CHAPTER SIX

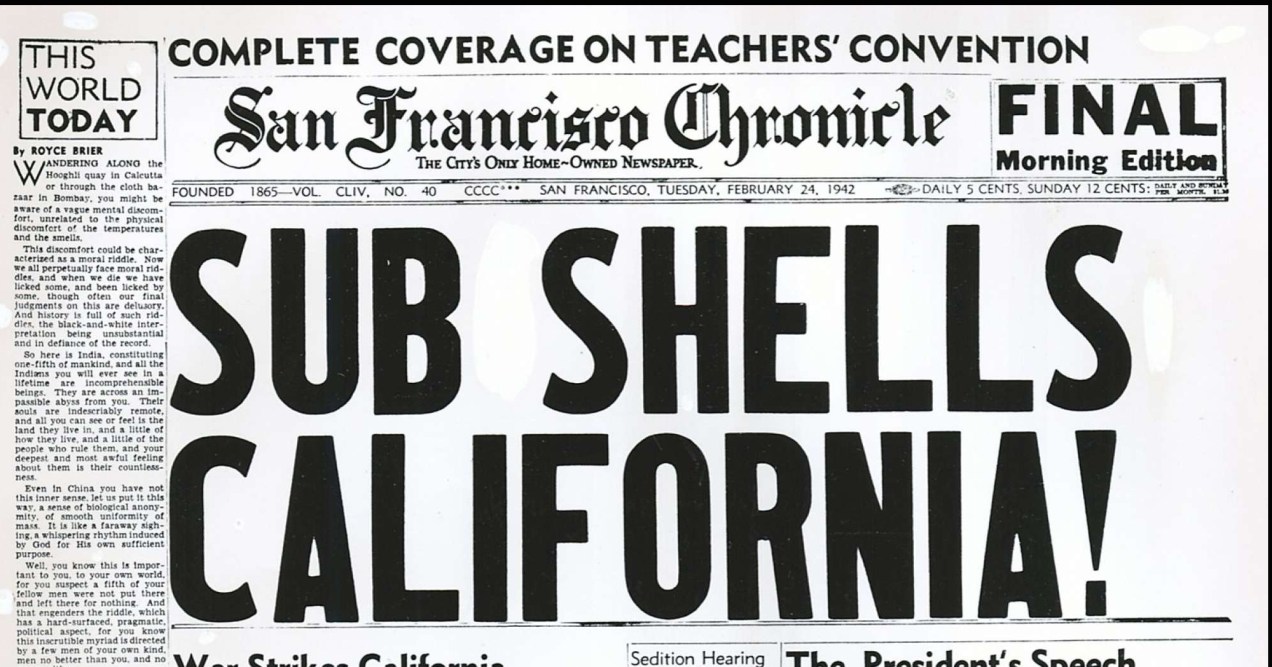

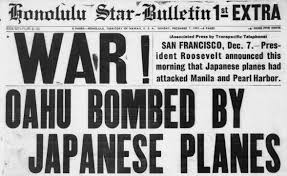

Headed southwest from Hawaii the crewman of the Spence began arranging storage for the supplies and gear they had brought aboard at Pearl. During the Naval build up in the Pacific the initial push was for warships at the expense of the ships which supplied logistics. Tankers, repair and supply ships were being added to the fleet as fast as they could be built, but in 1943 there weren’t sufficient numbers available yet. The war in Europe took precedence over the Pacific. Fighting in North Africa had just concluded in May and the buildup for the invasion of Sicily, which was to begin in July and then followed immediately by the invasion of Italy in September. Meanwhile planning for Normandy which was to be in June of 1944 went ahead. All these operations required an enormous quantity of shipping which wouldn’t be available to the Pacific fleet for some time yet.

Cutting corners, scrimping on supply were to be the watchwords on the Spence. Each department went about checking and rechecking what they had aboard. The greatest difficulties faced by the Navy in the Pacific and the least understood at home were the distances involved. You could drop nearly three Atlantic Oceans into the Pacific. Distances were vast. Shipping between continental Nova Scotia and Ireland was less than 2,000 miles. San Francisco to Honolulu alone was over 2,300 and if you continued eastward more than 10,000 miles to Shanghai, China. Escorting the convoy, Spence expected to travel for over three weeks to get to the Solomon Islands. Destroyers are amongst the fastest ships in the Navy but in a convoy they must travel with the slowest ships. There would be plenty of time to make sure everything was just right.

