In answer to some questions about the above post you may click on the link below. Michael Shannon

Monthly Archives: February 2025

SITTING DOWN TO DINNER

….With guests.

By Michael Shannon

“The Californians are an idle, thriftless people, and can make nothing for themselves. The country abounds in grapes, yet they buy, at a great price, bad wine made in Boston…” Richard Henry Dana, “Two Years Before the Mast.” 1830

Richard Henry Dana Jr. 1815-1882

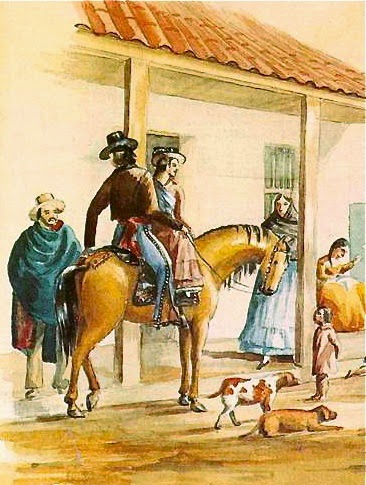

Old Juan, the Mayordomo opened the door at the knock. Sitting their horses outside were Capitan Guillermo Dana and his wife Maria Josefa Petra Carrillo y Dana. Her children, 11 year old Maria Josefa and 4 year old William Charles rode the saddles of the Vaqueros carefully folded into the riders arms. Without dismounting, the Vaqueros bent down from the saddle and gently placed the ninos on their feet.

The patter of little feet was heard and then from between Old Juans legs squirted two little boys, Ramon Branch and his two year old little brother Leandro, called Roman. Barefoot in the dusty patio, they came to a sudden halt, delighted to greet the Dana children. Someone new to play with. La Dona Irelanda, Mrs Branch’s duena came bustling through the doorway, shooshing and fussing as she herded the children inside like a flock of little chickens, squawking and laughing all the way.

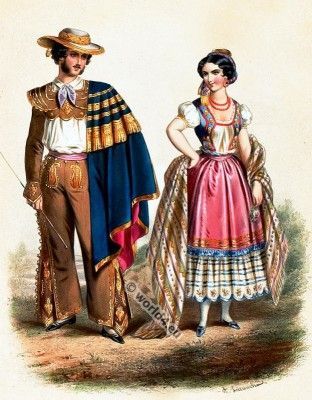

Behind them by the corrals were four of Don Guillermos Vaqueros led by Juan Medina. Dressed in their finest for the occasion in silk lined short jackets adorned with silver Conchos inlaid with jade or ivory buttons fastened with braided frogs. Each man sat his horse as if they were one with the animal. Their decorated and stamped California saddles were adorned with a large horn as large as a soup bowl. Each horse was reined with a beautifully braided Bosal noseband and jáquima. A well trained horse was ridden with almost no guidance from the Vaquero other than a little pressure on the noseband or his knees. Only women rode mares, no Vaquero would ever be seen astride anything other than a Stallion. Each Vaquero believed that they were the greatest horsemen that ever lived. Their spines were stiff with pride and the old saying that they wouldn’t walk across the courtyard on foot is true. A man astride believes his is as noble as any king.

They wore flat brimmed leather hats over silk bandanas, their long hair caught back in ponytails pomaded and shining. As they swung from their saddles their large roweled spurs rung with the sound of jingle bobs tinkling. Shaking out their best clothes, dusting them and arranging everything just so they turned and strode in their soft calf skin boots toward the Cocina never deigning to look back at the hosteler who was leading their horses into the corral. Immense pride in their own stature dripped from them like the morning dewdrops from an Oak.

Juan welcomed the Danas inside waving his arm in a generous sweep towards the host and hostess, Francisco Branch and his wife Manuela who stood in the great room of the newly completed grand hacienda. Manuela stepped forward to greet Josefa, still a stunning dark eyed beauty at 27. They shared an embrace and a brief soft kiss on each cheek as was the custom. Both women had been born and raised in Santa Barbara and were nearly the same age. A quarter century had passed since then and now they were Patronas and managed the households of their husbands vast rancho’s.

Manuela’s maid came forward and to take Josefas “Manton de Manila” but with a small wave of the hand Manuela bade her stay. She bent to look at her friends silk shawl with its elaborate embroidery and the long fringe on its edges, running her fingers along the fine silk from China. “Hermosa, preciosa,” she murmured, speaking in the language of Alta California. Arm in arm the two lovely young women turned to begin a tour of the newly completed home.

The rancheros shared an abrazo as was the custom in the land and walked outside to enjoy the view of the old Arroyo Grande from la Sala. The took their ease in chairs made by the Indians who worked on the rancho. Little Pedro the son of the cook presently arrived with a tray and two glasses which he promptly filled with wine made from the grapes originally grown by the Padres of mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa and transplanted at Capitan Dana’s rancho Nipomo. Taking cigars from those offered by the servant they went through the process of lighting them. Dana leaned back and sent a stream of fragrant smoke skyward. commenting on the flavor. Branch said, “These Cigaros are hand rolled in the Phillipines and came by one of the trading ships just a few weeks ago. The long trip across the Pacifico doesn’t seem to have effected the quality, no?”

The two Don’s sat back and enjoyed their leisure time They were neither indolent or lazy as stated by the first white writers who came to California have stated. Each ran a vast Rancho of tens of thousands of acres. The Spanish word Don was not just an honorific but the description of a man whose literal fiefdom equalled the possession’s of European royalty. Each one was building a community of people dedicated to the advancement of not only their personal interests but the interest’s of their family and retainers.

