Chapter 21: At School

Michael Shannon

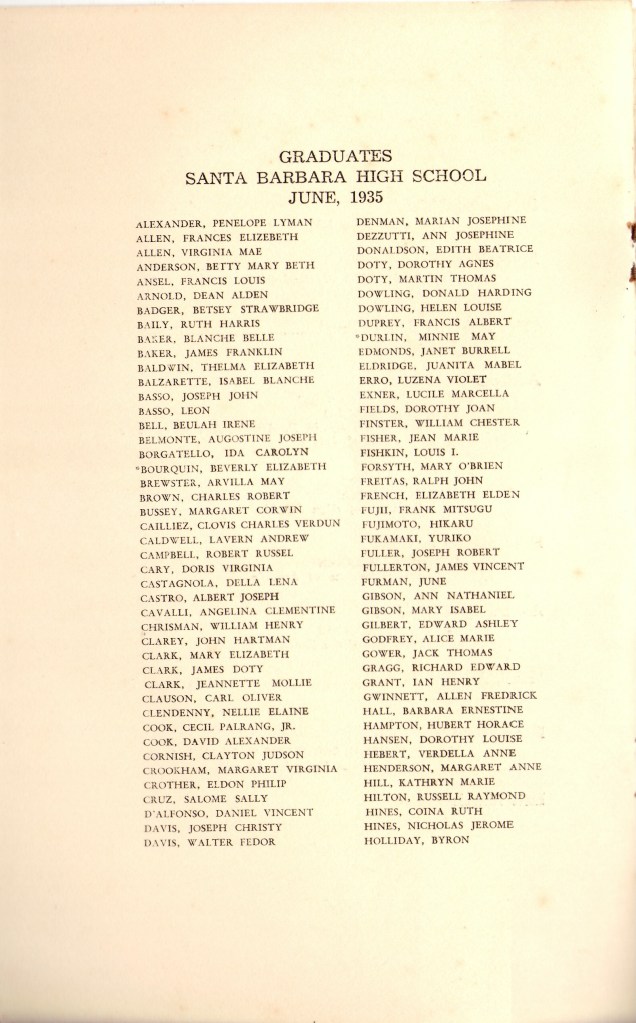

On the flyleaf of the 1936 Olive and Gold Santa Barbara High School yearbook is written in fine cursive, “Barb, Best wishes to my best friend and good luck in the future, as always your friend Blanche.”

With this inscription my mother closed her school career on a high note. There could have been no finer school in California.

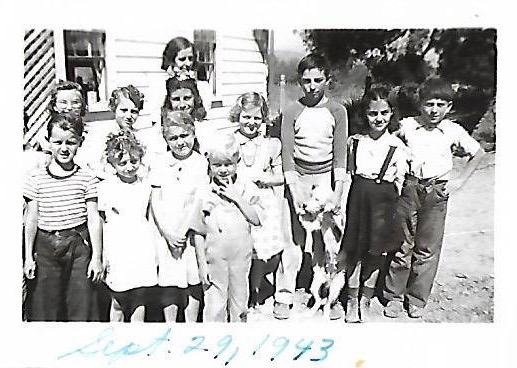

She was there for two school years, the first time in her twelve years of school that she had spent an entire year in a single school. The list of schools she attended is too long to list but if you drew lines between places it would look like a cobweb. From Kernville, Oildale to Taft, Maricopa and Orcutt/Santa Maria, or Wilmington/Artesia and Long Beach/Compton up to Goleta and Santa Barbara a meandering school journey driven by the random rush to find oil.

I used to think that that was such a sad experience. I soon learned that the kids developed a strategy to deal with it and that was to seek out the popular kids and make friends with them right away. Bruce and Eillen made a point of always living outside the shanty towns where laborers lived or the Silk Stocking Rows where the big bosses lived.

