Chapter Eleven.

Shooters and Torpedos

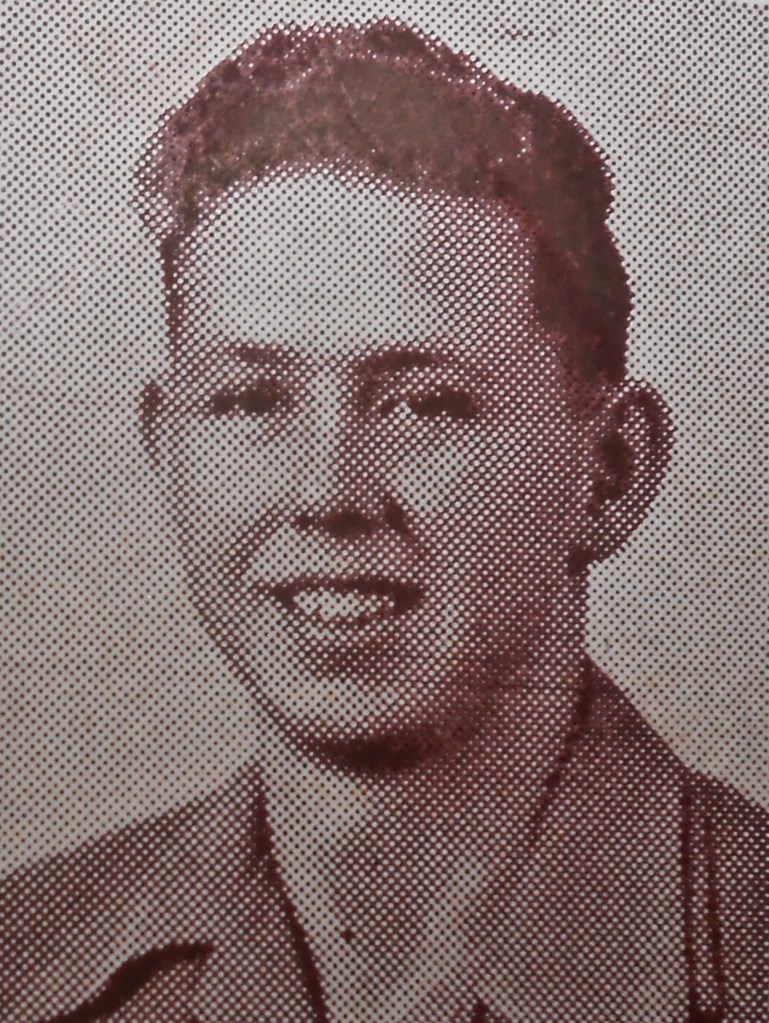

Michael Shannon.

The Shooter arrived in his Studebaker truck. His Torpedos rolling back and forth as he bounced up the road from Bakersfield. The wooden boxes which held the twenty, ten quart cans of Glycerine, all packed tightly in a wads of excelsior, held securely in place by the sideboards, strapped down. Roped in tight. His was a job that allowed no mistakes. A job for a calm and very careful man. Perhaps a man who liked to blow things up. The boy who blew up coffee cans with firecracker was a natural.

Oil isn’t easy to find. Sometimes when you find it its impossible to get to it. When Bruce’s well got down into the oil sands he knew from the debris in the bailer. Sometimes, though the presence of oil in the samples was small and the decision was made to send a torpedo down the hole and try and fracture the formation by setting of a blast and setting the oil in the mineral free. Oil flow could be increased many times over if they were successful.

Contractors that did the “Shooting” were a highly evolved trade. Sending a hollow tube packed with a couple hundreds pounds of jellied Nitroglycerine down a well took some nerve and a great deal of skill. Men who made a career of shooting were few.

In 1867 the chemist Alfred Nobel found that by taking Nitroglycerine, an extremely unstable compound and combining it with diatomaceous earth in order to make it safer and more convenient to handle, and this mixture he patented in 1867 as “dynamite”. Nobel later combined nitroglycerin with various nitrocellulose compounds, similar to, Collodion, but settled on a more efficient recipe combining another nitrate explosive, and obtained a transparent, jelly-like substance, which was a more powerful explosive than dynamite. Gelignite, or blasting Gelignite, as it was named, was patented in 1876. Gelignite was more stable, transportable and conveniently formed to fit into bored holes, like those used in oil drilling.

The Shooter, Bruce and the other rig workers knew that even after all the improvements of the previous 60 years things could still go wrong. Bruce would clear his rig of all personnel, making sure that they moved as far away as they could from the rig to be “Shot.” No one argued.