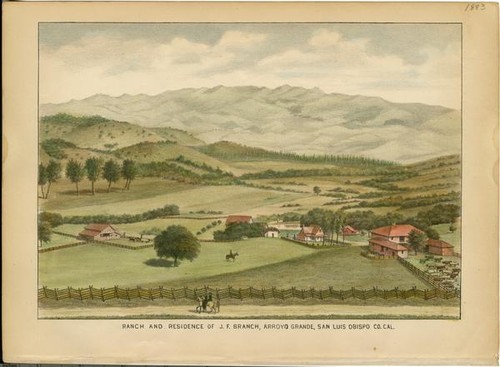

The Hacienda was large and designed to shelter the family and the people who worked for them. The grist mill processed corn and oats to feed the many who depended on Francisco Branch. The clearing of the valley floor, which was ongoing provided growing ground for the many crops and the orchards which provided fruits and nuts to the establishment. Captain Dana did the same.

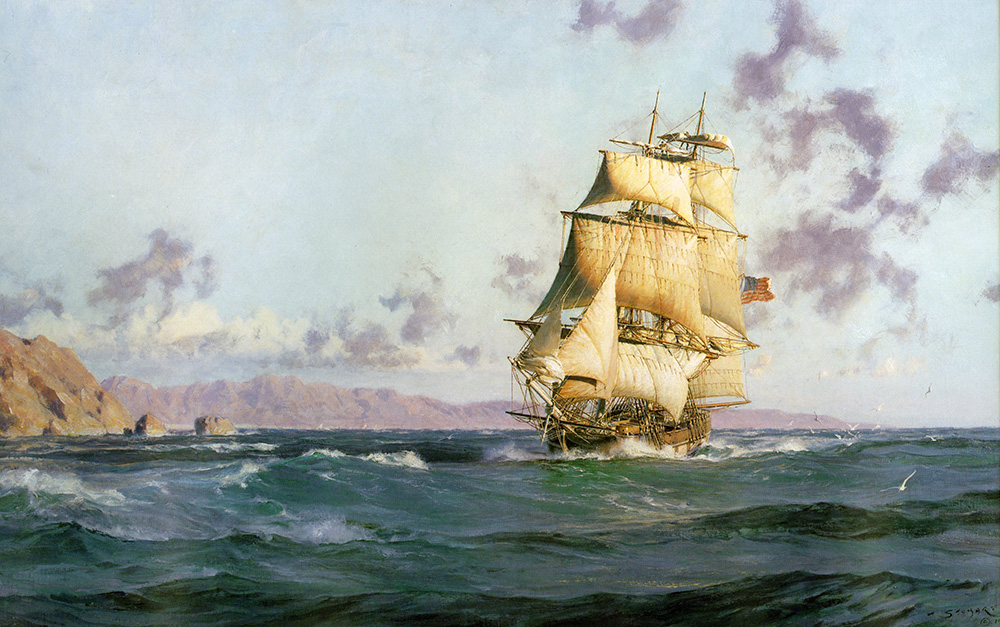

The conversation turned to spring. The spring roundup was approaching and the two men began discussing the organization needed to gather the wild cattle for counting and slaughter. The two men would work with the surrounding Hacendados to put together the Vaqueros, the skinners and the women who would scrape and process the cow hides for shipment. Camp sites, food, cooks, wood choppers and drivers for the carretas that would bring the hides out of the foothills and down to the ranch houses for storage until the ships such as the Alert, Pilgrim, Gypsy or the California of Tomas Robbins called at the cave landing to trade and load hides for shipment to the east coast. Thomas, “Don Tomas” Robbins who owned the Calera de Las Positas Rancho in Santa Barbara and the entirety of Santa Catalina island was Dana’s brother-in-law.

Capitan Guillermo Dana and Don Francisco Branch, both transplanted Yankees, one a sea captain and supercargo on ships trading between the California coast and New England, the other an American trapper and hunter who had come west with the William Wolfskill party of hunters in 1831. They both settled en La Puebla de Santa Barbara where they operated small stores and in Branch’s case, expeditions along the northern coast hunting otters and seals. Otter pelts were traded to the Russians stationed at Fort Ross. The Russian American fur company then sold the peltrie to the Chinese for up to one hundred dollars in the early 1800’s. Branch came in right at the end of the fur trade as most of the sea creatures had been hunted to near extinction by 1840. Although few actual coins were ever traded he built large savings of credits which he used to buy goods for his various enterprises. Though Branch had little education, he was a canny businessman and had come far since his arrival in Alta California.

Both men had converted to Catholicism and became Mexican citizens, married young girls from prominent Californio families and lobbied for grants from the governor of California. This was land confiscated from the Mission establishment when the Mexican government secularized the missions in 1833. The Mexican government confiscated the missions’ properties and exiled the Franciscan friars. The missions establishments were then broken up and their property was sold or given to private citizens. The land was intended to be returned to the Indians who had served the missions but politics reared it’s ugly head and the land was granted to prominent citizens. The Indians, neophytes as they were known lived in the old church buildings, the asistencias, or wherever they could find a place to stay. These Vista or Asistenecias were small mission settlements designed to extend the reach of the Missions at a much smaller cost. Don Francisco Branch was a neighbor of Jose Maria Teodoro Villavicencios who owned the Rancho Corral de Piedra which had two former mission properties, the Corral de Piedra and the smaller Canon Corralitos where the padres had once grazed their horses. from where the two Don’s sat they could look up the Corralitos which still held a portion of the Villavicencios horse herd.

The Arroyo Grande’s Santa Manuela, was in the center of a ring of ranchos. the Nipomo to the east, Francisco Quijado’s Bolsa de Chamisal to the south, and Jose Ortega’s Rancho Pizmo to the west. Neighbors nearby were Don Miguel Avila, Teodoro Avellanes on the Guadalupe and the Punta de Laguna of Luis Arellanes and Emigdio Miguel Ortega. Each one an easy ride by horseback. Visitors were frequent and hospitality demanded thats what is mine is yours. Visits could last for days and even weeks, especially amongst the women and children of the various ranchos.

