Los Vatos de Mi Clase y Todas las personas son mexicanas. David Hildago, El Primo.

Sangre de mi sangre…

Los Vatos de Mi Clase y Todas las personas son mexicanas. David Hildago, El Primo.

Sangre de mi sangre…

Page Three

Written by Michael Shannon

A Hobson’s choice is a free choice in which only one thing is actually offered. The term is often used to describe an illusion that choices are available. That’s the military to a “T”

December 3rd, 1942.

At morning roll call, the Lieutenant called your father’s name. He was told to report to headquarters right after morning chow. Like any good soldier he asked what was up and like any good officer the Lieutenant wouldn’t tell him. So after breakfast he hustled over to the headquarters building and reported to the Top Kick, the first sergeant. Hilo would have entered the office, stood on the yellow footprints painted on the floor and announced himself. The sergeant merely looked up then rummaged on his desk until he found what he wanted, then said simply, “Your Orders.” “Where to Sarge?” “Camp Savage, you’d better pack your winter uniforms,” and he laughed.

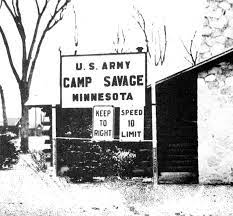

Camp Savage, Minnesota home of the Military Intelligence Service Language School. Camp Savage was a World War II Japanese language school located in Savage, Minnesota, and was the training ground for many Japanese Americans who served in the U.S. military. The buildings were originally built during the Great Depression to house Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) workers. In the rush to build up American forces the CCC tarpaper huts were put into service for the Nisei students. Part of Fort Snelling near Minneapolis, Savage was the new home of the language school. Originally located at the Presidio in San Francisco it was moved to the center of the country for the “safety” of the Nisei students. Californias attorney general Earl Warren a supporter of Executive Order 9066 signed by President Roosevelt on February 19, 1942: this order authorized the forced removal of all persons deemed a threat to national security from the West Coast to “relocation centers” further inland – resulting in the incarceration of Japanese Americans. You will note that the order only mentions “persons,” and not Japanese Americans, though the only removals just happened to be in the west. Germans and Italians weren’t moved anywhere.

Fort Snelling/Savage had a long history controversial acts by the US Government. Snelling is a former military fortification on the bluffs overlooking the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers. The military site was initially named Fort Saint Anthony, but it was renamed Fort Snelling once its construction was completed in 1825.

Before the American Civil War, the U.S. Army supported slavery at the fort by allowing its soldiers to bring their personal slaves. These included African Americans Dred Scott and Harriet Robinson Scott, who lived at the fort in the 1830s. In the 1840s, the Scotts sued for their freedom, arguing that having lived in “free territory” made them free, leading to the landmark United States Supreme Court case Dred Scott v. Sandford. In this ruling, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that enslaved people were not citizens of the United States and, therefore, could not expect any protection from the federal government or the courts. The opinion also stated that Congress had no authority to ban slavery from a Federal territory. United States Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger B. Taney ruled that African Americans were not and could not be citizens. Taney wrote that the Founders’ words in the Declaration of Independence, “all men were created equal,” were never intended to apply to enslaved blacks, they not being “Men” under the laws of the United States.The decision of Scott v. Sandford is considered by many legal scholars to be the worst ever rendered by the Supreme Court. The ruling was overturned by the 13th and 14th amendments to the Constitution, which abolished slavery and declared all persons born in the United States to be citizens of the United States.

The fort served as the primary center for U.S. government forces during the Dakota War of 1862. It also was the site of the concentration camp where eastern Dakota and Ojibway tribes awaited riverboat transport in their forced removal from Minnesota to the Missouri River and then to Crow Creek by the Great Sioux Reservation.

Hilo went down to the transportation office to find out how he would get up to Minnesota, it was nearly 1,400 miles away and when he checked the newspaper in the PX he found out that the high temperature that day was 21 degrees and the low was -1. Not the temperate central California weather where he was from nor even Fort Bliss where it was 68. He reckoned the crack about winter uniforms was good advice. Of course, being the army they weren’t going to issue him any either. He figured he would have to wait until Minnesota.

In ’42, getting from Texas to Minnesota wasn’t easy. The Army would waste no effort in flying a lowly private anywhere, going by car was impossible for those who had them and even if they could get rationed gasoline, that was impossible for an enlisted man. The Army sent soldiers by bus here and there but getting a chit to travel that way was forbidden to the Nisei. With the war in the Pacific the military considered it too dangerous for Japanese Americans travel alone or by private transport. He went by passenger train. Switching railroads and constantly being sidetracked by military trains which had priority, the 1,400 mile trip took six days. He had to sleep on the train car’s benches and jump off at the stations where the train stopped to buy something to eat. Even for a 23 year old in the prime of life it was an exhausting trip although considering what was to come, it was a walk in the park.

He and the other boys kept up on the war news by reading newspapers to pass the time. While they were enroute, the US Navy lost the heavy cruiser USS Northhampton in the Battle of Tassafaronga in the Solomon Islands, sunk by Japanese Imperial Naval torpedos. They read that the Afrika Corps was being pushed into a corner in Tunisia by the Allied armies and their surrender was expected, though that wouldn’t be soon. While traveling to Camp Shelby they read that the US Marines had turned over the mission in Guadalcanal to the US Army which immediately was involved in very heavy fighting in the interior of the island. American and Australian troops finally pushed the Japanese out of Buna, New Guinea. New Guinea was a place Hilo would soon enough become familiar with. Unbeknownst to the travelers, below the bleachers of Stagg Field at the University of Chicago, a team led by Enrico Fermi initiates the first nuclear chain reaction. A coded message, “The Italian navigator has landed in the new world” is sent to President Roosevelt. The result would, in the end, save the lives many Mils soldiers, but that would come much later, too late for many.

Following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, anti-Japanese sentiment and political expediency pushed President Franklin D. Roosevelt to order the army to set up Japanese internment camps in seven western states, that included Japanese Americans who volunteered at the U.S. Military Intelligence Service Language School in San Francisco. The school and volunteers had to move from the so-called “exclusion zone.”

All the western states but Colorado and Minnesota refused to host the school except Minnesota Gov. Harold Stassen who offered 132 acres of land in Savage to host the school. In 1942, Camp Savage was established. An old CCC camp and host to the Boy Scouts, it was run down and primitive. What buildings were still standing were augmented with the building of the cheapest of the military’s building, the loathed and ubiquitous tarpaper shack, the miserable hutment.

Hilo stepped down from the camp bus which had picked up the volunteers at the railroad station. He tossed his barracks bag up onto his shoulder and followed a Corporal who had been sent to get the. When they got to the headquarters building he turned, looked them up and down and over a big grin said, “you’ll be sorry,” followed by a laughter. Names Kobayashi,” he said, “Larry.” “Get checked in and I’ll take you to your quarters.”

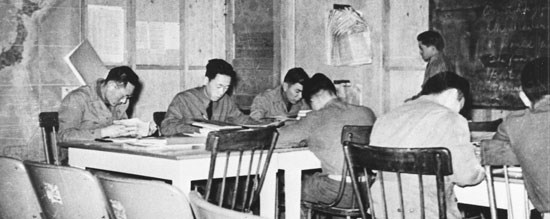

Most of the men experienced for the first time the bitterly cold winter of Minnesota. Nearly all the students were from the temperate zones of the west. Some of the men suffered frostbites and persistent colds. The only source of warmth was the pot-bellied coal burning stove found in the classrooms and in the barracks. The stoves in the classrooms were kept burning by the school staff but the ones in the barracks were the responsibility of the students. If you had been designated barracks leader you usually had to wake up early at 4:30 am. to stoke up the stoves so that the rest of the men could rise and shine in a warmish barracks.

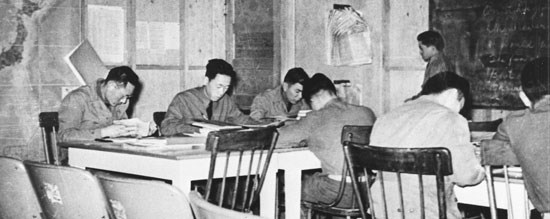

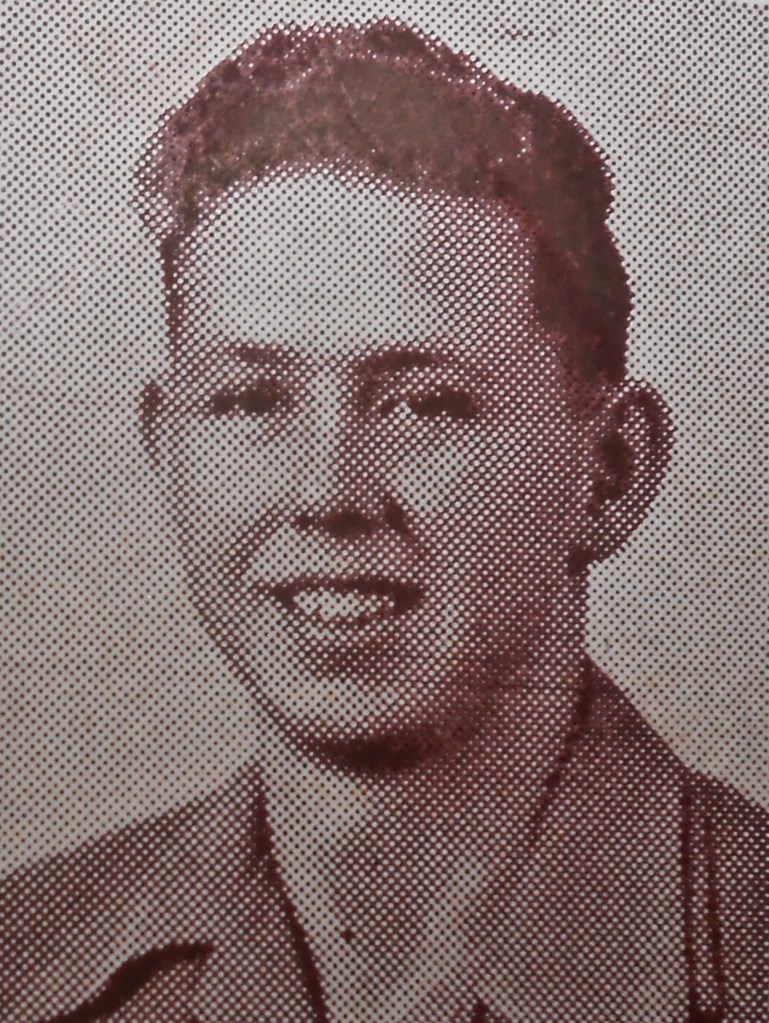

Classmates at Camp Savage. The Military Intelligence Service Language School, 1943. Densho Archive

The purpose of the school was for the volunteers to teach the Japanese language to military personnel. This skill could then be used to interrogate prisoners of war, translate captured documents and aid in the American war effort. A total of 6,000 students graduated from the school before it was moved to Fort Snelling in 1944.

