Chapter 15

The Desperados

By Michael Shannon

Grandpa called Grandma from the phone in the Signal office on Orizaba Street. He gave her good news. She especially liked the idea of going back to Santa Barbara. As was the custom with them she started getting all that the little family would be taking with them together. Clothes for the girls and Bob, toiletries and whatnots, just what could be packed in a suitcase. The kids carried their own. My mother was twelve and Mariel thirteen. Bob had just turned ten so whatever they could carry was what they took. Moms piano and a little furniture would have to be shipped later. Uncle Marion would drive them down by the same route they had gone up to Madera. Marion was counting on Bruce to put him on a crew so it seemed like a good bet.

Following the work was the name of the game then just as it is today. My mother said it was normal for kids who had never known any other way. They kids knew how to make new friends and were all sociable at that age. It would never change as they grew.

Grandma could shake and bake. Get ’em packed, sacked and on the road. Rent a house, bring the goods and move ’em in. Enroll in school, do it in jig time too.

733 East Islay St, Santa Barbara. The 1930, Home to the Hall’s, Zillow photo

She had the whole thing down to a science. Grandpa would come home from work or get a phone call telling him he had to be at another rig the next day or two and he would leave right away, Eileen and the kids would follow. The house shown above was their home after arriving from Madera in 1930.

Sam Mosher had a specific purpose in mind when he hired Bruce. Whipstocking. Although the Ellwood field was already operating he had bought some abandoned and unproved leases at the very edge of the Ellwood field.

Other companies geologists had determined there was no oil to be had. It was a big gamble for a small operator but the leases were cheap and his geologist thought that there were oil deposits if they went just a bit deeper. There was also a possibility that the so-called safe lease would be a total disaster. One thing about Sam Mosher, he was not risk averse.

Mosher who was born in Pasadena in in 1892, just three years younger than my grandfather. His father sent him to the University of California at Berkekly where he earned a BS in Agriculture. Right out of university he leased and began farming seventeen acres of Lemons and Avocados in Pico Rivera. In 1918 all of what is now western Los Angeles was farmland with a few small towns dotted about. It was a struggle and Sam worked sixty to seventy hours a week and then used his Ford tractor to plow and disc for other farmers near by. He always said afterward that he “Didn’t know a darn thing about oil wells or the business.

A single event changed all that. On June 23rd, 1921, a wildcat well on the lower slope of Signal Hill announced itself with a massive plume of crude oil. Coming in with a roar like the passing of a steam locomotive and the unbelievable shaking and rumbling of an earthquake, Alamitos no. 1 borned itself and set off the mad scramble for discovery on what became the richest field ever found.*

A drifting fog of micro dots of oil spread eastward on the back of the northwest ocean breeze, depositing crude on every surface. Clothesline’s, cars in the driveway and the houses themselves soon were coated with the sticky black residue of decomposed plant life from a tropical earth gone away millions of years ago.

Bumper to bumper lines of cars from Los Angeles came out to see the well. It was an event that would grow the city in ways none anticipated. The 25 miles to Signal Hill were dotted with small towns and orchards like Mosher’s in Pico Rivera. Looking up from his tractor’s seat, Sam Mosher couldn’t have helped thinking that the drudgery of farming could be traded for riches from the oil patch.

Alamitos number one set off a frenzy of drilling that within a few years saw wells in the Dominguez Hills, Torrance, Santa Fe Springs, Long Beach, Belmont shores, Seal Beach, The Bolsa Chica and Huntington Beach. Bruce would work them all.

The Halls were getting settled in Santa Barbara, kids enrolled in school and Bruce was back at work. Lucky for them too. Because of the depression unemployment was pushing 25%. There was no unemployment insurance or Federal minimum wage and hordes of desperate men and boys, women too, hopped the side door pullmans as they rattled back and forth across the country. Midwest farmers abandoned their farms because if you could find a bank to loan you “Crop Money” the crop itself would, more than likely not sell for enough to pay off the loan. More farms abandoned or foreclosed every week. Banks failed because there was no FDIC to guarantee money to keep them solvent. Factories cut wages to the bone, seeing it as the only way to turn a profit. In many cases it just didn’t work. More families took to the road than ever before in our history searching for work, just something to put food on the tables. The government of president Hoover blamed it on the workers. “They are Communists, Unionists, Fascists, they don’t want to work” he said. Sound familiar?