Women and children learned to ride almost before they could walk. Californio women were nothing like the bonnet wearing side saddle riding women bedecked with ostrich plumes walking their horses through the parks of Manhattan, no, California women rode astride like men and from their earliest age they rode everywhere. Some could throw a reata as well as any Vaquero. Raised to be independent they were nobodies cupcakes. A braided quirt could quell the insolence of any man. Josefa Dana would have seen no need for a sidesaddle if there was ever such a thing in California. And if there was she would have ridden with the same elan as the men.*

At the Branch’s the crackling fireplaces warmed the rooms with old oak wood cut from the abundant coastal oak forests on the Santa Manuela Rancho. The smell of food being prepared in la cocina drifted on the afternoon breeze and added a fillip to the air where the Rancheros sat enjoying the days end.

Old Juan who wasn’t yet old but has been remembered in local lore as “Old Juan” and was Don Francisco Branch’s longest serving employee hustled out to supervise proper care of all the horses. The distances and the lack of roads of almost any kind meant the horses were the only form of transportation and were highly prized. The First horse in California escaped from the Portola expedition in 1770 and with the establishment of the mission system horses were brought up from Mexico and crossed with local wild stock. Padres and their Vaqueros were no less interested in horse breeding than anyone else . By the time of the Rancho era, crossbred Andalusians and arab Barbs numbered well over 25,000. Greater than the human population. Herds lived in semi-feral conditions in the foothills along the coastal areas where most of the ranchos were. Horse racing was a serious business in old California. Visitors remarked on the remarkable quality of California horses. They were so valuable that Captain Fremonts hare-brained attempt to annex California to the United States in 1846 that as his motley group of volunteers simply stole Captain Dana’s best horses in the dark of night, leaving his own worn out remuda and a note confiscating all the horses with a promissory note that could be redeemed for government cash. The only horse left was an old broodmare, to old and fat to ride.

Though there was no telegraph or any way of communicating with ranchos further south, Captain Dana sent a Vaquero to Guadalupe to warn Teodoro Avellanes that Fremont was coming and looking for mounts for his “Army.” Calling out his vaqueros, Don Teodoro made sure that there were no horses in sight when Fremont arrived. Forced to move on Fremonts group camped in the pouring rain at the north entrance of Foxen Canyon. Benjamin Foxen, another Yankee Ranchero was warned by another rider that the so-called army was headed his way. Meanwhile, Captain Dana and his Vaqueros were creeping up on the camp where the miserable, soaking wet Fremont “Army” was camped near todays town of Garey.

It was the practice in those days before fences that whenever a ranchero purchased a horse, he would tie an old broodmare to the new horse with a short rope. The two would run over the fields for a few days until they became fast friends. As a result, to the end of its life, no California horse would ever willingly desert his Caballada, something that neither Fremont nor his men were aware of.

Dana and the Vaqueros moved the broodmare around to where the evening breezes would blow her familiar scent to the grazing horses from Rancho Nipomo. With no warning a stampede began and before Fremont knew what was happening, Dana’s horses were racing across the fields, following their elderly broodmare back home to the ranch. Fremont’s men were once again reduced to marching by Shank’s Mare on their way southward toward the city of Santa Barbara.

The cook and her helpers worked in semi-outdoor kitchen (Cocina). Build with adobe walls about six feet high and a lean-to roof of Vigas closely spaced with smaller willow (El Mimbre) and a covering of reeds from the lower valley woven into thatch. It was almost completely waterproof. The three sided enclosure contained a Horno oven, a circle of stone for a pit fire and hanging above an iron try pot salvaged from a wrecked whaler. There was a small iron stove from a sailing ship with its stove pipe lifting the smoke and heat through the roof of the Cocina. The cooks worked in the building separated from the main house for good reason since fires were common in buildings that had wooden or thatched roofs. It would be a number of years before tile was made in enough quantity to roof the hacienda.

Hand made tables held clay bowls and utensils traded from the small coastal ships that unloaded imported goods and loaded hides at Cave Landing on Miguel Avilas ranch near the outlet of San Luis creek. Though isolated, Alta California benefited by long established trade with the far east.

The men moved inside and stood behind the elaborately carved chairs where their wives would sit. Furniture in the houses was made by the former neophytes who had been trained by the Padres at the mission since the late 18th century. The Chumash had been taught stock raising, agriculture. woodworking, masonry and all the chores required to run a household and since 1833 had been unemployed. For many who remained the ranchos offered near permanent employment. They had worked on every part of the Branch home.

The Chumash and the other Mission retainers who had stayed in the area built corrals, cleared the Monte’s and felled trees for building. Thousands of adobe brick were made by adding water and straw to the sticky adobe soil and then putting the black pudding into wooden molds and laid in rows in the sun to dry. All the old Haciendas were built this way with walls two and three feet thick.

Heated by small and narrow fireplaces where the wood cut from abundant trees was turned on end where it burned slowly. The small fireplaces were efficient and kept the Hacienda warm in winter. The heat generated soaked into the thick adobe walls and radiated back into the buiildings. It was a very efficient form of heating. In the summer the inside of the homes were cool because the thick walls which were shaded by trees stayed cool.

