota to the Missouri River and then to Crow Creek by the Great Sioux Reservation.

Hilo went down to the transportation office to find out how he would get up to Minnesota, it was nearly 1,400 miles away and when he checked the newspaper in the PX he found out that the high temperature that day was 21 degrees and the low was -1. Not the temperate central California weather where he was from nor even Fort Bliss where it was 68. He reckoned the crack about winter uniforms was good advice. Of course, being the army they weren’t going to issue him any either. He figured he would have to wait until Minnesota.

In ’42, getting from Texas to Minnesota wasn’t easy. The Army would waste no effort in flying a lowly private anywhere, going by car was impossible for those who had them and even if they could get rationed gasoline, that was impossible for an enlisted man. The Army sent soldiers by bus here and there but getting a chit to travel that way was forbidden to the Nisei. With the war in the Pacific the military considered it too dangerous for Japanese Americans travel alone or by private transport. He went by passenger train. Switching railroads and constantly being sidetracked by military trains which had priority, the 1,400 mile trip took six days. He had to sleep on the train car’s benches and jump off at the stations where the train stopped to buy something to eat. Even for a 23 year old in the prime of life it was an exhausting trip although considering what was to come, it was a walk in the park.

He and the other boys kept up on the war news by reading newspapers to pass the time. While they were enroute, the US Navy lost the heavy cruiser USS Northhampton in the Battle of Tassafaronga in the Solomon Islands, sunk by Japanese Imperial Naval torpedos. They read that the Afrika Corps was being pushed into a corner in Tunisia by the Allied armies and their surrender was expected, though that wouldn’t be soon. While traveling to Camp Shelby they read that the US Marines had turned over the mission in Guadalcanal to the US Army which immediately was involved in very heavy fighting in the interior of the island. American and Australian troops finally pushed the Japanese out of Buna, New Guinea. New Guinea was a place Hilo would soon enough become familiar with. Unbeknownst to the travelers, below the bleachers of Stagg Field at the University of Chicago, a team led by Enrico Fermi initiates the first nuclear chain reaction. A coded message, “The Italian navigator has landed in the new world” is sent to President Roosevelt. The result would, in the end, save the lives many Mils soldiers, but that would come much later, too late for many.

Following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, anti-Japanese sentiment and political expediency pushed President Franklin D. Roosevelt to order the army to set up Japanese internment camps in seven western states, that included Japanese Americans who volunteered at the U.S. Military Intelligence Service Language School in San Francisco. The school and volunteers had to move from the so-called “exclusion zone.”

All the western states but Colorado and Minnesota refused to host the school except Minnesota Gov. Harold Stassen who offered 132 acres of land in Savage to host the school. In 1942, Camp Savage was established. An old CCC camp and host to the Boy Scouts, it was run down and primitive. What buildings were still standing were augmented with the building of the cheapest of the military’s building, the loathed and ubiquitous tarpaper shack, the miserable hutment.

Hilo stepped down from the camp bus which had picked up the volunteers at the railroad station. He tossed his barracks bag up onto his shoulder and followed a Corporal who had been sent to get the. When they got to the headquarters building he turned, looked them up and down and over a big grin said, “you’ll be sorry,” followed by a laughter. Names Kobayashi,” he said, “Larry.” “Get checked in and I’ll take you to your quarters.”

Most of the men experienced for the first time the bitterly cold winter of Minnesota. Nearly all the students were from the temperate zones of the west. Some of the men suffered frostbites and persistent colds. The only source of warmth was the pot-bellied coal burning stove found in the classrooms and in the barracks. The stoves in the classrooms were kept burning by the school staff but the ones in the barracks were the responsibility of the students. If you had been designated barracks leader you usually had to wake up early at 4:30 am. to stoke up the stoves so that the rest of the men could rise and shine in a warmish barracks.

