My Goodness, What to Do?

By Michael Shannon

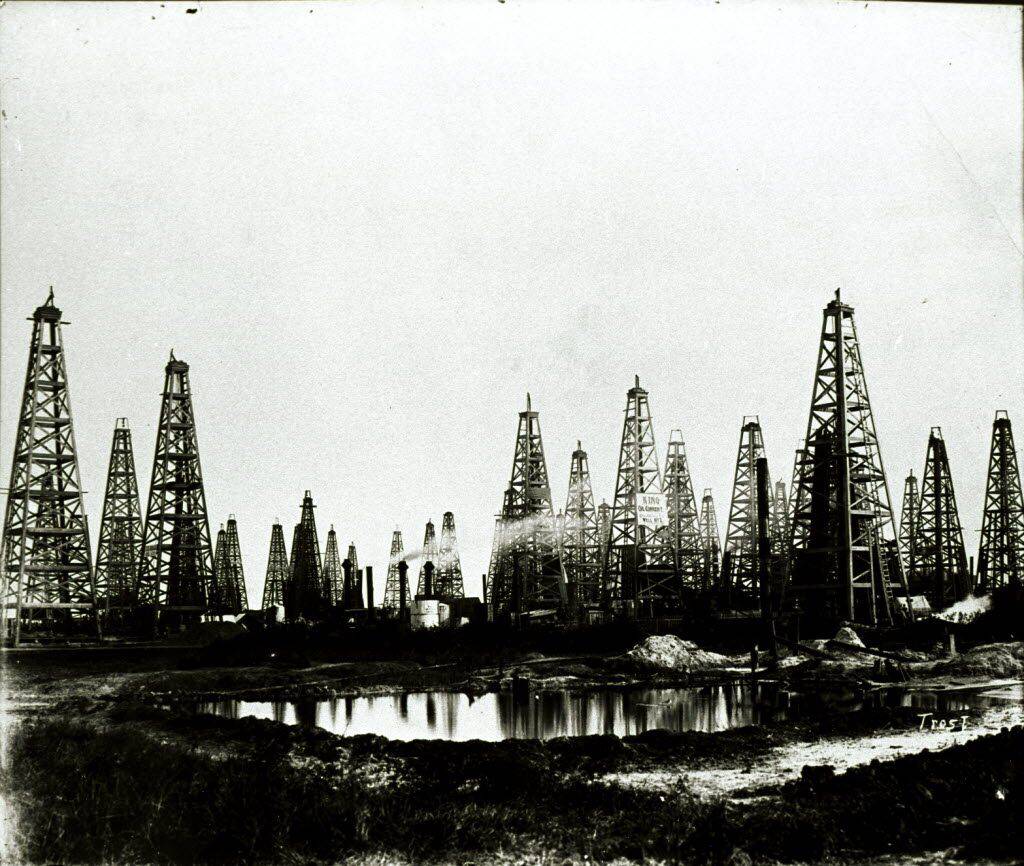

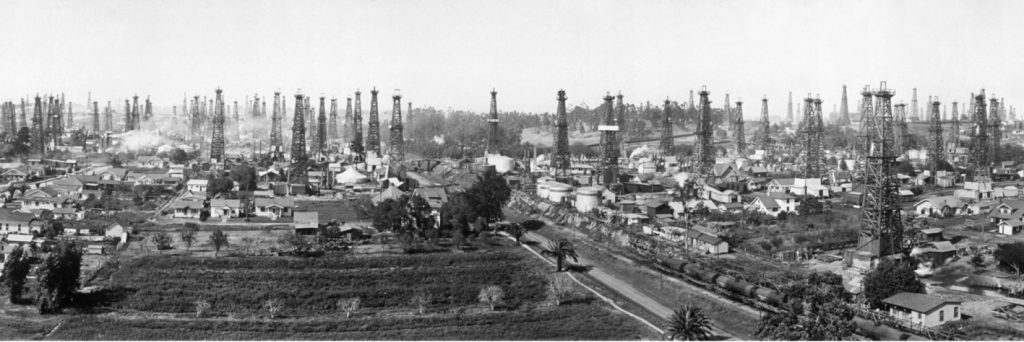

My grandmother was born in 1885. Things were different then. The little Red house she was born in down in the Oso Flaco is long gone now like most old houses built in the days before electricity and indoor plumbing. She didn’t live there too long for her father was a fortunate man and found oil on his little ranch in Graciosa, todays Orcutt. he became an instant rich man and soon built himself a large modern home on west Guadalupe road. Though rich, he was still a farmer and he worked his land which stretched all the way back to the Santa Maria River. For an landless Irishman, which most were, the land held more importance than the oil.