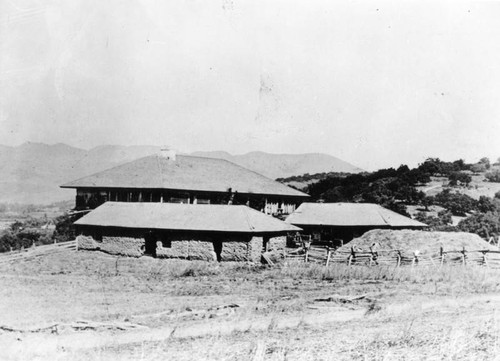

The Hacienda when it was owned by Francis Branch’s son Jose Frederico “Frank” Branch. 1860s

Seamstresses made clothes from imported fabric as well as the wool spun and woven from the sheep raised on the rancho. They made their own soap from the Lye obtained by pouring clean water through the abundance of wood ashes from the fireplaces. Lye was also used to flavor food and to keep insects off the corn crop. Tanning a cowhide requires lye. Mixing lye with animal fats makes soap. Lye will bleach cloth and is used in making paper. Curing meat, fish, fruits and vegetables requires lye. It’s also used to make dyes for fabric.

Both the Hacendados had orchards with apples, lemons, limes, pears, plums and oranges. All grown from cutting that came by pack horse from William Wolfskill’s horticultural nursery near Los Angeles, the first in California. Owned by the same man that Francis Branch came to California with. Both men demonstrated a variety of talent throughout their lifetimes.

Prepared in the cocina were plucked chickens hanging from hooks. Along one wall where irons skillets brought across the old Spanish trail by mountain men like Jed Smith for barter with merchants in Santa Fe or Taos found a ready market in California. Long pack trains of trade goods which would be traded for peltry and fresh horses for the return trip. Along the wall a shelf or two laden with fired clay pots of various sizes mixed with spoons, spatulas and the real treasure, a coffee grinder which had made the long trip from Mexico City to San Blas’s anchorage at Matanchen Bay and then north along the coast by ship.

Coffee had been introduced to the Sandwich islands in the 1820’s and was regularly traded with ships that called at the Hawaiian kingdom. Coffee trees had been introduced to America by Captain James Smith at Jamestown in 1723 and had spread quickly across the continent. Trading vessels could make the run from the islands to California in about three weeks weather permitting. In a single year, in the late thirties and early forties about 25 ships from the United states made the trip around Cape Horn to California. Averaging about 200 days, the small sailing vessels could pay for the cost of their building in single trip.

Economics of trade played a very important part of Hacienda life. With no manufacturing or commercial cities, anything that they needed had to be imported from Mexico or from abroad. The Spanish and Mexican governments tried to restrict trade to keep foreigners from settling in California and had enacted a 100% tariff in the 1790’s. All that achieved was to slow trade with Mexico proper and force the Californios to become active smugglers. The coastline was so long that there was literally no law enforcement and if there had been, the soldiers were easily bribed. They had families to feed too. The two thousand miles between Mexico City and Alta California was a formidable barrier.

To the uninformed 18 year old Yankee, Richard Henry Dana, Alta California seemed backward, the population ignorant and he clearly looked down on the Californios. What he missed is that California was part of one of the oldest worldwide trade routes that ever existed.

The Brig Pilgrim, 86′ foot at waterline and a 21 foot beam Leaving Monterey Bay. 1834

The famous silver fleet or plate fleet; from the Spanish: plata meaning “silver”, was a convoy system of sea routes organized by the Spanish Empire from 1566 to 1790, which linked Spain with its territories in the Americas across the Atlantic. The convoys were general purpose cargo fleets used for transporting a wide variety of items, including agricultural goods, lumber, various metal resources such as silver and gold, gems, pearls, spices, sugar, tobacco, silk, and other exotic goods from Spains overseas territories of the Spanish Empire to the Spanish mainland. Spanish goods such as oil, wine, textiles, books and tools were transported in the opposite direction.

The West Indies fleet was the first permanent transatlantic trade route in history. Similarly, the related Manila galleon trade was the first permanent trade route across the Pacific. The Spanish West and East Indies fleets are considered among the most successful naval operations in history and, from a commercial point of view, they made possible the key components of today’s global economy.

The Manila galleons mostly carried cargoes of Chinese and other Asian luxury goods in exchange for New World silver. Silver prices in Asia were substantially higher than in America, leading to an arbitrage opportunity for the Manila galleon. Every space of the galleons were packed tightly with cargo, even spaces outside the holds like the decks, cabins, and magazines. In extreme cases, they towed barges filled with more goods. While this resulted in slow passage that sometimes resulted in shipwrecks or turning back, the profit margins were so high that it was commonly practiced. These goods included Indian ivory and precious stones, Chinese silk and porcelain, cloves from the Moluccas islands, cinnamon, ginger, lacquers, tapestries and perfumes from all over Asia. In addition, slaves, collectively known as “chinos” from various parts of Asia, mainly slaves bought from the Portuguese slave markets and Muslim captives from the Spanish–Moro conflict were also transported from the Manila slave markets to Mexico. Free indigenous Filipinos also migrated to Mexico via the galleons where the crews would jump ship. These men comprised the majority of free Asian settlers the “chinos libres” in Mexico, particularly in regions near the terminal ports of the Manila galleons, San Blas and Acapulco. The route also fostered cultural exchanges that shaped the identities and the culture of all the countries involved.

In an age where time was measured differently, the long voyages or transportation times to get goods from Spain or the Phillipines to the Branch’s rancho was simply a factor that the Hacendado’s calculated.

The cooks in the kitchen didn’t care. They served Francis Branch and the where and the when of goods came from was of no matter. Their job was the feeding of the family and its retainers.