The ancient Chines General Sun Tzu and philospher revered as one of the greatest military strategists, advised in his treatise that intelligence, procured from the enemy is the way to victory. George Washington set up an extensive intelligence system and it really hit it’s stride in the Civil War. Of the two types of intelligence strategic or long term planning and Tactical which concerns the enemy’s strength and location and is used to make immediate decisions on the actual battlefield.

The short but extremely intensive course was designed to meet the demands for linguists from field commanders in the Pacific. The studies included the study or review of the Japanese language, order of battle of the Japanese military forces, prisoner of war interrogation, radio intercept and many other subjects that could be of value in the field. Just to illustrate how intense our course was the kanji (ideographs) instructor would make us memorize seventy five characters a day just to make sure we remembered fifty for the next day’s test. Many of us studied using flashlights under our blankets after lights out at 2200 hours. Saturday mornings were devoted to examinations. Many woke up early, about 0400 hours, went to the latrine, sat on the commodes and studied for the tests under the meager lighting. The competition was so keen in class that the class grade average was in the mid-nineties.

The study week, Mondays through Fridays, consisted of classes from 8 to 12, a brief lunch break, classes from 1 to 5, a break for supper and compulsory supervised study from 7 to 9. Examinations were conducted on Saturday mornings. The soldiers were free from Saturday afternoon until Monday morning. The majority would hurry to the Twin Cities for Chinese food and movies. On Sundays most attended church services in St. Paul, where many students were befriended by a Mrs. Florence Glessner, who graciously invited the Nisei kids to luncheons and parties. Mrs. Glessner was a Red Cross volunteer and after graduation and assignment to the Infantry Divisions on Bougainville, the MIS soldiers made a collection from the members of the language detachments and sent the donation to the Red Cross through Mrs. Glessner. She later sent us a clipping from a Minneapolis newspaper about the donation “from her boys”.

Minnesotans rarely saw any Japanese-Americans and for the most part had little or no racial bias. Unlike the west coast where business and individuals were stripping evacuees of their property, houses, fishing boats and anything they could get their hands on the people of Minneapolis were giving dances and dinners to the kids at school. Showing an appreciation for the Nisei soldiers who were serving their country. Many students at the MISLS were astounded by this. Captain Kai Rasmussen, the camp’s first commanding officer was quoted as saying, “Minnesota was the perfect place because not only did the state have room for the school, but Minnesotans had room in their hearts for the boys.”

Your dad arrived at Savage after your grandparents had already arrived at Poston. It was very hard for them to communicate by mail. Nisei soldiers could not safely write in Japanese and in many cases the parents could not write in English. Letter were very carefully written, in your dads case probably by your aunts, He must have been worried sick about them and they him. They may not have even known where he was. If he got leave at the end of his class he would not even have been able to visit because in 1942, no Nisei soldier would have been allowed in the exclusion zone. When the restriction was lifted in 1944, he had already left for the Pacific war zone.

