Chapter 13

Down In The Dumps

Michael Shannon

They pulled out of Goleta, the two 1927 model T’s loaded with whatever they could fit in around the kids the rest tied on the trunk platform at the rear. North from Goleta. The road, not by any means a highway yet wandered along the coast, a fine view of the Pacific Ocean until they entered the little valley at Gaviota where they would turn inland.

Entering Gaviota pass. Goleta Historical Society

The sharp little valley named by the Portola expedition for the unfortunate seagull it’s hungry soldiers killed and ate there in 1769 was little changed. The narrow break in the Santa Lucia mountains, the only one for a hundred miles in any direction was now wide enough for vehicles but just barely. Bruce and Eilleen were slowed by road work through the narrow pass because the old rusty steel bridge over Gaviota creek was being replaced by a modern one and contractors had begun laying asphalt north from Santa Barbara but once they were north of Refugio canyon where the hide droughers had once loaded Richard Henry Dana’s Bark Pilgrim with dried cow hide, there was only a graveled road for the next 45 miles.

They drove under the Indian Head rock at Gaviota which my mother didn’t like, she though it might fall down on their car, something she never got over. Then up the hill to Nojoqui pass and down to Buell’s, from there on it was going to be a dusty trip and they wouldn’t see another paved road until Santa Maria. They stopped at the tiny town on Rufus Buell’s Ranch where ate they lunch at the only cafe in town, Anton and Juliette Andersen’s Electric Cafe, featuring Juliette’s soon to be famous pea soup recipe.

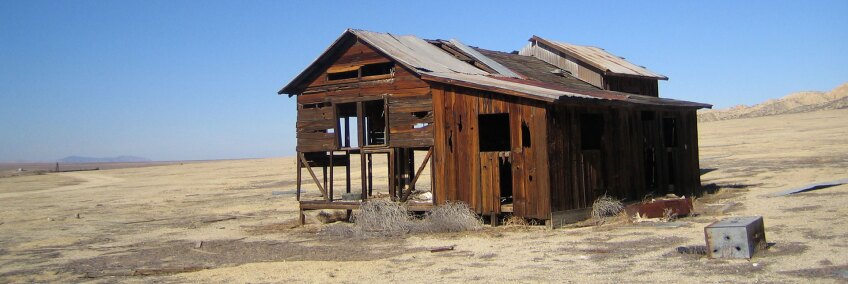

The two cars burdened with most all they had, two couples and four kids passed by the Pacific Coast Rail road warehouse in Los Alamos where Bruce had once worked humping 90 pound sacks of grain from the ranches nearby and then they turned up the Los Alamos valley headed for Santa Maria. On the way they rolled through the old Graciosa townsite, Casmalia, and Orcutt where the men had their first jobs in the oil fields more than ten years before. The little company town where they had lived was still up on the hill above Orcutt but was falling into ruin as nearby towns with rented houses had sprung up where you could live in a little more comfort than the old Shebangs they had first lived in. There were still wells but many were shut down because oil was too cheap to pump. Oil Companies had not followed their own advice or any warnings about the financial crush that had already started in the early twenties. Casmalia oil companies were lucky to get 0.65 cents a barrel for crude at the wellhead. Compared to $3.07 in the early twenties this was a disaster for oil companies and Marion and Bruce and their families knew it well. It was the reason for this trip after all.

The price of oil meant gasoline was cheap, about .20 cents a gallon but money itself was losing it’s value. You could buy gasoline for pennies but you couldn’t afford to go anywhere either. The worst time was coming like a fast freight and the price of oil was going to fall even more as the depression deepened. No one can see into the future. My grandparents couldn’t have imagined what they and the country were in for.