Red peppers, green peppers, dried tomatoes, garlic flowers, bay leaves, all strung together in multicolored bunches hung from a wrought iron rack hung in the corner of the room over a heavy table where the two cooks stood working. The older Mexican ladies from Sonora showed that the speed at which they worked belied had little to do with their ample size. They chattered with a sinuous melodious stream of Spanish mixed with Chumash and an occasional English word as they worked, laughing and teasing, especially the two little part Chumash girls that were the scullery maids. Laughter always made the food taste better they said. The little brown boy who swept the hard packed floor scuttled about trying to avoid the gentle kicks aimed at him when he got underfoot.

Chubby fingers flashed and the home ground and mixed flour from the Branch mill hung in the air as they rolled the batter into little balls, twirling and patting tortillas into shape with a staccato rhythm that mimicked the tattoo of little drums.

Bubbling over the fire, a pot of frijoles de olla and another of carne con chile steeped. Stores of wheat, beans, lentils and dried vegetables and fruit were stored in finely woven Chumash made baskets some so tightly made they would hold water. Some baskets had woven covers some were covered by a piece of wood with a small stone to keep out the mice who were everywhere in this little rodents paradise.

Dried salmon from the creek, fish from the reef and open sea along with dressed rabbit hung from the vigas overhead. Clay jars of salt, peppercorn, dried onions and lentils plucked from the creek banks sat on shelves with native California beans like Lima beans, butter and black-eyed beans along with both dark and light kidney beans, cranberry beans and heaps of wild blackberries gathered in the valley floor where armed Vaqueros protected the pickers from the numerous grizzly bears who also laid claim to the bounty.

From the Hacienda on its hill it was less than a mile to the bear pit where Branch and his vaqueros regularly caught and killed the monsters. The bears could and did carry off entire steers and other livestock. There were yet parts of the valley floor where no man went. Down the valley on the El Pizmo the swampy monte was so dense as to be impassable by man or horse, but not the Grizzly. Choked with wild berries it was exactly to the taste of the bears.

The valley was a paradise, the soil so rich that it was said if you threw a rock on it, it would grow pebbles.

As the sun fell towards dusk, the dinner bell began to clang from the Cocina, where the cook and her helpers were preparing to serve. The boy came out onto La Sala and murmured that La Cena Familiar was being brought in by the young women who served the cook for she was responsible for feeding nearly everyone on the Rancho. As the women were seated, servants brought out the meal.

The men had seated the women and then pulled out their own chairs and sat. The other guests took their places, before the door opened, the savory smell of food drifted into the room. Backing through the door the cooks laid on the table the big pot of Frijoles de Olla, red beans cooked with red chiles, wild onions from the creek, next a platter of chicken, breaded with crumbs from baked tortillas. This was followed by Squash blossom fritters garnished with salt, and wild sage gathered from the hillsides around the Hacienda then sprinkled with goat cheese made from the Rancho’s goat herd. A Chinese tureen filled with vegetable soup made from potatoes, carrots, wild leeks, onion, chopped cabbage from the kitchen garden and then sprinkled with ground red pepper. A pot of pumpkin soup arrived, an old Chumash recipe made from sliced and cubed pumpkin, sliced leeks, chicken broth, cows butter and pepper. The butter was something the Chumash didn’t have but served as examples of the blending of different cultures. The main dish which came in last was on a large figured platter brought from China. White porcelain with indigo blue figures it was heaped with braised short ribs smothered in onions, carrots, celery potatoes, parsley and sage. Each rib swimming in a sauce made from the Mission grapes and Brandy from the Calvados region of France. Crossing the Atlantic Ocean to Vera Cruz, Mexico and carried by pack train and wagon, the bottle had made the journey to California.

A heaping dish of fresh made tortillas, rolled and eaten as a compliment to the meal was laid out. Each of the adults ate from imported china which came east across the Pacific from the Philippines and glass goblets made in the city of Puebla, Mexico. Napkins of the finest embroidered linen were at each place setting. Sugar horns from the Sandwich Islands and bowls of pepper and salt were scattered about.

When the meal was complete the brandy was served for the men and Sherry for the women. At each place setting the servants laid a tortilla rolled with chocolate inside as a savory.

The guests at the table represented the variety of Californio peoples. The host was an American from Scipoio, New York. His principal guest, Captain William Dana a Bostonion. Their wives, both from Santa Barbara, the center of Californias largest pueblo, both from prominent families who had lived in Alta California since its founding. Mrs Branch’s sister Maria was married to Michael Price who owned El Rancho Pizmo. Price was from Bristol, England. The Priest who gave the blessing was a Spaniard educated in a Franciscan university in Europe, the Vaqueros were mostly Chumash or descendants of mixed marriages. The current term mestizo was rarely used in mission records: more common terms were indio, europeo, mulato, coyote, castizo, and other caste terms for someone of mixed breed. Some of them were of Indian and Spanish blood or from the Chumash or other native tribes. The chief cook was Chinese, lured from a transpacific trader and at least one vaquero, a Kanaka from the Sandwich Islands.

The Californios were neither indolent nor backward. Francis Branch had a school in his home for his own and the children of the men and women who worked for him. His account books, along with William Danas are part of the historical record. The descendants of those families live in and about San Luis Obispo county to this day. Their legacy exists in the names of streets, schools and their extended families. They were pioneers in every sense of the word and they made the world we live in today.

Richard Henry Dana was wrong.

“Were the devil himself to call

for a night’s lodging, the

Californian would hardly find

it in his heart to bolt the door…”

Diary of

Walter Colton

Monterey, 1850

The old Branch Adobe Hacienda about 1860. Branch Mill Road in foreground.

The old Branch home in 1887, slowly melting away. It is completely gone now.

*With the flood of Easteners during the gold rush, mores changed and sidesaddles became de riguer for women. Still, on the ranches women and girls persisted in the old practice of riding astride. My own great-grandmother shocked the staid gentry of Santa Barbara by doing just that in the first La Fiesta parade in 1924. Born and raised on the old San Juan Canon de Santa Ana Rancho she was not one to care what anyone thought. She was admired in the family for her independence.