The Knight Riders, the Ku Klux Klan which had existed in the old Confederacy rose up from its deathbed and reappeared all across the county. Burning, looting and lynchings occurred for the first time in decades. Their target, Blacks, immigrants, Jews and unionists. The government did very little to stop it. The FBI focused it’s energies on these same people as Hoover acted as an enforcer for the wealthy entrenched establishment.

Business, finance, the law and government acted as if it was business as usual. unable or unwilling to do anything except support the status quo. Hoover, promising “A chicken in every pot” was one of the more callous election promises ever made in this country. He couldn’t produce the promise and wouldn’t seriously try. The callousness of the sitting government was focus on protecting those that had and not those that didn’t. It would cost him the Presidency in 1932.

The Oil Patch was no different, wages were sinking, drilling was slowing dramatically. With car sales plummeting no one needed the gasoline no matter how cheap. Every one in oil production understood this but at first they could not slow down. Pure greed, especially by the big companies like Standard, Sinclair, Richfield who could only survive by drilling held sway. When it got to the point where high production was unsustainable they cut costs to the point where the independents were forced to quit, putting thousands of roughnecks, toolies and supers on the road with laid the off factory workers, tractored out farmers and small business failures.

Everyone went from unbridled optimism, where no amount of oil seemed too much to the point where wells were simply pumping it into earthen pits waiting for a price hike and when they didn’t come, they walking away from their wells. In many cases no one bothered to even plug the casings leaving the well heads wide open.

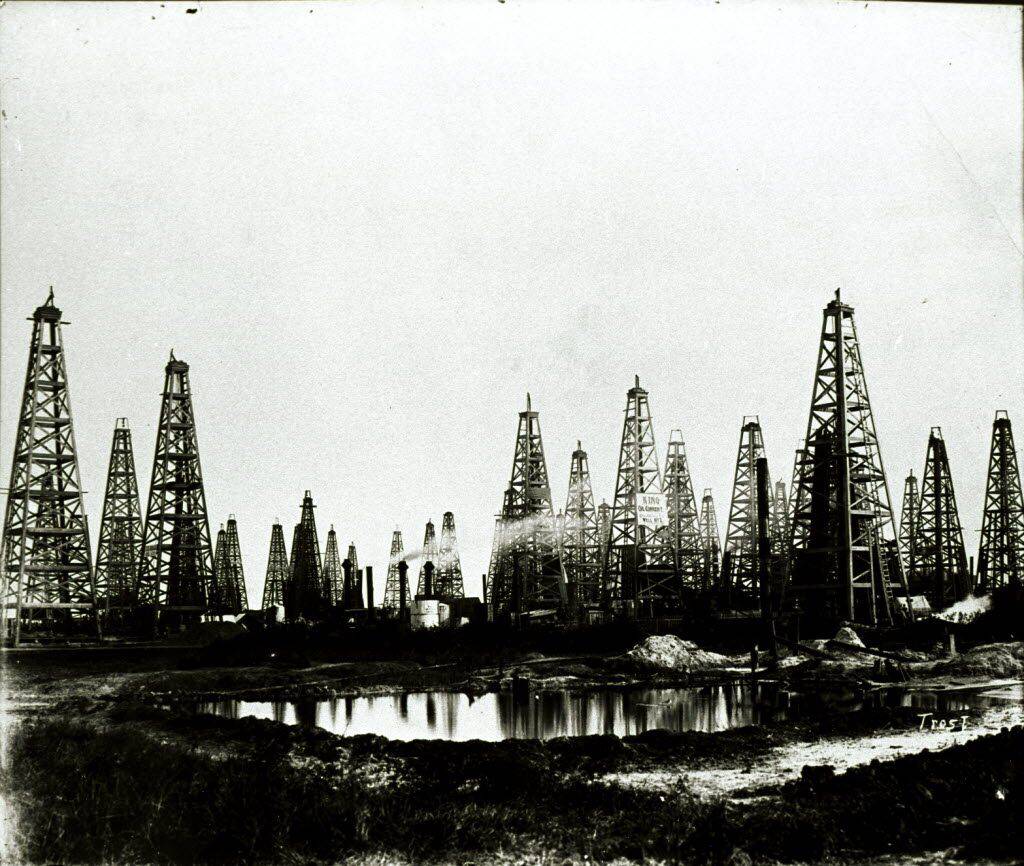

An oil sump, Signal Hill, 1930. Long Beach Historical Society

The land owners who had leased their mineral rights to oil companies took it in the shorts too. Your little farm where you had some fruit trees an a few acres of vegetables were suddenly covered in waste oil, abandoned machinery, derricks and muddy roads everywhere. The trees were long dead, the house coated in oil mist and you never saw a dime from your share of production. You were abandoned too.

