Chapter 18

The Big Shake

Michael Shannon

“Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On.” Out in California shakin’ is a fact of life. If you live here long enough your going to be in one. People can date their lives, just like reading a clock. Which one did you ride out. Was it the Great Fort Tejon in 1857, the Hayward in 1868, or Santa Barbara in 1927. California recorded 9 severe to catastrophic quakes between 1900 and 1933. My grandfather Shannon and his wife to be Annie Gray rode out the San Francisco in 1906 which they never forgot and over time they generated dozens of stories. It went, in the telling, from a catastrophe to legendary status in our family.

Family histories are bookmarked with these. Time, day and place vividly recalled.

Call Newspaper tower on Market Street in flames, April 18, 1906. Hearst photo.

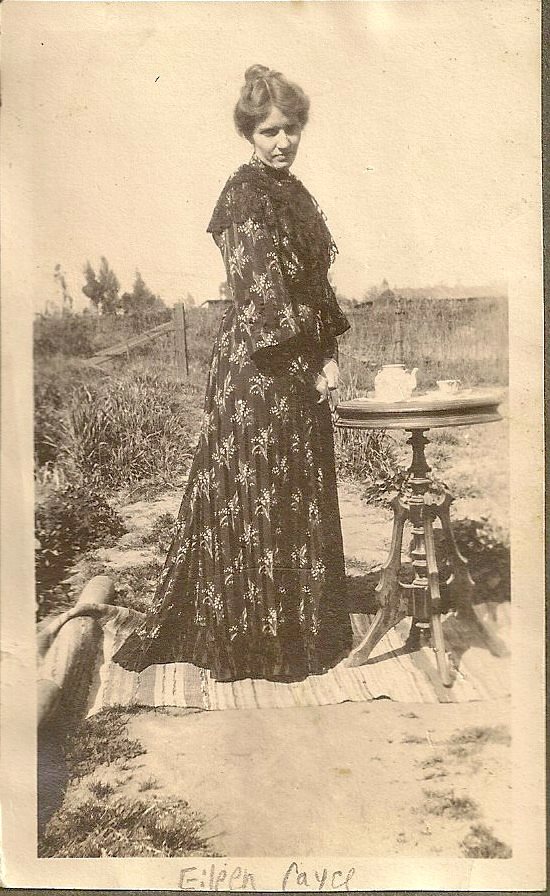

In 1933 Eileen was nearing her term. In a mark of the times she would deliver in a hospital. This child would be the first in the family not born at home. No midwife, no husband or sister-in-law, no mother-in-law. What could be safer or more modern?

Eileen was checked in Cottage Hospital in Santa Barbara. Built in the Spanish Colonial style it was to be a new and unique experience for Bruce and Eileen and baby to be.

Santa Barbaras Cottage Hospital, 1930. News Press photo.

Delivering a baby at 38 was a dicey proposition in 1933. There had been many improvements in in pre-natal care in Eileens lifetime, infant death rates had dropped significantly since 1900. The diminished numbers of home births was a major contributor along with the acceptance of theories on anti-sepsis and the rise of hospital culture.

In 1888, a group of 50 prominent Santa Barbara women recognized it was time for the growing community to have a hospital — a not-for-profit facility dedicated to the well-being and good health of all residents, regardless of one’s ability to pay or ethnic background. It was a major milestone in the communities history as the population was just five thousand people when the little 25 bed facility opened its doors in 1891.

In ’33 Bruce had a steady job but his pay could barely cover expenses. The depression had reached its lowest point for American people. March 1933 saw the highest number of unemployed, estimated at around 15.5 million. Those numbers represented just under 25% of the workforce. New Mexico jobless numbers were pushing 40%, the highest in the nation. For those who were lucky enough to keep their jobs, wage income had fallen 42.5% between 1929 and 1933. The country had no social security system, no unemployment insurance the unemployed had to rely on themselves and the overwhelmed relief agencies. People resorted to desperate measures to find work or earn money, such as waiting for a day’s wage or selling goods on the street. Children were turned out of their homes to fend for themselves. There was a great deal of unrest across the country.