It was a terrific problem for logistics to keep the fleet supplied with the thousand and one things over and beyond food, fuel and ammunition. “Want of a nail,” Ben Franklin’s Old Saw is an absolute law for a fleet at sea. The Spence needed everything you find in your home, everything you need at the office and everything you need at work. She had watchmakers, Blacksmiths, boilermakers and laundrymen, and tailors, cooks and bakers. She carried machine-tool operators, draftsmen and dentists, men who could repair a typewriter and other men who could rebuild a steam turbine and metal-smiths and a master diver. She had gunners, torpedo men, yeoman, radiomen, signalmen and quartermasters. She carried a master machinist and firemen. All the seamen needed to operate the ship were also aboard. And each man carried the tools of his trade. The signalman needs needles and thread and a sewing machine to repair signal flags soon to be whipped to pieces by the wind. The machinist has to have every possible wrench, gasket, bolt, screw and spare parts for the main engines, pumps, fans and all the auxiliary machinery. There is no handy store just around the corner.

The boatswain mates, John Esler, Samuel “Sonny” Rosen and John Saxon ran a school for seamen. Sailors on the deck crew were divided into three watches and it was the responsibility of the Bosuns to school them up in order to maintain the ship. The new kids that had come aboard at Pearl were from all over the country and if one had any experience working a ship it would have been a surprise. A fisherman’s kid would have been “encouraged” to unlearn everything he knew about seamanship. There was the Navy way and none other.

There are no sit down classes on shipboard. It’s all learned on the fly and under pressure. A good bosun owns the ship and you had better figure that out right away. A 376 foot long machine at sea takes a great deal of punishment. Salt water corrosion, the constant working of the hull in a seaway mean that there is never enough time to do all the task necessary to keep everything in good order.

Chipping paint every day, decks, bulkheads, and every part of the superstructure that needs maintenance. If a man is a slacker, well he can crawl between the lowest deck and the ships frame and chip in the ‘tween spaces, laying on his back and scraping rust in the near darkness. Is he claustrophobic, no one cares, he has no choice. Perhaps he will change his tune after that. At Pearl Harbor and the first sea battles of the war they discovered that layers and layers of accumulated paint caused catastrophic fires so now ships were constantly stripped and repainted to reduce that possibility. All the porthole curtains, officers rugs and upholstered chairs were left at Pearl or thrown over the side. Absolutely everything that could burn and could be spared was gotten rid off. If your ship is burning you have nowhere to go but over the side. Every sailor in the Navy goes to firefighting school and practices constantly.

The kid from the midwest is likely to know what a rope is. The problem; there is no rope on a ship. There are lines, cables, hawsers. stays, breast lines, spring lines but no ropes and woe betide the swab that calls them that. You have to know the difference between a hitch and a bend or how to backsplice. Know where the bitter end is and how to find the Pelican Hook.

Better learn in a hurry too. Bosun’s are supposed to be tough. They don’t stand for any nonsense. John Saxon was one of eight children born to parents who had immigrated from Slovakia in 1913. His father was a laborer and spoke Slovak and just a smattering of english. His mother stayed at home and raised kids. His brother John was in the Navy and his younger brother worked in the Merchant Marine as an Able Seaman. At five eight, 170 pounds, when his grey eyes narrowed, you’d better set to with a will.

Those assigned to guns learned how to dismantle, clean, oil and reassemble their charges. Gunners Mate Frank Baeder came from central Pennsylvania, the descendants of German immigrants who arrived in America just before the revolution. As a Gunners Mate his primary purpose was to see that his men could fix any part of the guns they were assigned. They must be able to operate them at lightening speed. As they headed west the gunners practiced everyday, firing at sleds towed by other ships or sleeves towed by the catapult planes from cruisers and battleships.