So, fortunate Bruce was. After twelve years traveling the state chasing crude you at least had a job with a small company which was hell bent on surviving by taking on the riskiest of projects on the chance that they might, could, or would pay off. Sam Mosher had given up the lease on his little seventeen acres of fruit trees in Pico Rivera so for him it was do or die.

With some Signal stock and promise of a piece of production for capital he didn’t have he bought a lease north of Elwood, near Goleta that had never been “Proved.” At what geologists thought was the end of the underground pool at Elwood, he bought from a local attorney in Santa Barbara who had leased some ranch land right at the foot of the tidal bluff just north of Tecolote canyon. The attorney had no luck and wasn’t able to find anyone who would even contract to drill there.

Though Geologists at the time had more than a century of practical experience in finding oil the devices used today where nonexistent in 1930. They looked for areas where surface indications showed the presence of undersea creatures. Fossils, like Trilobites on the surface especially on a hill or hills called Anticlines** sometimes indicated oil pools below. Ancient seabeds where plant life once flourished turned out to be where you could get rich drilling. The San Jaoquin Valley and the southern coastal regions of California had massive oil pools if you could find them.

We have a box of prehistoric sharks teeth that grandpa Bruce collected from the many leases he worked, mostly from the Elk Hills which runs along the valley’s westside. He would come home and thrill his children with tales of an ancient world where enormous sharks patrolled a sea which was now dry and dusty hills baking in the San Jaoquin valley’s brutal summer heat. My mother kept the teeth all of her life and the little box now resides in a drawer of the desk I’m writing this story on.

In the get rich quick culture of the oil business, landsmen would go out to areas where oil was discovered or about to be and for a fee or a promise of a percentage of production for a specified time the underground rights to said property were purchased. This meant that the oilman could drill on the property and if they found enough oil and it was worth producing, they would kick back to the actual owner of the land a specified percentage of sales. Leases on Signal Hill were sometimes negotiated by the square foot and even, in a few instances, by the square inch. How anyone could understand this complex and inherently crooked system is anyones guess. Of course that was a win for the oil men and their lawyers.

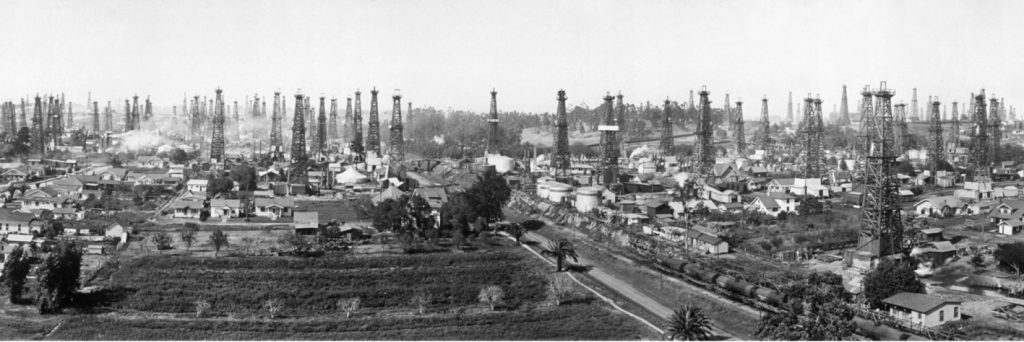

There were almost no rules. Oil companies with sharp lawyers and accountants ran roughshod over property owners all the time. Getting the right to drill without any up front money was the key for the Landsmen and many an owner ended up with his lot trashed, steeped in waste and marked with an abandoned wooden derrick as tall as 82′ feet looming over his house. An absolute frenzy occurred every time their was a big strike. On Signal hill and the west Los Angeles fields most of the leases were on standard house lots. Each lot might be a different wildcatter. Some derricks on the hill were so close together that their legs were intertwined. Drill stings became entangled hundreds of feet underground with one company drilling right through the pipe and casing of another. It was fertile ground for lawyers. Fertile ground for roughnecks too who went to war with their neighbors, fists, pipe, ball bats and six shooters were not uncommon and close to hand.

Signal Hill, east Willow street, California 1930. Calisphere.

