Page 7

A Long Way From Arroyo Grande

Written By: Michael Shannon

When your dad was transferred up to Port Moresby with his team he was introduced to a place he never imagined while he grew up in Arroyo Grande.

He certainly read Tarzan of the apes when he was a kid and must have imagined the African jungle as it was described by Edgar Rice Burroughs. In the time honored way of writers, Burroughs himself never ventured any closer to Africa than Chicago. As kids, the places we know outside our own existence are described in a way that rarely has much relation to the real place where the story takes place. No less your fathers generation whose visual images wee formed by Life magazine or the jungle movies he saw at the Mission or Pismo theaters. It’s not much different today. Moviemakers are rarely too concerned with an actual location when they are creating a mythical place.

I’ve been to Papua New Guinea. I can testify as to its holding the title of one of the greatest hell holes on earth. When Hilo arrived in Port Moresby with MacArthurs headquarters the port itself was a tiny backwater of the colonial British empire. Papua New Guinea had a population of approximately 3,000 people, 2,000 natives and about 800 Europeans.

Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, 1943

Port Moresby was a small British administrative center at the time, with only two track dirt roads connecting nearby coastal villages. The city was dry for eight months out of the year, from June to January, and locals had to depend on rainfall or transport water from other areas. For a place considered one of the wettest place on earth and because it was in the rain shadow of the Owen Stanley range it received only fifty inches of rain annually. It seems like a great deal if you grow up in Arroyo Grande where the average is about 19 but your dad would soon find out what real tropical rain is all about.

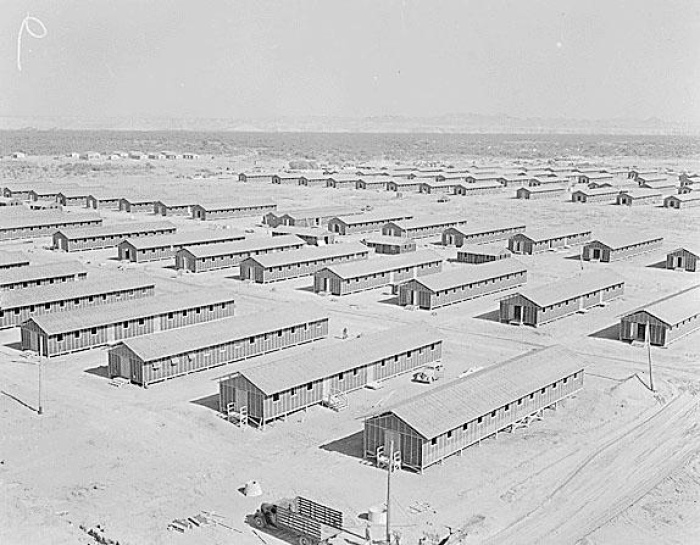

Imagine the introduction of nearly 18 thousand allied troops into the area. The general and some of his staff took over the British administrative buildings but almost everyone else lived in tents. There is no real way to experience the climate unless you go there. New Guinea is just about four hundred miles south of the equator and in the western regions the annual rainfall exceeds 125 inches a year. Think of that in feet. It’s raining there today and tomorrow and the next day and so on and so on. Plus its more 90 degrees and the humidity is roughly the same. Don’t worry though, it will cool off at night to about 85 or a little more. When the sun is out it can cook your skin in just a few minutes.

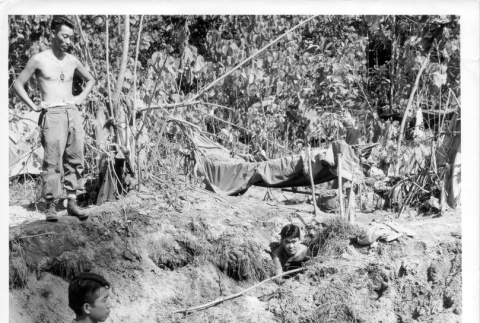

Port Moresby tent camp, 1943.