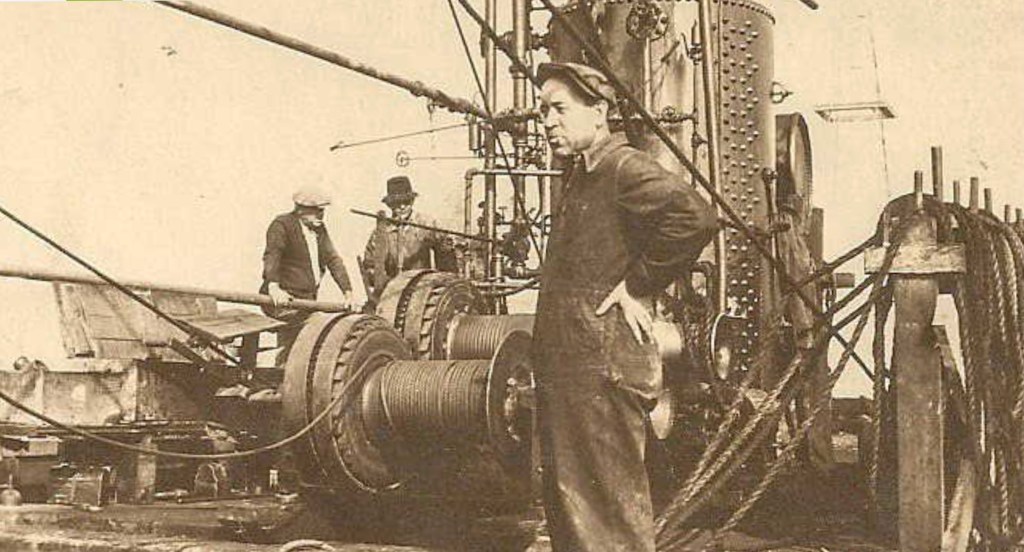

In San Francisco, the hiring of day laborers called a “Shape up” in which those chosen from a crowd of the hopeful were employed for just a day rather than long term led to the violence of the 1934 West Coast Waterfront Strike, particularly the events of “Bloody Thursday” on July 5, 1934. During Bloody Thursday, San Francisco police open fire on striking longshoremen, resulting in the deaths of two strikers and hundreds of injuries. This escalated the strike into a citywide general strike, where over 100,000 workers in solidarity with the longshoremen walked out and shut the city down.

The majority of the population in the country were bordering on frantic, not knowing where the next meal would come from or how and where they might live.

The Halls had three teenaged children who needed to be clothed and fed. They lived in a small rented house and were by some slight miracle were just getting by. Timing for the new baby couldn’t have been worse.

Not just bad timing either. Eileen had nearly bled to death when Bob was born in 1920. Only aunt Grace’s sprint into Orcutt for the doctor had saved her life. She was very weak for months afterword. Bruce and Eileen told each other that there could not be anymore babies. It was much much too dangerous. The thing is, nature will find a way and it did.

Though the first human to human transfusion was successfully done in 1818 the classification of blood types was only codified in 1900. WWI led to the first mass use of the life saving procedure. Like most things the ability to do a transfusion became routine but the underlying structure which provided the actual blood was not. Blood could not be stored for long periods of time, just days in the best of circumstances. It wasn’t until that the first blood bank was established in a Leningrad, Russia hospital. National organizations did not exist. The first was by Bernard Fantus, director of therapeutics at the Cook County Hospital in Chicago, established the first hospital blood bank in the United States in 1937. In creating a hospital laboratory that can preserve and store donor blood, Fantus originates the term “blood bank.” Within a few years, hospital and community blood banks begin to be established across the United States. It was much too late for Eileen as Santa Barbara had only a very small supply of whole blood on hand in March of ’33 .

Not only is childbirth for most women life threatening but in 1920 when Bob was born the chances of finding blood for a transfusion were unlikely. The doctor ran his small practice in an office above a little shoemakers shop in Orcutt and had no way to store blood of any type. The fact that he was able to get to the lease and find and tie off the bleeder in time was a miracle. The lack of transfusion was the main reason for her long recovery.

If Eileen were to hemorrhage she could well die and her doctor in Santa Barbara insisted she deliver at Cottage. They had no money to pay so Eileen went down to the welfare, they called it relief then and applied for help to pay the hospital. They gave her such a hard time that she felt ashamed that they though she was just another chiseler. She went home in tears and told Bruce that in order to qualify they would have to sell the car which he needed to go to work.*

She told the doctor that they had decided that the baby would be born at home just as the others were. The doctor was adamant and said, he and some other doctors had gotten together and agreed to get together and take care of people who were in need and that the hospital had established a fund for the same reason.

“Eileen, you will be treated the same as if you lived in Montecito with the rich folks.” He said, “No one will ever know.”

Perhaps the sun was about to break out.

