The End of a Hard Row.

By Michael Shannon

A hard row, something a farmer knows all too well.

As early as 1943, morale amongst the Japanese soldiers was very poor. The information compiled by the MIS translators wasn’t just about the killing of Admiral Yamamoto or Plan Z or the other logistical and strategic finds. US Army G-2 intelligence reported on the mindset of the ordinary Japanese soldier as seen through his own eyes in captured letters and journals.

One that can be easily manipulated politically. The difference for those being on the ground dealing with face to face combat or interrogation when captured left little to interpretation.

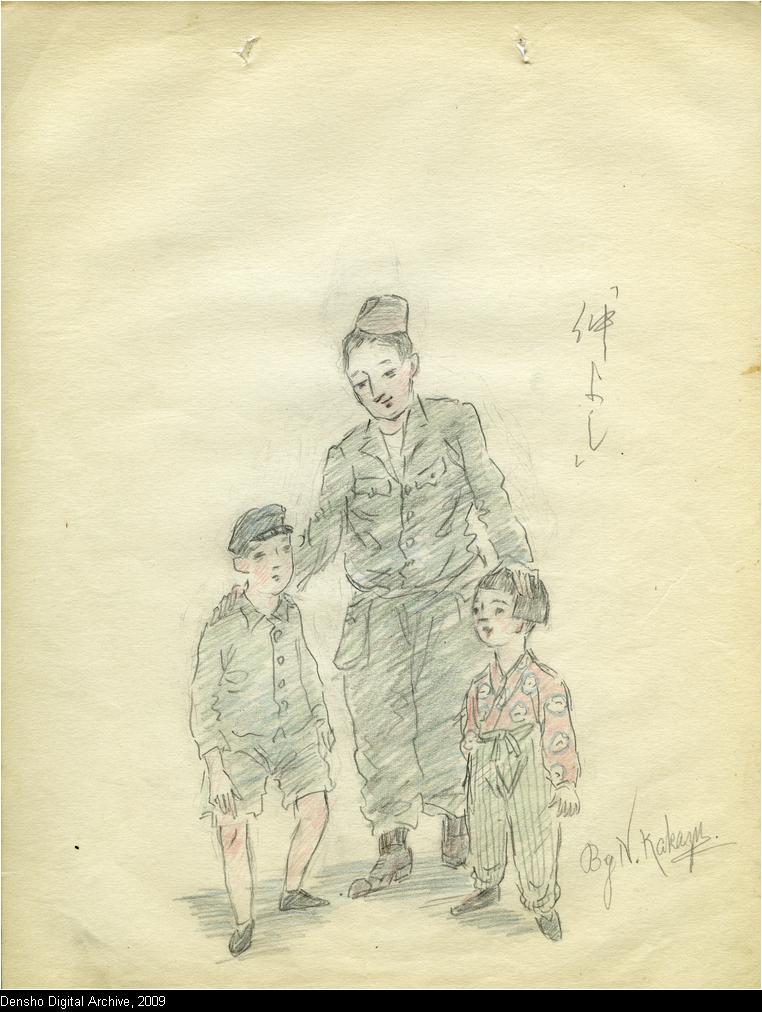

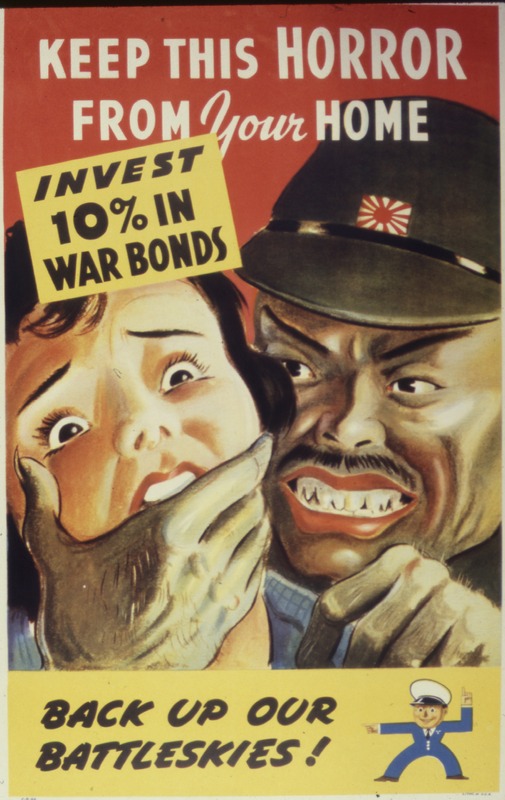

Many in the US believed the Japanese soldier was a fanatic, freely willing to give his life for the Emperor. The banzai charges. The kamikaze attacks. Individual soldiers throwing themselves under tanks with an explosive charge strapped onto their backs in a suicide attacks was the image the wartime press pushed. The truth of the matter is Japanese soldiers were farm boys, city boys, Just like our boys, they were drafted. Instead of dying in “banzai attacks”, these “fanatical” Japanese soldiers wanted to go home just like ours did. They couldn’t for fear of reprisal against their families by their own government. It must have been ironic to read of that treatment by the Nisei whose own families were behind barbed wire in concentration camps.

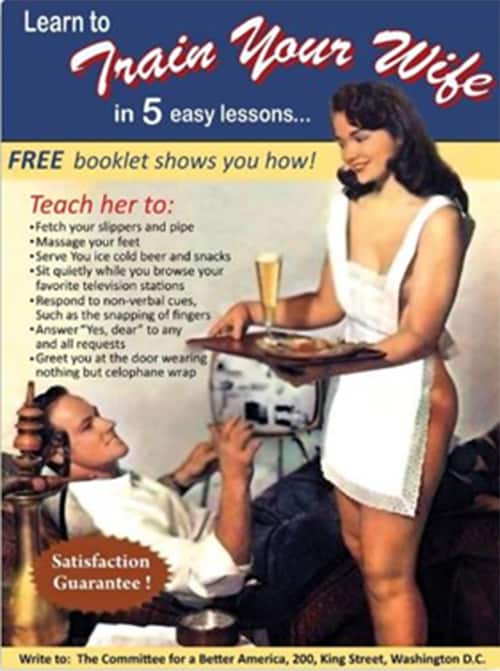

Neither side was immune from publishing the most scurrilous propaganda.