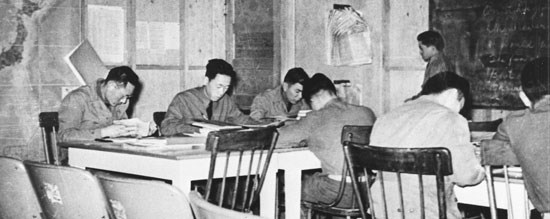

Classmates at Camp Savage. The Military Intelligence Service Language School, 1943. Densho Archive

The purpose of the school was for the volunteers to teach the Japanese language to military personnel. This skill could then be used to interrogate prisoners of war, translate captured documents and aid in the American war effort. A total of 6,000 students graduated from the school before it was moved to Fort Snelling in 1944.

The ancient Chines General Sun Tzu and philospher revered as one of the greatest military strategists, advised in his treatise that intelligence, procured from the enemy is the way to victory. George Washington set up an extensive intelligence system and it really hit it’s stride in the Civil War. Of the two types of intelligence strategic or long term planning and Tactical which concerns the enemy’s strength and location and is used to make immediate decisions on the actual battlefield.

The short but extremely intensive course was designed to meet the demands for linguists from field commanders in the Pacific. The studies included the study or review of the Japanese language, order of battle of the Japanese military forces, prisoner of war interrogation, radio intercept and many other subjects that could be of value in the field. Just to illustrate how intense our course was the kanji (ideographs) instructor would make us memorize seventy five characters a day just to make sure we remembered fifty for the next day’s test. Many of us studied using flashlights under our blankets after lights out at 2200 hours. Saturday mornings were devoted to examinations. Many woke up early, about 0400 hours, went to the latrine, sat on the commodes and studied for the tests under the meager lighting. The competition was so keen in class that the class grade average was in the mid-nineties.

The study week, Mondays through Fridays, consisted of classes from 8 to 12, a brief lunch break, classes from 1 to 5, a break for supper and compulsory supervised study from 7 to 9. Examinations were conducted on Saturday mornings. The soldiers were free from Saturday afternoon until Monday morning. The majority would hurry to the Twin Cities for Chinese food and movies. On Sundays most attended church services in St. Paul, where many students were befriended by a Mrs. Florence Glessner, who graciously invited the Nisei kids to luncheons and parties. Mrs. Glessner was a Red Cross volunteer and after graduation and assignment to the Infantry Divisions on Bougainville, the MIS soldiers made a collection from the members of the language detachments and sent the donation to the Red Cross through Mrs. Glessner. She later sent us a clipping from a Minneapolis newspaper about the donation “from her boys”.

Minnesotans rarely saw any Japanese-Americans and for the most part had little or no racial bias. Unlike the west coast where business and individuals were stripping evacuees of their property, houses, fishing boats and anything they could get their hands on the people of Minneapolis were giving dances and dinners to the kids at school. Showing an appreciation for the Nisei soldiers who were serving their country. Many students at the MISLS were astounded by this. Captain Kai Rasmussen, the camp’s first commanding officer was quoted as saying, “Minnesota was the perfect place because not only did the state have room for the school, but Minnesotans had room in their hearts for the boys.”

Your dad arrived at Savage after your grandparents had already arrived at Poston. It was very hard for them to communicate by mail. Nisei soldiers could not safely write in Japanese and in many cases the parents could not write in English. Letter were very carefully written, in your dads case probably by your aunts, He must have been worried sick about them and they him. They may not have even known where he was. If he got leave at the end of his class he would not even have been able to visit because in 1942, no Nisei soldier would have been allowed in the exclusion zone. When the restriction was lifted in 1944, he had already left for the Pacific war zone.