Bruce was fortunate to work for companies who took this part of rig operations seriously. You had two choices, hire experienced outfits and pay the freight or independents who were cheap but had little experience and could be hazardous to the health of everyone around them, including themselves.

If your rig was down a bad road, they would send the drivers out, tell’ em to be careful, load the soup in the back of those old trucks and send ’em off. The trucks didn’t have any shock absorbers or padding or anything to give them protection, so those guys got more money than the Toolie and earned every cent. They could be driving down an old dirt road, headed to the well and the truck would fall in a chuck hole and that would be the last of them. Every once in a while if your ear was tuned to it you could hear one take off. Nothing to do for it but to hire a new driver.

Up at the north end a Wildcat well, Arnold No 3 hit oil sands but estimated production would not reach profitable levels so the decision was made to call in a Shooter and crack the formation at the bottom of the well in order to increase flow. It was well known that Wildcatters always hung from a shoestring financially and instead of hiring out to a reputable company the looked, instead for a Cheapo outfit. They soon found one, a father and son set-up who guaranteed they could bring Arnold No 3 in. They showed up on a Sunday, hauling their dope in an old cut down Cadillac car. They packed the torpedos with two hundred pounds each of Glycerine. Now, being either too inexperienced or too stupid and lazy to do the job right they hauled all their gear up onto the drilling floor. They used the sand line to hook up the first torpedo and lifted her up ready to send her down the hole. Too lazy to pull the Key from the rotary table, figuring the torpedo would just fit they lowered her down into the Key where she just barely fit. As they lowered away, the torpedo squeaking and scraping the sides of the Key. the drilling crew seeing what was going on backed away until they were a hundred yards away for safety’s sake.

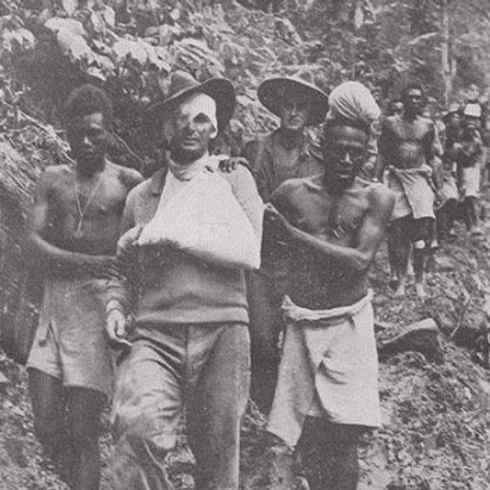

Sure as shootin’ the torpedo stuck in the key with about a foot showing and after some kicking an shoving the father took up a section of small 3/4 inch pipe and commenced to banging away, trying to get it to move. The drill rig boys saw that and turned and began to hotfoot it as fast as they could, putting some distance between themselves and the fools on the rig. The boy took another piece of pipe and started hitting the other side of the torpedo from the father, banging and banging. The slowest, youngest roughneck got behind a small pepper tree and leaned against it hoping for the best. After a minute or two the Nitroglycerin in the torpedo got tired of being abused and lit up with a roar. Father, son, rig and the Caddie vaporized. The roughneck, more than a hundred yard away was killed by the Cadillac’s door slicing right through the tree and the boys neck.