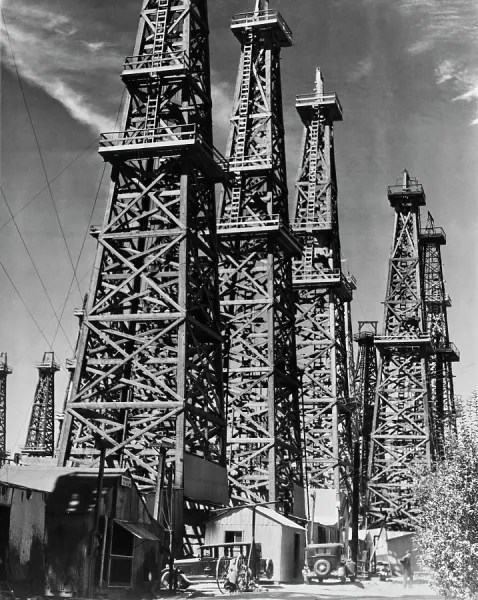

They were in Santa Barbara after the layoff and then bankruptcy of Barnsdhal oil. There were no oil field jobs in the Los Angeles basin, absolutely none. They had bought a small house in Wilmington near Bruce’s brother Bill and his wife Anna. When Bruce lost his job and couldn’t find a new one they called Eileen’s brother Henry Cayce who lived with his wife Martha and their three kids in Goleta. Henry had a good job as a mechanic and in the way of family they said come on up, we’ll find room for you all.

So the house in Wilmington was lost, the first they ever owned but they couldn’t make the payments so they turned in the keys and just walked away as so many others did during the depression. By late 1932 it was being called the great depression because there was no doubt that it was the one.

They closed and locked the door for the last time, loaded their suitcases and whatever they could carry, drove to the filling station, gassed her up and they still had .50 cents left. Always responsible and money conscious but with nothing to lose, they said “To hell with it and went to the movies.” They saw “Tarzan the Ape Man” with Johnny Weissmuller and Maureen O’Hara. When it was over they took their popcorn and dead broke, hopped in the car and headed to Santa Barbara. They had this way about them where they looked on life as if it was a big adventure. They would do their best, come what may.

At Henry and Martha’s Bruce got up the next day and went looking for work. There wasn’t any possible way that he would find work in the oil fields so anything would do. At thirty eight half of his working life had been in oil and though it was rough it was all highly technical and built almost entirely on experience. He could not read a book on how to do the work. It was learn by doing. All of that seemed out the window now.

Steinbeck’s story about the Joad family would not be published until 1939 but the reality of it was being played out across America every day. The novel explores themes of social injustice, economic hardship, the loss of the American Dream. The power of community and collective action in the face of suffering was for the Hall’s, the way out.

