Category Archives: Uncategorized

The Taxman

Michael Shannon

The word ‘tariff’ owes its origin to the bustling Venetian trade with the Arab world during the 10th-15th centuries. The Arabic ‘arrafa’ meaning ‘notify’ led to the Italian ‘tariffa’ and through French it entered the English language.

Tariffs are fees U.S.-based companies pay the federal government when they import affected products into the United States. Since the money is collected by the government, it is considered a tax.

Still not clear? Lets take Willie Wonka for example. His factory needs Cocoa Beans to make chocolate. Cocoa refers to the seeds of the Theobroma cacao tree, which are the key ingredient in chocolate and chocolate products. The beans can be processed into various forms like cocoa powder, and butter. Commercial beans are grown in Central America, western South America, west Africa, India and Indonesia. None are produced in the USA.

So, Willie needs his beans. He will look to buy at the most advantageous rate he can find. Once the price is settled on he must pay the tariff on top of that. Lets say he pays $100 dollars a ton. To that he tacks on the tariff which we will suppose is 25%. The actual cost is now $125.00 dollars a ton. The tariff money is then remitted to the Federal Government. Willie pays the 25% then adds to his debit the cost of labor and incidentals to pay the tax, his accountants, bookkeepers, Fax machines and paper and all other incidentals included.

At the chocolate factory the arriving beans are processed, packaged and delivered to the retail outlets which actually sell to the consumer. This person is the “End user.”

If we assume that Willies net profit is say 10% on his candy bars he would lose 15% per bar. He will be bankrupt, no business can run such a large deficit and last very long. What can he do? Well, what he can do is simply raise the retail cost of his candy bar to cover the tariff which he has already paid to the taxman.

All things being equal, he is likely to raise his price more than 25% to cover ancillary costs above the tariff. (Tax) For purposes of clarity this means a $.50 candy bar will now cost as much as $.75 to 80 cents a bar to the end user. You.

Well what about the producer from Mexico you might say? There is no tax on him. His problem would be perhaps the reduction in the volume he is able to sell across the border of the US. But Americans like candy bars and Cocoa Butter so perhaps he will be OK. The idea here is to force the Mexican Cocoa Vato to lower his price.

So who is hurt? Not the treasury, they collect more tax money. It’s Willie, you and the foreign supplier. With across the board tariffs (Tax) which have been raised far higher, it means everything we import, the end user pays more, the tax. Do his wages go up to compensate? What do you think? You’re correct, he is poorer because the cost of goods he needs is higher. That new Ford 150? Forget that. The end user has less discretionary money to spend on a new vanity truck. The old one will have to serve. Ford is already importing parts from Canada, Japan, Europe and Mexico so there is a tax on each one which is added to the cost of the new truck. Slowing sales will push Ford stock down. Ford sales staff gets laid off. Mechanics get laid off, less gasoline is sold, fewer tires, probably a tariff on them too. See how it works?

Have tariffs (Tax) been around for a long time? Well over one thousand years. One of the tools used to attempt to balance trade, or the exchange of goods between countries they are a valuable tool when negotiated between the countries affected. Arbitrary imposition of tariffs (Tax) cause major disruptions in supply and the movement of goods and treasure around the world.

Imagine world trade as a vast spider web connecting countries all over the Earth. Even countries at war, another form of economics, will continue to trade. If you need an example of that, Standard Oil sold fuel oil to German submarines right up to Hitlers declaration of war on December 12, 1941. Casualties and destruction in Europe and Asia were not a consideration. Sales are sales. Henry Ford continued to build trucks for Hitler even after we went to war with Germany. He had the gall to sue the US government for the damage we did to his French and German factories by bombing them flat.

So, look around your house. See how many things you can find that are not made in the USA. TV, no, Those hip Chuck Taylor Converse tennies your kids wear? Sorry not made here. Your diamond ring? South Africa. The laptop you are reading this on, If it’s Apple is made in several countries, India, Vietnam and China. Add the medicinnes in your medicine cabinet, your furniture. Ikea anyone. Chemicals, precious gems, Aluminum, steel, magnesium, copper are what an airliner is made off, expect airfares to go up. Nothing will go untouched. Even companies who don’t import goods of any kind will raise their prices because thats good business.

Think about this. Even companies that manufacture nothing will raise their rates. If you buy a fancy schmancy BMW which is now going to cost 25% more than yesterday you can bet the your insurance company is going to raise your rates for a now higher priced car.

My favorite? Susan Collins, Senator from Maine stated that Maine blueberries are shipped across the border to Prince Edward island in Canada to be processed and when they come back their will be a tariff added to the sale price. That blueberry muffin at Starbucks? The beans in the coffee, the half and half, Canada. Forget it. No one is going to be untouched.