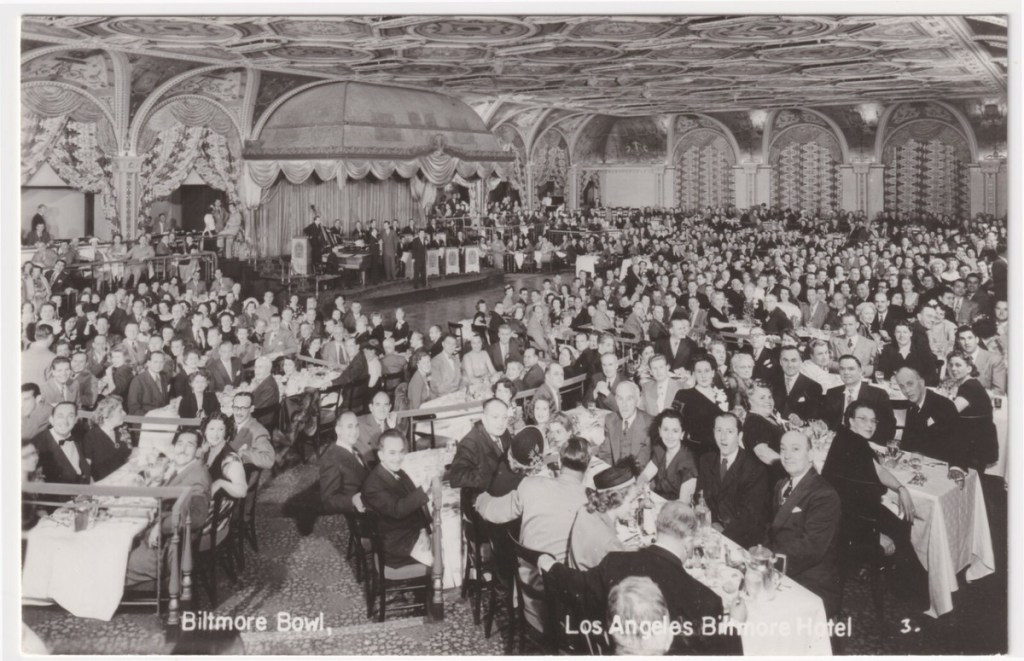

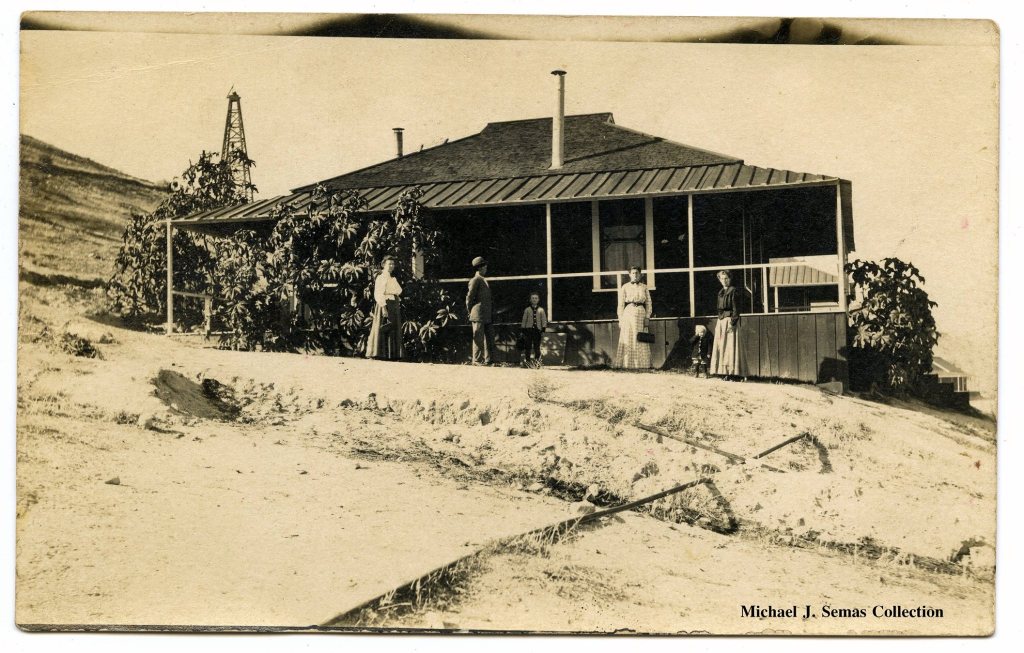

Oil camp, Kernville, ca and Silk Stocking Row McKittrick Ca. Used by permission.