Being a buck private in the Japanese army made you a fanatic. In the American army you got the Congressional Medal of Honor. To a soldier of any army the end was the same. Media makes it seem that heroism is a choice but that is rarely so. Desperation or fatalism is much more likely.

General MacArthur told General Eichelberger, his chief of staff after the initial disastrous American showing by the 32nd division Buna-Gona, New Guinea, “I’m putting you in command at Buna. Relieve Harding. I am sending you in and I want you to remove any officer who won’t fight. Relieve regimental and battalion commanders; if necessary, put sergeants in charge of battalions and corporals in charge of companies, anyone who will fight, put ’em in.

MacArthur then strode down the breezy veranda again and turned back to Eichelberger . He said he had reports that American soldiers were throwing away their weapons and running from the enemy. Then he stopped short and spoke again, with emphasis. He wanted no misunderstandings about the assignment.

“Bob,” he said, “I want you to take Buna, or not come back alive.” Bob Eichelberger put on his three stars and walked into the front lines where the Japanese snipers could see him. Warned that he might be killed, he said, “I want my men to see a general in the line not in the rear. The word spread quickly through the Red Arrows troops and they turned the tide of the battle. That’s courage and the boys he commanded knew it when they saw it.

Eichelberger was recommended for the Congressional Medal of Honor, MacArthur disapproved it and awarded the Distinguished Service Cross to his staff officers at headquarters who saw no service. That was MacArthur at his political and selfish best. Eichelberger said nothing.