They rolled through Santa Maria, crossed the Santa Maria river, dry at this time of year, and over the wooden bridge and the flats of the old Rancho Nipomo onto the mesa planted with, it seemed an endless forest of Eucalyptus trees marching in their perfect straight military rows all the way to the western horizon then down to the sea at Guadalupe beach. Finally cresting the edge of the mesa they rolled down Shannon Hill past the little house where the Shannon’s lived and where my father, future husband of Barbara Hall was finishing up his senior year of High School. They wouldn’t meet for another 13 years.*

Shannon’s 1928. Family Photo

It was a long long trip for the time but because the cars were loaded with what was left of their belongings Grandma and aunt Grace insisted they stay the night at Bruce’s father Sam Hall’s lot on Short street right in Arroyo Grande town. The motor court was just short distance away but money could be saved. There was no house on the lot yet but they said at least staying there no one would think they were “Tractored Out Okies.” In truth they were hardly better off but appearances were important. They had passed the pea pickers camps in Nipomo where Dorthea Lange’s photo of the migrant mother would be taken in a couple years and before they got to Madera they would see many squatters camps and desperate peopled camped on the roadside. You and your neighbor may be equally destitute but al least you have pretense and thats something people hold onto.

Today no one thinks much about traveling in Model T’s. Just another old car, right? Old yes but at the time of this story a modern form of transportation. In old photographs they look pretty large, certainly taller than the average man but compared to your nice SUV pretty small inside. The front seat could barely hold two adults and the rear not much larger. Mechanically they were pretty robust. They were built of steel and could take a great deal of exterior punishment. Someone like my grandfather could fix nearly any part of it. It came with a tool box with a couple of wrenches and you could add a hammer, some baling wire, clevis pins and cotter keys, a piece of leather for the fuel pump if it failed and the odd nail. A tire patching kit which you would definitely need, spare tire(s) jack and a can of lubricating oil. Those things were about all you needed to solve most problems.

Most importantly they didn’t have brakes as we know them. Breaking was done by shifting into low gear. A Model T Ford had only two gears high and low. When got off the gas you shifted into to low gear to slow the car The clutch was actually the primary braking system strange as it may seem today and without too much ado suffice it to say braking was a sort of multi-tasking operation which involved three pedals, the handbrake which was also a gear shifter and two levers on the steering column, one which slowed the motor electrically and the other the throttle. I’ll let you imagine how all this was done simultaneously. It was akin to a circus act and was very dangerous especially on a downgrade. Add some mud or rain and you could become just a large roller skate sliding faster and faster no matter what you did at the wheel.

Shannon hill, on the down hill side was well known in the Arroyo Grande area for the number of deadly wrecks that occurred at the bottom. It’s still there today and is no problem for a modern car. My father who grew up in the little house at the foot of it was well acquainted with racing to the wrecks and pulling damaged people out of those smashed up old cars.**

They chose to travel up the State Highway 1, today’s 101 because the road through Cuyama was still just a two track dirt, unimproved road. There were no gas stations along the way and though it led directly to Taft where he could perhaps find work it was decided to go around by way of the the highway leading east from Paso Robles, today’s Hwy 46. At the time it had no official name. It was a gravel road east of Shandon al the way through the Lost Hills to Blackwells Corners and then due south to Taft where there might be work. Blackwells Corner is, of course famous for the last place James Dean put gas in his little race car. A dubious distinction to say the least. Dean had less than a hour to live until Mister Turnipseed ended him.

The entire trip was notable for the fact that there was nothing that wasn’t tan or brown and usually covered with a fine sandy dust that came from the incessant blast furnace wind so hot that every living thing was in a state of perpetual dryness. The wooden window frames on houses would dry and shrink until it seemed there wasn’t enough newspaper on earth to stuff all the cracks. There was no paint that could stand the heat in the summer and the cold of winter. Dreary isn’t a good enough word to describe those wishful oasis, the end result of a man’s ambition.

Traveling by night out there you might as well have been on Mars. It was so dark out that there was nothing to be seen but the occasional tiny light in the far distance that marked one of the few ranch houses where cattleman desperately tried to scratch out a living on huge ranches which had little water, shade or permanent pasture. Droughts were frequent and devastating and as the depression advanced even those lights would disappear. Sheepherder’s abandoned wagons along the road would be one of the few pieces of evidence that anyone had ever lived among the Russian Thistle.

All along the Kettleman, Lost and Elk Hills from Avenal to McKittrick you could feel the desperation of those that lived there in hard times. Wives ended their own lives by suicide, so desperate for company that taking your own life seemed almost necessary. You could travel fifty miles and see nary a soul. At the end of the twenties it was still a two day trip to buy groceries.

