Chapter thirteen

Elwood, his name was Elwood Cooper and he owned the large Elwood Ranch in what is now Goleta and the adjacent hills. His first name lingers in several local place names including the oil fields. There are Elwood Canyon, Elwood School, Elwood Station Road, and a Goleta neighborhood. He ran cattle. He was a horticulturist and was best known for importing millions of Ladybugs from China to California which wiped out the black fungus that was killing walnut trees and saving that industry. He also imported the first Blue Gum tree which he though might be a good source of lumber. There are still thousands of Eucalyptus planted in wind breaks all over Southern California. This turned out not to be a wise choice.

After the death of his wife in 1909 he sold out and lived the rest of his life at Santa Barbara’s Arlington hotel. The ranch was sold to the Doty family who kept the business until 1921 when it was foreclosed, auctioned off and was essentially dormant until 1927 when an exploratory oil well was drilled there by a company from Texas.

The first oil discovery in the area was in July 1928, by Barnsdall Oil and the Rio Grande Company, who drilled their Luton-Bell Well No. 1 to a depth of 3,208 feet into the Vaqueros Sandstone. After almost giving up they not only struck oil, but had a significant gusher, initially producing 1,316 barrels per day. This discovery touched off a period of oil leasing and wildcat well drilling on the Santa Barbara south coast, from Carpinteria to Gaviota. During this period, the Mesa Oil Field was discovered within the Santa Barbara city limits, about 12 miles east of the Elwood field. The Elwood Field contained approximately 106 million barrels of oil, almost all of which has now been removed. The field has been abandoned.

Elwood piers and wells. Elwood Field, Goleta, CA

Barnsdall moved Bruce up to Elwood in early 1929. Almost all the wells were being whipstocked trying to reach the oil sands covered by hundreds of feet of seawater in the Santa Barbara channel. His expertise was in high demand. The drill strings were boring diagonally down in to the field like the tentacles of a squid. The whipstocks themselves never saw the light of day, snuck in at night because no one wanted the competing oil company on the neighbor’s lease to know just what was going on.

The business was still the wild wild west. There was no government control on production. Small producers took no prisoners they just drilled and drilled. Since wells typically produced the greatest amount of oil when they were still new, the impetus was to never stop drilling. The big companies were no better. Over production was taking its toll at the gas pump but no one in the business cared. Neither did the Hoover government. The public liked the idea of .22 cent gasoline.

Times were still pretty flush during the postwar boom. Car companies were turning out automobiles as fast as they could and Ford, especially Ford with its emphasis on utility and low price was driving car production at a breakneck pace. In 1929 Henry Ford raised wages to $7.00 a day. The other auto makers promptly sued him citing unfair labor practices.

Wages in the oil fields were also high, seven to eight dollars a day. The length of a tour was now just 8 hours down from twelve. Things were better for Bruce and Eileen because he was able to spend a little more time at home though it also meant that the rigs now required two crews a day to make hole. As a tool pusher he was now required to supervise both crews not one.

It was rough work. Bruce wasn’t out of danger yet. In 1930, 67 oil workers were killed on the job. Blowouts, falling rigging, toppling derricks, explosions and fire were always a danger. There was rarely at time when there wasn’t something burning in the fields. Barnsdall, operating all over California sent them back to Oildale. a place where they lived for nearly a year. Bruce came home one day with the skin ripped from his fingertips to nearly his elbow peeled back. At the rig they had smeared some grease on the open wound, laid the skin back down and wrapped it in a dirty undershirt and sent him home. My grandmother opened it up, cleaned the dirt and stickers off, slathered it with Vaseline and wrapped in in a clean bandage which she cut from a sheet. He went back to work the same day. They were both tough people.

In 1929/30 they lived in Bakersfield in a house for the first time that was big enough for the whole family, Bruce Eileen and the three kids. It had enough bedrooms for each kid which was the first time that had happened. It was considered a luxury by the children because no one had to sleep on the couch or the screened porch. Wonder of wonder it had indoor plumbing. A faucet in the kitchen and a bathtub. No toilet though, you still had to use the “Backhouse” to do your business.

Robert Mariel and Barbara Hall, 1930. Hall Family photo

Bruce was getting a reputation for knowing what a well was doing. He could tell by smell and taste what was happening a thousand feet down. He could hear in the creaks and groans, what she was thinking. He had the drillers sense of where she was going. Kneeling on the platform you would have seen him sniffing at the casing head, taking a finger and tasting the liquid mud used to lubricate the drill string. How hot was the mud flooding up out of the well? What did it smell like, was that hint of rotten eggs? When traces of crude came up getting a little on the fingertips and touching it with the tongue to help predict its gravity, was in light and sweet or thicker, could it be chewed. There was even a difference when you wiped your hand on a rag, did it soak right in or stick to the surface. Was there gas coming up, how much pressure was pushing it? There were a thousand indicators, the well was telling you its story. It had to be read on the spot for there was little scientific measurement in the oil patch just yet.