Flora and fauna? New Guinea has one of the most diverse ecologies on earth. It is home to every kind of biting, stinging and poisonous insect, even the wild dogs are dangerous. Think about birds, the Hooded Pitohui is extremely poisonous, and isn’t the only one. Some cockroaches can grow to six and seven inches long. There are nasty scorpions, stinging hornets, bees, caterpillars and moths, moths of all things. You want some relief? Go for a swim where in the ocean which is home to the deadly stonefish, killer sharks, Poisonous stingrays, remember the Crocodile Hunter? And snakes, sea snakes, very deadly and my personal favorite the “Two Step Snake,” if he bites you, you get two steps and you die.

The biggest killer in human history thrives in tropical climates and was responsible for more deaths in the Pacific than even the most horrific combat, especially for the Japanese Imperial army which was notoriously casual about the well being of it’s troops. Statistically somewhere around 95% of Japanese combat soldiers died of disease or starvation during the campaigns in Papua New Guinea.

Sidewall Tent Living, Port Moresby.

If all of that was not enough, living in a sidewall tent, sleeping on folding cots under mosquito netting you could also fall victim to Dengue fever commonly referred to as Breakbone Fever for which there was no vaccine until 1997. Add to this list Yellow Fever which killed tens of thousands during the building of the Panama Canal, Chagas, a parasite you get through the bite of the apply named “Assassin Bug.” Add Cholera which is transmitted through contaminated water and all kinds of parasites such as Hookworm, Roundworm, Whipworm and Tapeworm.

For Americans, disease was responsible for about 10% of deaths in the Pacific war but in the casualty column it was by far the biggest cause of loss. At any given time about 4% of US troops in the Pacific were unavailable for duty.

