Page 12

Closing the Ring

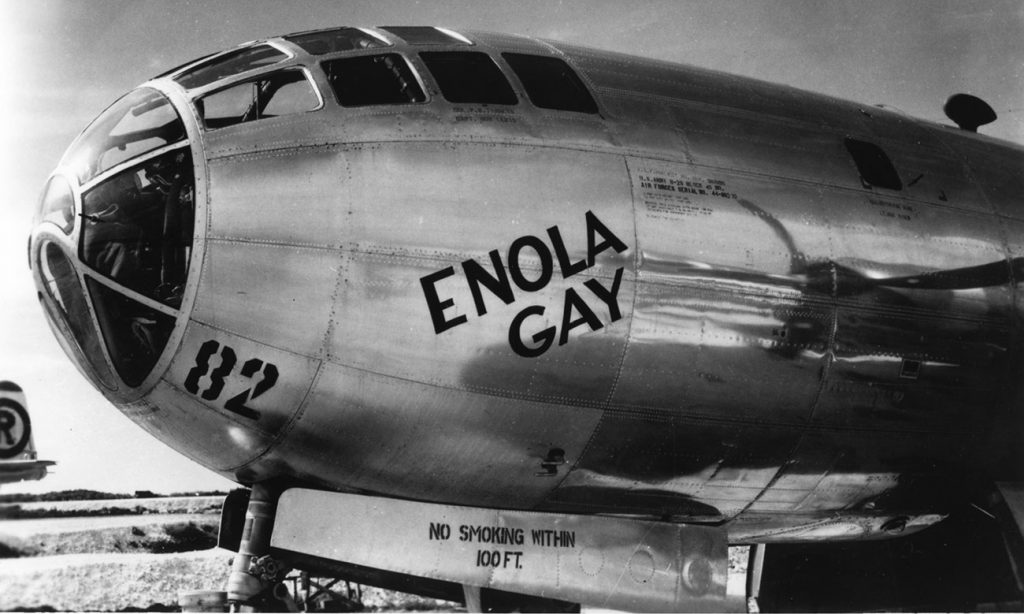

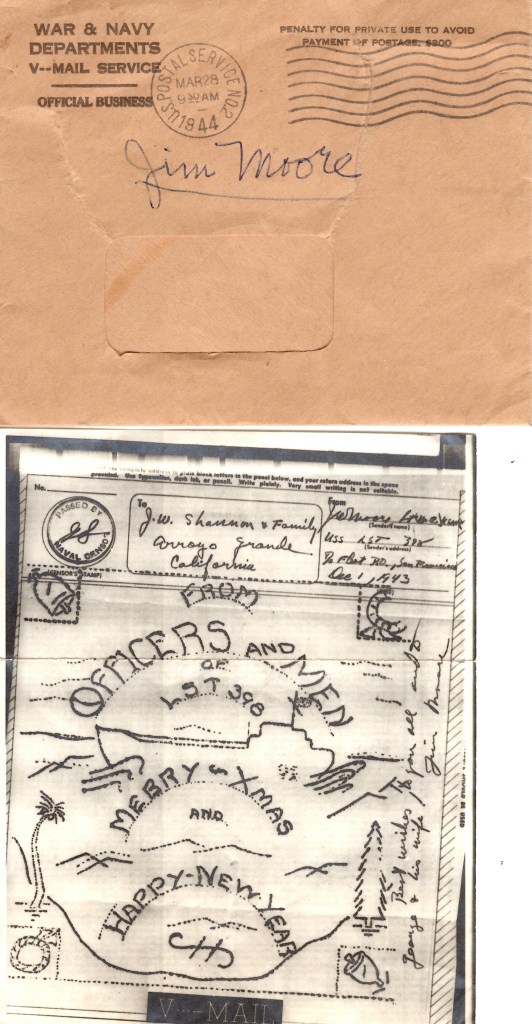

Landing Ship Tank was the official designation for the ship your dad traveled on to Luzon. The Navy thought that the name was adequate, they didn’t believe they deserved an official name such as those given to “Real” fighting ships. Sailors of course, being very young and with a patented sense of irreverence simply called them Large Slow Targets. Nearly forty were lost during the war so the swabs were right on the mark.

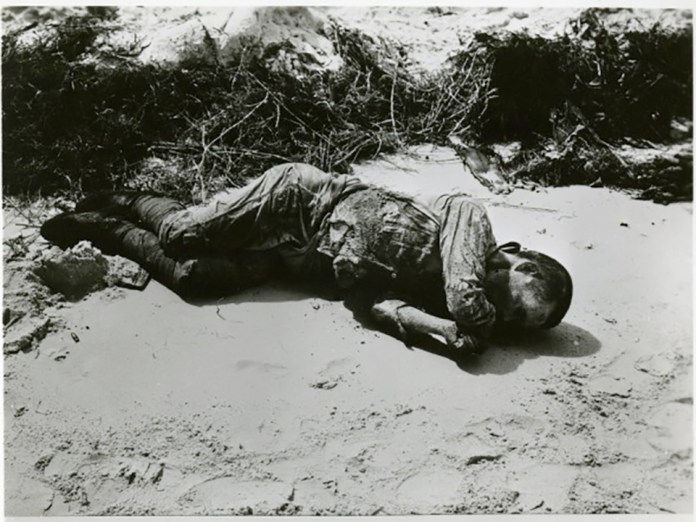

Disembarking from a large slow target, Lingayen Gulf Phillipines. US Navy Photo.