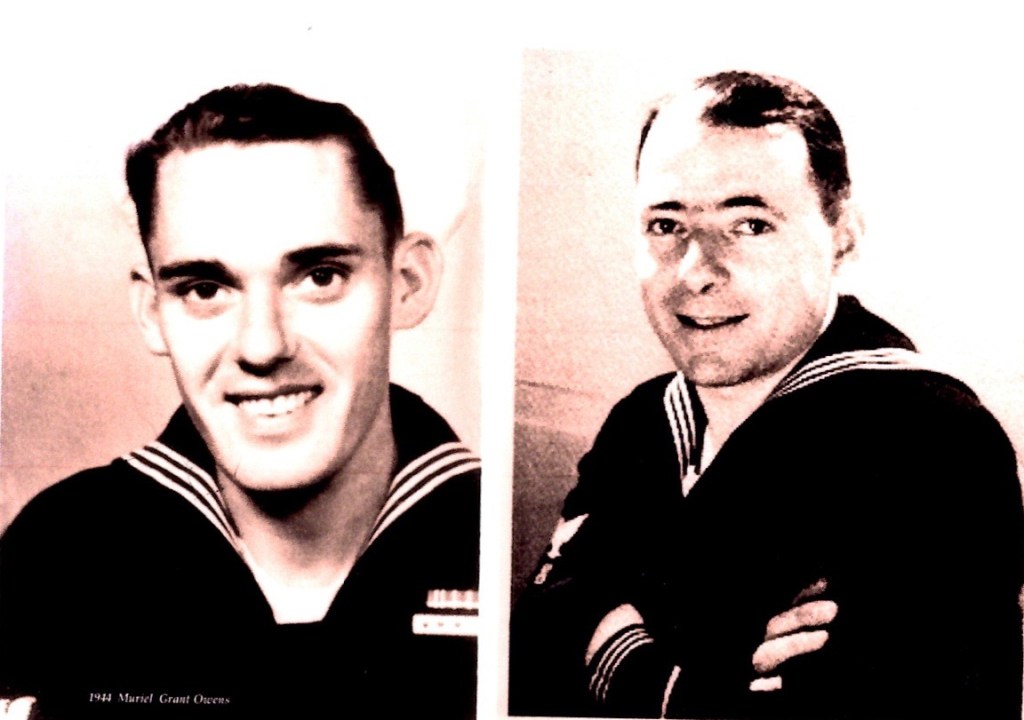

Muriel Owens, was born just a year before Don Polhemus. He came west from Lawrence, Missouri with his parents Arlye and Golden “Goldie” Owens during the dust bowl years. His parents were fruit pickers but managed to get all four of their kids through high school in Anaheim. His brother Royce had been lost when the Jacob Jones DD-130 was torpedoed off the coast of New Jersey in 1942. Only 12 sailors survived. Muriels brother-in-law, John Ladd was also aboard Spence. His little brother Holly was stationed on the USS Kaskaskia AO-27, a fleet oiler and would have occasion to fuel the Spence during combat operations in 1944. The Owens family displayed four stars in their front window, one Gold and three Blue.

Whether his mother taught him to sew or not, Muriel could make a sewing machine hum now. He was an expert at morse code, could read signal flags, send wig wag and operate the blinker lights with lightning speed. In enemy waters, radio communications were kept to an absolute minimum as the enemy was likely listening. Visual replaced TBS, “Talk Between Ships” with few exceptions.

With the loss of the Philippines, the Dutch East Indies and Singapore there was now not a single large scale naval base between Pearl Harbor and Colombo, Sri Lanka or Bombay, India. This created a task of gigantic magnitude for the Service Force of the Pacific Fleet. The Service Force had to supply the needles, thread, bolts, typewriters and paper for the fighting units. All the imponderable paraphernalia of sea warfare was carried across the vast Pacific by navy and merchant freighters, tankers and repair ships.

As she cut westward through the waters of the Pacific, each turn of her screws shortened the time before she would have to nestle up to the big ships and take on fuel. Replenishments or Reps are a friendly affair. Talk between ships in good weather can be done without a megaphone and on deck crew can talk to their counterparts aboard the bigger vessel. The bigger ships sends over little luxuries like fresh bread, ice cream, magazines, books and soft drinks as the smaller destroyer bounces and tosses alongside. Occasionally the ship’s band would serenade the Small Boys churning nearby.