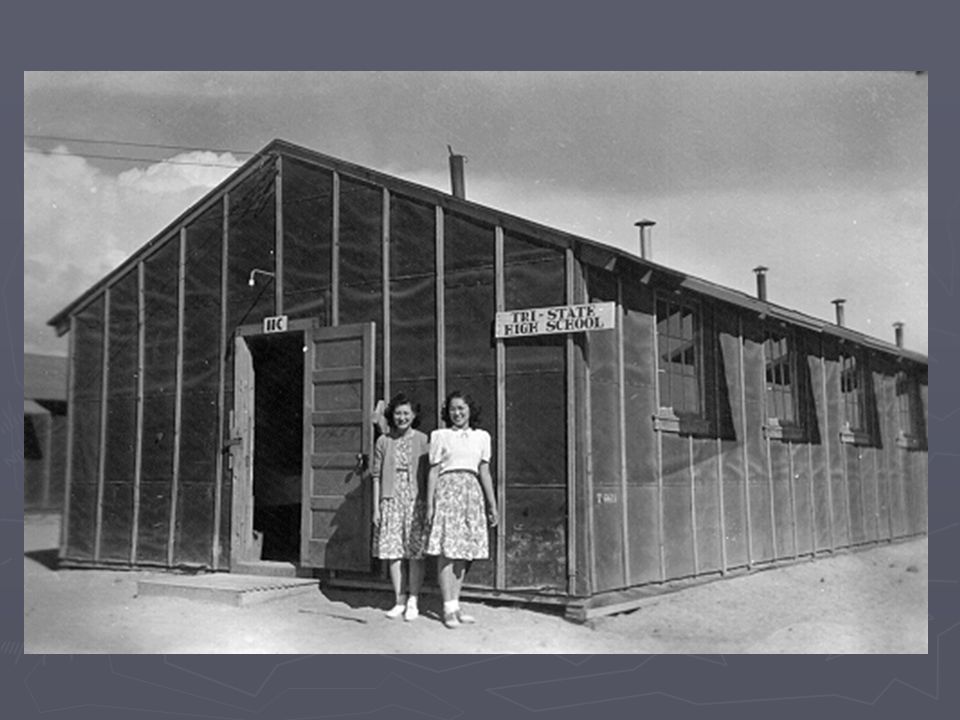

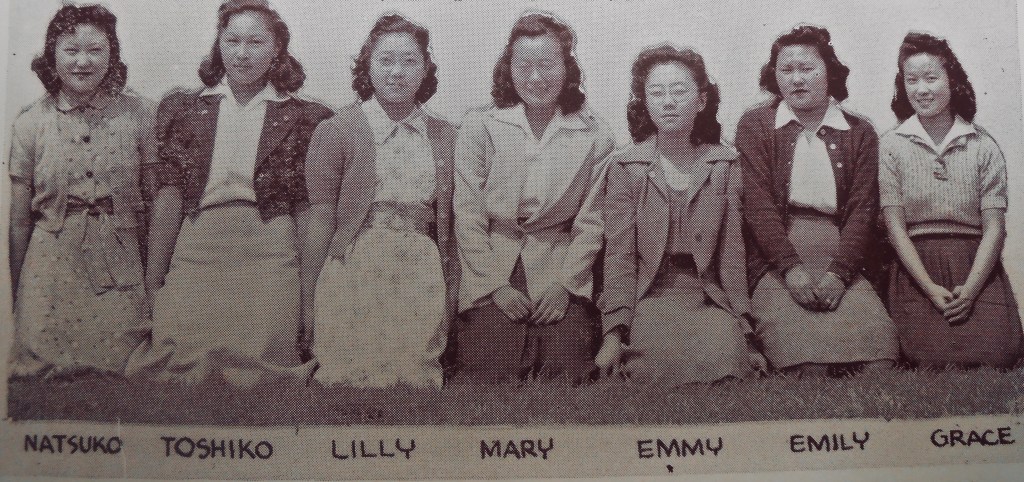

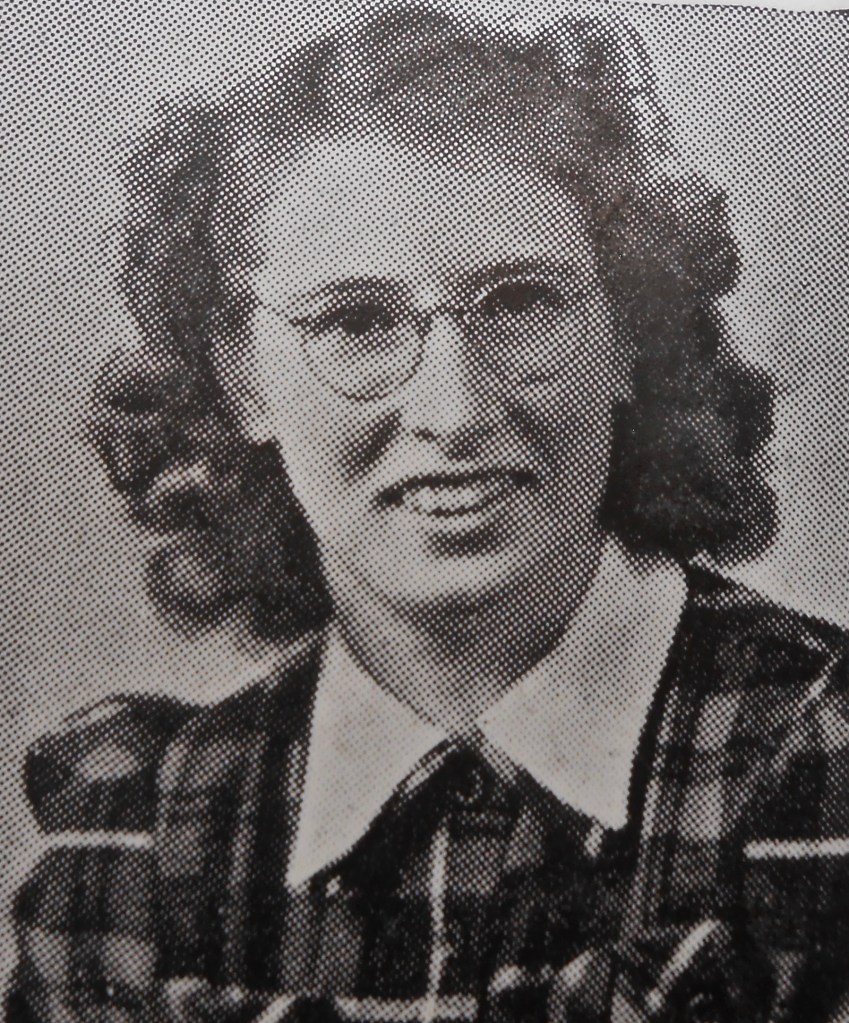

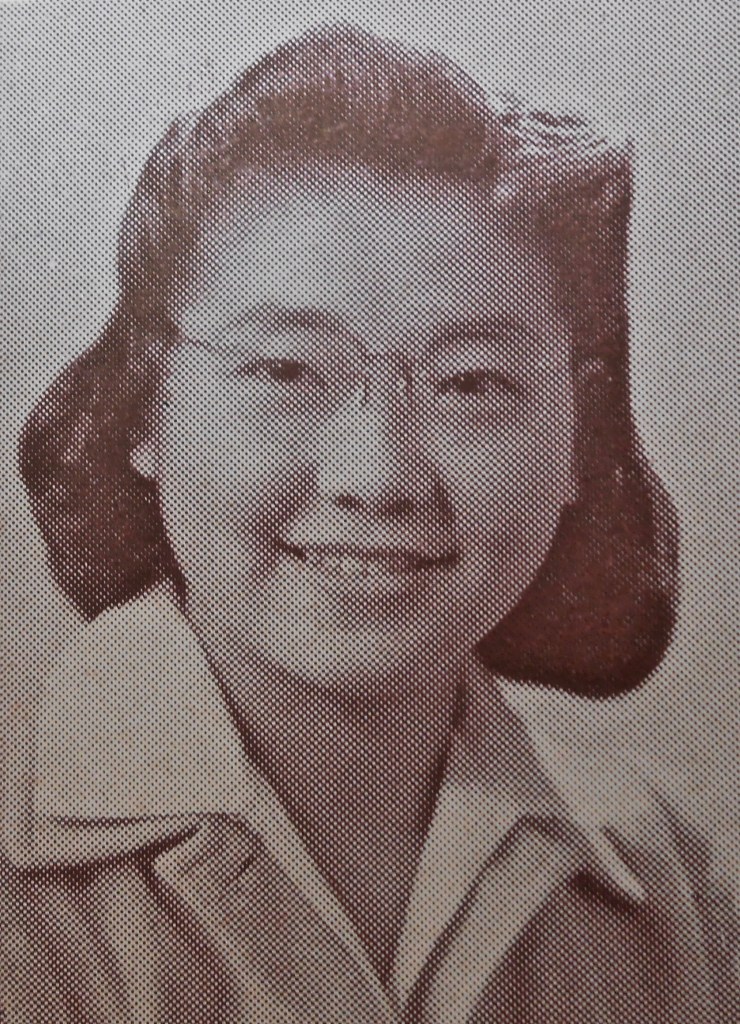

Tri-State High School, Poston Camp. 1943. Densho Archive.

The photo above is a sad commentary, but the two young ladies are a lesson in the girls resilient nature. Though held against their will behind razor wire they still managed to dress in the current fashion of young women. They wear saddle shoes, bobby sox, full knee length skirts, peter pan collars and sweaters, they would not be out of place in any high school in the nation. My mother dressed just like this. She was the same age

It was a rough go for them because almost al the students were from the exclusion zone and many had no idea where their families were. Lieutenant Paul Rusch, one of the senior instructors had spent decades in Japan as a Methodist missionary and knew the culture better than any other instructor. He lent a sympathetic ear. Students said they ween’t angry with the Army but that they were, “Just against everything that was happening with their families. We’re being treated as second class citizens and we hate it.” Imagine what it be like to be forced from your schools and home and cast adrift in a forbidding and alien place where only the most rudimentary life is possible. It was like life on another planet.

A widowed mother with six children in a strawberry field near Fresno. Two of her sons served in Italy and France with the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. She spent the war with her other four children in the Manzanar concentration camp in the Owens Valley of California.

Dear Dona page four

Coming November 8th, 2024

Unlike the American military where mail was censored and journals and diaries forbidden the Japanese Imperial Army thought the differences in language would make ordinary Japanese as indecipherable as any code to an American reader. The head instructors also knew that Japanese soldiers were brutalized by their superiors and would likely be resistant to the treatment the British were using on captured Afrika Corps German troops where violence and intimidation were routinely used. As many of the instructors had lived in Japan for extended periods of time they knew the Japanese were generally very kind and the spirit of co-operation was instilled in them from birth. The culture of Japan was bound to duty to the Emperor and higher authority. They believed that force would not be enough to get prisoners to break down……

Links to other chapters in the series.

Page one: https://wordpress.com/post/atthetable2015.com/12268

Page two: https://wordpress.com/post/atthetable2015.com/12861

Michael Shannon is a writer living in the Central Coast of California. He went to school with many survivors of the camps in his little farming community.

Where the good people live.

Terence John FitzGerald

All the best peopel live here. They care for one another and do for them. Helpful. generous, and loving.

Written By Michael Shannon

Page Two

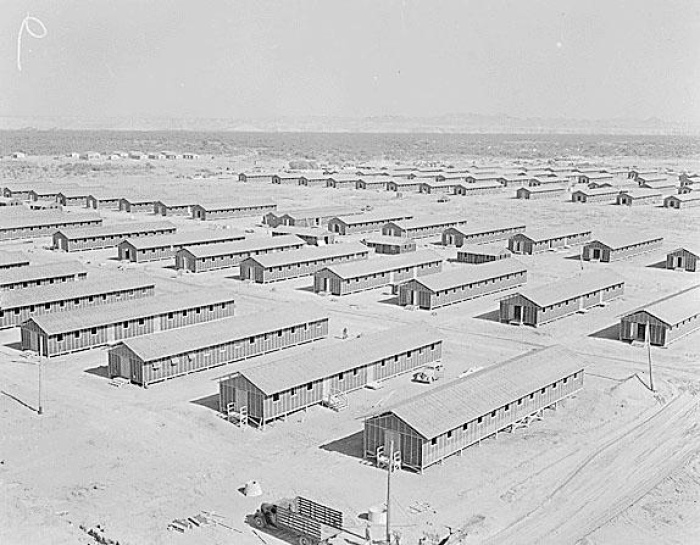

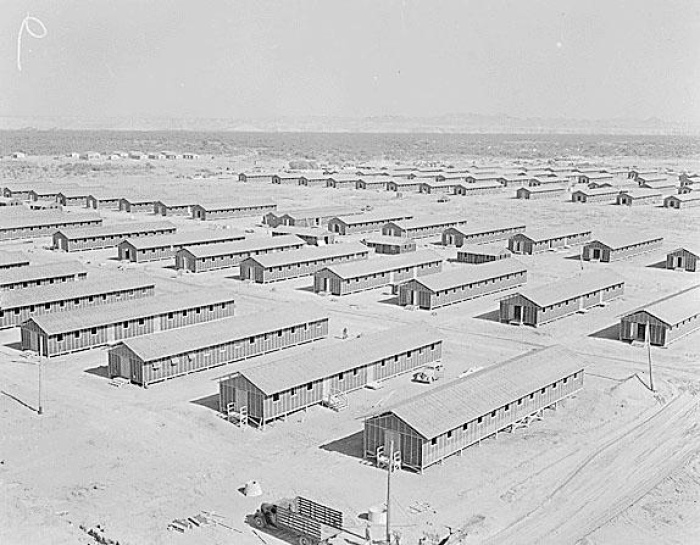

The living quarters of the Poston relocation camp, Poston, Arizona 1943. Pop: 18,000

Poston Camp

Endless rows of tar paper buildings housing six to eight families with no partitions, no toilets, no furniture and no running water. It was 88 degrees in April. They would not see temperatures under 100 degrees until Christmas. The camp was completely surrounded by nothing. No trees, no grass only desert scrub. On top of all that, it was not the worst of the all camps. I have a friend who remembers a little about life there. He was just a small boy from Guadalupe but he does remember the heat. Mothers tried soaking sheets and hanging them inside in the high summer. He said the little kids would run back and forth the length of the barracks purposely running through the wet and slightly cool sheets.

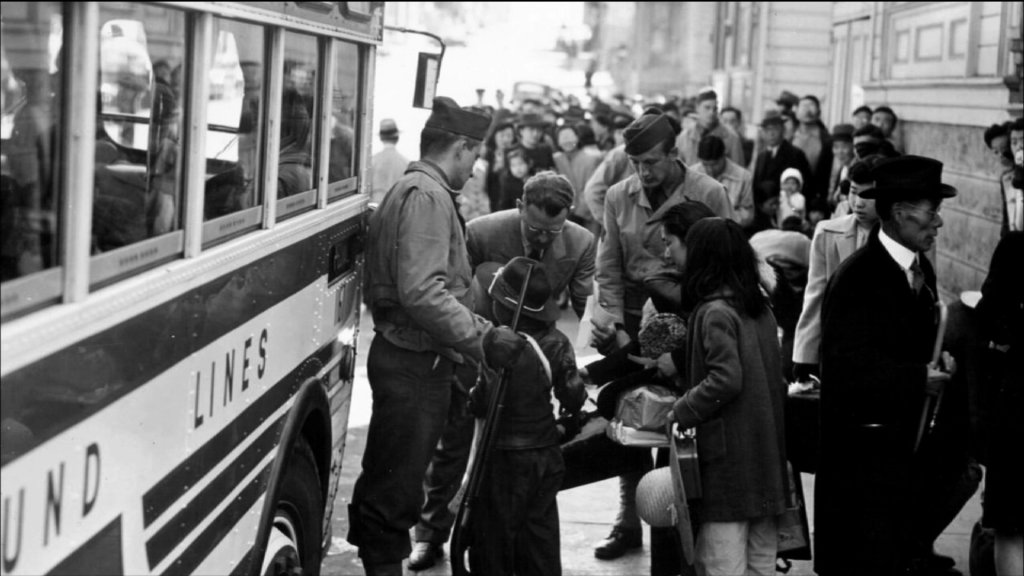

It’s pretty easy to form a picture of your great grandparents taking your dad to the old Greyhound bus depot at Mutt Anderson’s cafe, both wearing their best clothes as they did for important occasions. In 1941 they would have both been wearing hats, he in his Fedora and she with her go to church best, purse on her arm and those sensible heels women wore then. Mom holding a crushed linen hanky in her clenched hand. The family scene is always the same, father looking prideful and the mother just on the edge of tears but holding it all in so as not to embarrass. Hilo would have walked up the steps into the bus and found a seat, maybe at the window so he could look out and see mom and dad. All of them giving a subdued, shy wave as your grandparents hearts broke. Perhaps your mother was there too. My guess is she was.

Boarding the buses April, 1942

I well recall my own parents took me to the Greyhound in San Luis in 1966. My father proud, my mom doing her best to smile but visibly shaking. When the bus pulled out, I looked back to see her fall into my dads arms and bury her head in his shoulder. Just like your grandmother my mother had to go through the leave taking twice.

It is very different than sending a child in peacetime. Then they knew that the devil would take his due and this might be the last time the beloved boy would ever be home again. As always the future was grim and completely unknown.

George, Hisa and Yasbei Hirano with a picture of their son Hirano, Robert; Private; 442nd regimental combat team, 2nd Battalion Headquarters company; killed in action 26 June 1944 at Belvedere, France.