If they could live in what would now be a middle class area, they did. No one would be able to call their kids Oil Field Trash nor be considered of the Snooty sort either.

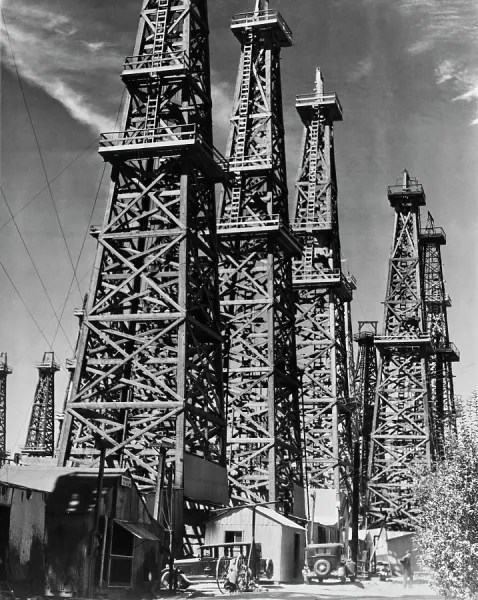

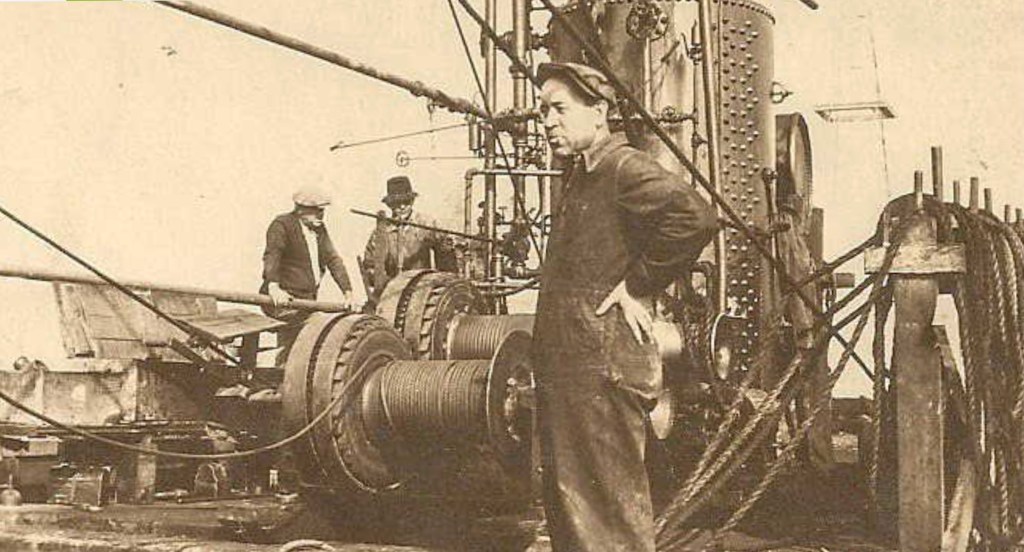

As assistant drilling superintendant Bruce was off the Twelve Hour Tour. Grandma had run the household for most of their married life but Bruce was mostly still away, Running regular tours meant he could be counted on to be at home for half a day at least. Now that he was supervising wells that was no longer true. The automobile had changed the way the company operated. A Tool Pusher could now supervise wells that were far distance from each other. From their home in Hope Ranch Bruce could drive south to Signals wells in Bolsa Chica or Signal Hill or north to the Kern river and operations in the Westside around Taft. Moving was not quite the necessity it once was. Besides, Bruce liked to drive and he found the road not a bad place to be. He even gave his kids lessons on the proper, cool way to go. He said, “Put the wrist of your right hand on the top of the wheel and let the fingers dangle. Let your left arm hang outside the drivers side door and always go as fast as you can.”

The phone hanging on the wall would give its peculiar ring the way they used to do, most people being on party lines where a call for your home would be announced by code, two long rings then a short or perhaps a short and a one long. Most of the job shacks had one now and the roughnecks could call Bruce at home 24 hour a day.