Economic policy is difficult to predict. It’s important to try but still its a cipher. There are many, many moving parts but there are some things I think you can be assured of. All these new tariffs, not negotiated but simply imposed by fiat are going to be a major problem for Willie and you. As always, economics are tied to your wallet. Buy one with a a zipper, your’re going to need it.

For a complete breakdown on the effects of predatory tariffs do some research into the Smoot-Hawley tariffs enacted in 1928/1929. That bill did not start the Great Depression but it contributed mightily to it.

Both JP Morgan bank and Henry Ford himself said they begged President Hoover no to sign the bill, Ford saying he nearly got down on his knees in the Oval Office. Hoover said that he must support the party and signed anyway. The US economy went right over a cliff. Ask your great-grandparents what that was like. How did we get out? Ask Adolph Hitler what that cost the world.

Michael Shannon is a former teacher of Economics and wrote one of the economic curriculums for high school used in California. He was also in the construction business for 27 years and knows that wood comes from Canada.

442nd RCT Erased.

Michael Shannon.

Members of the 442nd and 100th Infantry hold a captured Nazi flag in France, 1944. US Army photo

Something that should make you want to vomit. The United States Army has removed the page honoring the 442nd Regimental Combat Team from its webpage. If you don’t know who they were, they were the all Neisi Japanese Americans who fought in WWII. They were the most decorated small unit in the history of the Army. They, along with 100th infantry, a combat unit from the west coast, were American born boys who fought for their country even though their families were locked away in concentration camps at home. The excuse for removal? Trump and Hegseth’s insane attempt to stamp out diversity in the worlds most diverse country. By all definition they are evil.

My very good friends father, Isaac Akinaka was an army medic who fought in Italy and France. Local farmer Haruo Hiyashi was 442nd, the late Senator Daniel Inouye, whom I knew, lost his hand with the 442 in France.

These governmental fools are beneath contempt and should be treated so. If you are interested, attached a the link to the 442nd’s website. You can’t get it from the Army of the United States.

That’s So Gay.

Michael Shannon.

*That’s so gay,” in recent years has been used as an insult to mean “stupid”, “boring”, or “lame”.

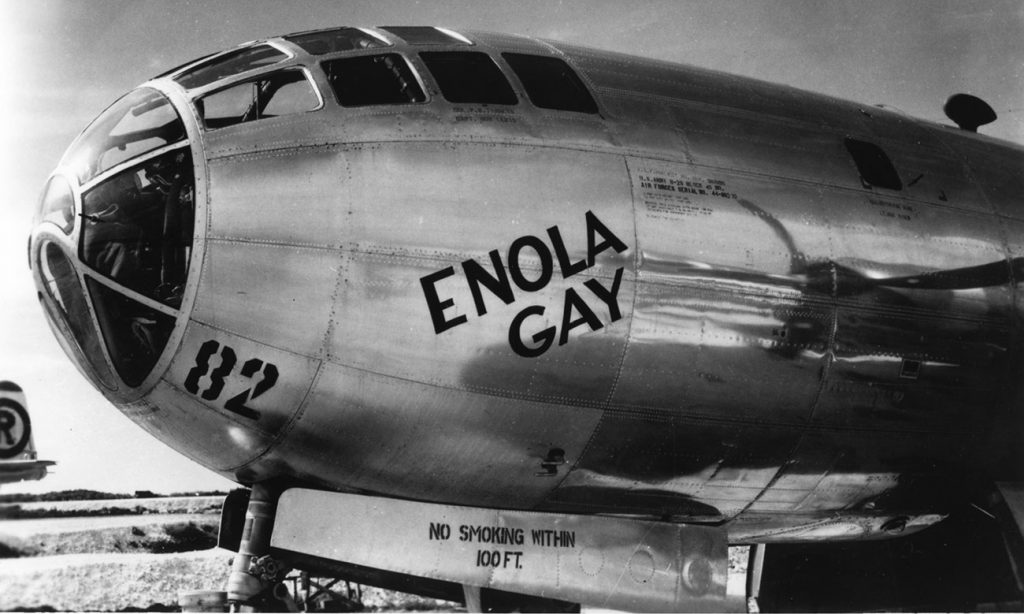

Mrs Tibbets. Her name is on the nose of one of the most famous aircraft in the world. She was the mother of the pilot, the man who sat in the left hand seat. She was an Iowa girl.

She and her husband Paul had two children, a boy and a girl. Paul jr. and Anne. In WWII, Paul flew B-17’s in Europe and Africa and was for a time the personal pilot for General Eisenhower. He worked on the development of the B-29 and as an advisor to the Manhattan Project. Sent to the Pacific theater in 1945, his B-29, named for his mother who had just passed away in July carried the worlds first operational Atomic bomb called “Little Boy.” It went to Hiroshima, Japan.