After enlistment your dad was sent basic training at Camp Roberts in San Miguel. He arrived there on the 29th of October and was assigned to Company B of the 82nd Training Battalion for 17 weeks of basic Infantry instruction. He was fortunate. By 1944 boot camp had been reduced to just eight weeks because of the expanding war and the urgent need for new soldiers. Basic is designed to teach you about the Army, it’s history, Its rules and how to operate as a group or groups of many different sizes. Your dad qualified as an expert marksman. He also passed courses in map reading, signals and hand grenade. He learned to fire the 80 mm mortar though he wasn’t assigned to a mortar platoon yet. Guys that weigh 125 pounds are too light to carry them so I’m sure he felt pretty fortunate. He stuck bayonets into canvas bags, fired the fifty caliber machine gun and could disassemble and reassemble his 1903 Springfield rifle with his eyes closed.

Just a week after Pearl Harbor he was headed for Fort Lewis Washington to join Company D, 162nd Infantry. The 162nd was a component of the 41st Division, Oregon National Guard which had been inducted into the regular army in late 1940. The beginning of WWII saw the various state National guards federalized for national defense. Strange as it may seem, the state you were from had little to do with where you were assigned during wartime. It was simply a matter of bodies needed.

While at Fort Washington which is near Tacoma he received further training as a mortar man. The military seems to have a perverse way of surprising you. He qualified as an assistant gunner in February and was re-assigned to the 138th infantry regiment of the Missouri National Guard. The Missourians had probably never met a Nisei since the 126,000 thousand plus Japanese in America were almost exclusively living in the far west, primarily California. One of the great things about the army is the mingling of kids that are from parts of the country where their upbringing and customs are so different. A sort of culture shock takes place at first until they learn that at heart they are not so different. I think you can say that your father like many kids, remember he was just 22, was getting a real education about the country he lived in that didn’t come from any textbook.

The 138th was ordered to Alaska that same month. Going with them would be Private Hiraoki Fuchiwaki, assistant gunner on a mortar crew. Right, a mortar crew for which he was deemed to light too carry. Thats the army for you.

Your dad’s commanding officer was Colonel Archie Roosevelt one of Theodore Roosevelt’s four sons who served in both WWI and WWII. Archie was the only one who survived. Quentin Roosevelt was the youngest son of President Theodore Roosevelt and Edith Roosevelt. Inspired by his father and siblings, he joined the United States Army Air Service where he became a pursuit pilot during World War I. He was killed in aerial combat over France on Bastille Day, 1918. Ted, the oldest died soon after the Normandy invasion. He was a Brigadier General and died of a heart attack while leading his troops. He was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for Bravery. Kermit died after serving in North Africa in action against the Afrika Corps and then fighting the Japanese in Alaska.

I mention the above because the sense of duty people felt was different then. Wealthy, educated and privileged kids stepped up. Sons of bankers (Clair Gibson, Army Air Corps), Judges, (Jim Moore, Navy Seabees) and the well-off who could have wangled a deferment but stepped up to the head of the line. (John Loomis, Marines) The list from Arroyo Grande is long and represented are kids from all walks of life. Grown-ups you knew in school who were your teachers, Del Holloway, Army, Cliff Boswell and Al Sperling, Air Corps, your neighbors, Gordon Dixon, Army, Ace Porter, Army, James Mankins, Army, all three Baxter boys, Don, Bill and Tommy, Navy, Maxine Bruce, Chuck Bells mother and Virginia Campodonico, from the Nipomo clan. Both were Army nurses who served overseas. Your father must have felt the same, that he owed it to his country to serve. He and your uncle were amongst hundreds of young men and women who volunteered from our county.

Many Nisei volunteered out of the camps, the ultimate irony, jailed and held under guard by a suspicious government they nevertheless took it upon themselves to serve a country who didn’t want them.

It wasn’t only the boys either. we wasted the girls and young children, five years stolen from young lives. High school girls with an entire life before them were ripped from school, loaded on buses and taken on the long drive to barbed wire compounds guarded with machine guns. Some would be held until 1948. A single drop of Japanese blood was all it took. Adopted kids went, mixed race kids too. Even white kids raised in Japanese homes. A young man whose mother was half Japanese was at Manzanar. He said because he was mostly white he was allowed to go to high school in Lone Pine where the other kids called him “The Jap.”

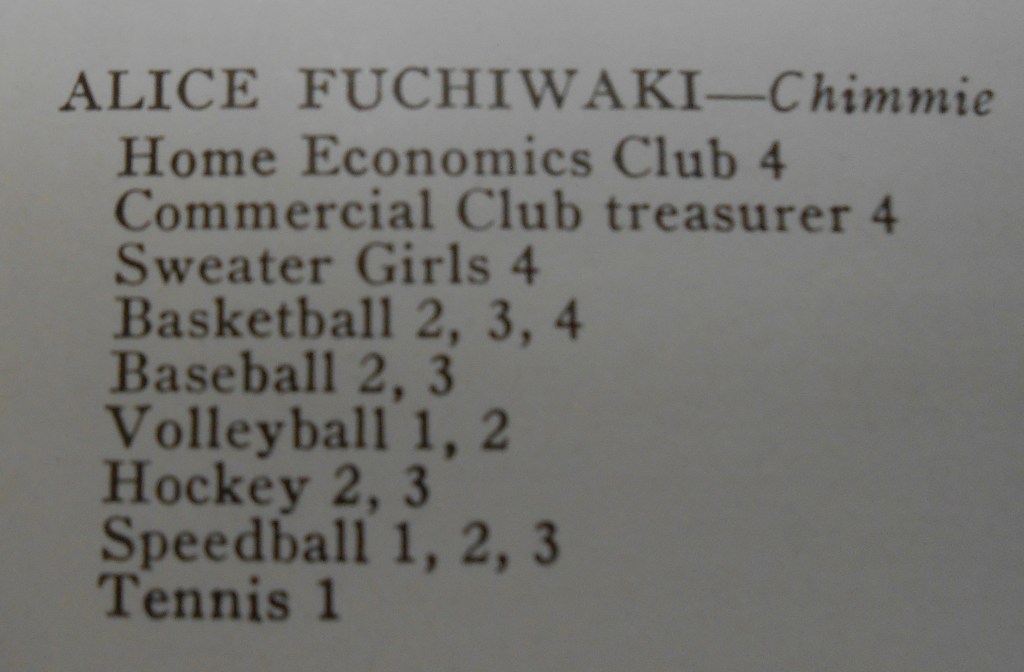

Arroyo Grande High School Graduates class of 1941. Courtesy AGHS

Sixteen or seventeen year old kids of any generation are ill equipped to understand the why of it. The transfer must have been stunning. The Nisei in Arroyo Grande High Schools class of 1941 represented a full 22 percent or more than one in five pupils. Every former student interviewed made a point of saying that there was no bias with the Japanese American kids and in fact they were fully integrated into school life.

Chimiko Alice Fuchiwaki. Prisoner #882, Pima, Sacaton, Gila River camp. Arrived Sept 1, 1942, Departed May 3,1945. She was given an early release to go to Colorado for work. Chimmie never returned to Arroyo Grande. More than half of all the Nisei from Arroyo Grande never returned. The 1943 yearbook had no Nisei grads and almost no boys of any race. The war was in full swing in America.

Called to headquarters just before departure for Alaska your father was given a new set of orders. It was the cold finger of the federal governments Japanese re-location program. Even though neither your father or brother was in camp, they had both enlisted before the war, they are listed as internees in camp documents. There was no escape. When you were on laeave you could only go home, nowhere else. The reaction to the attack on Pearl Harbor was a disaster for the Japanese on the west coast. The war department had suspended enlistments from the Nisei and was pondering discharging all soldiers of Japanese decent. In the meantime they were withdrawn from their units and essentially parked at army bases in the middle of the country until it was decided what to do with them. Your dad was sent by train to Fort Bliss, Texas. He traveled along with other Nisei soldiers on trains with window shades drawn so as to not draw any attention to them. Fort Bliss was the perfect place. Located in West Texas just north of the Mexican border you can hide anything in its 1.12 million acres of scrub desert in El Paso County.

At the time Fort Bliss, was an old Cavalry base dating to post Civil War, it still had a barracks named for Robert E Lee. Don’t forget that Texas was part of the Confederacy. Run down after two decades of governmental neglect, it held a hodge podge of military from the “Old Ironsides” 1st cavalry division (Armored) to Nisei units waiting to be shipped to Mississippi for infantry training with the 442nd or up to Minnesota to the language schools. Afrika Corps POW’s were also interned there right next to Japanese Americans held in concentration camps. The Japanese were behind barbed wire, the Germans were not. Some irony there.

The 138th’s experience in Alaska was a disaster and your dad was extremely lucky to have missed it. Deployed to the island of Kiska in the brutal cold and perennial fog, the new and untried soldiers saw shadows everywhere. One dismal night of combat saw thirty soldiers killed and fifty wounded all by friendly fire. The Nisei soldiers were justifiably terrified of being shot by their own comrades. It was soon apparent that the Japanese had evacuated the island before the 138th had even arrived. Diaries and un-mailed letters left behind and read by MILS interpreters made it clear the Japanese soldiers hated the war and wanted to go home. So did the Americans. Operation Cottage was a dismal failure. General Simon Bolivar Buckner Jr. who was in charge of the Alaska campaign said, “The invasion of Kiska was a great big, juicy, expensive mistake.” General Buckner would cross paths with the Nisei and the MILS again in the far Pacific in 1945.

138th regiment, mortar crew, Kiska Island, Alaska. 1942 War Dept. photo

Assigned to random make work duties the Nisei soldiers had no idea what their fate would be. Back home their families were packing their one suitcase of belongings and preparing to be bussed out to holding centers where they would await their assignments to the infamous relocation camps where they were destined to spent the war. Your grandparents and your aunts were taken to Tulare where they were housed at the county fairgrounds, keeping house in dirty old horses stalls. Everything they had other than the one suitcase was left behind to be stolen or destroyed by vandals. Neither of their sons could do anything to help. It must have been agonizing. As soon as the half completed camps were ready, your grandparents and your aunts were taken by train to Poston, Arizona and then trucked to the Gila River concentration camps. They at least were able to see friends from Arroyo Grande, the Saruwataris, Kobaras, Hayashis, Ikedas, Fukuharas and the Nakayamas were all there. They would have to make a new life there. They could no longer dream of a future. They would have to bear what could not be born. ( Shikata Ga Nai )

After eight months in Texas, he and the other Japanese boys were ordered to a barracks building where an officer with the Military Intelligence Service presented an opportunity to leave Fort Bliss. He said the army was looking for soldiers who had knowledge of the Japanese language. Could they speak it, or write it? Had they spent any time in Japan attending Japanese schools? The army had figured out that since they had no one who could speak or write Japanese they were going to be at a great disadvantage when they began their cross Pacific advance where the were sure to have captured Japanese soldiers and workers.