Michael Shannon grew up on the old Rancho Santa Manuela about a mile from the original Hacienda. He went to Branch Elementary school and knows many of the Branch descendants. Many of the Branch grandchildren were still alive when he was a boy. Stories abound.

Dear Dona 11

Moving Up

Michael Shannon

Your fathers original group of four hundred translators that worked in Brisbane in 1943 had been broken up into small units and was now spread all over the Southwest Pacific. Many of them now shared the privations and dangers of combat and had taken to carrying rifles. They operated just behind and into the lines and were subject to enemy gunfire, artillery and bombs. War zones are dangerous places and even those that see no actual combat are subject to the whims of the monster.

After Morotai headquarters moved up to the island of Leyte and promptly discovered something entirely new. The translators as with all staff, headquarters and support troops rarely knew what was going on in the wider war. As they advanced in the Phillipines the war began to widen out. The days of jungle fighting were nearly over. Leyte with a population of just 900,00 most supporters of the Americans was divided by a mountain range with the southern portion of the island very lightly populated The flanking coastal plains allowed the use of tanks and other mobile units for the first time. Fighting was heavy but the Japanese were pushed up the island in a series of very sharp battles. The campaigns success allowed the planning for the invasion of the main island of Luzon to go forward in a hurry.

Since MacArthur had been ordered out, Corregidor had been surrendered, the Bataan death march had taken place and most combatant Americans had been locked up in concentration camps. MacArthurs Filipino Scouts had also surrendered but not all. Army Navy personnel and the Filipinos had disappeared into the hills of the Phillipines and for three years had been roving the country formed into Guerrilla groups. (1) Filipino ex-soldiers, American service members, Naval officers and Australian and Dutch soldiers had formed lethal bands of Guerrillas who preyed on Japanese troop movements and supply convoys. The Dutch and Australian stole or cobbled together radio sets with which they sent messages to Army headquarters in Australia. They reported on Japanese ship movements and disposition of army units.

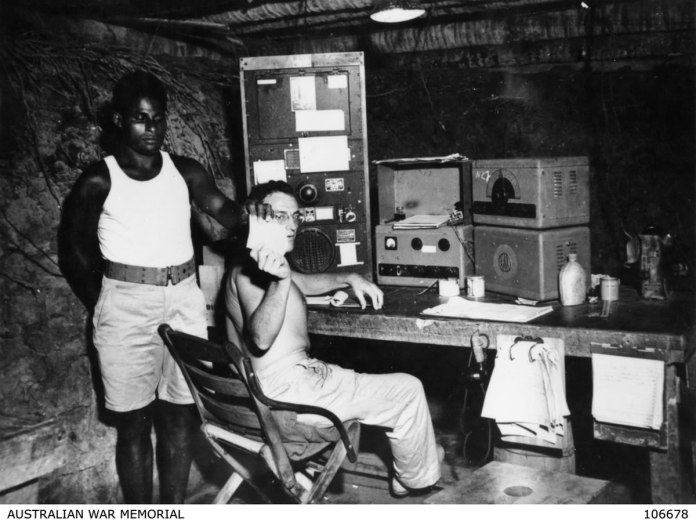

MacArthurs command arranged to deliver better radios, generators to provide electricity to the Coast Watchers were constantly on the move. A message sent in the clear or in code could be tracked by Japanese rangefinders so they picked up and got out of Dodge immediately after sending. It was highly dangerous work but invaluable to the allies. Radio message were synced with MIS translations and throughout the three years before the return the command had a clear picture of almost everything the Japanese were up to.

The base radio station dugout of the Coastwatchers Ken network in the Solomon Islands. Photo: Australian War Memorial.

During August and September 1942, 17 military coast watchers (Seven Post and Telegraph Department radio operators and 10 soldiers) and five civilians were captured as Japanese forces overran the Gilbert Islands. Imprisoned on Tarawa atoll, they were all beheaded following an American air raid on that island. The coast watchers and their teams, mainly native islanders were constantly on the move. They faced starvation, boredom and feared for their lives but none attempted to escape. Though mostly resident civilians who had worked for the rubber plantations and the petroleum companies they received nothing for their work. It wasn’t until late 1944 that that the Anzacs bestowed military officer rank on them so if killed their families would receive a pension.

Coastwatchers were also involved in organizing supplies for the Guerrilla bands. They received supplies and arms from American subs, Dumbos (2) and the famous Black Cat Catalina flying boats. They also rescued downed flyers and other military personnel who were downed or sunk along the island chains. These included the future US President, US Navy Lieutenant John F. Kennedy, whose PT 109 Patrol Torpedo boat was carved in two and destroyed by a Japanese warship in the Solomon Islands. After the sinking, Kennedy and his crew reached Kolombangara Island where they were found by Coastwatcher Sub-Lieutenant Reg Evans who organized their rescue.

In the Philippines they were to witness the roots of the local Resistance which represented the cultural and socio-economic diversity of the Philippine Islands. From socialist peasant farmers the Huks, middle school teachers, ROTC youths, to Moro (Philippine Muslim), the range of the men and women who participated in the struggle against the Japanese Imperial Army was seemingly inexhaustible.

Officers at headquarter were initially astounded when groups began showing up. slipping out of the jungles like wraiths, armed and dangerous.