Major General Bob Eichlberger in New Guinea, 1943. US Photo

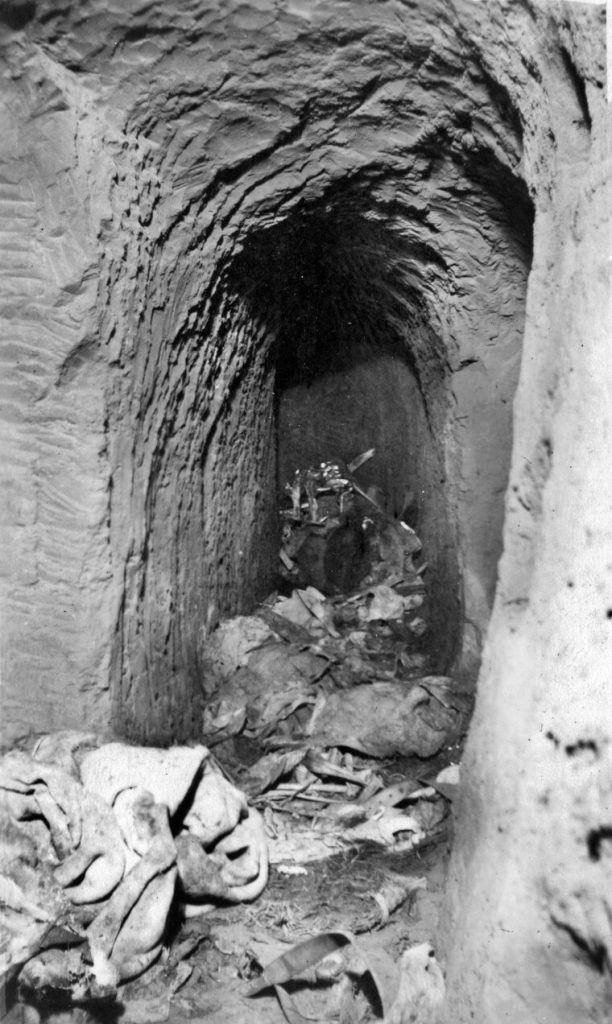

The MIS Nisei, as early as 1943 published a report detailing moral problems within the Imperial army. Culled from captured material, the official document spelled out problems within the Japanese officer corps. There were incidents of desertion, dereliction of duty, black market racketeering and hoarding rations for their own us. Enlisted men were homesick and felt helpless in the face of the war. Poorly led and often wasted in senseless attacks they were certainly as brave as American boys and throughout the Pacific campaign most American soldiers came to recognized this. Those Nisei who worked as cave flushers realized that the sense of hopelessness of soldiers hiding in caves during furious and savage battles were not always willing to die for the Emperor or their officers but could be talked into surrender by calm and kind words in their own language spoken by someone who knew their culture and in many cases who had been educated in their home prefecture.

Abandoned cave. USMC photo

Many of the MIS boys were descendants of families who emigrated from the southwest portions of Japan which were primarily rural. They came as contract laborers to work in the pineapple and cane fields of Hawaii and the fishing and agricultural areas of California. Hiroshima, Kumamoto, Okayama and Yamaguchi was where the majority of emigrants came from. By coincidence many of the Japanese troops in the southwest Pacific came from the same areas. The Kibei, American citizens who had been educated in Japan might, by a good chance be familiar with the home areas of the captured. The offer of a cigarette and comforting words from someone who not only spoke your language but in your own dialect quickly overcame any reluctance to speak. In many documented case the MIS translators personally knew schools, relatives, teachers, family members and in more than one case interrogated brothers, cousins and uncles. There is an instance where a cave flusher on Okinawa encountered his older brother inside.

The interlocking cave defense pioneered on Peleliu which brutalized the Army and Marines was quickly adopted by other Japanese units and even though you might not expect to see it used on the large islands in the Phillipines, it was. Your dad was still on staff with the Eleventh Army on October 20th, 1944 when the Philippine island of Leyte was invaded, the first step in the conquest of the Philippines by American, Australian, Mexican* and Filipino guerrilla forces under the command of MacArthur. The U.S. fought Japanese Army forces led by General Tomoyuki Yamashita. The battle took place from 20 October to 31 December 1944 and launched the Philippines campaign of 1944–45, the goal of which was to recapture and liberate the entire Philippine Archipelago and to end almost three years of Japanese occupation.