Captain Henry Jacques Armstrong, Naval Academy 1927 was from Salt Lake City. He had served in a variety of ships in the years before taking command of the Spence in 1942. An experienced ship handler he loved his little ship and liked to handle her like a hot rod. When approaching a carrier or tanker to fuel, he would run up to the larger ship at 30 knots, nearly top speed and then “Crash Back” by reversing the screws, the same as slamming on the brakes, slowing the ship to the same speed as the larger ship at the last moment. His crew loved it. The dashing little ships gave fits to the the larger ship’s captains, sometimes causing a little consternation on their bridges. Captain shouting through the megaphones to “Get that damn ship away from the side.” Perhaps a little jealousy too, from the officers on the plodding giants.

Three hundred twenty nine men on the Spence may seem excessive but the needs of a wartime ship are legion. Like any other organization destroyers are divided into departments. Each department is responsible for certain duties applied to the running of the ship. Most visible, of course, is the first division which is responsible for the upkeep and operation of all things topside. Chipping and painting, tying up and letting go when entering or living an anchorage, fueling both at anchor and while underway and the general physical plant above deck. Deck division sailors are also used by the other ships departments as needed. First Division provided the majority of the bridge watch standers and the gun crews. The Gunnery Officer – Or “Gun Boss” was responsible for operation and maintenance of all of the ship’s armament plus all matters relating to deck seamanship.

The Boatswain’s Mates (BM) was generally considered to be the senior enlisted rating in the navy, a tradition probably handed down from the days of sail. The Chief Boatswain’s Mate (BMC) was expected to be the most capable seaman on board. Often he was assigned additional duties as Chief Master at Arms (The ship’s head policeman). The other rated BMs were generally assigned individual sections of the ship to maintain. This was a very prestigious assignment and these Petty Officers generally lorded it over the junior non-rated sailors in the division. Sometimes lovingly referred to as “Boats,” the Chief Bosun was a real sailor man. Boats was also involved, under the purview of the Chief Executive Officer, Frank Van Dyke Andrews out of Coronado, California, in the planning, scheduling and assigning of work to the deck crew on ship. In wartime the Navy takes almost anybody who can stand up and the deck crew would have had it’s share of undereducated scoundrels. Though there is a formal process for issuing discipline the Boatswain’s mates had to be handy with their fists. Minor infractions could and were handled with a rough sort of discipline that would have been recognized in Admiral Nelson’s Navy. Regardless, the deck crew was proud of their standing in the navy and took great pride in it. Referred to as “Deck Apes” by other sailors they took a perverse pride in their toughness and the name. Boatswain Mates were superb at “Make Do,” they could find it, fix it or make it when they had to.