MacArthurs army charged down highway 55 towards the City of Manila. General Sasaki had chosen to leave only a few units along the 224 miles of the fertile Cagayan valley that runs down the center of Luzon. They convoys of American troops sped past Tarlac City, Angeles, San Fernando to Valenzuela on the outskirts of Manila proper. Though the allies had declared Manila an open city and had planned to bypass it. The Japanese were determined to defend it.

In the run down the valley, Some of the major guerrilla groups materialized out of the Corderillas and joined the regular tropps of the Eleventh and sixth corps. Groups led by Ramon Mafsaysay, future president of the Phillipine Republic, Russell Volckmann who was a West Point Graduate and had escaped into the mountains in December 1941 and led a guerrilla force of over 22,000 men*. Robert Lapham was a reserve Lieutenant in the 45th Regiment, Philippine Scouts and escaped into the jungle just before the fall of Bataan in 1942. Considered the most disciplined and successful of the guerrilla groups he moved into the Zimbales mountains where his 13,000 fighters fought with General Walter Kruegers sixth army.**

MacArthur ordered your dad’s team to Zimbales province where they were to be stationed in Olongapo City on Subic Bay. Subic was to be one of the prime the anchorages for the Navy as the Allies prepared for the invasion of Japan. By early 1945 the Navy operated over 6.700 ships of all types and Harbors like Subic and Manila Bay were essential to provisioning and maintenance.

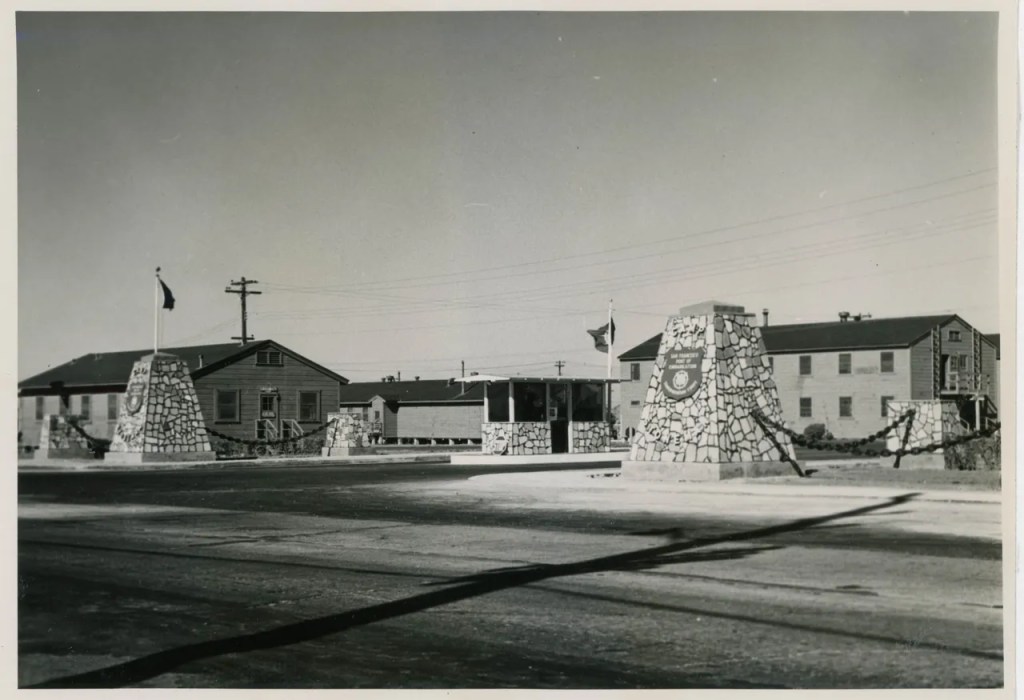

Arriving at a large permanent base the team would have had the opportunity for the first time since landing on Luzon to strip off their filthy uniforms, shave and be relatively safe. For the first time in a long while the chances of being killed or wounded by artillery, Japanese bombers or snipers was behind them. For perhaps the first time your dad could stand up straight without fear of being killed. One MIS soldier said that when he moved into the Quonset hut he was to live in he was reminded that the slamming of the screen doors caused him to stand there and repeatedly open and close it because it reminded him of home so. He said it made him literally weak in the knees.

Hilo must have looked out at the country they were traveling and been reminded of his home in California. The land was gentle and planted in crops tended by families who lived on it. The feral and disturbingly inhospitable jungle, the Green Hell he and his friends had lived in for two years was replaced by a land more familiar to the farm boy from Arroyo Grande.