When my grandma Annie was eight years old she came to Arroyo Grande to live with her aunt and uncle, Sarah and Patrick Moore. Patrick Moore had come to Guadalupe from Ireland and prospered in the sheep business. Though he had little education he was a cunning man and made himself a fortune with which he built a big house on the edge of little Arroyo Grande. He bought a big book of the collected works of William Shakespeare which he kept in the foyer of his house where all could see it as they entered. That was all the education he needed.

So, my grandmother grew in a life of privilege. Servants, beautiful clothes and the best of Arroyo Grande pioneer society. Her girlhood friends were, Phoenix, Harloe, Rice, Lierly, Porters, and the descendants of Don Francisco Branch. Families that sent their children to private schools in San Francisco and San Luis Obispo.

She was a child of the late Victorian Age and all it represented. A hundred years after the first American civil war or The Revolution as it’s now styled, fashionable society still looked to the European continent for guidance in societal affairs. We will dress this way, walk this way, speak this way and adopt the mores and shibboleths that decree customs, principles, or a belief that distinguish a particular class or group of people. The majority, under the influence of vague nineteenth-century shibboleths, understood that by associating oneself with these doctrines implied sophistication to the nth degree.

I never knew my grandmother as a girl though she certainly was one. She was 60 years old when I was born. She wore sensible low heeled shoes, cats eye glasses, plain print house dresses covered by an apron with the ubiquitous hankies in the pocket. If she wore any jewelry other than her slim wedding ring I don’t recall. She wasn’t overly solicitous of my attention but she was a calm presence rocking in her chair darning socks or knitting. It was the chair my grandfather bought her when she was first pregnant with my uncle Jackie in 1908, the year she graduated from California Berkeley. She would offer her hand with its delicate skin which had hardly ever seen the sun because in the forties women still wore gloves everywhere. A little cheek was offered for a boy’s kiss which was as soft as a down feather. She always smelled of White shoulders, powder not perfume for perfume was considered vulgar and only worn by “Soiled Doves or low class strumpets.

She played the piano in church, always wore a hat to go to town no matter how mundane or routine the purpose was and was unfailingly polite, no gossip that I ever heard. If there was it was confined to her bridge club, women who had sat at those old folding tables together for nearly fifty years and likely chewed, although the word chewed which she viewed as vulgar would never have passed any of their lips, they chewed on the same old conversations until they were polished to a soft sheen. Safe, familiar and soothing.

She was raised in a quite remarkable era which is almost unbelievable today. Things we take for granted were forbidden or lived under a series of shadow words that said one thing but implied another. Society had developed euphemisms to mask words and phrase which the well-educated and socially prominent practiced.

women were as energetic as they are today but har far fewer things to occupy their minds. A contemporary woman would hardly recognize my grandmothers life in 1900. She couldn’t own property under her own name, she couldn’t vote, there were few places she could go unaccompanied. She couldn’t initiate divorce nor was she protected from domestic abuse. She couldn’t wear trousers, smoke a cigarette, she couldn’t handle money even if she had some, that was her husbands job.

She a had an Irish servant girl, her name was Clara. Clara washed ironed, served dinner and kept house for the Moore’s. She is in one photo kept in the families collection. She was apparently a scandalous girl who’s secret my grandmother kept to herself for nearly her entire life. She let it slip in her mid-nineties when her memory of the present faded and the memories of the past sharpened.

When a girl reached puberty she was likely to be 16 or 17. Poor nutrition, increased physical stress from industrial work, and other poor living conditions during the Victorian era contributed to this delayed onset. Social standing at the turn of the century figured in the timing. Children went straight to adulthood as there was no concept of adolescent until roughly 1905 when the concept was published in a book. The word teenage was completely unknown. My grandmother graduated high school in 1904 and would have been constrained to act and dress as an adult. You can see in old photographs children dressed exactly like their parents.