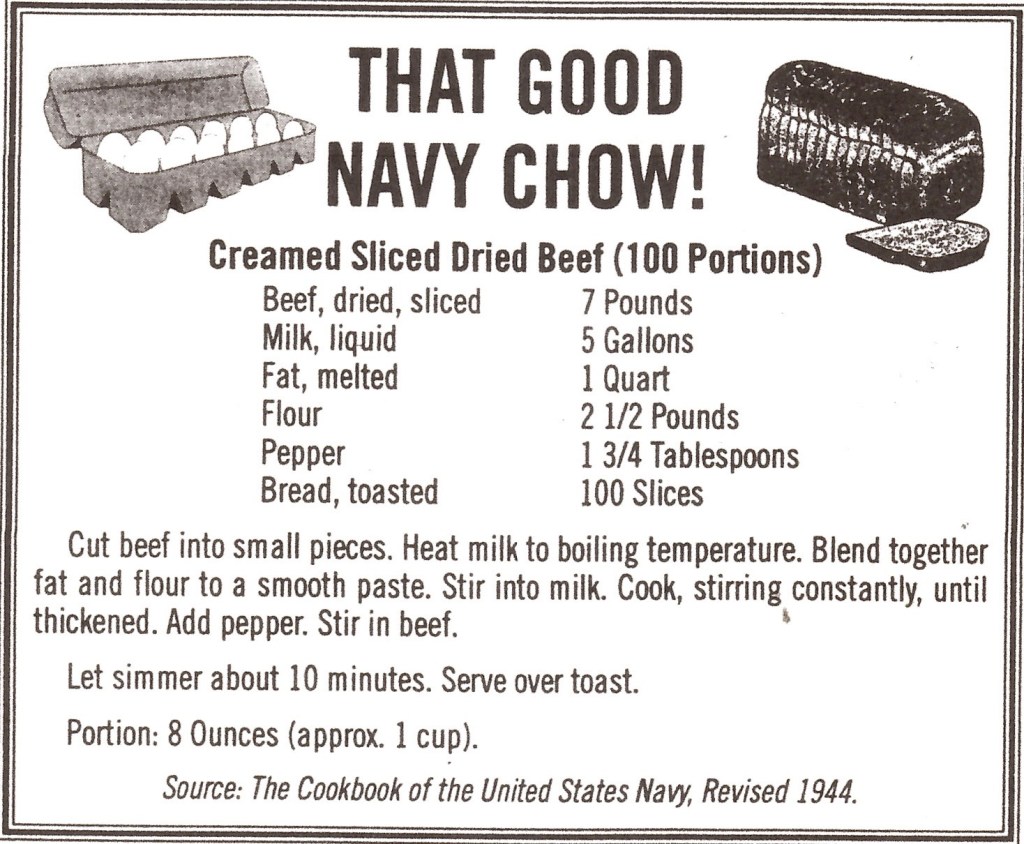

Don Polhemus’s department was Supply. His officer was Lieutenant (JG) Alphonso S “Al” Krauchunas, twenty four, from Kalamazoo, Michigan. He was born in a Wisconsin farmhouse to Lithuanian immigrant parents and like most of Spence’s crew never saw the ocean before coming aboard in April 1944. A supply and disbursement officer, he was in charge of “S Division” which was the pride and joy of her crew because of the excellent meals provided them daily by a dedicated group of cooks and bakers. Lest you imagine a gleaming commodious galley, think again. So small and cramped that the cooks literally climbed over each other and hotter than the shades of Hades, working 24 hour a day in three watches, they provided meals for 329 men three times a day plus plate of sandwiches for watchstanders in the long hours of the night. Each meal took in excess of 2 hours to serve with sailors standing in long lines outside the galley. Hot blistering sun, boondockers burning the soles of your feet and Dixie Cup turned inside out to protect the ears it better be chow worth waiting for. Not every ship was as lucky as Spence. It took a supply department who worked hard, used a great deal of ingenuity in procuring food supplies and perhaps some sly Cumshaw on the side.

The Lieutenant was also the paymaster. These duties made him a popular man with the crew and he was known as Lieutenant “Pay” when he was out of earshot. All hands learned that the husky young officer at five foot ten and 200 pounds was a stalwart shipmate, ever ready to lend a hand when needed.

Alfonso Krauchunas was a graduate of Western Michigan College where he starred as a hard hitting, slick fielding shortstop. He was signed by the Chicago White Sox and was playing in the minors when the war broke out. He enlisted in the Navy as an enlisted man before being commissioned as an ensign in the supply corps. He was a physical education major in college and was a strong swimmer. This skill was important for he dove overboard twice in the Marianas campaign and swam 80 to 100 years to save downed pilots who were floundering and about to drown. The second time, riflemen commanded by Chief Bosun John Esler fired on and fought off several sharks headed for the swimmers.

The officers had a tiny pantry adjoining the wardroom and a section of the main galley is assigned for their use. The cooking, serving and quarters cleaning is done by the stewards department who have no other duties except at general quarters where every man in the crew has a battle station. The mess men on the Spence were all black. The Filipino stewards of earlier days were no longer enlisted in the Navy in 1943 and the other traditional stewards, the Chamorro’s of Guam were unable to serve because Guam was now held by the Japanese. Their battle stations on the Spence were in the lower handling rooms and magazines. They worked at sending powder and shell up the hoists to the 5inch/38 gun turrets. They passed the ammunition just as efficiently as they did the potatoes in the wardroom.