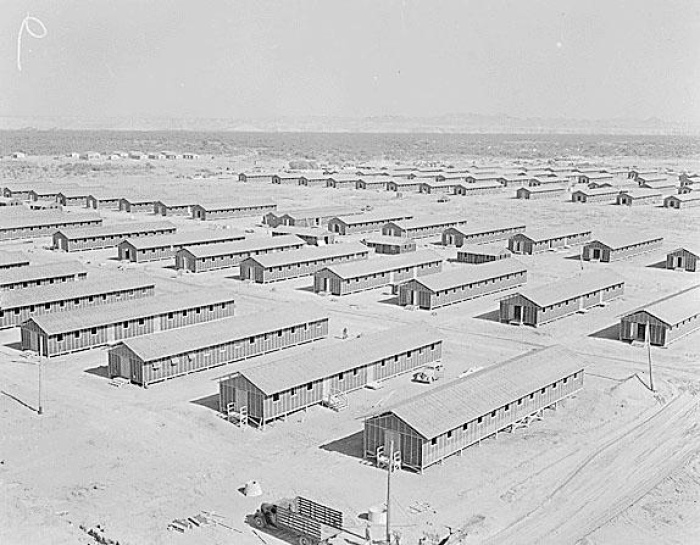

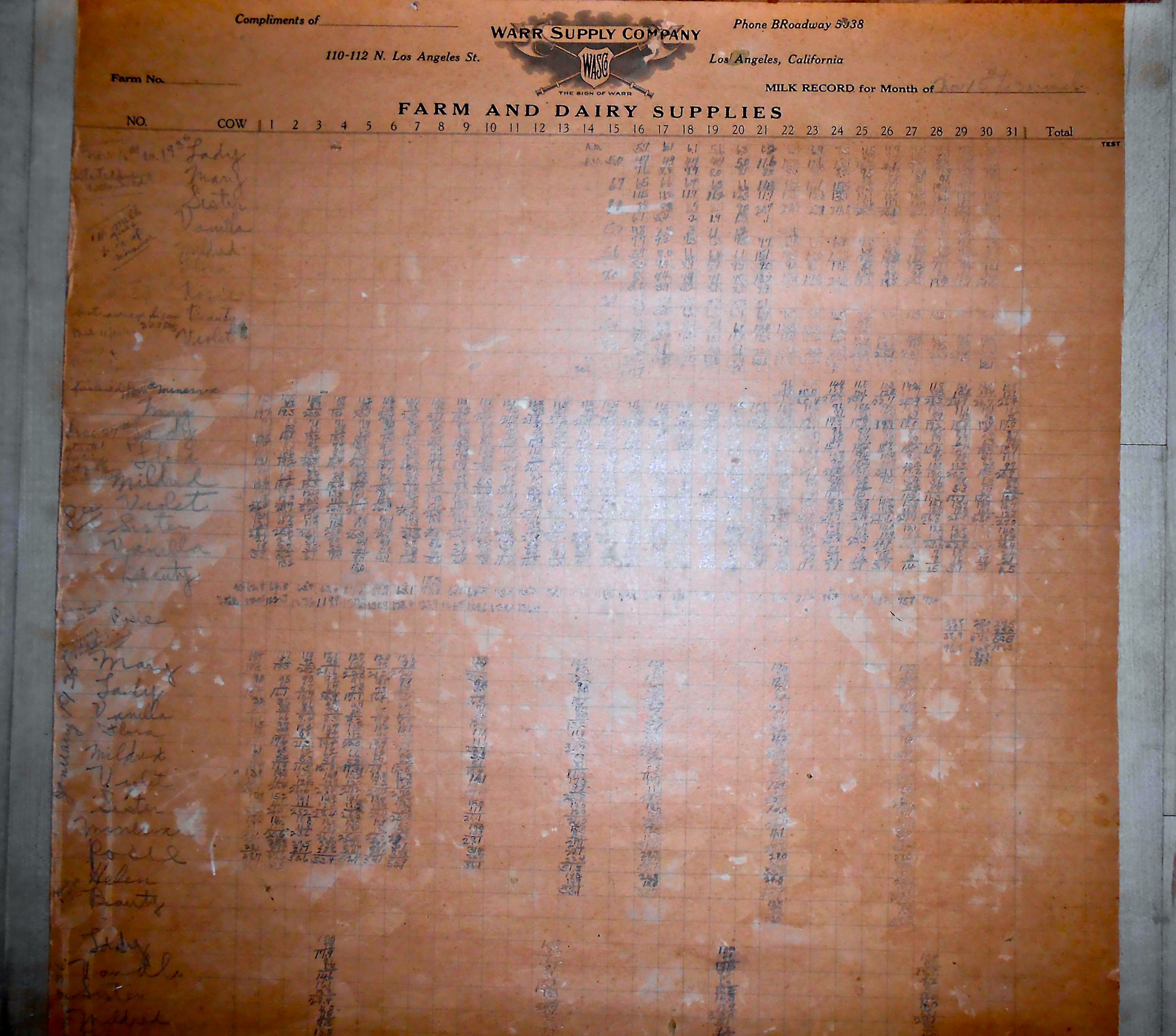

The Blast Site, Oildale, California. 1936 Note the missing passenger door.

When the dust cleared, there was nothing left of the rig or the men on it, just a huge crater nearly thirty feet deep. No part of the father and son was ever found, not a finger or foot, though they looked all around wanting to find something the poor wife and mother could bury.

The next morning, driving to work along the Valley Road, now north Chester Avenue a pusher for Standard Oil found a wheel from the Cadillac lying in the road, more than two mile from the blast site.