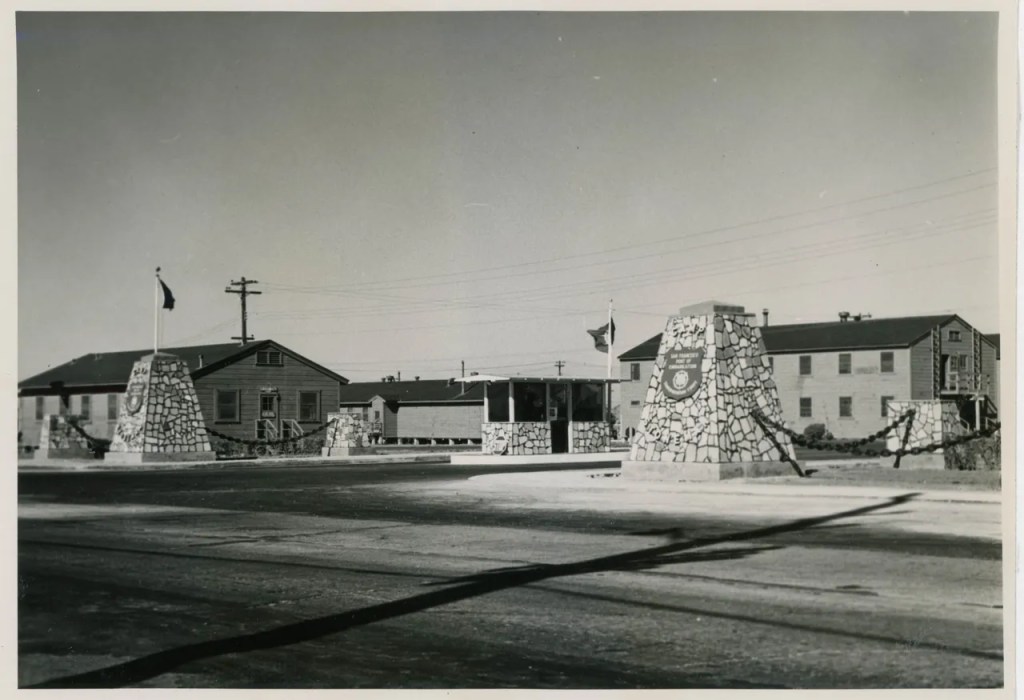

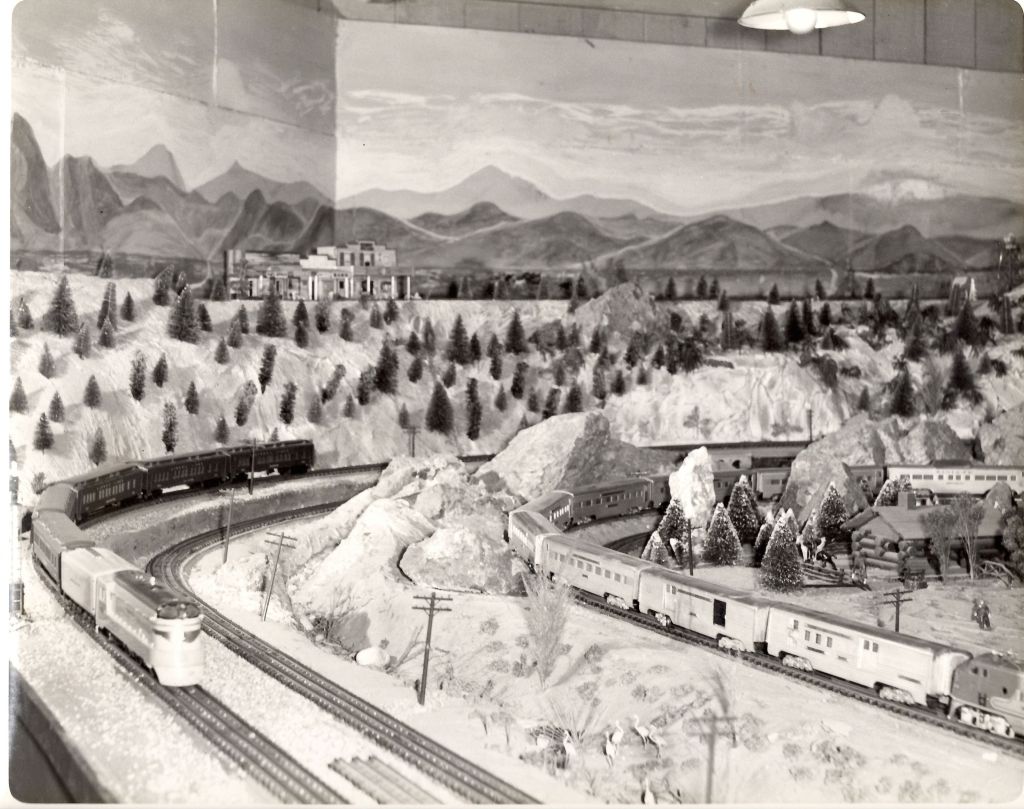

The MIS boys were ordered up by MacArthur in early 1943. He had around sixty who were loaded with their gear aboard the Australian navy’s transport HMAS Kanimba and sailed to Ferguson Harbor at Port Moresby. When they arrived there was almost no accommodations for them. Troops were billeted in camps scraped out of the brush. It would be months before Navy Seabees arrived and began building an airfield and erecting the ubiquitous Quonset huts so familiar to anyone who has ever lived in the Pacific islands.

Army service soldiers from the 93rd Division (Colored) worked around the clock unloading supply ships and building shelters, kitchens and other necessary support structures including showers and laundries.

His Majesty’s Australian Ship Kanimba unloading at Port Moresby, 1943. Australian War Museum photo.

In one of the funny things regarding race, which was an ongoing issue, the white officers and troops had only cold water showers but the Black troops built themselves hot water showers. Your father said the Nisei showered with the African Americans. Apparently the white troops never figured this little act of defiance out. A small rebellion but a taste of a future army*

At Port Moresby, your father and the others on his ten man team moved into their tents and quickly began digging slit trenches. The Japanese sent bombers on a regular run down from Rabual to pound New Guinea. The sound of bombs rattling down from high above sent soldiers diving head first into their fox holes and trenches. When your dad first arrived the ground troops had not pushed the Japanese army far enough to stop the harassment. It would be their first experience of the shooting war but not the last.

As a farm boy Hilo certainly knew about digging. Nikkei Archive photo.

The workload of the translators was very heavy. Because combat in New Guinea was unceasing as the allied troops slowly pushed the Japanese Northwest and out of the island, documents, letters and personal journals stripped from the vast number of dead** Japanese troops which by this time the allies understood to be of significant importance.