He always said that the kind of things you see in a movie, wells blowing up or a gusher blowing vast amounts of oil skyward could and would get your fired. Crude was money and the big men in the office wouldn’t be happy if a well got out of control. If you’re senses told you what was coming next you were a valued worker and grandpa was that. He had eleven years on the job and the experience was paying off. There were just a few thousand men working the rigs and people as good as Bruce were worth their weight in gold, or oil as the case may be. Word gets around.

Everything was looking pretty rosy. All three kids doing well in school, Mariel would be in high school in a year, Barbara in seventh grade and Bobbie in fourth. The kids were old enough now that their constant moving about had taught them how to quickly make friends. How to spot the popular kids who were school leaders and elbow there way into the group. Their parents sat them down and counseled them on the best way to survive as the constant new kid. Moving two or three times a year from school to school strengthened their social skills. I remember my mother, Barbara, the second child could make a friend in about two seconds.

Something bad was lurking in the United States and the world though. On the surface was the gloss of good times shown brightly but they masked something sinister. By the end of the decade cracks would begin to show though no one seemed to understand the why or what of it just yet. Let the good times roll.

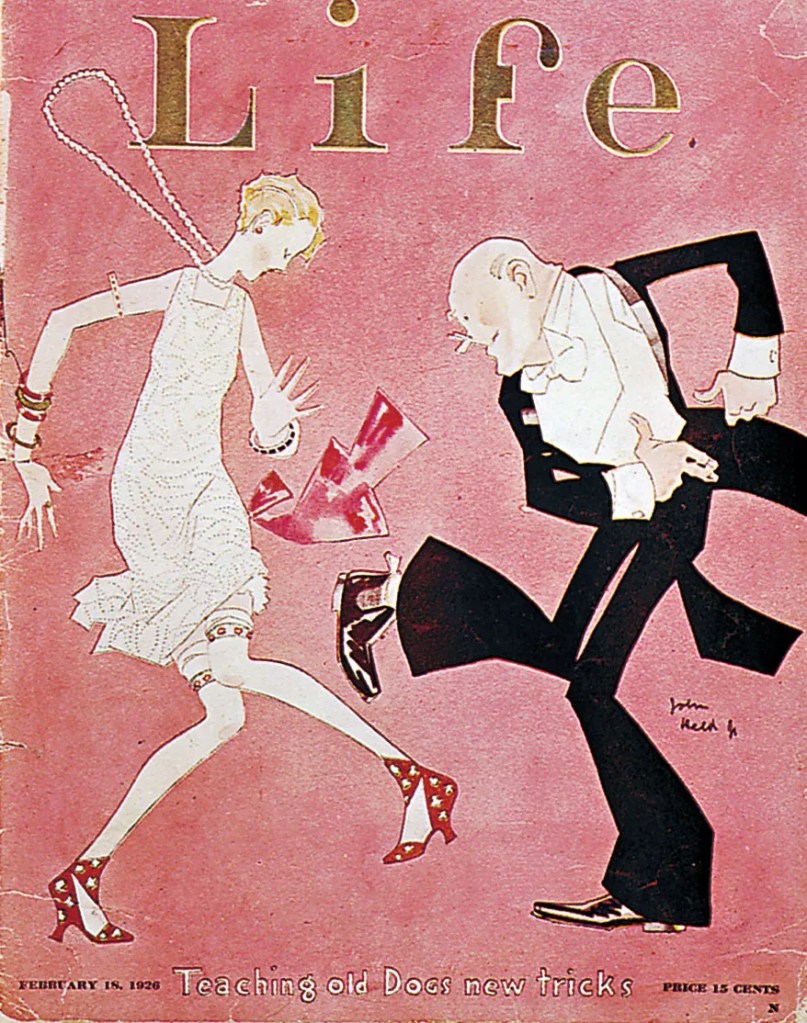

Life magazine cover. Art, John Held JR. November 1926

All during the twenties in the aftermath of the war the times were good, very good. Society had rapidly changed. The old song which opined that soldier boys who had seen gay Paree wouldn’t want to go back to the farm was true. Young people saw skirts go up, way up. Flappers wore silk stockings. They rolled them over a rubber band just below the knee slipped a flask of bootleg whiskey under their garters and shimmied like their sister Kate. Hair was bobbed. Silk undies, just a chemise and a pair of step-ins, let’s party like 1929.

Miss Bee Jackson 1925, The Charleston Girl. British Pathe photo. Youtube.

Henry Ford was turning out the Flivver by the millions, they cost just over two hundred dollars and the kids soon discovered that petting on the back seat was a delight. They wanted to go and party with Jay Gatsby on long Island. F Scott Fitzgerald helped open the door.

It Wouldn’t last.

Chapter 14, coming soon. Disaster.

Michael Shannon is a writer. These stories come from his mothers side of the family many of who spent more than sixty years in the oil patch.