With a little common sense and an abundance of caution Bruce had now survived in this dangerous business for nearly a decade. The danger you can see is avoidable but the danger you can’t is not. Looming on the horizon was something that would throw the family into crisis.

The price for barrel topped $ 3.00 in nineteen and twenty and had, because of massive over production, been sliding downward. By the 1920s the automobile became the lifeblood of the petroleum industry, one of the chief customers of the steel industry, and the biggest consumer of many other industrial products. The technologies of these ancillary industries, particularly steel and petroleum, were revolutionized by its demands. With no industry organization or government oversight established corporations led by the ever hopeful wildcatters drilled and drilled and drilled.

Henry Ford’s River Rouge plant had geared up for the new Model A in fall 1927 and by 1928 was rolling them off the assembly line at 9,000 cars a day. Mass produced and marketed you could get a snazzy Ford Roadster for $385.00. Didn’t have to be black either, unlike the venerable old Model T which came, as Henry said, “In any color as long as its black. By comparison. Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford, owners of their own studio and without a doubt the best known film stars in the world really tooled around in a Duesenberg Model J which retailed for $8,700.00 dollars or about the cost of five average homes. It’s not likely they actually owned the Model A they are standing with. If they did, the cook and the maid used it to run errands.

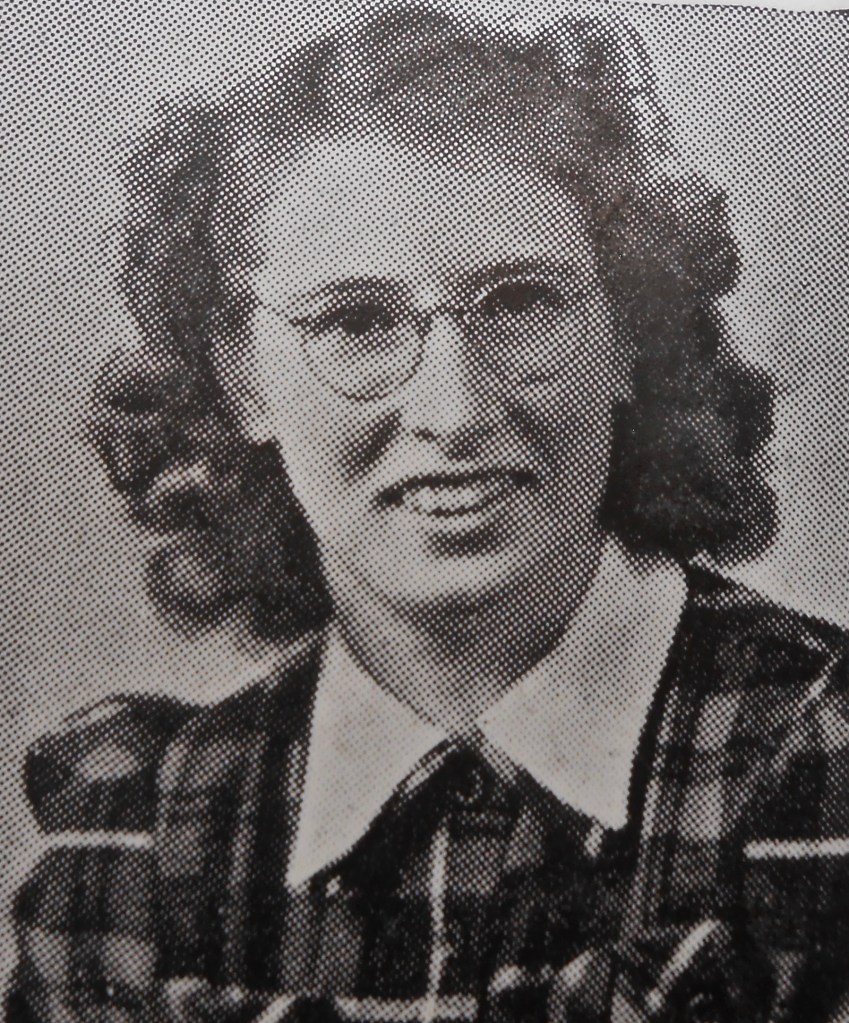

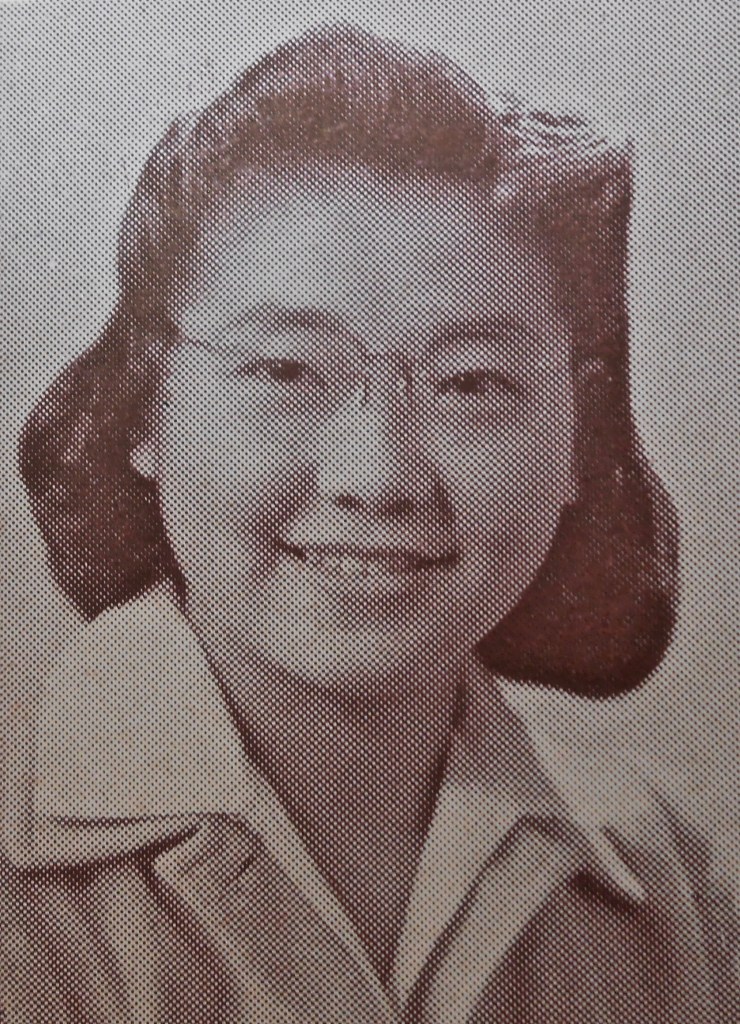

Bruce and Eileen were doing well enough. By 1928 the two girls, Barbara and Mariel were twelve and eleven about to enter high school and little brother Bob, nine. High school beckoned. They had moved from the fields in the valley where Bruce had worked for Barnsdall Oil Company wells on both the east and west side.