The invasion was a surprise because the Japanese assumed the Americans would invade Luzon first so many troops had been withdrawn from Leyte and those left had been pulled back from the prepared beach defenses. Fortunately for our troops, the Japanese General had withdrawn his troops from shoreline defensive posts. Even though there had been up to four hours of bombardment by the USN of the shore defenses, many fortifications – including pillboxes – were untouched. General Kenney concluded there would have been a blood bath similar to Tarawa if the Japanese hadn’t withdrawn.

The advance was so rapid that that MacArthur made his walk onto the Leyte beach a “Hollywood-esque” event on the first day. He actually had several takes done of wading ashore being the media seeker he was but. Being on MacArthurs personal MIS staff, you father may have been there though I could find no evidence of that. Soldiers in the know laughed at MacArthurs self promotion remembering him as “Dugout Doug” from Bataan and Corregidor in 1942. A foot soldier has a quite different view of rear echelon soldiers no matter how important he thinks he is. Patton’s well known nickname “Old Blood and Guts,” was easily changed to. “Yeah, his guts, our blood” by the infantry soldiers of his third army in Europe. Like a politician, which he was, the entire landing was a production. He had Manuel Quezon, the president of the Phillipines, several Philippine Scouts of the Filipino army, his staff officers each in his crushed hat echoing their bosses famous hat with the tarnished “Scrambled Eggs” and all wet to the knees. No one though to wear combat boots though and their dress brown shoes indicates they didn’t expect to even get wet. MacArthur was furious at the cox’n of the Higgins boat he landed from and wanted him punished until he saw the photos and decided he looked sufficiently heroic. The Cox’n was spared.

“I Have Returned.” Carefully posed and including representatives of the Filipino Army, the Army Air Corps and various staff officers MacArthur wades in for the third take. Check out the bemused expression on the face of the soldier just to MacArthurs right, above the little Filipino Major.*

“People of the Philippines: I have returned. By the grace of Almighty God our forces stand again on Philippine soil—soil consecrated in the blood of our two peoples. We have come dedicated and committed to the task of destroying every vestige of enemy control over your daily lives, and of restoring upon a foundation of indestructible strength, the liberties of your people.” MacArthur.

The landing on Leyte looked good on newsreel, there were even a few gunshots in the distance but the landing was safe enough for the men from the rear. Distant gunshots were exhilarating and added a little flavor to the event. The rest of the entire Philippine campaign would be bitter, savage and cost the United States military dearly. The Phillipines were not secured until the end of the war in August 1945. The Allies totaled up 220,000+ wounded and dead before it was over. The Japanese Imperial Army lost over 430,000.

Luzon was mostly jungle fighting but Leyte with the nations capital city of Manila turned out to be some of the worst urban warfare of the entire war. The Japanese were in desperate straits. The army and air force could not be reliably reinforced because the surface navy now controlled the air and US submarines controlled the inland sea and had devastated the Japanese surface fleet, particularly supply ships that soldiers on the islands were nearly cut-off from Japan.

Because of the MIS translators the Americans brass knew this. They knew where the ammunition dumps were, food supplies, location of all Japanese headquarters and many troop movements. At sea, the Navy was informed of Japanese Naval plans and was able to prepare for what became “The Great Marianas Turkey Shoot” when Naval aviators decimated the air fleets of the Japanese Navy and Army in the Battle of the Philippine Sea, downing 65 planes and sinking one of Japan’s last carriers. Fighting on the defensive with no air support the isolated Japanese troops on the islands became more desperate and fatalistic.

No one knew of course but the war had less than a year to go but the nature of war in the Pacific saw the fighting get more and more desperate and dangerous. There was literally no hope for the Japanese and they knew it.