Rosevelt Copeland was one of those stewards. Rosevelt was from Mansfield, Louisiana. His mother Fannie had to sign for him in order to join the service, being too young to volunteer on his own. He had just turned sixteen so they lied about his age. Rosevelt was from one of the poorest parishes in Louisiana, De Soto. Rosevelt’s father had been as a cook in WWI and had served in France. While Rosevelt was a little kid he cooked for the local hospital. The hospital was a converted plantation house of two story and an imposing building when Rosevelt was growing up. In the tiny town with unpaved streets, he lived Jim Crow south every day. Sugar Cane was the business and antebellum south was visible all around. There were homes still standing from pre civil war days such as the famous Shadows on the Teche, a plantation dating to 1834. Wakefield, Belle Grove and the Lady of the Lake plantations still dominated working life . Each one a constant reminder of his place. By 1940 his father Edgar was gone to Bossier City, no longer around. It’s hard to imagine what his mother thought about signing those papers. His older brother was married when the war started and had only completed the third grade and of his two sisters, Maggie was nearly illiterate and Mattie had died before her first birthday. With a population over 80% black the Navy must have to seem to the young man a sort of salvation. Perhaps the only way out. At seventeen he was the youngest member of the crew.

Fred Cooper was the ranking Steward, wearing a 3rd class crow.*. He had signed up in Shreveport Louisiana in November of 1942 with Rosevelt Copeland and both had come aboard Spence when she was commissioned. Fred had lived with his widowed mother Gurtha in a section called Calumet heights south of downtown. Known as South Chicago, the area had been the destination for Blacks migrating from the mid-south all during the depression,. They were fleeing the grinding poverty and lack of any opportunity to live a better life. Fred’s mother brought him up from Arkansas in 1932 and by 1940 was living in a rented house, taking in lodgers to help make ends meet. Her principle lodger in those days was Judge Wilkinson, a railroad porter. He worked the Chicago and Northwestern RR. A Porter was considered to be one of the best jobs a Black man could have. In 1940 he worked all 52 weeks and earned a yearly salary of 1,000 dollars which was comparable to a skilled white tradesman. Gurtha earned 300 dollars working as a presser in the retail trade which meant that Fred would have had a fairly comfortable life. Fred had a high school education which was becoming common in the late forties for Black kids. The lodger, Judge was born in Mississippi to a sharecropper family, Andrew Jackson Wilkinson and his wife Alice. Judge had come north in 1932 to work on the Railroads. He and Gurtha both listed themselves as single but were likely living as common law married as she gave her name as Wilkinson on the 1940 census form.

The officers pay for their own food which they buy on shore or from the ship’s general mess. To plan the menus, collect mess bills and keep accounts an officer is elected as the Mess Caterer. He is usually very junior and often a lowly ensign serving his first tour. He sits at the lower end of the mess table at the opposite end from the President of the Mess, the Captain. His term of office is entirely dependent on his own ability and interest. His only job is to see to the state of abdominal contentment of his messmates. Some mess caterers stay in the job for long periods, others are voted out at the end of the month, if the mess bills have taken a sudden and unexplainable rise, if the quality of the food has drooped out of sight , or if the unfortunate caterer has sought to swing the mess toward his own particularly affectations. If a junior officer complains constantly about the food being served he is sure to be voted in next month on the “Lets see what you can do” basis. There was a story going about the Navy about an island boy from Guam whose command of the language was at best imperfect. The first time he was examined for promotion he was asked the first question which is to define the difference between a command and an order. The Navy Training Manual explains it as, in effect, that an order allows for some initiative in how the order is carried out; a command is arbitrary and inclusive. The steward from Guam had his own ideas. “An order,” he said, “is ham and eggs. A command is bring ’em in.” He got his promotion.

On a destroyer the bakeshop is a four by four space. The Bakers can turn out light crusty bread, delicious pies and cake. Unfortunately a design flaw led the baking ovens exhaust up near the bridge. On baking nights, the mid- watch, from midnight to 4 am was as hazardous as the Japanese were to the watch standers on the bridge who had to smell the odors wafting from the ovens exhaust. Many a seaman was laid low by the aroma of baking apple pie. For this savage duty, they were usually allowed into the galley first for breakfast and, just perhaps received a slice of pie with chow. Every ship in the Navy held mid-watch snacks as sacred.

Baker first class Charley Craver cut his teeth working at the Romeo and Juliet Bakery in Miami before going into the navy. The Spence was lucky to have a man of his talents. He was backed up by Bkr 2nd Shelby Ryals from Lowndes, Alabama and Johnny Kaufman, Bkr 3rd. Shelby Ryals had worked for the American Bakery Company in Montgomery, Alabama and likely knew what his rate would be the day he put his employer’s name down on his enlistment papers. Sailors and officers stepped lightly around these men, they knew which side their bread was buttered on.