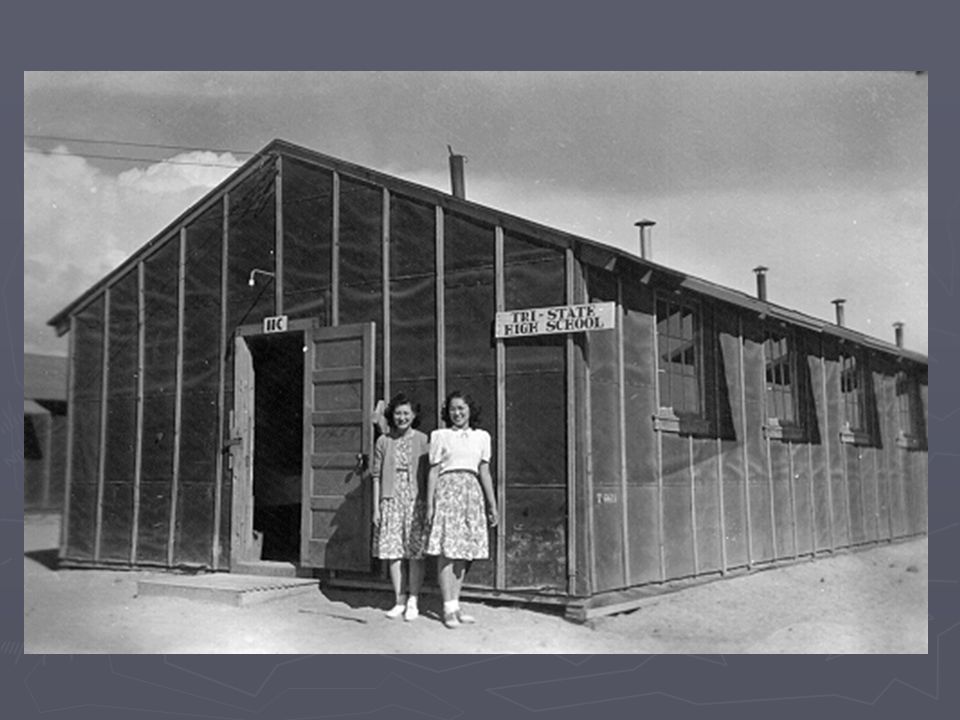

Tri-State High School, Poston Camp. 1943. Densho Archive.

The photo above is a sad commentary, but the two young ladies are a lesson in the girls resilient nature. Though held against their will behind razor wire they still managed to dress in the current fashion of young women. They wear saddle shoes, bobby sox, full knee length skirts, peter pan collars and sweaters, they would not be out of place in any high school in the nation. My mother dressed just like this. She was the same age

It was a rough go for them because almost al the students were from the exclusion zone and many had no idea where their families were. Lieutenant Paul Rusch, one of the senior instructors had spent decades in Japan as a Methodist missionary and knew the culture better than any other instructor. He lent a sympathetic ear. Students said they ween’t angry with the Army but that they were, “Just against everything that was happening with their families. We’re being treated as second class citizens and we hate it.” Imagine what it be like to be forced from your schools and home and cast adrift in a forbidding and alien place where only the most rudimentary life is possible. It was like life on another planet.

A widowed mother with six children in a strawberry field near Fresno. Two of her sons served in Italy and France with the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. She spent the war with her other four children in the Manzanar concentration camp in the Owens Valley of California.

Dear Dona page four

Coming November 8th, 2024

Unlike the American military where mail was censored and journals and diaries forbidden the Japanese Imperial Army thought the differences in language would make ordinary Japanese as indecipherable as any code to an American reader. The head instructors also knew that Japanese soldiers were brutalized by their superiors and would likely be resistant to the treatment the British were using on captured Afrika Corps German troops where violence and intimidation were routinely used. As many of the instructors had lived in Japan for extended periods of time they knew the Japanese were generally very kind and the spirit of co-operation was instilled in them from birth. The culture of Japan was bound to duty to the Emperor and higher authority. They believed that force would not be enough to get prisoners to break down……

Links to other chapters in the series.

Page one: https://wordpress.com/post/atthetable2015.com/12268

Page two: https://wordpress.com/post/atthetable2015.com/12861

Michael Shannon is a writer living in the Central Coast of California. He went to school with many survivors of the camps in his little farming community.