The island was such that a war of maneuver, where overwhelming numbers of troops and war machinery such as tanks an aircraft gave the allies a great advantage. American industry helped to turn the tide. I read of a German soldier captured in France asking his captors. “Where are your horses?” The Germans moved by horse drawn vehicles and had never dreamed of the American ability to produce. The Japanese Imperial army was equally amazed.

Highway South to Manila. War Department 1945.

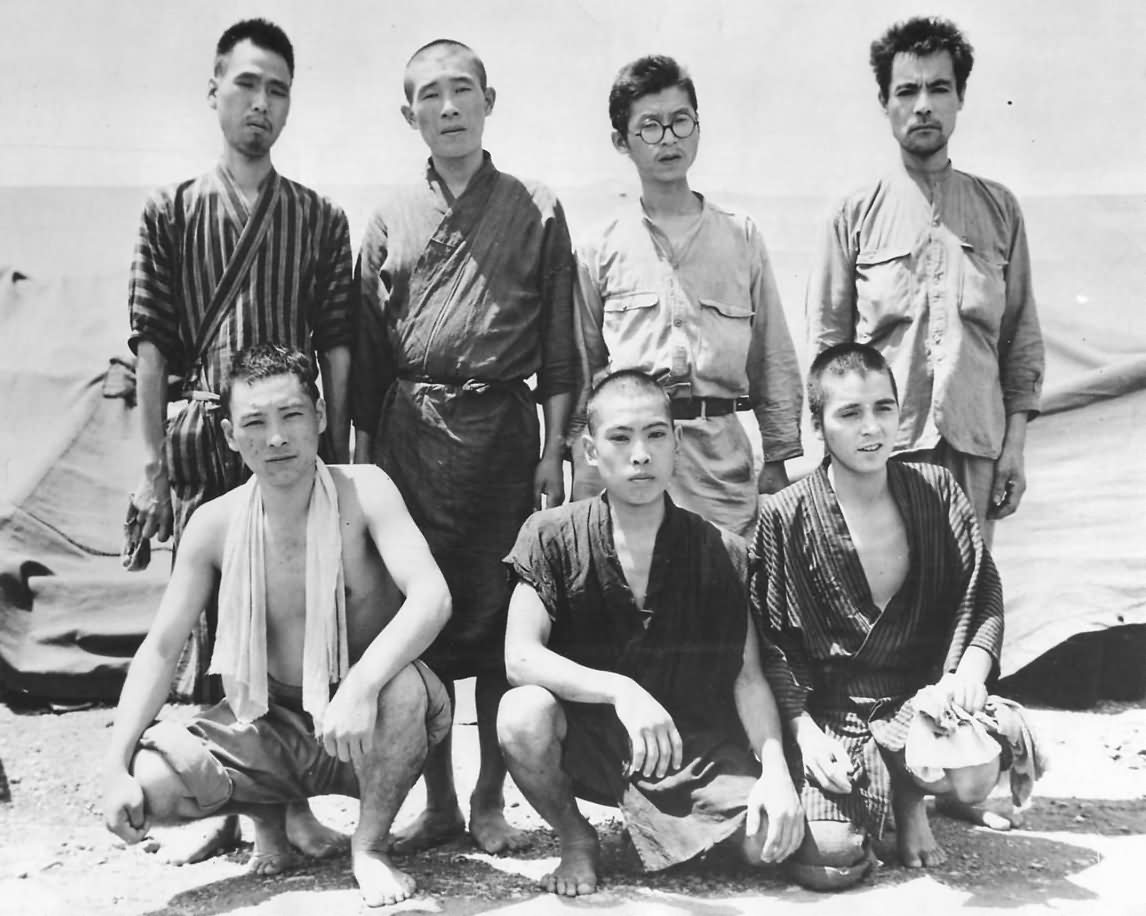

The job of the MIS was to put together as much information as they could for the planners of the coming invasion of Japan proper. Captured documents, radio intercepts, military orders, maps and personal letters were to be collated in order to locate as precisely as possible every installation, road, railroad, landing strip In the islands. They even knew the home addresses of individual officers and enlisted men. It was a monumental task.

No longer suspect, Military Intelligence had long proved its worth. The battle of Midway, Guadalcanal, the island hoping campaign, MacArthurs drive up the southwest Pacific, The ambush of Admiral Yamamoto, Merrills Marauders, The mission in China supporting the armies of American General Stillwell and Chiang Kai-Chek, The battleship encounter in the Surigao Straits of the Phillipines along with the organization of the vast amounts of information obtained through all sources gave the allies an impressive view of the Japanes forces everywhere.