Those who could were encouraged to apply to the school and take a test which would qualify them for jobs as interpreters in the Army’s Intelligence Services.

Both your dad and uncle spoke, read and wrote Japanese. Your grandmother is listed as a Japanese speaker on her census forms so Japanese was spoken in the home. They both qualified as speakers and it’s very likely they attended the old Japanese school off Cherry Lane. They would have gone there after school to study reading and writing and the customs and history of Japan. How seriously its hard to say. In some of my interviews there was a lot of laughter about how serious they were. As one man said, “We hated it, we were American kids after all, not Japanese,” but we had to go.

For the Fuchiwaki boys it was to pay off. Ben was already at Presidio in San Francisco studying at the Military Language Institute while Hilo was in Texas being bored. Volunteering is simply not done in the military, at least not often. Soldiers know better. The thought is, if you volunteer for a duty you want, the army will make sure you never get it. But it was Texas, flat, dusty, desert Texas at that and if volunteering might get them a transfer and out of there, why not? The thinking was that at least it could turn out to be an important job.

All the candidates who volunteered were whisked off to an empty barracks building and spent two grueling days test taking. They were tested on the spoken word; They were tested on reading and writing and finally at the end, a sit down interview by a senior enlisted man from the language institute. White officers were present but not as interviewers because the Army only had a very few who had any fluency in Japanese at all. The interviewers were enlisted, non-officers because it was Army policy that no Japanese Americans could rise above the rank of Sergeant. At the time all Nisei units were commanded by white officers.

Your dad would have had no real idea of how he did on the tests. The military rarely gives a grade to the one taking any test. So, they waited….and waited, and waited some more. Some volunteers waited weeks before they were called in for final interviews. The waiting was just the military way. It was and is something that sailors, Marines and soldiers soon get used to. “Hurry up, and wait” has been the way since long before Alexander the Great. Never changed, never will.

As time passed, the Nisei soldiers began to see what their future might be. It had become common knowledge that because of manpower needs the War Department had decided not to discharge the Nisei but to incorporate them into new, all-Japanese units which would eventually be sent to the European theater and in particular Italy thus solving the issue of Japanese Americans fighting the Imperial Japanese.

The 100th Infantry was the initial unit which was made up of Nisei boys from Hawaii and the west coast who had been enlisted before Pearl Harbor. Later, the 100th would be integrated into the 442 Regimental Combat Team which did see terrible combat in the climb up the boot of Italy. The 442nd was to become the most decorated small unit, ever, in US Army history. Those kids felt they had something to prove and they laid down their lives by the thousands to do it. As happens in wartime, hard fighting units are “used up.” They are sent into combat again and again until they are ground down to nothing. Such it was with 442nd. A difficult objective and they were first in line. Their patriotism and the racist general who was their commander who was looking for promotion from his own superiors guaranteed that.

Your dad, if accepted in the language program might be spared combat for the time being, Nisei troops were already being sent for combat training. For one year, the men trained at Camp McCoy in Wisconsin and Camp Shelby in Mississippi. In May 1943, the 100th participated in training maneuvers in Louisiana. That August, the 100th deployed across the Atlantic to the Mediterranean where they took part in the Italian campaign. The men selected the motto “Remember Pearl Harbor,” to reflect their anger at the attack on their country. In Hawaiian slang they said, “Go For Broke.” They did just that too.

Hardly anyone here remembers that but when I lived in Hawaii just two decades after the war, those soldiers had used the GI Bill to go to college. They ran the unions and the banks. They were college professors and business owners. The Nisei had gone from the cane fields to the corporate office in one generation. “Go for Broke” they said and they did.

Dear Dona

Page Three

Hobson’s choice is a free choice in which only one thing is actually offered. The term is often used to describe an illusion that choices are available. That’s the military to a “T”

December 3rd, 1942.

At morning roll call, the Lieutenant called your father’s name. He was told to report to headquarters right after morning chow. Like any good soldier he asked what was up and like any good officer the Lieutenant wouldn’t tell him. So after breakfast he hustled over to the headquarters building and reported to the Top Kick, the first sergeant. Hilo would have entered the office, stood on the yellow footprints painted on the floor and announced himself. The sergeant merely looked up then rummaged on his desk until he found what he wanted, then said simply, “Your Orders.” “Where to Sarge?” “Camp Savage, you’d better pack your winter uniforms,” and he laughed……

Coming November 2nd

Link to Dear Dona page one: https://wordpress.com/post/atthetable2015.com/12268

The writer is a lifetime resident of Arroyo Grande California and writes so his children will know the place where they grew up.

Written By Michael Shannon

Page One

Saturday, October 19, 2024

Dear Dona,

Something in your note about not knowing what your dad did in WWII struck a cord. I have some research from the Manzanar story so I though I’d look into your dads service in World War two.

Most people have very little or no knowledge of the Japanese Nisei experience. I’ve interviewed people of that generation who had no idea that there were Nisei soldiers at all. In fact, there were none in the Navy, Marines or Air Corps, only the Army and its nurse crops accepted Nisei and only citizens at that.

I’m sending you this to pass along what I found about your dad’s service. One of the complaints of military men is the constant record keeping they must do. The funny thing is that once they are separated from the service the records go who knows where. Perhaps they are stored in cardboard boxes at the back of the warehouse pictured in the first Indiana Jones movie. Who knows? In any case some can be found in order to fill in a family’s story. In a way its a treasure hunt. There can be quite unexpected results. In fact its like assembling a puzzle when some of the pieces are missing.

The difficulty for children is that wartime veterans are extremely hesitant to tell them what their experience was like. There are a few reasons why that is so. One, the kids have no background experience or education to make much sense of it. Two, in the case of combat veterans, the stories are too horrible to contemplate telling your own children. Third, their hope is, that surely the kids will never have to experience their fathers hell for themselves.

Most sons and daughters of veterans never hear much about the parent who actually served. In WWII, somewhere around 12% of all regular army soldiers saw combat in which their was actual shooting. The average combat soldier was involved in combat for a period of around forty days. By comparison soldiers in Viet Nam averaged 240 days and in Afghanistan close to 1,200 days. The difference wouldn’t matter to your father. One day at a time is how it’s done.

Your father saw active combat against the Japanese Imperial Army on the islands of Luzon in the Phillipines and went in on the first wave in the invasion of Okinawa. The battle for Okinawa drug out over nearly three months, from April 1st until June 22nd 1945.* Okinawa was the last major battle of World War II. It was the bloodiest battle in the Pacific War. It involved 1,300 U.S. ships and 50 British ships, four U.S. Army divisions, and two Marine Corps divisions. The U.S. objective was to secure Okinawa, which would remove the last barrier between U.S. forces and Imperial Japan. By the time Okinawa was secured by American forces on June 22, the United States had sustained over 49,000 casualties including more than 12,500 men killed or missing. The fighting was absolutely vicious with the Japanese fighting to the last man in most cases. The battle caused more than twice the number of American casualties than the Guadalcanal Campaign and Battle of Iwo Jima combined, with the Japanese kamikaze effort causing the American Navy to suffer more casualties than any previous engagement in the Atlantic or Pacific. The Navy suffered the greatest loss in its history.

The U.S. Navy lost 32 ships and aircraft, and 368 ships suffered damage during the Battle of Okinawa, . The U.S. Navy also lost 49,151 sailors, with 12,520 killed or missing. The Japanese by comparison lost more than 110,000 military personnel killed, and more than 7,000 were taken prisoner during the fighting.

The number of Japanese surrenders was unusual for the Pacific war. Most of the credit must go to the personnel of the Japanese American members of the Military Intelligence Language Service or MILS as it was known. Both your father and uncle were members and attended the Army’s Japanese language schools.

So how did he get there. The answer is multifaceted and complicated because as always anyone history when its being written is like a juggler trying to keep too many balls in the air..

When I was researching the series on Manzanar I used, as my primary sources two Japanese American archives which were put together after World War two and have grown year by year ever since. Collected were diaries, letters, newspapers and radio news, family photos and most fascinating; oral histories by a very wide cast of characters. Generals, politicians, researchers and thousand of ordinary citizens who lived through the concentration camps.

When I talked to people in that generation, many whom I knew personally, I learned that the community, the community of the same age, those in high school or younger who were coming of age in the late thirties lived quite a different life than many might imagine. What they though about one another was different than the preceding generation.

Looking through the old yearbooks from that time it’s easy to see Nisei kids were completely integrated into teenage life. Sports and clubs, social events all featured mixes of kids from all backgrounds.

My dad was a scoutmaster in the late thirties and kids like Haruo , Ben Dohi, John Loomis, Gorden Bennett and Don Gullickson along with my father told me funny stories about camping together and there wasn’t a hint of any racism. Stone went to HS with my father and was a life long friend. Personally, I don’t think it ever occurred to me that Leroy or Masaki was any different than I was.

Quite obviously there was discrimination by older folks and would be a great deal after Pearl Harbor but amongst those kids who who were in or just graduated in the years before the war there was little. Contemporary accounts in the local papers list Nisei kids names in all the kinds of chatty articles written about the goings on of youth. My fathers Boy Scouts listed the names of many Nisei kids and interviews with them showed me that they were friends no matter their skin. It strikes me that that generation saw little difference amongst themselves. They spoke the same high school language, they dressed alike as kids do, they combed their hair the same. Nisei boys played baseball, football and basketball together and as now, kids for the most part supported each other against the machinations of adults.

My own experience as a high school teacher illustrates my point. Adults, teachers and administration might publicly dislike your style of dress, or how you wear your hair but the kids themselves will put up a united front against any perceived transgression into the territory they reserve for themselves. You yourself will remember girls climbing the trees at school to protest the dress code. I’m sure ethnicity had nothing to do with that because kids unite over things they find unfair. Your dads friends would have felt the same.

A case in point, I never heard a disparaging remark from any adult I knew who went to school with your dad, uncle or any other Nisei because they knew who they were. They weren’t “Japs,” they were friends. That foul term was reserved for the Imperial Japanese, not friends.