As a young single woman which she was until graduation from college she wore her hair up. Nearly every woman did. She put her hair up as a young teen and it stayed up until she bobbed it in 1920. Wearing the hair down as an adult woman was a scandalous thing and indicated that you were of a lower class or a, horrors to even think about it, “Lady of the night.” A fallen woman in fact and if my grandmother and her friends saw you on the street in San Luis Obispo which by the way had a rich and teeming Red-Light district, they would turn away and point there noses skyward at the scandal of it. Hmph.

The girl in the rear, Margaret “Maggie” Phoenix. Our Margaret Harloe for which the school is named. Note the ubiquitous hankies.

This developmental stage was deeply shaped by Victorian social and moral codes, which emphasized female purity and restricted young people’s autonomy. Victorian culture strongly discouraged public discussion of sexuality and puberty. This lack of frankness contributed to a cultural “prudery” surrounding these topics. Some late-Victorian medical and social commentators viewed puberty with apprehension, seeing it as a time when girls were susceptible to disease or irrationality, swooning and the “vapors” more than likely brought on by too-tight corsets. There was a push for female health and physical activity for some, but this was often met with resistance from those who preferred to preserve traditional ideals of fragile femininity. Social mores were set by the extreme upper classes in order to distance themselves from the lower or even worse, the depraved gutter Irish.

Grandma of course was just like the girls of today. They aped the manners and dress of their elders but they still found occasion for hi-jinks. Dressing up as their fathers was apparently a regular pastime. We have many photos of she and her friends posing for pictures taken with her new Kodak Brownie camera in front of her home. No lawn though as a front lawn wasn’t even a concept in 1903.

Annie Gray and Tootsie Lierley in 1903. Patrick Moore residence Arroyo Grande

You might notice that they both are both hatted. No self-respecting woman would ever be caught outside without a hat. Notice too that the skirts hem is touching the ground. It was thought that the sight of a shoe or God forbid, an ankle would drive men crazy. One of her classmates at Cal in 1907 was expelled for wearing her skirts short enough to expose he ankles. A length of fabric called a flounce was whip stitched to the hem of dresses with a small loop that could be grasped and delicately lifted just a little if she stepped over a curb or ascended the stairs. I could be removed for cleaning as often as needed since hems touched the ground and could get very dirty in a town which had no paved streets.

My grandmother is the girl in the checked dress on the left. 1907. University of California Berkeley campus.

When a woman was menstruating she was “Indisposed.” Women were such a fragile things that too much stimulation of any kind could cause her to swoon. Those darn corsets again. If a man referred to a woman’s leg as anything but a limb he might be cast out of polite society. A woman could not be touched in any fashion other than to take her arm if the road was too rough for walking. Sitting on a buggy seat, the heat from a woman’s limb was known to cause temporary blindness in men.

When she was in her nineties she still wouldn’t cross her ankles since that was considered suggestive. My grandfather didn’t cross his legs either, at least in the presence of women. You had to be careful because you were surrounded by vulgarity, it’s nasty fingers aching to clutch the unwary sophisticate.

Grandma frowned on anyone mentioning the number six, I think for obvious reasons. Animal horns were considered obscene, vulgar to the point of being devilish. Once I found a beautiful copper chaffing dish she had received as a wedding gift in 1908. That dish spent it’s entire life in the barn because the handle was a section of Elk horn which she wouldn’t touch. No goats either. My dad and uncle Jackie had to give their pet goat away, it had those devilish cloven hooves. The milk cows and bulls were also polled or dehorned, either for utility or because she wanted it that way.

