Come the Little Giant.

Michael Shannon

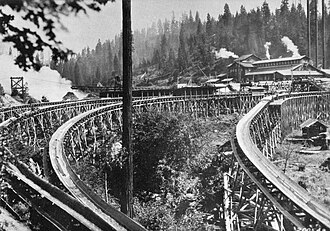

Madera, California. Madera was founded in 1876 as a lumber town at the terminus of a flume built by the California Lumber Company. The town’s name, meaning “wood” in Spanish, reflected the timber industry that spurred its growth. But if you were looking for a job in the mills you could forget that. The Depression ultimately brought an end to the lumber era. A collapsing market for wood forced the Madera Sugar Pine Company to cut its last log in 1931, and the mountain sawmill closed shortly thereafter. The marvelous 63 mill long flume from the mountain mill to the planing mill in Madera went dry. By 1933, the company’s assets were liquidated, marking the end of nearly six decades of logging that had been the foundation of Madera’s economy.

When the timber industry died, agriculture emerged as Madera’s primary business. Farming had already begun in the late 19th century, with irrigation from the San Joaquin River boosting crop production. The 1930s marked a significant shift from sawmills to farms. Unemployed lumbermen and mill workers left for more likely places and were replaced by migrant farmworkers, including many Dust Bowl refugees, who found seasonal work the fields and orchards which now dominated the economy.

The big cattle ranches who grew their own feed were being squeezed out by the terrible drop in meat prices and consumption. There was so little cowboying to be done that they got off their horses and began working the stockyards and packing plants. Most of th the big ranchers failed and the land was sold or just abandoned for unpaid taxes.

Henry Miller a former San Francisco butcher began buying land in the central valley. Miller built up a thriving butcher business in San Francisco, later going into partnership with Charles Lux, a former competitor, in 1858. The Miller and Lux company expanded rapidly, shifting emphasis from meat products to cattle raising, and soon became the largest producer of cattle in California and one of the largest landowners in the United States, owning 1,400,000 acres directly and controlling nearly 22,000 square miles of cattle and farm land in California, Nevada, and Oregon. Madera was smack dab in the middle of the Miller and Lux holdings and Henry Miller was ruthless in controlling not only the land he owned by any adjacent properties. He also used bribery especially keeping tax assessors and town officials in line. Miller and Lux also became owners of the lakebed of the Buena Vista Lake. Miller played a major role in the development of much of the San Joaquin Valley during the late 19th century and early 20th century. His role in maintaining and managing his corporate farming empire illustrates the growing trend of industrial barons during the Gilded Age.

Bruce and Marion were aware of the terrors associated with industrial operations in the oil fields. Keep wages as low as possible provide nothing but temporary and work keep the unions a bay. Company loyalty only went one way, up. After more than ten years in the wells Bruce had thought that he would be protected by his superiors but with Barnsdall closing down it’s wells in Santa Barbara and literally sneaking out of town and back to Texas both men were left adrift. By the middle of 1930 there were a dozen or more men for every job. Having to retreat to Madera took them far away from the areas that were still operating.

Looking for work by telephone was frustrating. How many times did he spin the crank on the old wall phone and try to contact some one from the rumpled list of operators, contractors and owners taped to the wall in the farm house kitchen with pieces of yellowing Scotch Tape.

“Bruce, we might have something coming up in a couple months if the big boss can rustle up some financing so we can afford to drill, but I don’t know. Wyncha give me your number and I’ll call ya if sumpin breaks.”

They tried driving down the 130 miles to Bakersfield and the westside around Taft but that turned out be just a waste of gasoline.

So it was back to farming. They worked the ranch for grandpa Sam Hall and hired out for the various harvest seasons. Spending days climbing ladders to pick Apricots, working the Walnut orchards and the nut processing plants. There was a vast amount of cotton to hand pick too. They got by.

People had to eat no matter how poor they might be so agriculture stumbled ahead. My dad said that during the depressions farmers didn’t starve in California. My family in Arroyo Grande had a dairy, kept pigs, chickens and a goat. They grew their own feed and he said the old fashioned barter system kept them in vegetables which people traded for milk. They traded beef with the butcher Paul Wilkinson instead of cash. Milk was good for bread at the bakery and my grandmother’s little bag of coin which she got from her milk deliveries was enough for the Commercial Market. He said it was rough but everybody got by unlike people in the cities and industrial areas. He said people got used to having less, they didn’t travel as much and simply entertained themselves with local theaters and the goings on at schools and picnics put on by the lodges and clubs. He siad the the community was closer and better of for it.