Property owners were basically ignorant of the actual doings of companies. Fast talking lease buyers, shifty drillers and sharp lawyers could end up, through slight of hand, leaving the poor small farmer householder holding the bag. There was a property owner in Long Beach who told his friend at the barbershop that he was no fool, “That danged lease man offered me 10 points of the profits, but I ain’t nobody’s fool I’m holding out for a 20th.” He was getting more than one shave he just didn’t know it yet.

Mosher and his company signed the documents for the lease in Goleta but in so doing apparently no one read the docs very carefully. Under California the law at the time a leaseholder had 12 months to “prove” a lease by beginning drilling before time ran out. After signing the documents a sharp eyed engineer noted that all but 28 days of the year had gone by. Signal had just 28 days in which to prove the lease on a piece of property with no access, no road and at the foot of a steep bluff that ran down to the hight tide mark. To make matters worse they would have to seek permission to cross the tracks of the Southern Pacific RR tracks which meant red tape that could take a year or more. The Southern Pacific was once known as the Octopus and for good reason. There was no doubt on Orizaba street that they would do just that, squeeze as much out of Signal as they could.

It would seem to be a lost cause. Mosher sent his Varsity Team a he called it, the first gathering of the young experts he had hired at Signal to scout out ways to to spud in a well before the 28 days ran out. There was no road down to the beach just a brush choked gully. Maybe an access road could be bulldozed down it to get equipment in but there was no way to cross the RR tracks legally. No dozer, no road, no road, no steam shovel to cut down to the beach, checkmate. The property owner keeps the payment and Sam Mosher takes it in the shorts as the old saying goes.

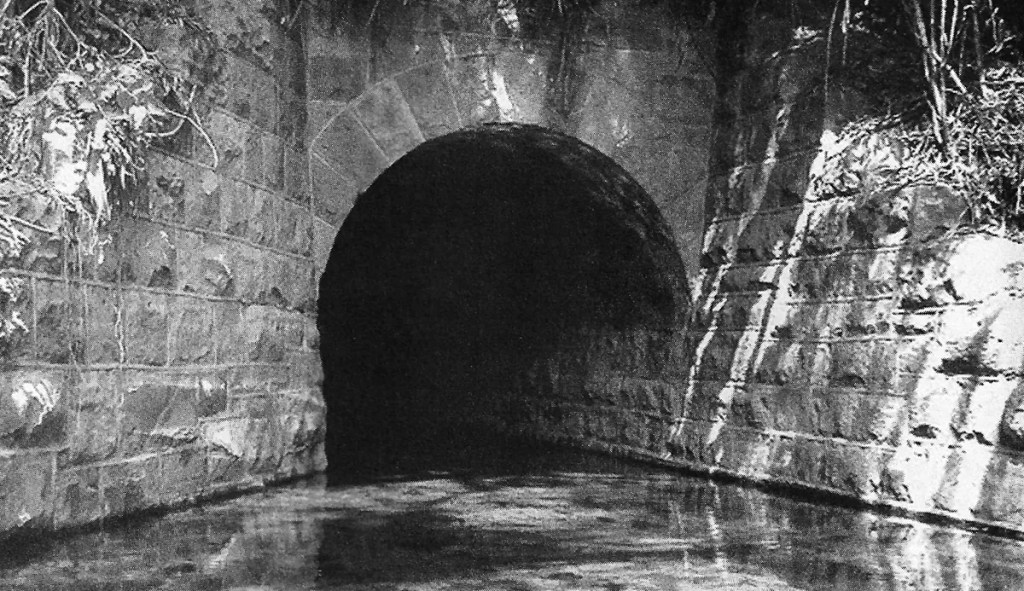

After a couple days of nosing around one of the engineers walking the track had to cross a gully alongside the tracks and found back in the brush, a stone culvert the SP had built in order to throw the track across the ravine which was active in the winter and couldn’t be blocked. He looked over, scrambled down the slope to the creek bottom, took out his measuring tape did a few calculations and then high tailed it back to Goleta and called Orizaba street and talked to Garth Young, Mosher’s young, chief engineer.

“Garth, I found a way in where we don’t have to get permission from the railroad. I figure our shovel will just fit with about five inches to spare, we can just drive her in.”