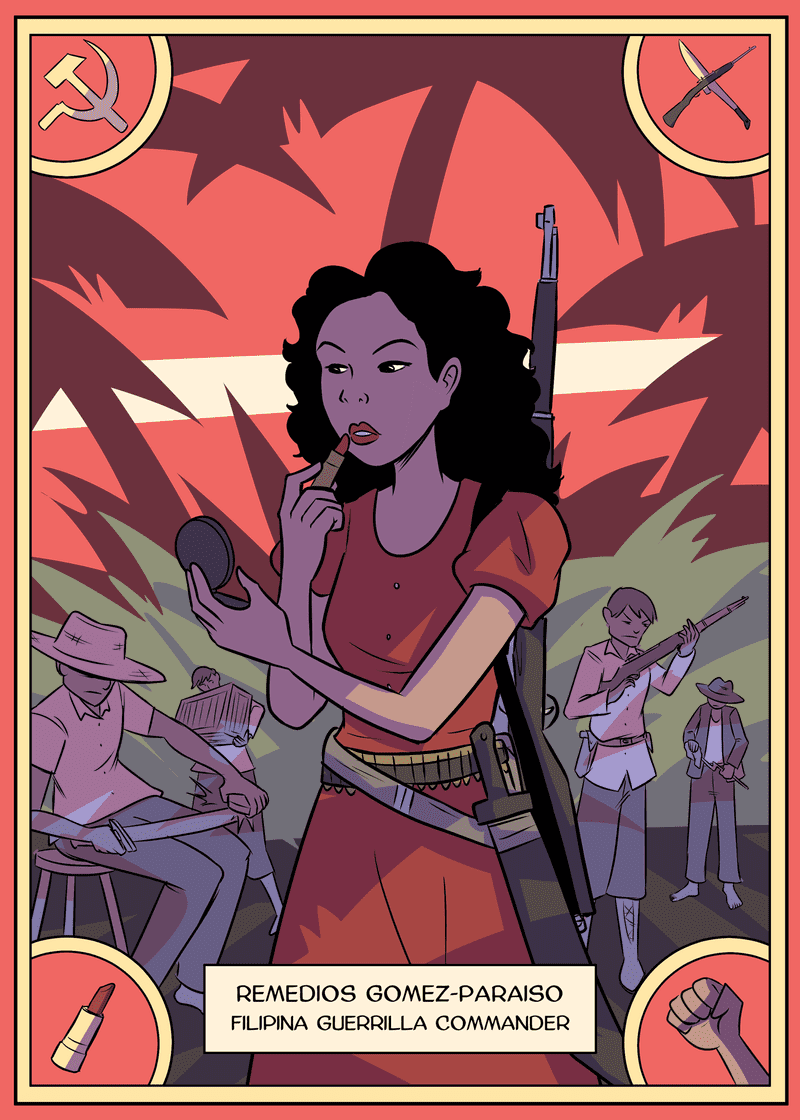

At least 260,000 strong, the guerrilla forces were ill-equipped and poorly armed. They depended on local civilians for food, shelter, and intelligence. Several units recruited women guerrillas. Some took up arms and served side by side with men, including journalist Yay Panlilio and Huk commander Remedios Gomez-Paraiso also know as “Kumander Liwayway.”

Remedios Gomez-Paraiso, Kumander Liwayway. Photographer unknown. 1945

Remedios Gomez-Paraiso was an officer in the Hukbalahap, a communist guerrilla army known for their daring attacks on Japanese forces. Born in Pampanga, Gomez-Paraiso joined the guerrillas after her father was killed by Japanese forces. Known for going into battle wearing her signature red lipstick, Gomez-Paraiso quickly rose in the ranks to become a commander of a squadron. At one point, she had two hundred men under her command. Perhaps best known for the “Battle of Kamansi” in which, despite being outnumbered, Gomez-Paraiso’s squadron forced Japanese forces to retreat. After the war, her Hukbalahap Guerrillas continued their revolution against the democratic Philippine government until 1948, when her husband was killed, and she was captured. She was released and went on to become a vocal advocate for the recognition of Filipina Guerrillas.

In a marriage of convenience the guerrillas, some who had been fighting the Americans invaders since 1898 when President McKinley annexed the islands against their wishes. In the southern Phillipines, the Muslin Moro had resisted the Spanish conquest since the since the end of the 15th century. This religious war only ended with the annexation by the US in 1898. The Muslim Moros then fought the United States and finally the Japanese. Resistance was baked into their DNA. Because they hated the Japanese more they saw the alliance as temporary but expedient. Filipino Guerrilla groups fought right up until the end of the war. (3)

A guerrila group on Leyte, Phillipines, 1944. National Archives photo.

On January 25th 1945 your dad and his MIS team walked aboard LST 922. They were bound from Leyte to the island of Luzon. Just nine days before 175,00 American troops supported by over 800 ships had gone ashore at Lingayen Gulf, ironically the same beaches employed by General Homma’s Japanese forces in December, 1941.

General MacArthur himself went ashore on S-Day. There were no histrionics this time. Luzon which he had abandoned in 1941 was not only his personal goal, but erasing the embarrassment which was compounded by secretly fleeing during the Phillipines during the dark of the night in a little PT boat, PT-32 commanded by LTJG John Bulkeley (4)