Two of the ranking petty officers in Krauchuna’s department were Don “Poley” Polhemus and Charley Reed Bean from Moorefield, Hardy County, West Virginia. Charley had a fit name, Bean, for he was one, 6′ 2″ and only 160 pounds he was a string bean. He had the blue eyes and ruddy complexion of his forebears. Moorefield was very small town folded into the corduroy mountains of the Appalachian Plateau west of the Alleghenies. They were almost due west of Washington DC. Only about 100 miles west, Hardy county was not just a world away when he was born but almost a galaxy distant. Situated on the south fork of the Potomac, Moorefield was just a speck, a far, far distant place. Charley was born from pioneer stock who had lived in the same small county for over two hundred years. His parents, Orvan and Essie where good solid Irish stock, the kind of people who persevered. They had little schooling and ran a small bee keeping operation while he worked in the lumber mill. He originally hailed from Snyder Knob and she from Capon Springs, both in Hardy county. Charley, born in 1923, the middle child of three. With the advent of family radios he must have dreamed of a world outside the mountains he was raised in. His was the first generation raised on radio which brought in the world outside the small world of Moorefield. He finished high school school in 1941 and went to Hagerstown, Maryland to work in the Fairchild Aircraft factory. Fairchild was feverishly building PT-19 trainers for the Navy and Army Air Corps. It was a good job. Training as a machinist, the same as “Poley,” both would have received essential industry deferments but neither wanted to miss out. Charley joined on up, the Navy was for him. Perhaps to see the world or maybe as a way to avoid ground combat or falling out of the sky. Who’s to know, they just did what young men have always done, they got in the fight. War is a very young mans game.

The engineering department was just what it sounds like. The Chief Engineer bears responsibility for operation of the ship’s engineering plant, electrical generation and distribution, auxiliary machinery, and interior communications. A warship is festooned with pipes, cables, ducts and many other systems that allow for the operation of all of it’s systems, any of which could cripple a ship in combat or sea conditions if allowed to fail. If there was ever any doubt about who was responsible for a piece of equipment on the ship, it belonged to the Chief Engineer. He was also responsible for coordination of shipyard overhauls or periods (availabilities) alongside a tender. The operation of the Two separate engine rooms were his direct responsibility. Why two? A Destroyers main defense isn’t necessarily it guns, it’s speed. It takes superb gunnery to hit a ship several miles away when its able to travel 44 miles per hour. Serious damage to a ships engine room, either fore or aft allows the vessel to continue maneuvering. Loss of both engine rooms and the ship becomes a sitting duck. The engine rooms are the spaces where the Snipes work. Engineers were always referred to as “Snipes.” This term originated in the British Navy when a visiting Admiral said that the engine room on a battleship resembled a “snipe marsh”. Jobs in the engine room many. There are throttle men who take the engine room telegraph signals from the bridge and open and close steam valves to slow or speed up the turns the screws make, there are Wipers who do exactly what the name implies, Firemen the jacks of all trades, Boiler Tenders who see to water levels in the boilers, and Machinist Mates who maintain all the machinery in the engine spaces and above decks. If you picture a clean and healthy environment this is not it. It’s extremely noisy and a thin film of oil floats in the air, especially hard on the engine room crew because bathing is only a remote possibility. Above all, it is hellishly hot. In the tropics temperatures routinely exceed 130 degrees even at night.