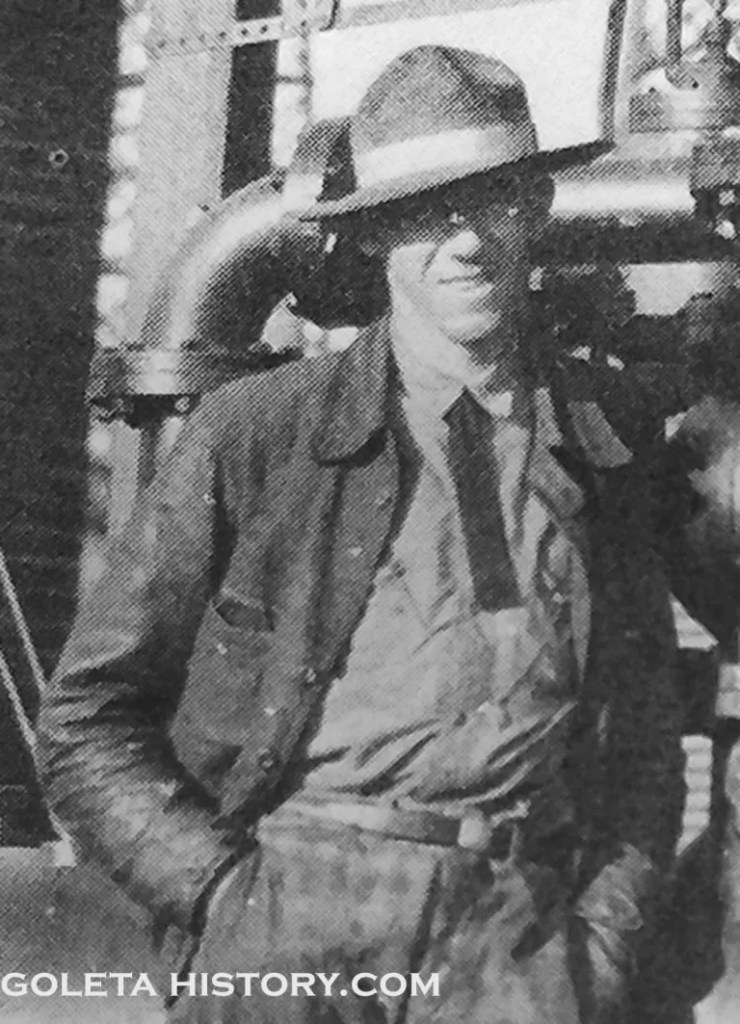

Sam Mosher and Garth Young. 1930. Signal Oil Company photos.

Young replied, “Well we can’t do that it’s still railroad property and we have to have permission.”

“Hell with the railroad Garth, let’s just do it and deal with them later. What are they going to do after its done, sue us?”

“Probably, but what the hell lets just go ahead. Our times running out and we need the well or it’s all lost anyway.”

“OK boss, we’ll roll the shovel up tonight and we’ll be down to the bluff before sunlight. Those railroad stiffs will never know.” Getting permission from the railroad to pass through this culvert would have also held them up, so Garth Young decided to do it without telling his boss, relieving Mosher of any personal responsibility.

Mosher had already gotten permission to pass through the Eagle Canyon Ranch from the owner, Louis Dreyfus, while his Engineer, Garth Young’s boys had discovered a passageway to the shore.

The Culvert on Eagle Canyon. Goleta Historical photo.