When your father graduated from Arroyo Grande High School, the old brick one on Crown Hill in 1936 the Japanese Imperial army had invaded Manchuria and was moving into China, the Rape of Nanking was the next year. Mussolini, 1928 had annexed Libya and in just the year before your dad’s graduation had instigated the war in Ethiopia where he used poison gas, tanks and air power against tribal armies armed with old muskets and spears. Hitler had opened the first concentration camps in 1933, just one year after he was elected to office. In little Arroyo Grande all of this would have been news. Radios and newspapers published world news. Young men were not much concerned I’m sure about all of this conflict, it was worlds away from the lives of rural farmers. was the possibility of war. Arroyo Grande was far, far away from world events.

The next three years would mean a great deal to the lives of the young and as events were to prove, terrible things to the were coming to the 126,948 people of Japanese ancestry in the United States, 74% of whom lived in California.

Crown Hill High School, 1941

Your dad graduated Arroyo Grande HS with the class of 1936 and was working for your grandfather until late 1941 when he decided to follow your uncle Ben into the service. He was inducted on October 31st, 1941 just a little more than a month before the attack on Pearl Harbor. No one knew that was coming of course but by that time the German army along with their allies the Italians had overrun France, Holland, Belgium, and most of western Europe, They had occupied Norway and were advancing on Egypt in north Africa. Greece was under Nazi control and most of eastern Europe as well. German submarines were slaughtering ships transporting material to Britain in the north Atlantic. On the 2nd of October the German army launched operation Tornado which was a continuation of the previous years invasion of Russia.

In the far east the Imperial Japanese army had invaded and conquered Manchuria and was steamrolling across China. The general staff in Tokyo was in the final stages of planning for the surprise attacks that were to come at Pearl Harbor, the Phillipines and the rest of Southeast Asia.

No one in the United States could have possibly missed the threat to the country by these events. On October 17, 1941, the German U-boat U-568 torpedoed and damaged the destroyer USS Kearny off Iceland, killing 11 and injuring 22. The day your father raised his right hand in Los Angeles and swore to defend his country disaster struck in the early morning hours in the north Atlantic. While escorting convoy HX-156, the American destroyer U.S.S. Reuben James DD-245 was torpedoed and sunk with the loss of 115 of its 160 crewmen, including all the officers.

The draft had been instituted by congress in September of 1940. Called the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940, it required all men between the ages of 21 and 45 to register for the draft. This was the first peacetime draft in United States’ history. Those who were selected from the draft lottery were required to serve at least one year in the armed forces. Once the U.S. entered WWII, draft terms extended through the duration of the fighting.

Although the United States was not at war at the time, many people in the government and in the country believed that the United States would eventually be drawn into the wars that were being fought in Europe and East Asia. Isolationism, or the belief that American should do whatever it could to stay out of the war, was still very strong with almost half the Americans polled saying we should stay out. But with the fall of France to the Nazis in June 1940, Americans were growing uneasy about Great Britain’s ability to defeat Germany on its own. Our own military was woefully unprepared to fight a global war should it called upon to do so.

The first number drawn in the 1940 U.S. draft lottery was 158, which was announced by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on October 29, 1940. Your father along with your uncle must have thought that it was better to volunteer than wait. The thinking at the time was that it was better to have some choice in where and when you served than be at the mercy of a blind system of quotas.

Hilo registered in Arroyo Grande on the 16th of October 1940. He may have waited to be called up because of your grandparents. Under the exclusion act they were not allowed to own land or a home and so like most Isei, rented. The land below the Roosevelt highway in the Cienega where they farmed and lived was rented. For tax and census reasons your uncle Ben was listed as the head of the family though he was just 24. I’m sure that was all just on paper though. Your grandfather certainly ran the show since with only your aunts left at home he was able to continue farming for the next five months until they were hauled off to Tulare and then to Poston, Arizona on the Gila River, the concentration camp where they and your aunts remained until 1945

the Poston concentration camp, Gila River, Arizona where most of the Arroyo Grande citizens where held.

Your father reported for active duty in Los Angeles on the 23rd of December 1941. There he took the oath to defend the constitution of the United States from all enemies foreign and domestic. Five months later his family was locked up behind barbed wire and held inside by soldiers armed with rifles and machine guns.

Name Hiroaki

Race Japanese

Marital Status Single, without dependents (Single)

Rank Private

Birth Year 1917

Nativity State or Country California

Citizenship Citizen

Residence California

Education 4 years of high school

Civil Occupation Farm hands, general farms

Enlistment Date 23 Oct 1941

Enlistment Place Los Angeles, California

Service Number 39167146

Nisei men reporting for Army induction, 1410 East 16th Street Los Angeles, CA, 1941

Page Two

Coming on October 26th, 2024

It’s pretty easy to form a picture of your great grandparents taking your dad to the old Greyhound bus depot at Mutt Anderson’s cafe, his parents wearing their best clothes as they did for important occasions. In 1941 they would have both been wearing hats, he in his Fedora and she with her go to church best, purse on her arm and those sensible heels women wore then. The family scene is always the same, father looking prideful and the mother just on the edge of tears but holding it all in so as not to embarrass. Hilo would have walked up the steps into the bus and found a seat, maybe at the window so he could look out and see mom and dad. All of them giving a subdued, shy wave as your grandparents hearts broke. Perhaps your mother was there too. My guess is she was………..

The writer is a lifetime resident of Arroyo Grande California and writes so his children will know the place they grew up in.

Michael Shannon.

Friday the Philadelphia Phillies were out west playing the Los Angeles Dodgers at Chavez Ravine. Philadelphia brings not only coaches and ballplayers to your park but a well deserved reputation for hard-nosed baseball. Actually, hard nosed period.

Philadelphians are known for their distinctive affinity for their home sports teams. Philadelphia sports fans have quite the reputation. From “burning down the city” to dragging down opposing team’s enthusiasts, fans of the city’s national sports teams are constantly criticized for their ornery nature. There is something to be said about “throwing all your hopes and dreams” into something that you have no impact on.

Don’t tread on me. Nick Castellanos. ESPN

Founded in 1883, the Phillies are the oldest, continuous, one-name, one-city franchise in all of professional sports and one of the most storied teams in Major League Baseball. Since their founding, the Phillies have won two World Series championships (against the Kansas City Royals in 1980 and the Tampa Bay Rays in 2008), eight National League pennants (the first of which came in 1915), and made playoff appearances in 15 seasons. The team has played 120 consecutive seasons and 140 seasons since its 1883 establishment.

The sports website Bleacher Report ranked Phillies fans as having the “most insufferable fan base” in sports. A tough blue collar city Phillies fans revel in that particularly the “Insufferable” part. My friend Jim, who’s from Philly says no one in Philadelphia has ever used that word in a sentence. Just more ammunition to hate highfalutin, self satisfied fans from other cities. Letting the air out of other teams balloons is the Philadelphia national sport.

My son and I watched the game and saw, perhaps the application of a little Voodoo. Gris-Gris personified. A Doctor John example of a talisman, amulet, voodoo charm, spell, or incantation capable of warding off evil and bringing good luck to ones team while bringing misfortune to another, the Dodgers in this case.

The outfield camera was looking in towards home plate and just to the left of the catcher a middle aged blonde woman carefully lifted a small box with a glassine cover. She deliberately turned the transparent part towards the camera and if you looked closely you could see that inside was bobblehead doll, a Chase Utley bobblehead in a Dodger uniform. Yes, that Chase Utley, the one that played 12 years at second base for the Phillies, a perennial all-star and quiet team leader. He was perhaps the steadiest leader of the Phils since Hall of Famer Mike Schmidt. A man you could build on, a man you could admire, a man who upheld the fans notion of a true Philadelphia Phillie, tragically traded away for money to those wretched old Trolley Dodgers who now resided in that west coast city, den of iniquity, land of the Lotus Eaters, Lost Angeles. Phil’s fans were surprised, hurt and then angry. Really angry, really, really angry.

Take that. SSI photo

Fast forward to 2024. As the woman, her face twisted with a kind of glee you might see on the face of a righteous believer waggled her little box timing it to the time the camera waited for the pitcher to deliver the ball to home plate. Her companion monitored the TV feed on her Cell phone so she knew when the camera man was focused on her antics.

With a demonic look she stared straight into the camera and slowly puled the little doll out of the box, holding it so its little painted eyes looked straight into the lens and then reached up with her right hand and slowly, ever so slowly twisted poor Chases’s little head clean off. Getting to her feet she turned back to the crowd and raised the headless doll up high and the turning back to the camera, slam dunked the poor little deceased thing to the concrete. With an obviously demonic laugh she sat back down and shared a high five with her companion, the spell complete.

Phillies 6, Dodgers 2.

J T Realmuto vs Chris Taylor. AP

Dodger management needs to find that woman, she is quite clearly the reason the Dodgers have more players on the injured list than in the dugout.

Gonna have to go through this guy first, seriously.

As you can see the writer is a fan.

Michael Shannon is what was once known as a baseball Crank. Baseball can save your sanity. Try it.

By Michael Shannon

Mundane things. Sitting on the kitchen table, arranged and seemingly haphazardly set. Salt and pepper shakers, the old milk glass kind with the screw on top, the salt perpetually stuck to the top. There is a sugar bowl with no top. The top wasn’t necessary because my father in particular was very partial to a good coating of white sugar on all kinds of things. Sliced tomatoes received a liberal coat of sugar as did his already sweetened cereal. Habits from his childhood when nothing you might eat was sweetened. He told me once that a real treat in late teens was to slice a piece of bread, there was no sliced bread in 1920’s Arroyo Grande, you had to do it yourself. You then spooned whipped cream over it. When your parents own a dairy you soon learn that there is nothing that cannot be improved by a liberal coating of cream. In our house, Pumpkin pie must be completely covered and invisible. If not, it’s simply inedible.

Old copies of the Los Angeles Times, and the San Francisco papers held sway in our household, conservative to the core he said. The news was mixed with the occasion Redbook or Ladies Home Journal and sat haphazardly near the corner of the table where nobody ever sits. At my mom’s end is an old Signal Oil ash tray courtesy of her fathers long career as an oilman. You may remember the kind with bag of buckshot to keep it in place. I know it was shot because I made a hole in it one day when know one was looking. My dad just uses a handy plate or if nothing else, the turned up cuff of his Levi’s.

This place of honor, pride of place thing, was reserved for a book. Over the years there was a succession of them, one after another. They were always dog eared with the ubiquitous coffee ring and the occasional petrified Cheerio courtesy of my little brother Cayce who ranked amongst the worlds fastest eaters. Mornings he could be seen surrounded by a halo of Rice Krispies or Cheerios carried on a mist of milk drops. He had the digestive tract of a buzz saw. He needed that because he was chronically late. Dad always said he needed that because he could leave the house at 7:05 and be at work in Pismo Beach at 6:50. It was a unique talent, not many people can make time run backwards. The only documented person other than my brother was Emmett “Doc” Brown.