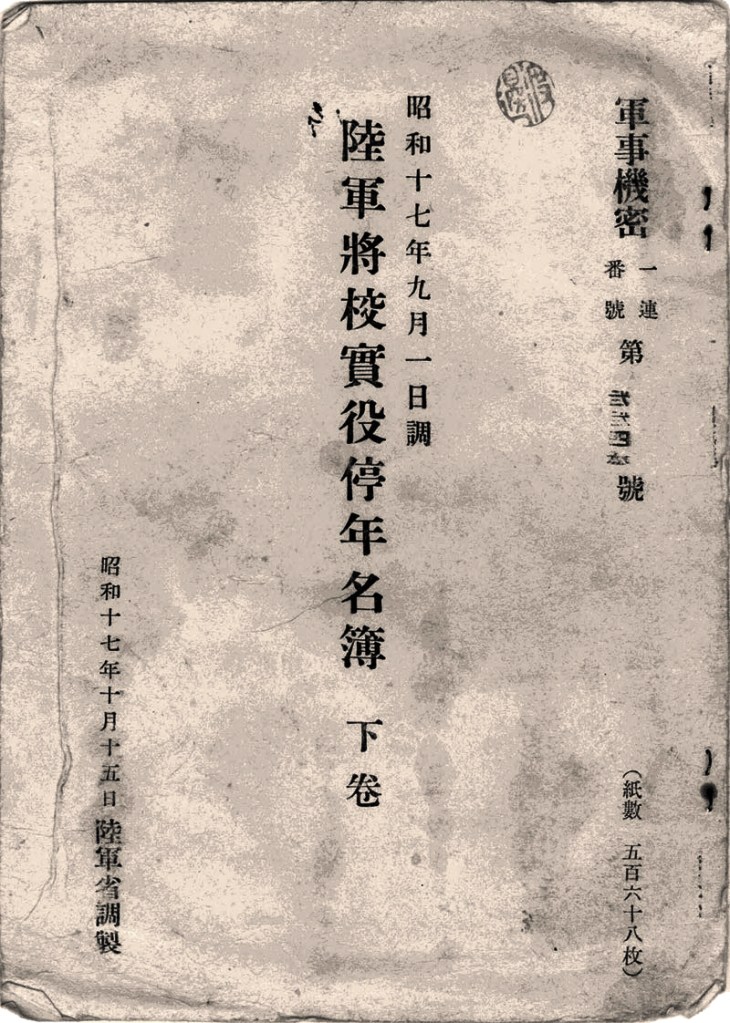

A Detail from the Japanese Imperial Navy’s Warship and Officer list. National Archives.

The battle of Midway in 1942 was partially won because of the MIS. Radio intercepts by the translators along with the breaking of the Japanese Naval code by the code breakers at Pearl set the stage for the ambush of the Japanese carrier force headed to Midway island in the northwest Hawaiian island chain and a good bit of sheer luck blunted the Japanese carrier navy which would never fully recover. It was the first nail in the coffin of Imperial Japans plans for the Greater Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

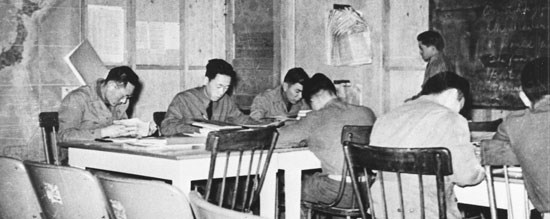

American commanders initially resisted using MIS nisei for their intended purpose, the gathering of information about the enemy. Thanks, however, to the persistence of a haole plantation doctor from Maui, Major James Burden, and the work of the nisei themselves, attitudes changed quickly. Major Burden took an MIS team to the South Pacific. They had to work hard for a chance to prove themselves. Nisei with the 23rd “Americal” Division in New Caledonia worked around the clock to translate a captured list of call signs and code names of all Imperial the Japanese Navy ships and air bases.

Major Burden and the nisei pushed to get closer to the action, and some wound up on Guadalcanal, where they made a big discovery: the joint operational plan for Japanese forces in the South Pacific.