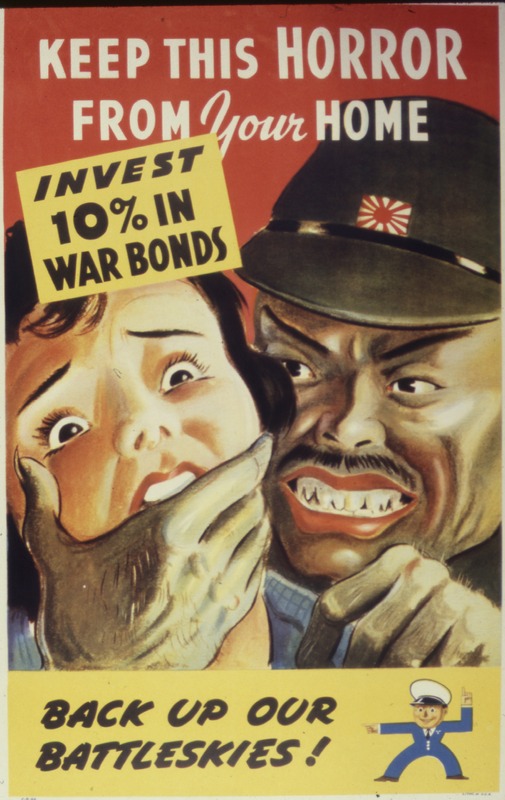

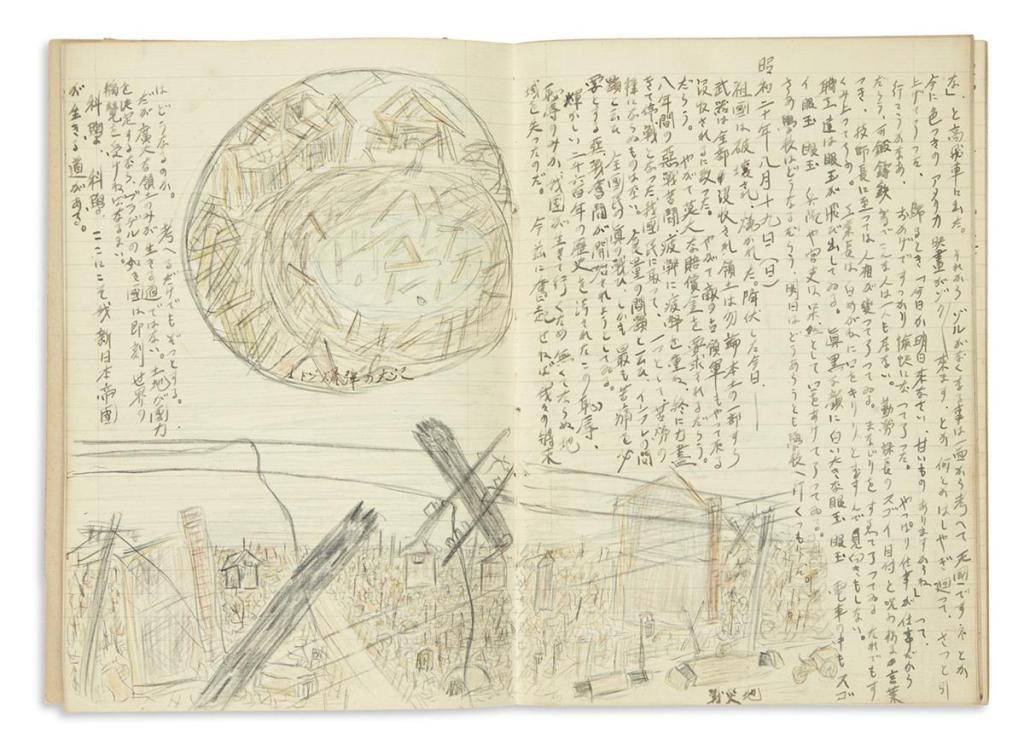

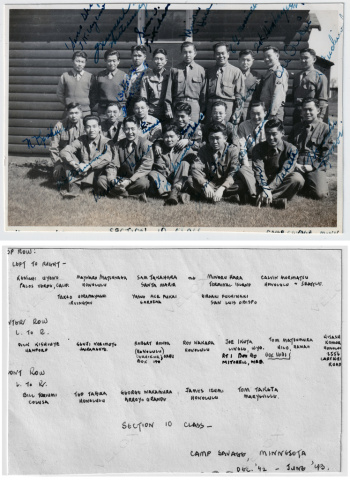

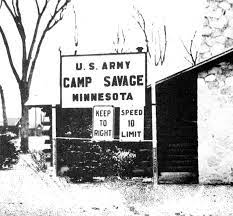

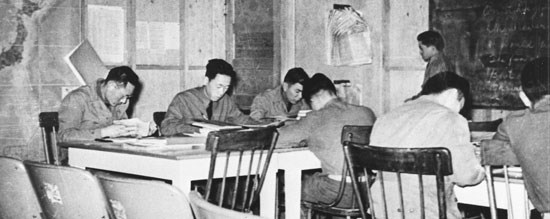

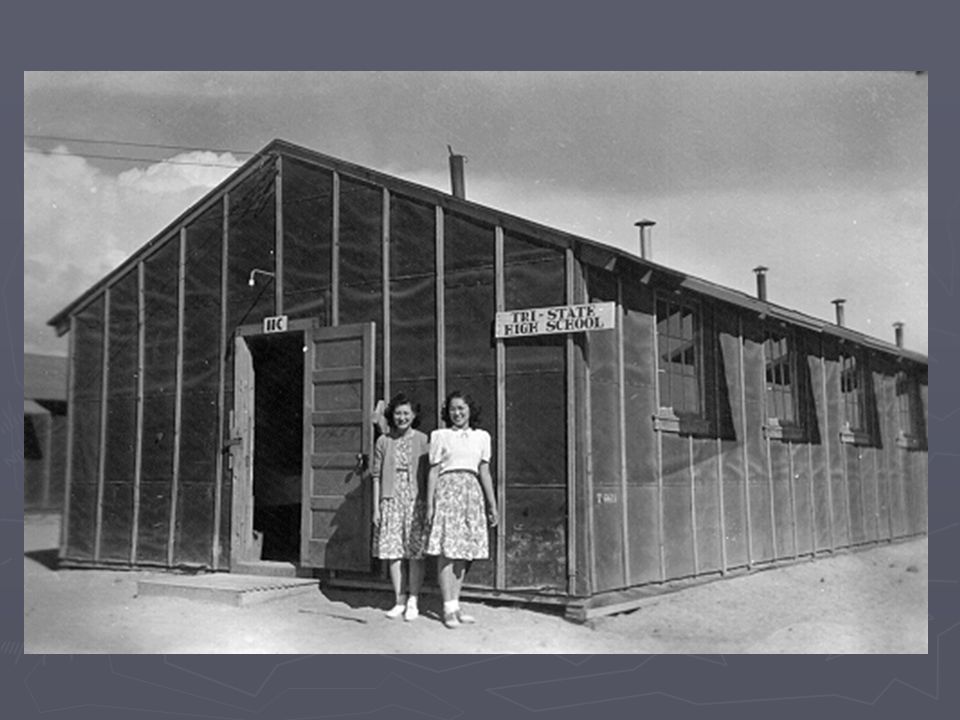

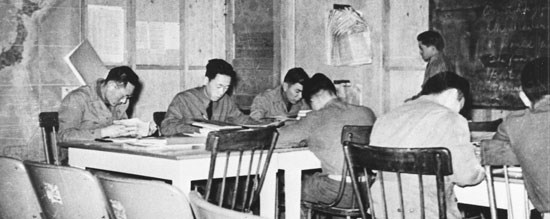

Housed in Quonset huts, hundreds of MIS translators worked around the clock preparing the information that would be need for what was planned as the largest invasion in history. The planning assumed multiple invasion beaches scattered around the Japanese homeland. In the coming invasion of Japan, the US navy planners favored the blockade and bombardment of Japan to instigate its collapse. General Douglas MacArthur and the army urged an early assault on Kyushu followed by an invasion of the main island of Honshu. Admiral Chester Nimitz agreed with MacArthur. The ensuing Operation Downfall envisaged two main assaults – Operation Olympic on Kyushu, planned for early November 1945 and Operation Coronet, the invasion of Honshu in March 1946. The casualty rate on Okinawa was to be 35% of all troops and with 767,000 men scheduled to participate in taking Kyushu, it was estimated that there would be 268,000 casualties. The Japanese High Command instigated a massive defensive plan, Ketsu Go (Operation Decisive) beginning with Kyushu that would eventually amount to almost 3 million men with the aim of breaking American morale with ferocious resistance. All men of any age, women and children were to be drilled for the effort. Thousands were issued sharpened stakes for use. The plan was for a resistance that would cause the ultimate collapse of the empire and the end of the Japanese nation. Resistance would be suicidal. Some estimates of American casualties ran as high as a million killed and wounded.

It’s impossible today to imagine what the military leaders and planners struggled with. Ordinary soldiers who were involved in the planning must have simply been sick at the thought. No one knew about the bomb. He wasn’t told about it until after President Roosevelt died on April 12th, 1945. From President Truman on down the inevitability of the holocaust in Japan for all countries must have been horrific. America was already exhausted. Too many dead boys to bear. Casualties in other allied countries were much higher than ours. In Great Britian there were literally nl boys left. Generals waited impatiently for 17 and 18 year old boys to graduate and be eligible for conscription. As in WWI these children were referred to as “The class of 1917” or “The class of 1944.” Back home in Arroyo Grande, class of 44′ boys included Gordon Bennett, John Loomis, Tommy Baxter and Don Gullickson who would all be in the Pacific by wars end. It must have seemed a universe of war with no ending. Most soldiers and sailors never made it home for a visit. From 1941 you father had spent over fourteen hundred days without seeing his family. There must have many nights lying on his cot in the steaming tropics unable to sleep thinking about his family, not knowing precisely where they were, how they were being treated; would he ever see them again. There was no answer to be had.