There was no AC of course. You could push the bottom half of the windshield up and lock it if you were desperate for a little cooling breeze but you had to face forward into the blast furnace of wind. No wind wings and the rear windows didn’t roll down. Mom said they would soak a towel in water and wear it around their necks to cool off. Grandpa and uncle Marion were they only drivers and both had bad backs from heavy labor so once in a while Bruce would ask Eileen to hold the wheel and he would get out and walk. The cars were only able to make walking speed going uphill anyway. Mom and aunt Mariel would squeeze out in the space behind the front seats and ride the running boards or lay out over the fenders. Kids weren’t so precious then and could mostly fend for themselves.

Grandpa and grandpa and their children knew it well though for as bad as it was, it was filthy with oil. It was the only reason to live out there and as grandpa once said the whole region was nothing but a “Hellhole.” They had moved from one to another for twenty years and with the coming of hard times in the oil patch perhaps there was some hope that life back on a ranch would be better.

Mom said bouncing along in the back seat with the dust and noise and temperature spiking the thermometer made it the most miserable trip she ever took. She said that while stopped to let the cars cool she was sweating so much, the heat made her dizzy and she put her hands behind her head as girls will do and was fluffing her hair trying to get her neck to cool when she got a look from grandpa who grinned at her, lifted his cap and ran his handkerchief over his shiny bald head and said, “You should have a bald head like me.” That made them both laugh. She surely loved her father.

Give some thought to how it was to ride along on the trip which lasted three days in a car that could only do about 25 MPH on the dirt and gravel roads of the time. Crossing the Kettleman and Lost Hills, speeds were just 4 or 5 miles an hour on the many grades and hang on for dear life on the down hill and all with many stops to top off the radiators and let the motor cool and perhaps add a little oil.

It was all taken in stride though because to my grandparents who were both born before the automobile it was all quite modern and needed no comment or complaint.

Like all siblings the two girls who were barely a year apart fought. “Don’t touch meee, mom he touched me” was a frequent refrain. the girls were sneaky enough but they said the worst was uncle Bob who wasn’t ten yet and liked setting off his sisters. Bruce and Eileen treated this with good humor. Neither one was inclined to fight with their kids and all their children later said their parents never laid a hand on any of them.

When they could they stopped for sodas or fresh fruit from stands along the highways. There is nothing like opening the cooler on the service station porch and dipping your arm into the ice water and fishing around for just the right soda pop. Might stick your face in too. There is also the great pleasure of slipping an ice cube down the back of your brothers shirt.

They were a tight knit little family. They followed the wells and sometimes changed houses or towns as oftenas a month or two. The depended on each other to get by and they remained that way all their lives.***

There was no work in Taft, Maricopa or any of the other fields around what was known as the “Westside.” There were forests of rigs simply sitting idle so they turned east around Buena Vista lake* and headed for Bakersfield and the Kern River fields around Kerndon and Oildale. When you’re on the road headed for a new place spirits rise, things seemed possible, grandpa had worked those fields and knew practically everyone there but again his hopes were dashed. More idle wells, the people he knew had moved on just as he was, scrabbling for a job, families to feed, following the inevitable ups and downs of hope.

Bruce and Marion wheeled the two Fords out onto highway 99 and headed north up the valley. Money dwindling, hope lying exhausted on the floors of the cars and the kids tired and cranky the families rolled up the finest highway in California. Completely paved, the 99 was easy driving as they passed through all those little towns that sing a song of Californias agricultural heritage, Famoso, Delano, Tipton to Tulare, Kingsburg and Fowler to Fresno, click, clack the hard rubber tires tapping out a tune of the road as they bumped over the joints in the concrete roadway. After Fresno it was back to the old home, The house where my mother was born in 1918, just 23 miles more.

* This link below will take you to the story of how Barbara met George. The Milkman in four parts.

https://atthetable2015.wordpress.com/wp-admin/post.php?post=5632&action=edit

**Family letters, link below.

**File under Grief, link Below

***Family letters, link below.

Michael Shannon is busy telling the story of his California family.