Bruce, Eileen and the kids muddled on. Madera was a good place to live. There was swimming in the river with their cousin Don Williams though for some odd reason neither my mother or my aunt Mariel ever learned to swim but there were boys there and they were just getting to that age. There are few things better than lazying about a slow moving California River on a frying hot and dusty day. Slathered in baby lotion and olive oil, Mariel and mom would lie in the cool water slipping down from the high Sierra and bake.

And bake it was. The San Joaquin valley is a hot place in the summer. In old farmhouses built out on the flat ground west of the foothills of the Sierra Nevada where the land acts like a mirror radiating the heat like a flatiron. Kids who ran barefoot had to sprint from shade three to shade tree to keep from burning their feet. The old Hall ranch house was a single wall place, no such thing as insulation unless you counted the folded newspapers stuffed in the spaces between the vertical sugar pine boards that held it up. AC was not even a dream yet. At night they would open the sash windows to hopefully cool the inside a bit and in the morning close all the blinds to try and keep the night’s cooler air from escaping. “Close the door” was the call, trying to get the kids to close the door as they went in and out on their endless imaginary errands. Mom said they hauled the mattresses outside onto the porch to sleep at night if they could. Their sheets were soaked in water when it was unbearably hot. In July and August temperatures at the metal Coca Cola thermometer nailed to the wall out on the covered porch hit over 100 degrees every single day. It was cooler at night, somewhere in the seventies but that wasn’t til long after dark.

Bruce, Marion and grandpa Sam Hall would sit out on the covered porch as the air cooled, smoking drinking and talking about the days affairs and the state of the country and oil in particular. Passing a pint around the talked about the terrible bog the industry was mired in and not only the oil business but the entire western world. They wouldn’t have known it then but it would go down in history as the worst economic depression ever recorded. Breadlines and soup kitchens were already forming in California, there was even one on Yosemite Avenue in downtown Madera. Unemployed men, many from the the professions or fresh out of college were forced to live in “Hoovervilles,” gatherings of shacks, tents and cars while they desperately looked for work of any kind. Migrant workers and their families began swarming into the Milk and honey mirage that was California to escape the dust bowl and failing cities of the east. Highway 99 was seeing a massive caravan of the hopeful and desperate heading north and south looking for work. It was nothing less than a tidal wave of the unfortunate flooding the state and willing to take any kind of employment.

Banks and business firms were closing their doors. Runs on banks by people desperate to withdraw what money they had caused bank runs all over the country. Nine thousand bank failed. With no reserves a bank could not lend money or earn money. Farmers were defaulting on the annual loans, business firm too. Many banks instituted foreclosures against oil businesses, the fear this caused in the highly speculative business sent companies running for cover.

The smaller independent oil companies were the hardest hit. Hundreds in California simply disappeared, walking away and leaving wells half drilled or simply capped. The majors just quit drilling altogether. The price of gasoline hit .09 cents a gallon in 1930, less than the cost to bring in and put a well online. It would get worse.

For Bruce and uncle Marion it was hard to see a way out. Bruce Hall was just thirty five years old with a wife and three children and what seemed the bleakest of prospects. The burden must have been nearly impossible to bear, but bear it he must.

The phone rang. It was two longs and a short, the Hall distinctive ring. Thats the way it was on the old party lines. Aunt Grace got up from the table where she was peeling peaches for pie, wiped her hands on her apron and lifted the receiver and put it to her ear, “Hello,” she said. “Yes this is the Hall residence, Bruce Hall? Yes he lives here, can I ask who’s calling?”

“My name is O. P. Yowell, Bruce knows me as “Happy, Is he around, they gave me this number to call at the office.”

“Why yes he is here, he’s down in the orchard. I can send someone to fetch him if you can wait a few minutes.”

“That would be fine Mrs. Hall, I’ll hold.”

Aunt Grace looked over her shoulder for the nearest available kid and spotting Barbara playing solitaire she said “Barb, can you run down to the orchard and tell your father he has a call. Tell him it’s a man named Happy.” She winked at her niece, “a man named Happy, how about that.”

She turned back to the phone and asked what the call was about then said “O K, I understand. It will be just a minute”

Barbara, she yelled as she heard the screen door slam, “Tell your father it’s a man called Happy from Signal Oil, he says that Sam Mosher wants to talk to you.”

“And hurry honey, It’s important.

Michael Shannon is surfer, teacher and World Citizen. He writes so his children will know where they came from.