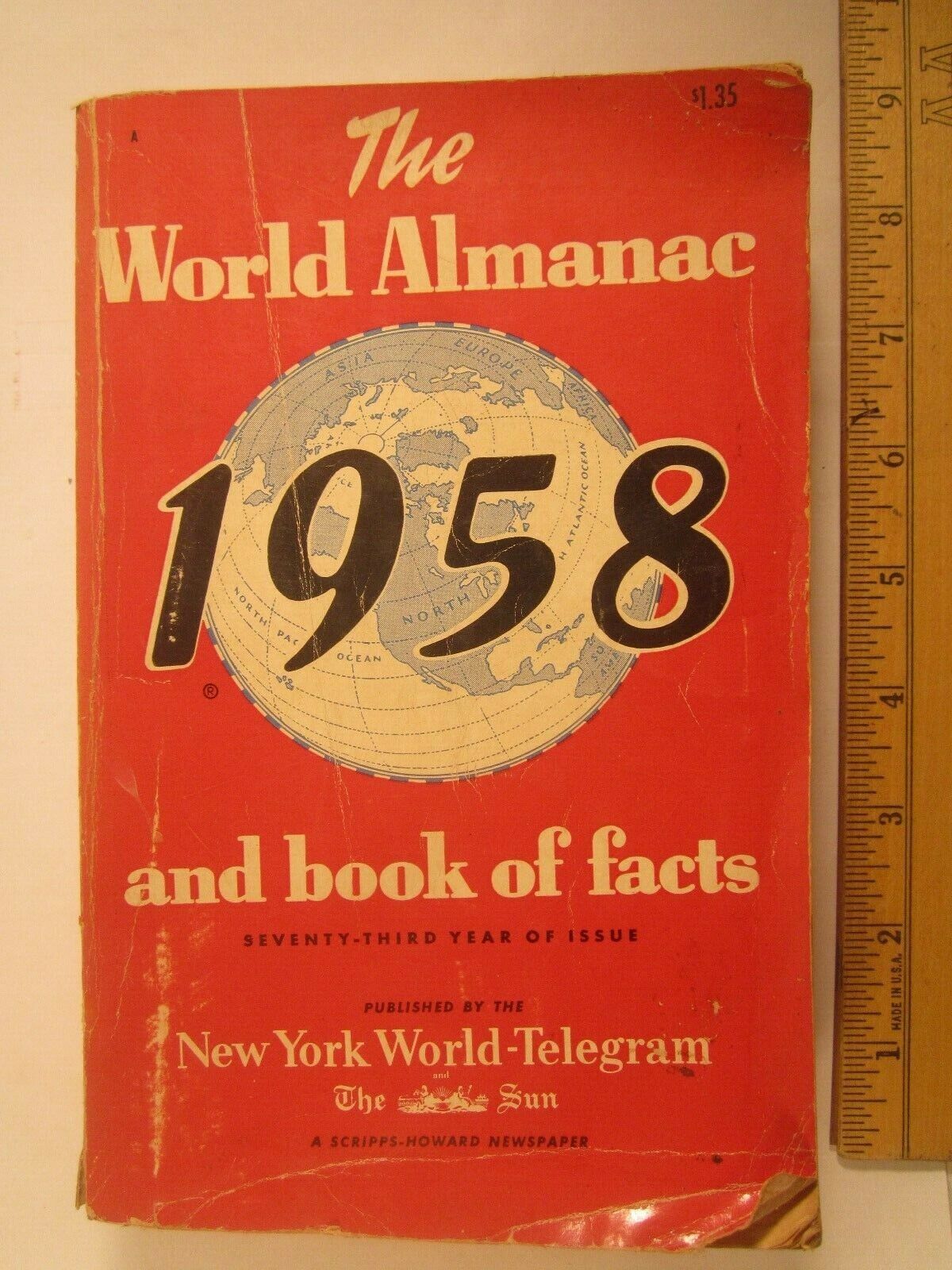

The book, which sat at my fathers right elbow was the World Almanac. More of our basic education came out of that book than our textbooks. The number one thing was the satisfaction that came from knowing a fact. The things our teachers taught us at school were in great part just things to memorize. Nearly any disagreement or argument on almost any topic could be settled by thumbing those tissue thin pages until the correct answer appeared. As a child it seemed simply magical.

Today an actual Almanac is hard to find. The local library has one in the reference section but you cannot check it out. There are many search engines but they are fraught with misinformation. You can’t step into the jaws of Google unless you’re armed with the skills necessary to dig through that pile of trash in order to find the nugget at the bottom. The totality of Google is simply unknowable. With a book you can see every part, turn that page and read facts that have been researched, checked and rechecked. Gird your loins with a good education and enter the fray if you will.

Dad would pose random questions about almost any subject and the kids would make wild guesses about the probable answer. Out would come the Almanac. He opened a courucopia of questions because we soon learned that there is never a simple answer. Behind every answer there is still another question.

So, how far west can you go in the United States? Well there is Port Orford, Oregon (Port Awful if you are an Oregonian) is the westernmost incorporated city in the contiguous US. Ok, but is it the actual westernmost point? No it’s not, that honor goes to Cape Alava, Washington. But, there’s more. What about Alaska and Hawaii? Honolulu is 7.954 degrees of Longitude farther west than Anchorage. With one degree being 69 miles that equals about 550 miles. Surprise, surprise as Gomer would say.

It gets even more mind boggling. Point Udall, Santa Rita, Guam is the westernmost point of all in the United States and it’s territories. But wait, it gets even better, Point Udall, St. Croix, US Virgin Islands is the easternmost point. They are 9,541 miles apart. How does that make any sense? The two different Point Udalls are named for two different men: Morris, “Mo,” Udall (Guam) and Stewart Udall (Virgin Islands). They were brothers from the Udall family of Arizona. They both served as U.S. Congressmen, both liberal Democrats and environmentalists in the 60’s and 70’s. Perhaps the names indicate the distance from conservative Republican Washington politicians as you could get. Look them up in the almanac, they were interesting men.

We looked up populations. How big was New York in 1880? How about now? What is California measured in Square miles? (163.695 ) We were surprised to learn that our state is larger than Italy, Germany, England and Japan. Our home county is only a few square miles smaller than Rhode Island and Delaware combined.

Like a reverse telescope you could look back and find countries that no longer existed or had changed their names. Kind of like Grover City which is now Grover Beach though there is no beach in Grover. My dad made sure we knew that real estate people can be pretty good at pulling the wool over your eyes. The actual source of that phrase is unknown. The expression was first recorded in America in 1839, it’s thought to be of much older, English origin. ‘Wool’ here is the hair of the wigs men wore. In the 19th century, the status of a man was often indicated by the size of their wigs – hence the word ‘bigwig’ to indicate someones importance. Judges often wore poor-fitting wigs, low pay, which frequently slipped over the eyes, and it may have been that a clever lawyer who had tricked a judge on a point of law bragged about his deception by saying that he pulled the wool over the judge’s eyes. ‘Bigwigs’ were worth robbing too. Highwaymen and street thugs would pull the wig down over the victims eyes in order to confuse him.

Our Flounders, the original Bigwigs.

Wigs were used to cover syphilis sores, lice infections and hair loss. However, wigs became fashionable when the stylish King Louis XIV, the “Sun King” of France began to lose his hair. The image-conscious monarch began wearing long, elaborately curled wigs to maintain his appearance, turning it into a fashion trend. Wigs also conveyed social status and wealth. The style of a wig also indicated a persons profession, such as a lawyer or judge.

All kinds of words and phrases could be found in the book. The English language has roughly 170,000 words though basic communication can be achieved with less than a thousand. It’s not the wordiest of languages that would be Arabic with about 12,000,000 recorded. Arabic is far older though. English in some form dates to about 400 AD but Arabic goes back to at least 800 BCE, a difference of 12 centuries or 60 generations. More time to make up and add more words I guess.

I don’t know if dad had any particular plan for education at the table but he came from a generation that had to have books. It was reading or nothing. The first commercial radio station didn’t come along until about 1920 and his parents got their first one in 1924; he was twelve. Reading for information or facts was something he had to do. His experience led him to teach us that we shouldn’t believe half of what we read and little of what we heard. He told us to beware what we saw especially if we weren’t present at the event.

The old Almanac itself was a lesson. The term almanac is of uncertain medieval Arabic origin; in modern Arabic, al-manākh is the word for climate. The first printed almanac appeared in Europe in 1457, but almanacs have existed in some form since the beginnings of astronomy, and the study of astronomy predates any kind of written history. The earliest known almanac in the modern sense is the Almanac of Azarqueil written in 1088 by Abū Ishāq Ibrāhīm al-Zarqālī in Toledo, al-Andalus. Al-Andalus comprised most of what is now most of modern Spain. The Muslim people of northern Africa, mainly Moors, ruled Iberia for almost eight centuries.

If the idea was to create curious children it certainly worked. Presented as a game of sorts we learned to dig for answers. We could never figure out if he already knew the answers or wanted us to do the research. It didn’t really matter in the end which it was.

The one thing we all still remember that we couldn’t find in our almanac was a phrase, the old adage “Red sky at night, sailors delight; red sky in morning, sailors take warning.” Dad believed that the red sky meant good weather to come but my brother and I heard just the opposite. Why he stuck to his guns in arguing his position I don’t know but he was like a dog with a bone that you couldn’t take away. No matter how much logic or evidence we could come up with he never changed his mind. We’ve agreed that this was our best chance at winning an argument with him we ever had. The thing is he was just absolutely unsinkable.

We all added High School, a decent college education and life experience to our attempts to change his mind but he never gave in. We kind of liked that kind of stubbornness. I used to tell him I was going to put it on his headstone, but of course I didn’t.

Here lies George Gray Shannon

February 1st, 1912—–May 9th, 2000

He sailed into a typhoon because he was too stubborn for his own good.

Rest in Peace Dad….and thanks for everything

Michael Shannon a is product of Almanacs, Encyclopedias, the Thesaurus and dictionaries. He lives in Arroyo Grande California.