LST 922 at Morotai Island, Dutch East Indies, December 1944. USN Photo

Your dad’s MIS team hefted their barracks bags and walked up the ramp for yet another trip by an LST. Commanded by Lieutenant, Junior Grade Ronnie A Stallings who was a regular Navy officer. A special but not uncommon type in the WWII Navy, he was a Mustang. Mustangs as opposed the thoroughbred Naval Academy officers were generally outstanding enlisted men promoted up from the ranks. Born in Brooklyn New York in 1924, Stallings enlisted in April 1941 and went to sea as a 17 year old later that year. He was an ordinary seaman. Assigned to a Landing Craft Infantry 487 or LCI. LCI 487 was typical of this type of LCI. It was newly built and the crew was young and inexperienced. The skipper, Lt. Stewart F. Lovell was the “Old Man” on board. Born in Manchester, N. H. on May 26, 1907, he was 36 years old when he set sail on the 487. However, most of his crew was seventeen, eighteen and nineteen year olds. His young crew gave their Skipper the nick name “Baggy Pants” because he did not acquire a proper fitting uniform after losing a lot of weight while onboard. LCI’S were 158 feet long, just over half a football field and only 23 feet in the beam. With the bridge being high and the hold being empty she rolled like a “Drunken Sailor” to use a Navy term. There are other terms for unseaworthy ships but most are unprintable. A very strong stomach would be required and perhaps the skipper didn’t have one. The Executive Officer – Ensign James T. Clinton was nicknamed “Boy Scout” because he was pale, clean cut and did not drink or smoke. Ronnie Stallings was present during the landing in North Africa in 1942 and at D-Day, June 1944 where his little ship, derisively known as “Waterbugs” by disdainful Admirals disgorged over two hundred GI’s of K Company, 18th Regimental Combat Team of the 1st Infantry Divion onto Utah Beach. Unable to back off the beach, 487 was pounded by German artillery and temporarily abandoned. Stallings was taken back to a survivors camp in England located at Greenway House the estate of Agatha Christie. With only the clothes on his back he was given an overcoat and a bag with a broken tooth brush and a razor with no blades.

His next ship was the fleet oiler USS Salomonie. He caught up with her in Panama in July as she passed through the canal on the way to Milne Bay, New Guinea. By this time a Quartermaster or QM, he would stand watch as assistant to officers of the deck and the navigator; serve as helmsman and perform ship control, navigation and bridge watch duties. QMs procure, correct, use and stow navigational and oceanographic publications and oceanographic charts. Thats the official description. Navy slang is “Wheels” because the begin by steering ships which is no mean feat. (5)

USS Salamonie Ao 26 and an LCI unloading at Utah red Beach Normandy, France June 5th, 1944.

Salamonie sailed for the Pacific Ocean via the Panama Canal on 8 July 1944 and reported for duty to Commander Service Force, US 7th Fleet, at Milne Bay, New Guinea, on 23 August. Salamonie joined the Leyte invasion force in Hollandia on 8 October 1944 and later supported both the Morotai and Mindoro strike forces. She spent the final months of the war supporting Allied operations in the Philippines after Ronnie Stallings transfer to the LST.

By the time Stallings arrived at Milne Bay he was a Chief, a rank achieved in just three years, a feat that could only be achieved in wartime. In peacetime it could take 20 years of duty, and he was just 22 years old. A 22 year old former enlisted swab made it to Chief Quartermaster. At Milne Bay he received a commission as a Lieutenant Junior Grade, and his own ship. No stateside classes, no practice, only his three years at sea as his training ground. As a newly commissioned officer he walked up the gangplank as the senior officer and Captain of his own ship Landing Ship Tank-922. He could never have imagined as a seventeen enlisted recruit that he would end up here.

Trailing their gear the team came aboard 922. Led by your father, the leader with the rank of TEC 4. Trudging into the ship were his crew, Jim Tanaka, Michael Miyatake, Henry Morisako, and Tabshi Uchigaki. Masai Uyeda, and Tsukasa Uyeda followed. Seven men, all headed for Eleventh Corps headquarters at Lingayen. General Eichelberger commanding. By this time they undoubtedly knew that the end was coming for the empire of Japan.

Eleventh Corps Badge, WWII

Dear Dona,

12th page next week Feb. 15th.

Closing the Ring*

1) Guerrilla from the Spanish Guerra. Guerrilla literally translates to “little war”. It’s a diminutive of the Spanish word guerra, which means “war”

(2) Dumbo refers to large aircraft such as the B-17 or B-24 heavy bombers which were modified to carry a large lifeboat that could be dropped to survivors at sea. They were largely replaced by the more versatile PBY Catalina which had a longer range and could land on water. The Catalina has been Largely ignored by most historians but was a major factor in air-sea rescue, insertion and extraction of personnel from Japanese held islands. The Catalinas also delivered supplies to Coastwatchers and guerrilla groups. The term Black Cats or Nightmare is the name given to the Naval and Army squadrons who flew these missions by night.

(3) The Moro people in the southern Phillipines have fought invaders from the fifteen hundreds right up to the present conflict with independent Philippine government. Nearly five hundred years of almost constant conflict has made them a formidable force.

(4) LTJG John Bulkeley is portrayed by Robert Montgomery in the 1945 film “They Were Expendable.” Directed by John Ford and co-starring John Wayne and the inestimable Donna Reed. In my opinion one of Ford’s best films. It impresses with its portrayal of the utter hopelessness of those last days before the surrender of the Phillipines to the Japanese. The dinner scene with the officers and the nurse, Donna Reed is utterly in tune with the times. By todays standards it is mawkish but it wasn’t made for now but during the war when people felt differently than they do today.

(5) The author served in the Merchant Marine. Steering a ship as long as two football fields and weighing nearly 30,000 tons is not for the faint of heart.

(6) Technician fourth grade (abbreviated T/4 or Tec 4) was a rank of the United States Army from 1942 to 1948. The rank was created to recognize enlisted soldiers with special technical skills, but who were not trained as combat leaders. Technician fourth grade. The T/4 insignia of a letter “T” below three chevrons.

*Apologies to Sir Winston Churchill.

Michael Shannon is a writer from California. He knew Mister Fuchiwaki personally.

My Neighborhood, Down the street no. 9

The kine da Kine. Ea, the babe. She smaat too. From my friends they live down the street. You get this if you’re from Pearl city, Hawaii.