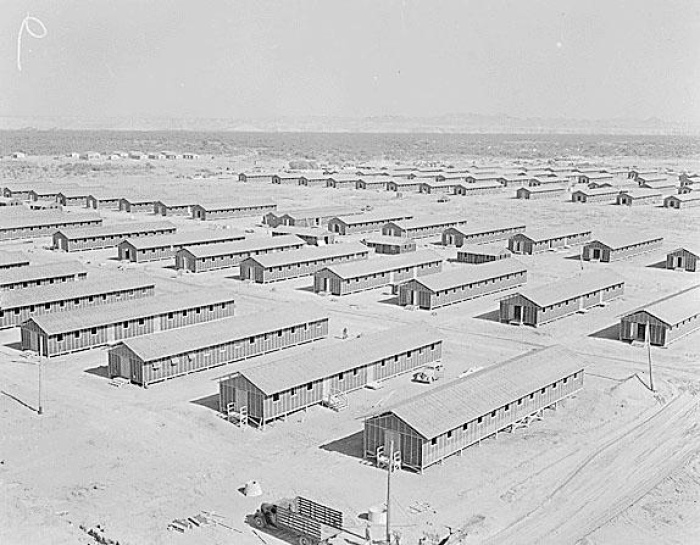

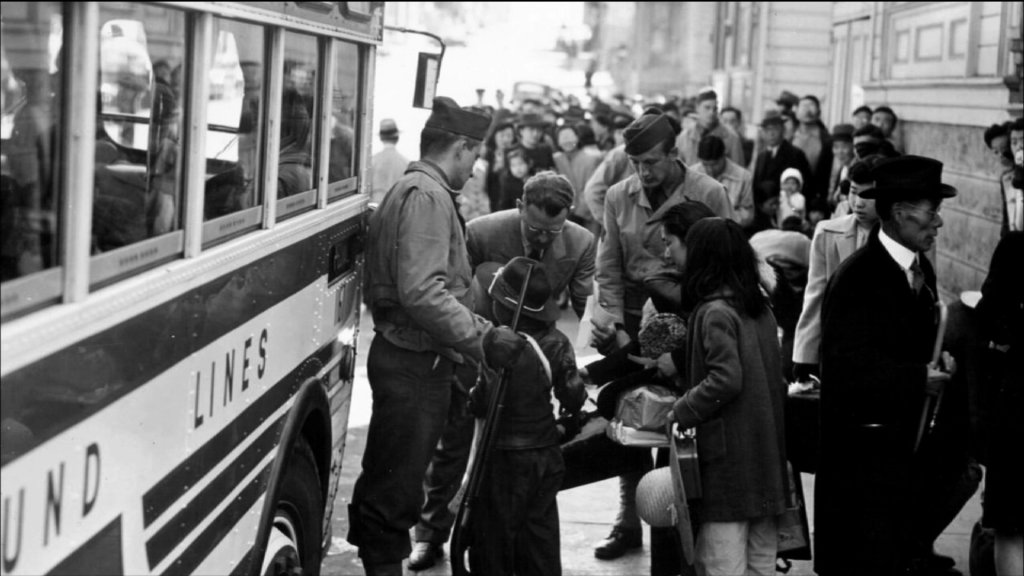

Exhaustion would have been written on the face of your father by the beginning of 1945. He had been overseas for over three long years. He hadn’t seen his family, surrounded by barbed wire and guard towers with machine guns pointed inward for going on five years. Corralled in the Southwest Arizona desert, winter and summer it must have been agony for Hirokini and Ito. Until 1943 theirs could not visit them. The fact that the boys had volunteered to serve the only country they knew meant little to military administrators.

The agony of mothers is compounded by the fact that though grandparents knew he was somewhere in the Pacific they never knew exactly where or what he was doing. Headlines in the Newspaper blared massive headlines praising the military for the carnage they caused and were exposed to. Casualty figures, though not typically released to the press didn’t stop the reporters on the wartime beat from happily publishing the butchers bill.

There is a scene in Saving Private Ryan where, in the distance a small farmhouse and barn somewhere in the wheat-fields of mid-America you see an automobile being driven along a dirt road. It’s a drab green color with a white star on its door. It’s rolling through a cloud of dust of its own making. A middle aged woman in the kitchen goes about her business, rinsing the lunch dishes, her hair styled in the rolls worn by mothers and grandmothers of the time. As she moves about dressed in a red print housedress and an apron exactly like your grandmother wore, she begins rinsing the dishes in the sink. A little movement in the distance catches her eye and she looks up to see the car as it turns up the road to the house. The woman, who you know immediately is the mother of the four Ryan boys because there is a small banner hung, almost without notice by the camera, on the kitchen wall. Framed in red with four blue stars on a white background indicating four children, boys, just boys in the service. Mrs Ryan looks up, sees the car, goes back to the dishes, with her head still down it registers. Why the car is here. She looks up again and grows absolutely still, She knows. The heart goes still, scarcely breathing, she sleepwalks to the screen door and stands, her slippered feet spread, very still as the car pulls up. She does not move. Everything in the scene is in suspended animation and when the doors open, first an officer in uniform from the front then her pastor from the back door, she loses control of her legs, staggers and then slowly, agonizingly collapses on the floor boards. It goes to the heart of every mother who sent a son off to war. It’s the finest scene Spielberg has ever made.

Mrs Margaret Ryan at the window, sees the car, in that instant she knows. Note the white picket fence reflected on the glass in a way that suggests white crosses. Superb imagery. Spielberg is a master artist. Screen capture. Amblin Entertainment, Mutual Film Company. 1998

The battle for Manila was to be the most destructive operation in the war outside of Stalingrad and the final apocalypse of Berlin. In the movie, “The Pianist”* the final scene is Adrian Brodie standing in the ruins of Warsaw, Poland. Though it’s a movie set, the scale of destruction is enormous, it borders on insanity, hopelessness and utter destruction. Such was Manila.

