Chapter 19

Michael Shannon.

Mans need to organize everything leads one to think that events you study are one off, a single illustration of consequential events. The events of the day, be they champagne cocktails at the round table in the Algonquin hotel, opening the package that came in the mail with the new Bennett Cerf book, fresh off the press, sitting at the radio and listening to the Amos and Andy the decades most popular show, or Tom Joad changing one worn out tire for another along the roadside between Oklahoma and California’s San Jaoquin valley. Life’s events for all for all of us are as diverse in experience as a flock of starlings twisting and turning in flight, each bird on it’s own yet part of the whole. History is like that.

Two weeks on the job with Signal Oil and he was down at the Ellwood pier using whipstocks to send the drill string out under the Santa Barbara channel like blind worms looking for food.

Soon after Bruce was promoted to assistant drill superintendant and he began to spend most of his time racing around California keeping an eye on production and solving problems at the wells.

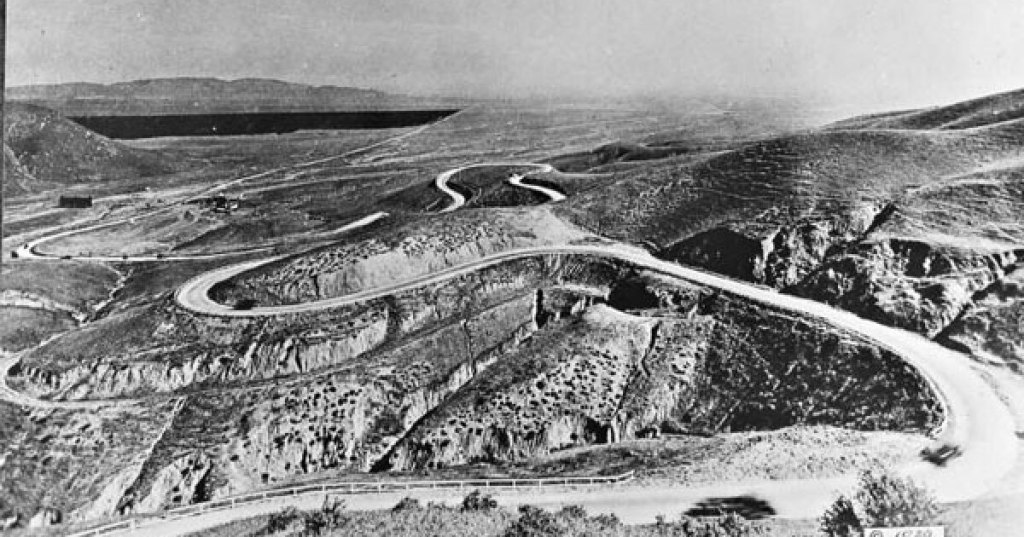

Most have forgotten in the days of eight lane freeways what that mean in the thirties to drive in southern California. Most of the roads we are familiar with either didn’t exist. Those that did were barely improved. Highway 99 was the main highway connecting southern and northern California. Entire section of it were still just crushed gravel, a few sections were asphalt and the section from Los Angeles over the Grapevine to Bakersfield had been paved with concrete in 1932. It was the finest road in the state except for the Grapevine part.

As with most roads the highway was originally a game trail. Wild game always seeks the easiest route and the first people to settle here simply followed those trails. the Spanish and Mexicans widened the trails for wagons and our original roads simply did the same. That didn’t make it easy. Many cars built in the twenties and before didn’t have things we take for granted today. Brakes were mechanical and had little serious braking power. Older models still used wooden spoked wheels and narrow tires. Radiators and cooling systems couldn’t keep up with serious heat. You will notice old photos of cars that have a water bag hanging on the radiator as an extra precaution. Steep hills were a big job for underpowered engines.

The Grapevine looking down towards the Elk hills in the left background. The dark area is Tule Lake which no longer exists but was once the largest lake in the west. The oil fields are at the foot of and up the sides of those hills. The Oildale rigs outside Bakersfield are on the Kern river 57 miles to the right.

Near the Elk Hills and the Temblor range are Avenal, Coalinga, Maricopa, McKittrick, Fellows, Reward and Ford City. The Halls lived in them all. The Maricopa/Sunset fields the third largest fields in the US are still in operation today nearly 150 years after the initial discovery of the famous Lakeview gusher.

Variously called the Grapevine or the Ridge Route as it passed out of the San Fernando valley was a nasty twisted and turning road. Grapevine precisely described it. Twisting and turning back on it self as it navigated the mountains that divided Los Angeles county and the southern end of the San Jaoquin valley it was a road to be very wary of. Bruce Hall was familiar with every inch of it. It was nothing for him to get a phone call in the middle of the night and upon answering be ordered to go trouble shoot a well in the Sunset. Gassing up near the house in Compton, Artesia, Wilmington or Long Beach, they lived in all of those too, he would grab the lunch and thermos that Eileen made for him and drive straight through. It was a four hour trip in those days of the depression. He’d meet with the crews, figure out how to fix or solve the problem then turn around and drive right straight back. Sometimes he would cross over to the coast through Cuyama and down the Cuyama river through the old ranchos on all dirt roads to see his parents in the Verde district of Arroyo Grande. He could check Signals wells in the Arroyo Grande field out Price Canyon way then head home by the Santa Maria/Orcutt fields where Sam Mosher held some leases. Going back by the coast took him by Ellwood where he could stop in Hope Ranch to see Eileens brother Henry and his sister-in-law Martha. Henry also worked for Signal. He was a mechanic so the Cayce’s stayed put for most of his career.