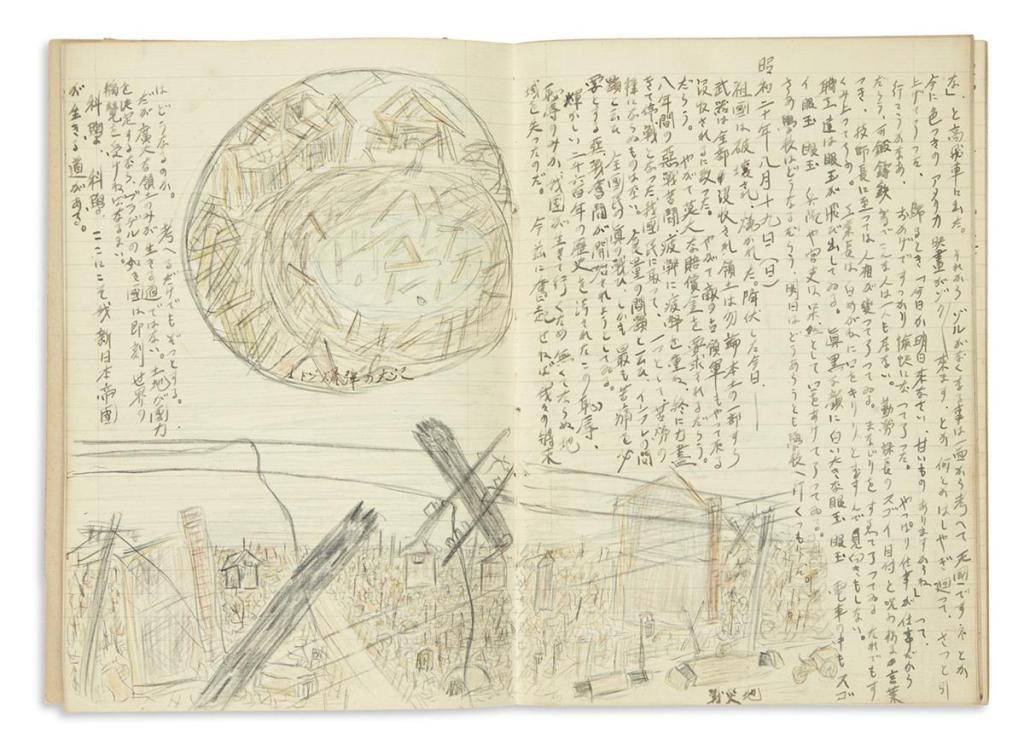

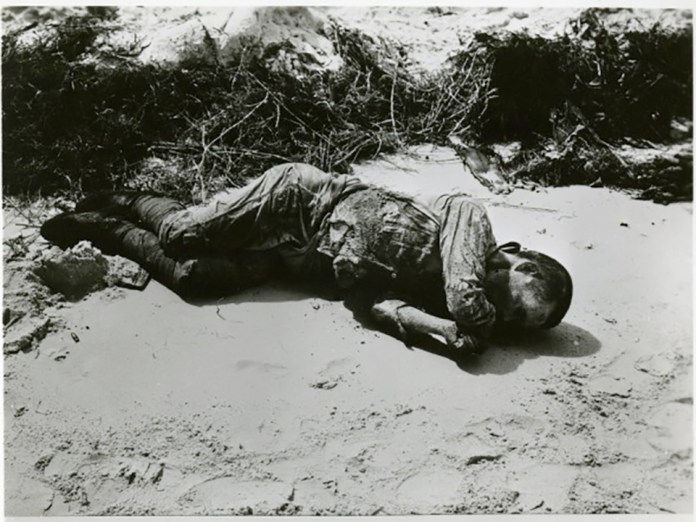

Lance Corporal Kiyoshi Koto was starving and wounded, but it is unlikely that he was troubled by his hunger or his pain as he reached the front on the day he had written his letter. Koto was killed in action about midnight on the same day, and his letter was never delivered. Instead, an American soldier pulled the letter from Koto’s uniform pocket and took it to his Nisei MIS intelligence section. The letter was translated into English while a few of Koto’s captured countrymen dug a grave for him somewhere on the site of the battle. The short paragraphs that Koto had hoped would give his family a sense of closure instead became a source of information and a curiosity for his American enemy.

Every Japanese sailor and soldier was familiar with the Song of the Warrior, an ancient ballad that captured the centuries of fighting culture that made surrender unthinkable for Kiyoshi Koto and his comrades.