She wore a silk chemise and pantaloons for underwear called, always, unmentionables. They were never seen by men. The pantaloons were basically a set of short leggings with no, dare I say, crotch. Probably shouldn’t. They wore so many layers of clothes that they simply could not undress quickly. A woman doing her business would have looked the same as a woman sitting in a chair. You see, this was because there were a couple things about feminine hygiene which were quite unknown at the time. Most homes had no toilet and many no running water. Finding and using the “Necessary” cold be very difficult when out and about. This was a woman’s dilemma. No business had a public toilet, Toilet comes from the French Toilette by the way. Toilet is French in origin and is derived from the word ‘toilette’, which translates as “dressing room”, rather than today’s meaning. This was another dodge around a seemingly vulgar term such as “The Jakes”, the outhouse, the Crapper* or the chamber pot. If I may, there was no toilet paper in a necessary unless the owner was well off . Paper for the toilet was invented by the Chinese in the fourth century BC. It took until 1857 until it first appeared in America and was sold in individual packs of five hundred and, of course quite expensive. Think of this, splinter free toilet paper first appeared in the 1930’s, multiply paper in 1942 and thanks to modern inventiveness, scented in 1964. Speaking of this would have been absolutely taboo in front of my grandmother. No lady could possibly utter the word toilet. She went to the bathroom where she did things that were secret from the world of men.

Remember that ancient Rome, Greece and Persia over three thousand or more years ago had running water, sewers and public baths and “Necessaries.” Arroyo Grande at the turn of the twentieth century did not, certainly did not.

This somewhat limited the distance a woman could go from her home. Timing was of the essence. She certainly could not just drop in to the Capitol Saloon on Branch street. She and her friends would have been forever shunned.

Saloons were places where Demon Rum lived. The men inside were considered vulgar beyond description. A woman who approached too closely would likely be subject to catcalls** and other unwanted comments.

I cannot imagine what she would think of our house when we had two rambunctious boys and one bathroom. On school days the door never closed and no one though anything about it. You all know what I mean. All that would have been incomprehensible to grandma.

As to engage in man woman stuff or Amorous Congress there was simply no word in her vocabulary that sufficed and it was never mentioned in any context, not even animals. She was a dairymen’s wife so she had to make her peace with sort of thing. She was seriously uncomfortable with both words and I’ve heard the act itself was only practiced twice, resulting in two children. Or so my father said, tongue in cheek, I hope.

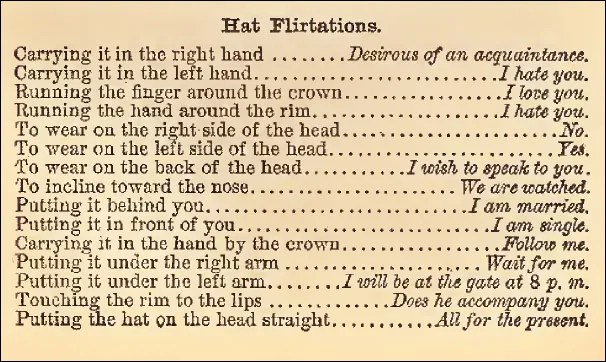

Girls and boys didn’t have to wonder what the rules of courtship were, you could buy a printed card.

So my grandmother, her name was Annie Shannon was a steady presence in my life growing up. She never raised her voice, she always dressed the same, she never ever went out without hat and gloves even if she was going to buy groceries. She taught her grandchildren not to masticate with their mouths open, keep our elbows off the table, not to speak unless spoken too and keep our opinions to ourselves. I’ve done poorly with the latter but I hope she will forgive me.

I loved her for who she was and I miss her.

Jack and Annie Shannon as I remember them. Arroyo Grande about 1950.

Cover Photo: Annie Gray formal portrait high school graduation 1904. Stoneheart Studios Santa Maria California.

*Thomas Crapper was an English plumber and businessman. He founded Thomas Crapper & Co in London, a plumbing equipment company. In 1861, Crapper patented his first invention – an improved ballcock mechanism. The device was used to regulate the flow of water in cisterns and is still used today in toilets across the world. I cannot not imagine my grandmothers reaction to the word ballcock, it may have killed heron the spot. Crapper’s notability with regard to toilets has often been overstated, mostly due to the publication in 1969 of a tongue-in-cheek biography by New Zealand satirist Wallace Reyburn.

**Catcalling is a form of street harassment, typically sexual in nature, where a man makes unwanted comments, gestures, or sounds toward a woman in public. It is not a compliment but a demeaning act that makes the target feel threatened, degraded, and unsafe. The motivations behind it can include asserting power, misogyny, or a desire to express sexual interest, but it is always a form of harassment that infringes on the target’s dignity and right to feel secure in public.

Michael Shannon, the author of this piece loved his grandmother. Both of them actually because they were characters in their own right.