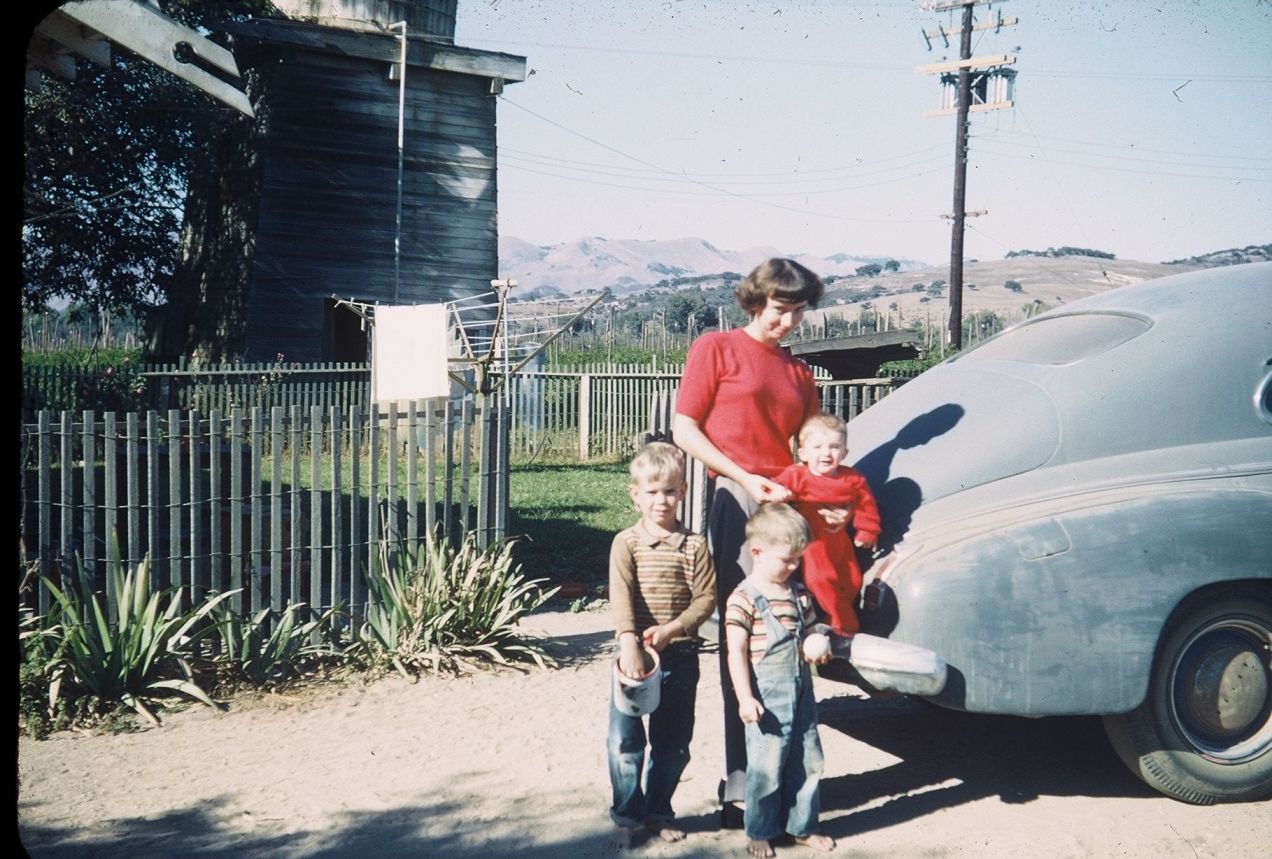

Henry Cayce was Eileen’s uncle and by coincidence an oil worker. He had worked for Barnsdal in Elwood as a mechanic but had also lost his job. He now worked as a garage mechanic in Santa Barbara. They rented a big house in Hope Ranch and had three kids of their own which made six at home. Eileen ran the house and took care of the kids and Martha worked in her mother’s little grocery store. The house was in a walnut grove so Eileen and the six kids shucked walnuts and sold them downtown for extra money. They did whatever they could find.

Bruce took any kind of job he could find mostly doing day labor. A few hours here and a few there most not lasting very long and bringing in a little money to keep them going. He finally got on a a garbage man, humping trash all day. His bad back was murder, but it was life or death, up at four and home at four. He continued looking for oil field work. Call after call hoping that something would turn up. My mother said, she was going on fourteen, at the time that she really didn’t know much about that part of her life just that it was fun to be with her family and cousins and that it was a happy home. Such is how parents shield their kids from harm.

Finally in late February 1933 Bruce got the call from Signal and both he and uncle Henry went back up to Elwood. They would both stay with Signal for the rest of their working lives.

Eileen had been in the hospital for a couple of days. She had intermittent contractions but nothing too serious until later in the day Tuesday the tenth of March. Bruce arrived at the maternity ward just after four o’clock. It was a fine day, one of those familiar California winters near the end of the rainy season. No fog in Santa Barbara, a riffling breeze drifting out of the desert to the east bringing a promise of warmer temperatures and springtime. A fortunate time to bring a new life into the world.

There was no sound. Six miles below the surface of the Pacific Ocean, rock stirred. Billions of tons of the earths crusts, caught along a crack, Jerked, lurched as they slid by one another at around a sixteenth of an inch a year. The immensity of caught forces gave way at 5:54 pm.

While her parents were at the hospital Barbara, Bob and Mariel and the Cayce cousins had just sat down to dinner, forks clinking against plates, the girls dicing up some boy at school, Bob rolling his eyes, trapped in a world of girls, when suddenly the table was gone, plates forks, knives and the stew Eileen had made just for the occasion splattered across the floor peppered with flakes of china. Too stunned to act they froze as the old wooden house began to shake and sway to a rhythm of its own. They were fortunate. Old wooden structures might skip and jump about in a quake but most survived with little damage.

At the hospital, as Eileen went into labor. Bruce paced the waiting room. In 1933 no man was allowed anywhere near the birthing room. He chained smoked Chesterfields and he waited. He’d heard nothing from upstairs and at 5:50 he decided enough was enough and he would go see what was going on. He was a few steps up the stairs when the Long Beach Quake of 1933 slammed into Santa Barbara. Bruce was staggered in mid-step, fell to his knees and tumbled back down the steps.

Eileen was in bed and had just delivered a baby girl. She was lying on her mothers belly as the doctor reached to cut the umbilical cord when the quake roared in. The bed skidded one way and the other with the nurses and the doctor desperately holding on, trying to keep the new mother and her child in it. The Long Beach quake** which was a terrible event shook Santa Barbara in a gentile way but that little girl who grew up to be my aunt Patsy was always ever after referred to by her father as an earth shaking event.

And that she was.

Coming: Chapter 19. The Depression

Cover Photo: Living outside, post earthquake, Santa Barbara California 1933.

*This is one of the events in our family history which has caused us to be pretty qualified government haters.

**In the early evening hours on March 10, 1933, the treacherous Newport-Inglewood fault ruptured, jolting the local citizenry just as the evening meals were being prepared. The Magnitude 6.4 earthquake caused extensive damage (approximately $50 million in 1933 dollars) throughout the City of Long Beach and surrounding communities. Damage was most significant to poorly designed and unreinforced brick structures. Sadly, the earthquake caused 120 fatalities.

Within a few seconds, 120 schools in and around the Long Beach area were damaged, of which 70 were destroyed. Experts concluded that if children and their teachers were in school at the time of the earthquake, casualties would have been in the thousands.

Michael Shannon is a writer, former teacher and a surfer. He write so his children will know where they came from.