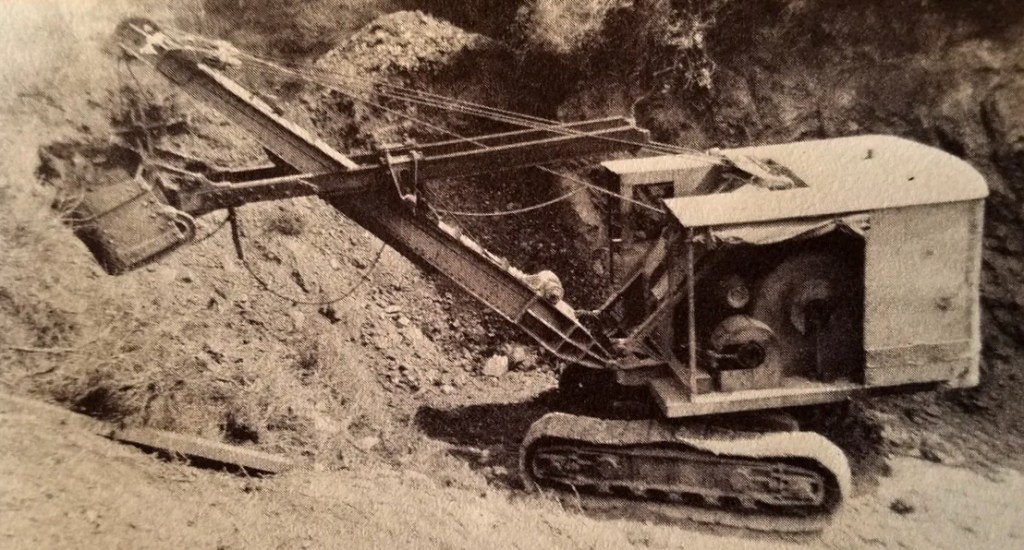

The heavy-duty self propelled power shovel made its way through the dry Eagle Canyon creek bed. As it approached the culvert, the operator lowered the boom to horizontal, the huge clamshell shovel blades mere inches off the ground. The prehistoric looking iron beast slowly crept through the dark stone tunnel, foot by foot, as Garth Young watched in suspense. Without a hitch, the giant piece of machinery clanking and squealing crawled carefully through the dark tunnel and emerged into the dark of midnight. Walking alongside with flashlights they maneuvered the iron monster down the dry creek bed and onto a shelf above the driftwood littered beach.

Taking the first bite of the bluff. 1929. Goleta Historical Society.

Time to go to work. Times running out. Young explained to the operator that he would have to wait for the tide to go out, then clear a way down the beach to the foot of the cliff below Hydrocarbon Gulch. He would quickly dig a foothold at the base of the cliff before the tide comes back up. If he didn’t his shovel would sink into the wet sand and the job would be over. The driver laughed at the crazy plan and said it would likely take him 10 days. He would drive back to the culvert every high tide and return on the next low. But Garth Young told him they didn’t have 10 days, it needed to be done, and done today. And if he didn’t succeed, they had insurance for the power shovel anyway. No problem there except they, had no insurance which was a bit of a necessary fabrication as Garth saw it. If they lost the shovel it was a moot point anyway….

*The Long Beach Oil Field is a large oil field underneath the cities of Long Beach and Signal Hill, California, in the United States. Discovered in 1921, the field was enormously productive in the 1920s, with hundreds of oil derricks covering Signal Hill and adjacent parts of Long Beach; largely due to the huge output of this field. The Los Angeles Basin produced one-fifth of the nation’s oil supply during the early 1920s. In 1923 alone the field produced over 68 million barrels of oil, and in barrels produced by surface area, the field was the world’s richest. During the early stages of the field’s development, unlike most oil fields, land was leased by the square inch instead of by the acre. The field is eighth-largest by cumulative production in California, and although now largely depleted, still officially retains around 5 million barrels of recoverable oil and has produced 963 million out of 3,600 million barrels of original oil in place. 294 wells remained in operation as of the beginning of 2008, and in 2008 the field reported production of over 1.5 million barrels of oil. The field is currently run entirely by small independent oil companies, with the largest operator in 2009 being Signal Hill Petroleum, Inc. Sam Mosher’s old company.

**An anticline is simply the opposite of a decline, meaning a geographic feature characterized by a geological fold in rock strata where the layers bend upwards, forming a convex shape, resembling an arch or an inverted “U”. It’s the opposite of a syncline, which is a downward fold. Anticlines often form due to compressional forces that cause rocks to bend and buckle rather than break. In oil fields the fold is created by the upward and immense pressure from the gas created by the decomposition of vegetation underground. It’s important to know that not every hill overlies and oil field hence the often used word “Lucky” applied to wildcatters.

Michael Shannon is a grandson of Bruce and Eileen Hall. The life of oilmen was a serious topic when he was growing up and listening to his mother’s stories about growing up in the oil patch. He writes so his children will know where they came from and who they are.

A Notice to the Reader.

For those of you who read this Blog on the Facebook platform I’d like to explain some changes that are affecting your ability to read and see them. Many FB sites have gone to AI to do the work of administering who gets seen and who doesn’t. This means that there is no actual human being deciding who gets published and who doesn’t. Programmers have designed algorithms to filter submissions to all kinds of platforms. What this means to me is that about a month ago quite suddenly a dozen or so FB sites that I published on suddenly began refusing my content, all of it.

I have been unable to find out why or actually speak to a real human person as to the cause. What this means to me is that though I reach over 50 countries through the WordPress platform I’m reaching only those that are on my friends list on Facebook. Readership has plunged from hundreds per post to around a dozen on a good day.

I believe that soon AI will rule FB entirely and the “Social” will no longer be attached to the Media.

I encourage you to go to https://atthetable2015.com/ and click the follow button. When an article is published you will receive a notice in your email which you can click to open and read.

For those who are curious, there is no profit for me in this. It’s free to you and I receive nothing other than your goodwill.