If I go to sea, I shall return a corpse awash;

If duty calls me to the mountain, a verdant sword will be my pall;

Thus for the sake of the Emperor, I shall not die peacefully at home.

By December Lance Corporal Kiyoshi Koto wrote his last letter home. By that time, his unit’s command structure was decimated and the battle strength of his army and its supporting navy was nearly destroyed. As he wrote, the characters on the page of the letter, they were written with shaking hand because Kiyoshi had been wounded in the right arm by a shell during an attack five days earlier. He struggled to carry his rifle because of his injury, and he had not eaten because critical supplies had not reached the beach, let alone the front. Koto understood very well that he was a dead man.

Koto wrote, “Every day there is bombing by enemy airplanes, naval gunfire and artillery fire. No sign of friendly planes or of our navy appears. The transports haven’t come yet either. I have not eaten properly since the 24th of November; many days I have had nothing to eat at all. From tonight on indefinitely, again without expecting to return alive, I am going out resolutely to the front line. Even though I am holding my rifle with a right arm that doesn’t move easily, now is the time for me to dominate a military contest. I must serve as long as I can move at all.

“The Regimental Commander, Colonel Hiroyasu, 16th Infantry, died in battle. The battalion commanders are all either wounded or dead. My own company commander is dead. Two of the platoon commanders have been wounded; one of them entered the hospital for medical treatment and was with me there. In our company NCOs are acting as platoon commanders and privates as squad leaders. At present my company has come down to a total of only 30 men. Of the soldiers in my squad three were killed, four wounded, and at present four in good health are doing hard fighting. As I too am soon to leave for the front lines I should like to see their cheerful faces. The platoon leader, convalescing and almost up, says ‘Go to it Kiyoshi!’”

Koto includes greetings to members of his family and closes, “I am writing this as a farewell letter.”

Saipan 1944. National WWII Museum. Gift of Akita Nakamura.

The answer, as the balance of the war proved prophetically true, was combat with no quarter. And the actions of soldiers letters offer a glimpse into the mind of Lance Corporal Kiyoshi Koto, who also refused to surrender when he found himself in a losing battle. He wrote his farewell letter home, and on the last day went forward to fight and die. He had no illusions about his future. Instead, his thoughts were with home and with his brothers in arms along with a final hope that he could save his family the pain of not knowing what had happened to him.

Dear Dona Page 11

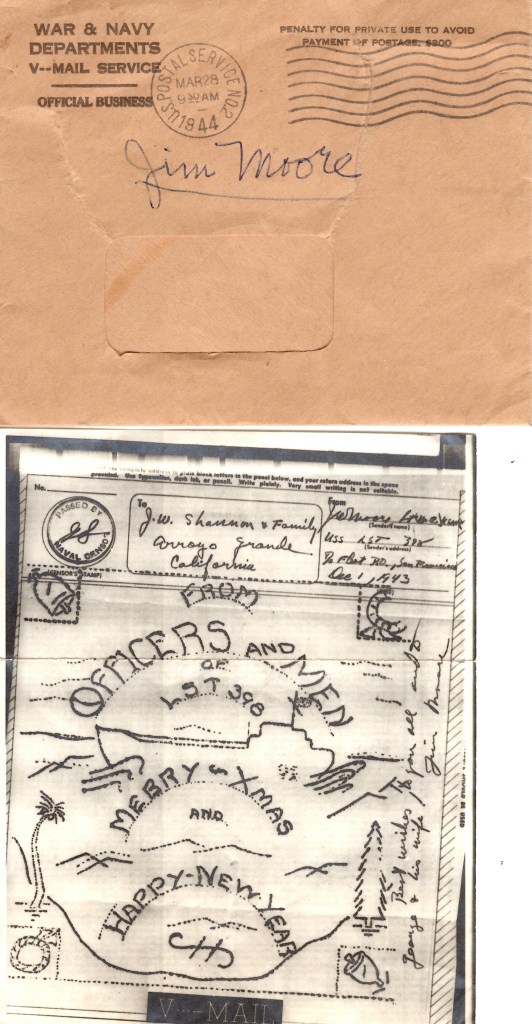

Your fathers original group of four hundred translators that worked in Brisbane in 1943 had been broken up into smaller units and was now spread all over the Southwest Pacific. Many of them now shared the privations and dangers of combat and had taken to carrying rifles and wearing helmets. They operated just behind the lines and were subject to enemy gunfire, artillery and bombs.