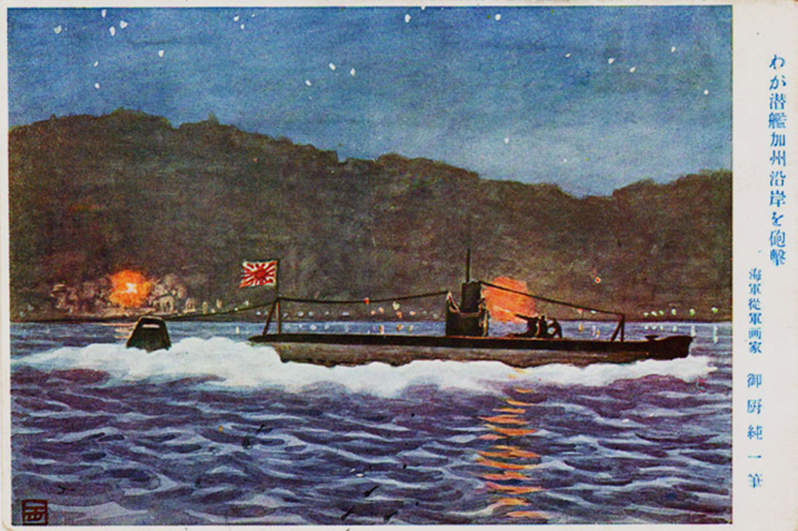

Uncle Henry was famously at work when at around 7:00 pm on February 23, 1942, the Japanese submarine I-17 came to a stop opposite the Ellwood field on the Gaviota Coast. Captain Nishino ordered the deck gun readied for action. Its crew took aim at a Richfield aviation fuel tank just beyond the beach and opened fire about 15 minutes later with the first rounds landing near a storage facility. The oil field’s workmen had mostly left for the day, but a skeleton crew on duty heard the rounds hit. They took it to be an internal explosion until one man spotted the I-17 off the coast. An oiler named G. Brown later told reporters that the enemy submarine looked so big to him he thought it must be a cruiser or a destroyer until he realized that only one gun was firing.

Firing in the dark from a submarine rolling in the waves, it was inevitable that the rounds would miss their target. The 5.5 inch Japanese shells destroyed a derrick and a pump house, while the Ellwood Pier and a catwalk suffered minor damage. In a kind of cosmic joke they also obliterated an outhouse which after the bombardment uncle Henry said he sorely needed. After 20 minutes, the gunners ceased fire and the submarine sailed away. The workers did the only sensible thing, they called the police.

A funny little story at the beginning of a savage war. Santa Barbarans raised money to dedicate a P-51 fighter plane to the war effort, They called it the “Ellwood Avenger.” The Avenger went to a training base in Florida and never left the states. For the Japanese, they issued a postcard to raise war fervor at home. It was all a little silly and made an oft told story in the Hall and Cayce families.

Though Bruce’s job was pretty secure, Signal Oil had to continue to scramble to produce enough crude to satisfy the demands of its contracts with Standard. Not a minute nor a drop of oil could be wasted. The crews could not make a mistake so constant vigilance was the order of the day. Bruce’s company car was seldom home for very long and typically spent most of the time parked at a well site.

When he and Eileen sat down at the table the most important part of the conversation was liklely to be their kids. The constant worry for their children was the same then as it is now. They were very aware that with Mariel and Barbara entering high school and Bob right behind the constant moving was getting hard to bear for the kids. Moving seven times in just four years there was bound to be trouble or at least a great strain on education especially for the girls. Santa Barbara, Taft, Compton, and Wilmington high schools varied widely in quality and the kids couldn’t help but feeling apprehensive about what was coming next.

What they decided to do was to make every effort to somehow stay in Santa Barbara until both girls graduated high school. It was a choice my mother applauded.

Chapter 20 is next.

Surviving the depression.

Cover Photo: Taken in Anaheim California in 1934. L – R, Dean Polhemus,* Donald Polhemus jr, Mariel Hall, 16, Evelyn Polhemus, Aunt Christine Polhemus, Eileen Hall and Barbara Hall, 14. The Polhemus kids were first cousins. The Halll’s were spending two weeks with the family, down from Santa Barbara.

*Dean Polhemus figures in the story NAQT which is about his service aboard the USS Spence in WWII. You can follow the link below.

Michael Shannon lives in Arroyo Grande California where he grew up. He writes so his children wiill know where they came from.