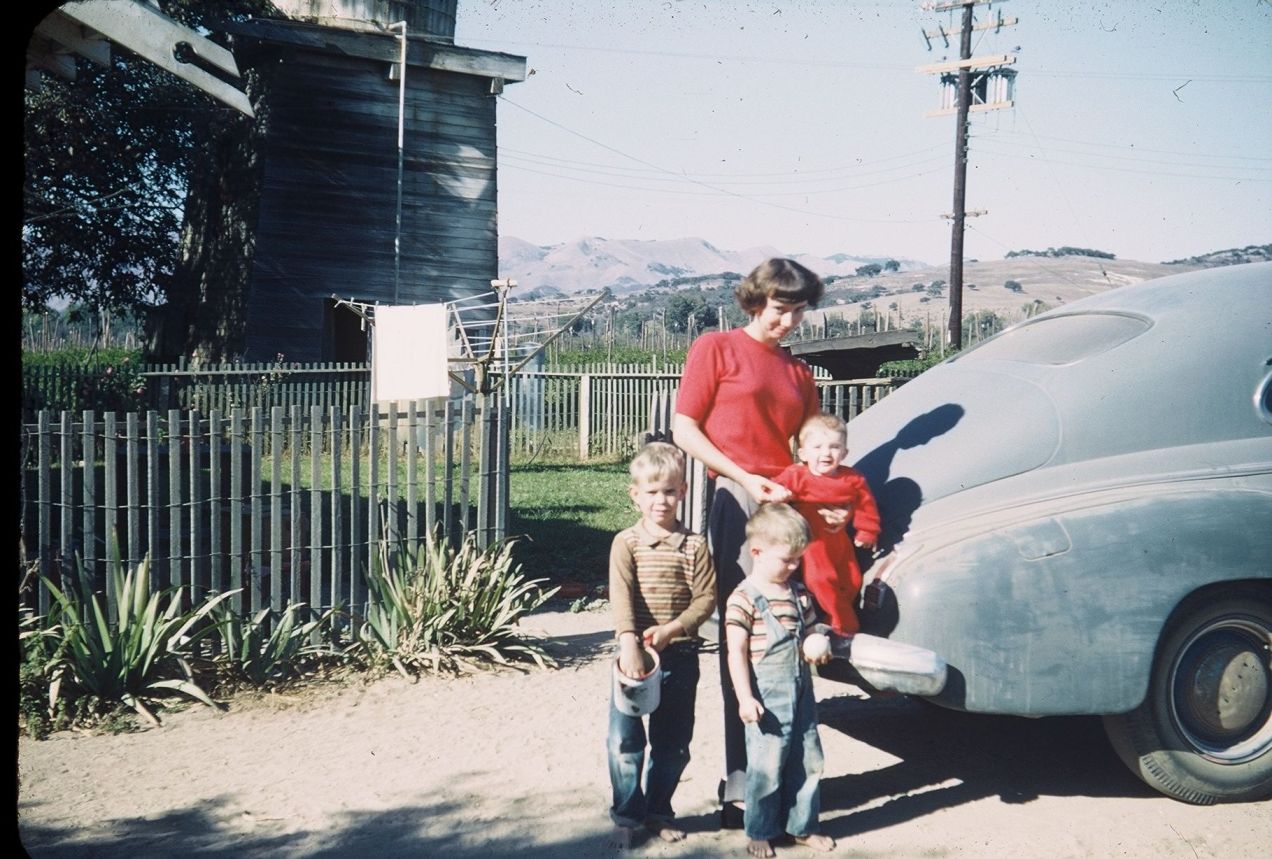

By Michael Shannon

Kids that grow up on farms and ranches are like the pups. They are always on the lookout for Dad coming out of the house and headed for the pickup truck. They know that he will lead them towards adventure. It doesn’t matter what that is, it’s just the opportunity to go somewhere with him. The dogs think the same way. The front seat of the old truck with it’s torn upholstery, and sagging springs, even the broken one which lies in wait like a rattlesnake has room for all. Over on dad’s side the viper, it’s one fang hiding just below the tattered hole where his butt slides when he’s getting out, he misses it most of the time but once he’s worn those Levis long enough they will bear the mark of the just missed.

Bumping down the farm roads, still rutted from last winter kids hold on swaying left or right depending on how many holes and ridges dad can miss.

Pride of place rules apply, the youngest sitting next to dad resting his towhead firmly against pop’s Pendelton’s sleeve, the middle brown haired one with the cowlick, squished in the middle and the oldest owning the door. He has arms long enough to reach outside and push down the chromed door handle because the inside has gone missing. My dad never focused on trivial things like hunting up an Allen wrench and digging through the cluttered tool box in the back in the remote possibility that the missing handle might be there. He used the drivers door.

Some days we drove past the tin sided pump house, the very big electric pump humming away inside pulling groundwater up and forcing it through the buried 8” pipe that ran along the uphill side of the fields. At regular intervals stubs of pipe, each one with a threaded caps stood sentinel like so many soldiers waiting for orders.

In the nineteen fifties most irrigation was fed by ditches plowed at one end of the field. Small stand pipes screwed into the risers delivered water under pressure to fill the ditch. From the ditch, siphon pipes drawing from the main ditch delivered the water to the rows along which grew the plants. Tomatoes, Celery, Lettuce, and Broccoli were all irrigated this way.

My dad with his shovel on his shoulder patrolled the dozens of rows to make sure that each one was irrigated evenly. Controlling the water by sliding the little gates on the siphons to slow or hasten the water on its way. Back and forth, back and forth like a soldier on duty. He slogged through the muddy rows building small temporary dams to slow progress, the goal being to make sure the water reached the end of the quarter mile long rows at the same time.

Simple looking to the uneducated observer the practice dates far back into the mists of time. The Hanging Gardens of Babylon were watered this way. The ancient Sumerians funneled water from the Tigris Euphrates river system to grow grain and fruit trees in the Fertile Crescent. Canals were built to bring the water down from the Zagros mountains in present day Iran to supply the cities of Mesopotamia more than twelve thousand years ago. The technology has not changed to this day. It’s simple but elegant in the way that successful technologies are. You can still see row irrigation on farms and ranches all over California. No doubt little Babylonian boys and girls played in the ditches just the way we did.

Simple but complex in the doing. The water had to be channeled in a way the provided maximum saturation of the soil for the plant to thrive. Our farm had at least four types of soil mix and each one dictated how the irrigator worked. Too dry and hot weather could kill the delicate plant before it could be irrigated again, too wet and the roots would drown and kill the plant. Water was applied differently for crops which had just been fertilized. Consider the age of the plant and it’s harvest time which the farmer knew to the day. Tractors are heavy and soft wet soil will compress and crush a plants roots. So, it’s not just a man out standing in the field, it’s a skill.

There are certain mores involved, at least for my dad. Plow a straight furrow, water highlights a crooked line and he was always checking the neighbors to see if theirs were arrow like. A small thing I suppose but it is part of what I learned from him which was how important it was to do a job well no matter its importance.

Running the water across the road onto your neighbors field was a major faux pas and dad took pride in never letting that happen. Our uphill neighbor’s irrigator, Roque ran his water onto us all the time. Dad would privately grind his teeth, muttering under his breath about lazy men but when he talked to Roque about it Roque would laugh out loud and tell my dad, “I never do anymore, Mister George” and laugh again. Next day he would do it again. My father never said much to him because he was so irrepressibly happy that it was impossible to take any serious offense. It’s difficult to fault a man that laughs.

We, on the other hand did our best to get a muddy as possible. Because we were too little to handle a shovel we used natures backhoes, our hands. The main ditch was about two feet wide and a foot or so deep, enough to drown a child I guess, but no one, us kids or my father seemed to be the least bit concerned. On the uphill side we used our hands to dig canals so we could make the water run where we wanted it. The canals went nowhere and the only purpose was to get the water to run freely. This was our first lesson in understanding hydraulics. Each little ditch had to be just off level in order to make the water move in whatever direction we wanted it to go.

Since our fields were a mix of alluvial soil and heavy adobe they made the worlds finest mud. You could add enough water to make it slurry which was really great for throwing at the pickup because it stuck like glue. A little bit dryer and it made great little adobe buildings to go alongside the ditches. Certain combinations were terrific for slicking down a brothers hair.

There were plenty of stems on the ground leftover from last seasons crops that could be woven into rafts and not far away, an old abandoned Diamond Rio flatbed truck draped with blackberry vines. The leaves could float GI Joe on his way across the Rhine River. The occasional Sycamore leaf blown up from the creek served as major people movers. Sadly many a GI Joe lost his little plastic life by being swept away on Tidal waves never to be seen again. Leaves have no handrails and though Joe can float he cannot under any circumstance swim. Pretty sure cultivators are still occasionally turning up their tiny corpses while working those fields. GI Joes may perish but their little bodies never decompose.

When we were just a little older we would hunt through the packing shed and corn crib looking for small pieces of left over wood and with a little ingenuity, a nail or two and a ball peen hammer make them into many kinds of ships and boats. Nails driven into the sides stuck out just like battleship cannon, or so the six year old mind imagined

Dozens of ships in the Japanese fleet were lost to a barrage of dirt clods fired from behind the pickup. No invasion of the Broccoli ever succeeded. As children of the second world war we understood the importance of fleet actions. Clods when lofted as high as we could toss them made very satisfying splashes. We didn’t need a game bought at the dime store we had endless resources in which to make our own games. No one I can remember ever told us the truth of things to crush our imaginations. That would come soon enough.

My little brother would crawl up the running board and lay on the front seat and nap when he got tired. Jerry and I kept it up until it was time to head back to the house. Dad’s boots and Levis would be soaked with mud and water to the knees and we could of passed for Mudmen ourselves. We had accomplished much though, held off an invasion, built hydraulic systems and thoroughly enjoyed ourselves. When you grew big enough you might get the privilege of riding the running boards back to the pump house, going inside through the tin door with its screech owl hinges and using both thumbs push the big off button on the pump.Stay a moment as the big electic pump wound its way down from its jet engine howl to silence. Little things like that mean a great deal to little kids. They understand that you earn responsibility.

Back at the house it was strip, leave the clothes on the back porch floor and run and get in the big oversize porcelain bathtub for a good scrubbing. Scrub brush on the bottom of the feet, rolled up washcloth pushed as far into the ear as mom could make it go and then a big fluffy towel, try not to slip on the wet linoleum floor, “Careful, careful,” mom cautioned over and over again. Trying to hold onto three slippery wet boys at the same time.

Funny thing I remember, Mom and Dad never scolded us for being dirty, they always seemed to be as delighted as we were.

No one ever gets over playing in the mud. Shannon Family Photo, Lake Nacimiento, CA.

“Can we do it again tomorrow, can we Daddy?”

Michael Shannon grew up on a farm in coastal California and has mastered the irrigators art himself. He has masterful shovel skills, can lay pipe and knows the secret to using baling wire to clear Earwigs from overhead Rainbird sprinkler heads.