One of the most important men in the engineering department, usually a First Class BT (Boiler Tender) and was designated as the “Oil King”. He was responsible for all fuel transfer operations plus chemical testing and treatment of the ship’s boiler water. Normally he was a non-watch stander and he was usually provided with at least one full time assistant. All records of boiler water treatment and fuel usage were kept in an office referred to as the “Oil Shack”. The BT rating was considered to have the hottest and dirtiest jobs in the navy. Contrary to what you might think, fuel oil and water are held in numerous tanks throughout a ship and particularly in small narrow ships the contents of thee tanks and the amount they contain have a great deal of importance in keeping the ship in trim. According to the condition of the sea, calm or stormy, the speed at which the ship is traveling and whether or not it is running before a swell, breasting one or sailing parallel to the waves the “Oil King” is primarily responsible for arranging the contents of these tanks in order to maintain stability. The Spence would have held roughly 61 tons of fuel fully loaded or about 188,000 gallons. Steaming up through the slot at 25+ knots she burned about 55,000 gallons every twenty four hours. The “Oil King” needed to balance his load constantly as fuel was burned and be aware that he needed to refuel every 3 or four days depending on conditions. BT-1C Frank Horkey was from Pasadena, Maryland, one of the three children of John and Ada. John Horkey was the son of immigrants from Bohemia and had worked as a stevedore and a carpenter in the shipyards at Maryland Shipbuilding and Drydocks. Young Frank had to quit school after the sixth grade and ended up working at the massive Sparrows Point Bethlehem Steel plant in nearby Dundalk. His brother William worked for the Frank Shenuit Rubber company. Frank was from a solid working class family typical of those that sent their boys to the fleet.

The Oil King had to be very careful in his work. A ship 367 feet long and only 39 wide and top heavy with guns and the superstructure is a very tender ship. She feels every change in wind direction and sea state. A Fletcher in a high speed turn will actually roll her fantail under water and that is in a calm sea. Forty degree rolls are common in almost any sea condition and in heavy weather a top heavy destroyer with insufficient ballast in its fuel oil tanks or seawater pumped into those empty tanks can suffer 70+ degree rolls and even capsize. The constant shifting and ballasting of the ship is an absolute neccesity.

In the tropics where the Pacific Navy fought, daytime temperatures average 80 plus degrees in the summer and cool off to 80 plus degrees in winter. Squalls and rain are an almost daily occurrence, and clear days average only about 6 per month. Rainfall in some areas is as high as 138 inches per year. The few islands with mountains such as Guadalcanal and Kolobangara in the Solomons to which the Spence was bound are relatively dry, averaging around 80 inches. The ocean temperature stays in the low 80’s and 90’s year round. Now apply these conditions to a steel ship in the days before air conditioning where the only cooling devices were the blowers that attempted to push air around the ship. With few openings topside and full height bulkheads dividing the hull into sections not only was cooling almost nonexistent but just moving around inside the ship was a chore. The only relief was after sunset when the air cooled slightly. If the ship was moving at speed the breeze helped, particularly if there was enough surface chop or a large enough swell that spray came over the bow and wet the deck. Sailors slept on deck whenever they could and it was common to step around sleeping swabs, fully clothed and using life jackets for pillows. These conditions were the norm when underway or anchored. Just doing your job was difficult under these conditions but the war in combat conditions put many extra and severe demands on crewman.

NAQT CHAPTER SEVEN

Steaming down towards the southwest, caracoling around the transports and carriers the Spence crossed the line for the first time. In the time honored tradition of seamen everywhere, King Neptune Rex ruler of the Raging Main swung himself over the side bringing with him his Royal Court to initiate all the “Pollywogs” aboard into the mystery’s of the Noble Order of the “Shellback.”

To Be Continued May 27th

* Crow is the naval term for the Eagle pictured on the rank badge that is worn on the upper sleeve of a petty officer. They appear on the badges of third class petty officers all the way up to Chief Petty officer. For example, Boatswain’s Mates, Gunner’s Mates, Torpedoman’s Mates, Signalmen, Quartermasters and the like were ‘right-arm’ rates, and their rating badges were worn on that arm. Conversely, Radiomen, Yeomen (office personnel), Ship’s Cooks, engine-room personnel . . . and that sort, were ‘left-arm’ rates, and the crows were worn on the left arm. This is no longer the practice. In 1948 all badges of rank were moved to the left shoulder. Deep water sailors hated that. In recent years the specialty insignia has been done away with, so a person can no longer tell which rating a sailor might be. The Navy is about tradition and sailors hate this kind of thing. Ratings are proud of their jobs but decisions come down from the Secretary of the Navy who is a civilian appointee and doesn’t give a damn what the sailors think.

Front-piece: DESRON 23 steaming in WestPac, 1944.

Michael Shannon is a World Citizen, Surfer, Sailor, Teacher, Builder and Story Teller. He lives in Arroyo Grande, California, USA. He writes for his children.