Your father had a ringside seat working at Subic Bay. MacArthur himself had a personal attachment to the city, he had lived there for many years. His son had been born in a Manila hospital and when he was serving in the Filipino Constabulary he was often quoted that it was his favorite city. An ancient city with wide avenues and scores of beautiful old buildings shaded by tens of thousands of trees, the dignified Narra with its gorgeous yellow flowers underlayed by the fallen blossoms carpeting the walks below, the unfurling Dapdap known as the Coral Tree with it’s diamond shaped, fiery red blossom, and the huge and ominous Balete, trees renowned for their expansive, sprawling roots and branches which are said to be home for sorcerers.

Gracing the ancient streets deep in the city, “Old Manila” refers to the historic walled city of Intramuros. Manila was known for its Spanish colonial architecture and historical landmarks like Fort Santiago and the San Agustin Church. Fort Santiago (Saint James, the patron Saint of Spain) was built between 1590 and 1593 by the first governor of the Spanish Phillipines and anchored the city center.

Your dad never saw it. By the time he left the Phillipines it was a graveyard of buildings, people and culture.

When the Japanese attacked the islands in 1941 MacArthur declared Manila an open city and withdrew his troops to save it from destruction. This was not to be the case in 1945 when your father was there. General Tomoyuki Yamashita, he commander of the army withdrew his forces from the city into the mountains of the northeast portion of the island leaving Yamashita decided not to declare Manila an open city as MacArthur had done but that Gen. Shizuo Yokoyama, destroy all bridges and other vital installations in the area and then evacuate his men from the city as soon as American troops arrived in force.

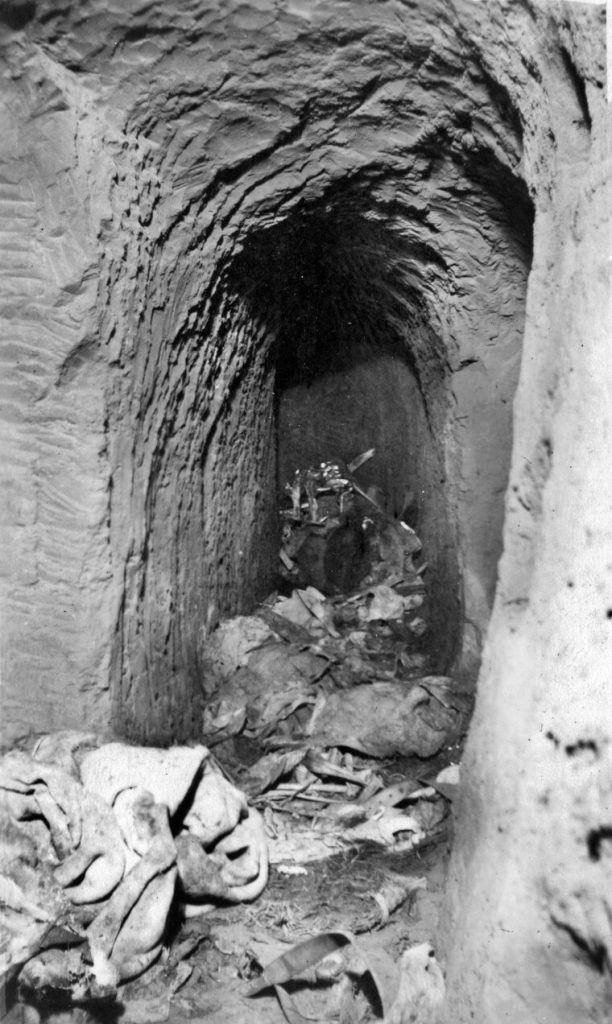

In spite of these orders, Rear Admiral Sanji Iwabuchi, commander of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s 31st Naval Special Base Force, was determined to fight a last-ditch battle in Manila. Iwabuchi repeatedly ignored orders to withdraw from the city. From the beginning of February 1945 until march, some of the most vicious street fighting of the war took place. Artillery and air strikes reduced the beautiful old city to a vast landscape of roofless shells. The Japanese forces resorted to a suicidal defense, refusing to surrender and murdering tens of thousands of Filipinos, men, women and children. Accounts from US soldiers tell of rape and systematic execution of the civilian populace. For the remainder of March 1945, American forces and Filipino guerrillas mopped up Japanese resistance throughout the city. With Intramuros secured on 4 March, Manila was officially liberated, although the city was almost completely destroyed and large areas had been demolished by American artillery fire. American forces suffered 1,010 dead and 5,565 wounded during the battle. At least 100,000 Filipino civilians had been killed, both deliberately by the Japanese in the various massacres, and from artillery and aerial bombardment by U.S. and Japanese forces. 16,665 Japanese military dead were counted within the Intramuros alone.

Afterwards, City of Manila, April 1945. War Department photo.