Dear Dona 11 coming on February 1st.

* Mexico’s Escuadrón 201, The Aztec Eagles, equipped with Republic P-47D Thunderbolt fighter aircraft distinguished themselves in providing close air support to American ground units as well as long-range bombing strikes deep into Japanese held territory.

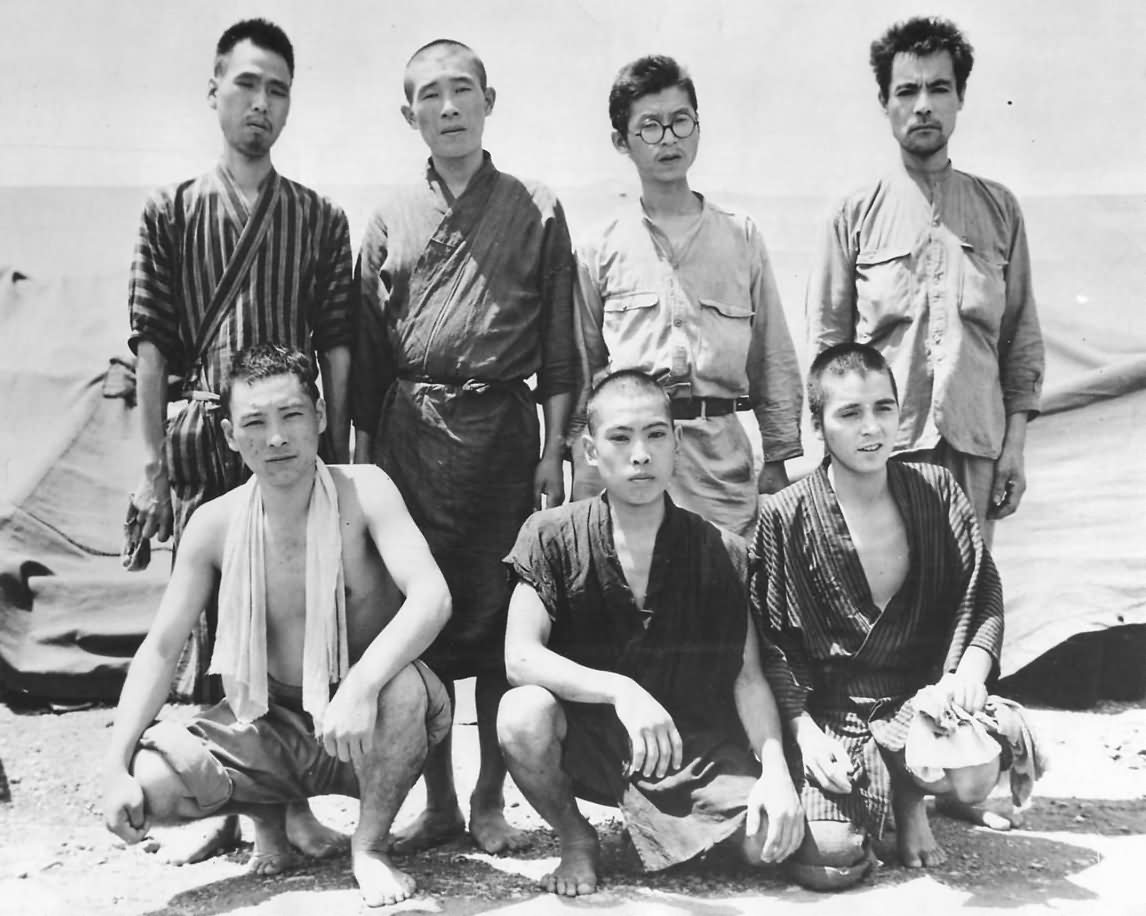

Cover Photo: Captured Japanese soldiers on Okinawa.

Michael Shannon is a writer from California and personally knew the protagonist in this story.