After the 2nd bomb nicknamed “Fat Boy” was dropped by a plane named “BocksCar” the Japanese surrendered.

The B-29 aircraft was saved from demolition in the 1950’s and is displayed in the Smithsonian Museum’s Air and Space Museum in Fairfax, Virginia.

Whatever you feel about the Atomic bombs, the plane is an important part of the history of the United States and Japan.

Coronal Paul Tibbets and the crew of the Enola Gay in August 1945. UPI photo

This month, the Secretary of Defense former national Guard reserve major Paul Hegseth, who served as a Civil Affairs officer overseas in the middle east. As an officer on the national guards career track he was given the Bronze Star which is what officers get just for breathing.*

Secretary Hegseth, a true MAGA believer is intent on removing portions of the military which he finds distasteful. Mention of Tuskegee airmen, gone, their photos too. Their crime? Being black. The Womens Air Service Pilots, gone. Their crime? Being women and women of color. Women of color who faced a double burden of racism and sexism in joining the WASP. A few were accepted, but their numbers were small. Pilots Hazel Ying Lee and Maggie Gee, who were of Chinese descent; Verneda Rodriguez and Frances Dias, who were Latina; and Ola Mildred Rexroat, who was Oglala Sioux, all joined the WASP. Mildred Hemmons Carter whose husband flew P-51’s for the Tuskegee airman was rejected because she was Black even though she was already a highly experienced pilot. Even a United State Marine who won the Congressional Medal of Honor in the Pacific was erased. His crime? He was Portuguese-American. He gave his life on Okinawa. Harold Gonsalves was his name. Wrong color I guess.

The Enola Gay has been canceled too. A big silver plane, a machine, no brain, no heart, just a machine. Thinking individuals will be unsurprised to learn that the Enola Gay was not actually named after the sexual orientation. The plane was named after the mother of its pilot, Col. Paul Tibbets, Enola Gay Tibbets. The plane was not gay. Everyone knows that all planes are female just like ships. Thousands of photos and image descriptions including someone with the last name “Gay” have been flagged for deletion. The same thing has happened with a photo of members of the Army Corps of Engineers, his last name was Gay. There are still tens of thousands of photos, textbooks and other notices to go through before they are finished.

They’ll get Doris Miller too. Not only for the fact that he was black but had a womans name to boot. Doris’s heroic actions stirred the nation in 1941, but he was not formally identified or recognized for his role in saving lives at Pearl Harbor. No need to guess why.

Hegseth ordered the Pentagon to scrub any and all digital content that promotes diversity, including months that celebrate cultural awareness, from department and military branch websites and social media. No MLK day, no black history month and especially no Pride Week. The directive stated that all “information that promotes programs, concepts, or materials about critical race theory, gender ideology, and preferential treatment or quotas based upon sex, race or ethnicity, or other DEI-related matters with respect to promotion and selection reform, advisory boards, councils, and working groups” should be removed, with limited exceptions for content required by law.

Apparently Medals of Honor winners, women who gave their lives in service to their country or airplanes are protected by law.

PFC Harold Gonsalves, who received the Medal of Honor for his heroic actions during the Battle of Okinawa in 1945. A Portuguese American boy from Alameda, California. 4th Battalion,15th Marine Regiment.

Sounds like double speak which the military and Hegseth do well. Hegseth was a Fox host after all.

WTF, to coin a phrase. The United States is the most culturally diverse country on earth. That is our super-power. What is the matter with those people?

*A career officer must be able to wear proof of his service on his breast, hence superfluous awards. Likely it was awarded for a paper cut since the secretary was a publicist and journalist. Enlisted men must be shot or killed to get a Bronze star. Big difference.

Michael Shannon is a writer from California. He is a Vietnam veteran and has an eye for stupidity. which he tries to avoid like the plague.

This Country

Michael Shannon

I’e been thinking lately about who we are in this lovely country. We are kind. We think of others. We are free with our earnings in order to help the unfortunate. We ask for nothing in return.

We are marvelous creators. There are the engineers who have built this country with their inventions. There are the painters and printmakers who capture the spirit and the sublime looks we are fortunate to have. Our National Parks are the glory of this country, something no other can match. We have embraced immigrants from everywhere on earth. They have made us better.

One of the reasons that the American language is so diverse and adaptable is the fact that there are at least four hundred and thirty separate languages spoken in this country, which contributes to our distinct spoken word.

Our greatest single export is is our music. We’ve taken seeds from every culture and grown a rainbow of styles which have taken root and flourished all over the globe.

We are so unique in history. We sometimes have periods of time in which the small minded among us are ascendant but they are always undone by the meanness of their kind and so it will be this time too. Might is not right. We who are the meek will as is said, will inherit.

So turn on your radio and let the music play.

Endure.

Dinner with Branch’s

In answer to some questions about the above post you may click on the link below. Michael Shannon