Found floating in the Ocean it was brought ashore by New Caledonian natives and turned over to an Australian Coast watcher who arranged to get it to the 23rd’s headquarters. The Mis translators quickly discerned it’s contents and forwarded the documents to Army, Navy and Marine senior officers in Hawaii and Maryland. The hubris of the Japanese high command in not changing codes or plans meant that US forces in the Western Pacific were able to use the information to follow troop movements, fleet assignments for the rest of the war. Just this one thing validated the wisdom and the expense of the Army in forming the MIS teams.

There was more to come.

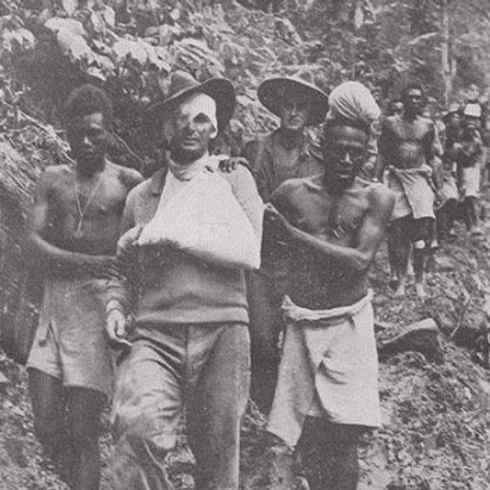

Above: SIMINI, New Guinea, January 2, 1943: From left, Major Hawkins, Phil Ishio and Arthur Ushiro Castle of the 32nd Infantry Division question a prisoner taken in the Buna campaign. Information from POW interrogations produced vital tactical information countless times. National Archives photo.

Next: Dear Dona, page 8. Moving up towards Japan. Maurutai, Luzon, Leyte, and Okinawa.

*Presiden Truman integrated the armed forces. On July 26, 1948, President Harry Truman signed Executive Order 9981, creating the President’s Committee on Equality of Treatment and Opportunity in the Armed Forces.

**The 23rd Infantry Division, more commonly known as the Americal Division, was formed in May, 1942 on the island of New Caledonia. In the immediate emergency following Pearl Harbor, the United States had hurriedly sent three individual regiments to defend New Caledonia against a feared Japanese attack. They were the 132nd Infantry Regiment, formerly part of the 33rd Infantry Division of the Illinois National Guard, the 164th Infantry Regiment from North Dakota, and the 182nd Infantry Regiment from Massachusetts. This division was formed as one of only two un-numbered divisions to serve in the Army during World War II. After World War II the Americal Division was officially re-designated as the 23rd Infantry Division, however, it is rarely referred to as such. The division’s name comes from a contraction of “American, New Caledonian Division”. The Americal Division was involved in ground combat in both World War II and Vietnam.

***From the Owen Stanley Mountains in New Guinea to Luzon, Philippines, the 32nd Division walked that long, winding and deadly combat road for 654 days of intense combat, more than any other American unit in World War 2. The Red Arrow was credited with many “firsts”. It was the first United States division to deploy as an entire unit overseas, initially to Papua New Guinea. The first of seven U.S. Army and U.S. Marine units to engage in offensive ground combat operations in 1942. The division was still fighting holdouts in New Guinea abd the Phillipines after the official Japanese surrender.

****The 93rd (Colored) was a combat trained division led by white officers. The “Blue Helmets” as they were known were almost never used in combat but reduced to labor battalions. The Division had shown in WWI in France that they were a fearsome outfit but in this war they were rarely given the chance and were reduced to no more than “Hired Hands.”

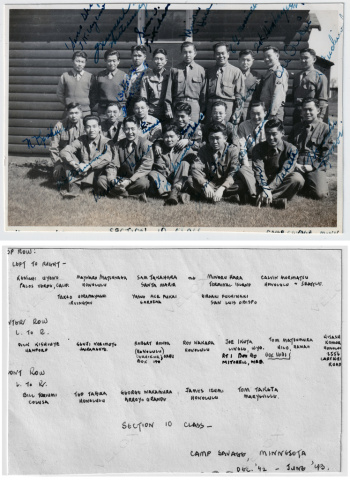

Cover Photo: General Frank Merrill posing with Japanese-American members of the Marauders. Fourteen Japanese-American service members with the Military Intelligence Service served as translators and codebreakers (Image courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration)

Michael Shannon is a lifelong resident of California. He writes so his children will know where they come from.