It was a good time to get out of the valley. Oil workers were staging strikes on the Westside in Taft, Maricopa, Coalinga. The oil companies countered by trying to bring in “Scabs” from the bay area. Southern Pacific was happy to help as they had a major stake in production. Since the end of the war when wages rose the big companies decided they would put the squeeze on their labor and had gradually driven pay down. Strikebreakers, “Scabs” were protected by armed men, paid gunsels. county sheriffs and the police who knew where their butter was. The Southern Pacific RR was happy to provide trainloads of strikebreakers to the producers. There was some nasty businewss that took place at the SP depot when these trains arrived. Bruce was always concerned about things like this and after Casmalia never lived in the housing provided by the oil companies. They rented houses away from the central retail and housing districts. Oil towns were rough as they continue to be today. Gunplay, knives, drunkenness, prostitution and the company store with it’s outrageous prices were to be avoided, especially with three young children.

Taft was a “sundowner” town, which meant that if you were black or Mexican you’d better be out of town by sundown. The Ku Klux Klan was well organized and made sure that everyone knew Taft was a White Man’s town. A Kern County Supervisor, a certain Republican named Stanley Abel even had a mountain in the Los Pinos Wilderness area nearby named after him. It still is.

The Bakersfield Californian May 6, 1922

When confronted with this revelation, Stanley Abel was unapologetic to say the least. He said in a statement the day after the Bakersfield Californian published their report: “Yes, I belong to the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, and I am proud to be associated with many of the best citizens of Taft and vicinity in the good work they are doing….I make no apology for the Klan. It needs none.”

Many in Kern county were not impressed. They started recall campaigns for Abel and others in city and county governments. Local newspaper the Bakersfield Morning Echo was staunch support of the supervisor, stating: “Those liberal Democrats promoting the recall of Stanley Abel are the enemies of good society and of the best interests of Kern County. A vote for the recall of Stanley Abel is a vote for the return of the vicious element and the vicious conditions which existed in years gone by.” Sound familiar? History allows the name to change but the song remains the same no matter the age.

The writer is the grandson of Bruce and Eileen, He and his cousins grew up with stories from the Oil Patch.