From Subic Bay where your father was, the sound of fighting would have heard. Flashes on the horizon coming from fires and exploding bombs would have illuminated the night sky. He heard the rolling thunder of the defenders being crushed. No one really knows the number of Japanese troops and civilian Filipinos died there. At the end the Imperial Army simply executed any Filipino they could find. They burned them with flame throwers, lined them up against walls and move them down like wheat stalks, they locked them in churches and burned them alive. Women were brutally raped and then shot. It was Hell on earth. It simply cannot be imagined except by those who lived through it and those, especially the soldiers, sailors and nurses to save their sanity simply locked it away. PTSD as it is known today is not a recent phenomenon but has been known by all veterans since Thermopylae and the Phalanx’s of Alexander and the Emperor Xerxes.

Dear Dona

Chapter 13

Coming Next

The Final Blow.

Cover Photo: The Fort Santiago Gate after the battle for Manila. War Dept. Photo.

*Brigadier Russell W. Volckmann was one of the founders of the Army’s Special Forces units after the war. His experience as a partisan commander was highly valuable in the formation of that elite force

**In 1947, Lapham returned to the Philippines for five months as a consultant to the U.S. on the subject of compensation to Filipinos who had served as guerrillas during the war. He recognized 79 squadrons of guerrillas under his command with a total of 809 officers and 13,382 men. His command suffered 813 recognized casualties. However, sorting out the deserving from the fraudulent was difficult. Of more than a million claims for compensation in all the Philippines, only 260,000 were approved. Lapham believed that most of his men were treated fairly, but was critical of U.S. policy toward the Philippines after the war. “If ever there was an ally of American whom we ought to have treated with generosity after the war, it was the Philippines.” He said the U.S. Congress was “niggardly” with the Philippines, providing less money for rebuilding than that spent in many other countries, putting conditions on Philippine independence that favored U.S. business and military interests, and backing corrupt Filipino politicians who protected American, rather than Filipino, interests.

***The nurse, LT. Sandy Davys from the film “They Were Expendable” by John Ford surrendered with the other 86 nurses on Bataan and spent the war years in the Los Banos and Santo Tomas internment camp in Manila. They all survived.

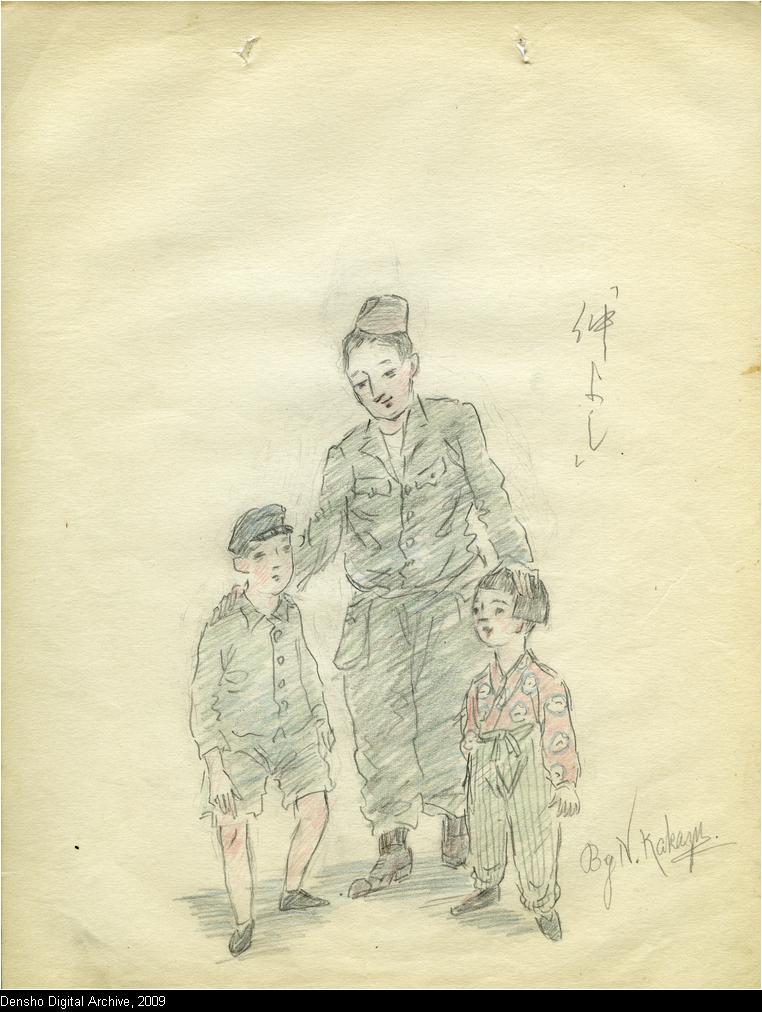

“The Angels of Bataan” War Department Photo. 1945

****”The Pianist,” the Oscar-winning film, is based on the real-life story of Władysław Szpilman, a Polish Jewish pianist who survived the Holocaust. Szpilman’s memoir, also titled “The Pianist,” details his extraordinary survival in Warsaw during World WarII.