He kept the company car fueled and parked in the driveway so he could get away quickly. Problems at the well couldn’t wait. A shutdown could cost the company volume which was contracted to the refineries and distributors and needed to be delivered to keep the money rolling in.

After fifteen years or so working the rigs the Halls were used to constant movement. The kids knew no other life. My mother, Barbara started the first grade at Bloomfield elementary school in 1924. Bloomfield was a tiny school on donated land, land donated by Fredrick “Sheep” Smith and true to his nickname he grazed huge flocks of sheep on his 360 acre ranch. Once a year he grazed them north to San Francisco, a three months round trip where they were sold to feed a hungry population.

Around the turn of the century “Sheep” donated a block of land for a school to be named after the city in his native Indiana. He wanted a school where his children and the children of his neighbors could get an education.

Mom always referred to the area as Artesia though it would be many years before it would incorporate as such. The Halls lived in a section which was to be called Hawaiian Gardens. A name first used to describe an old fruit and vegetable stand built with palm fronds along what is now the intersection of Norwalk Blvd and Carson St. A local farmer sold his produce there fro a couple of decades and it was rumored that during prohibition you might get some bootlegged spirits along with your fruit if you knew how to ask.

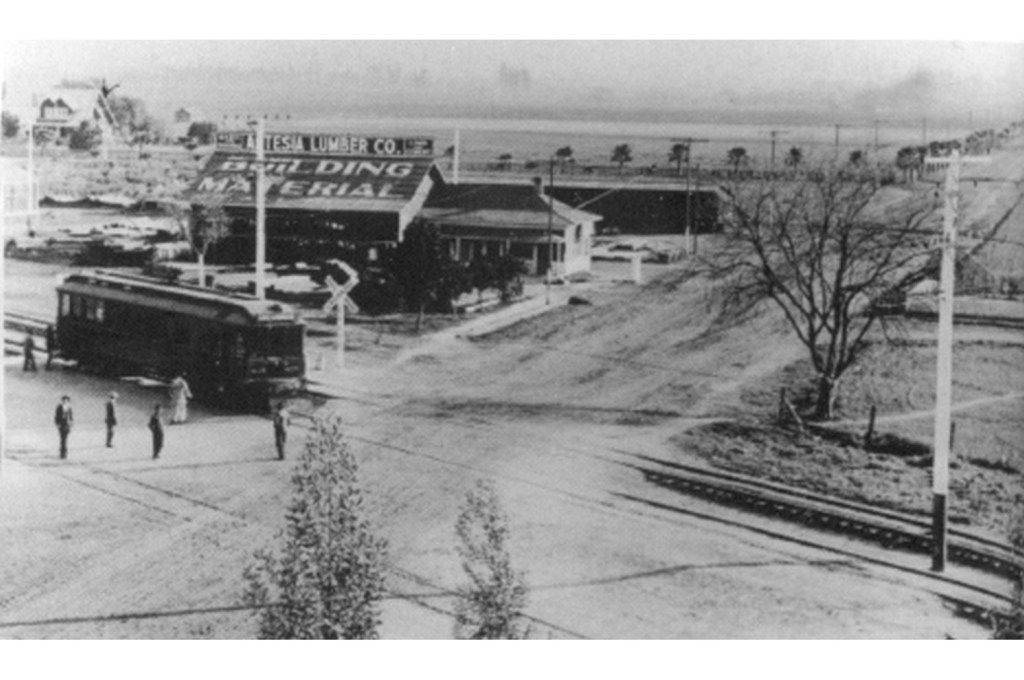

Bruce and Eileen lived out there because after the big discovery well on Signal Hill in 1921 wildcatters were scrambling all over Los Angeles County hoping to strike it rich. The next year, 1922, hoping to alleviate a serious drought in the Artesia area farmers began sinking wells. Artesia was named for its abundant Artesian wells, a nice bit of irony considering that the Los Angeles basin is semi-desert, the drillers quite accidentally struck oil and the boom was on. The little town went from farm and dairy land to oil town in a heartbeat.

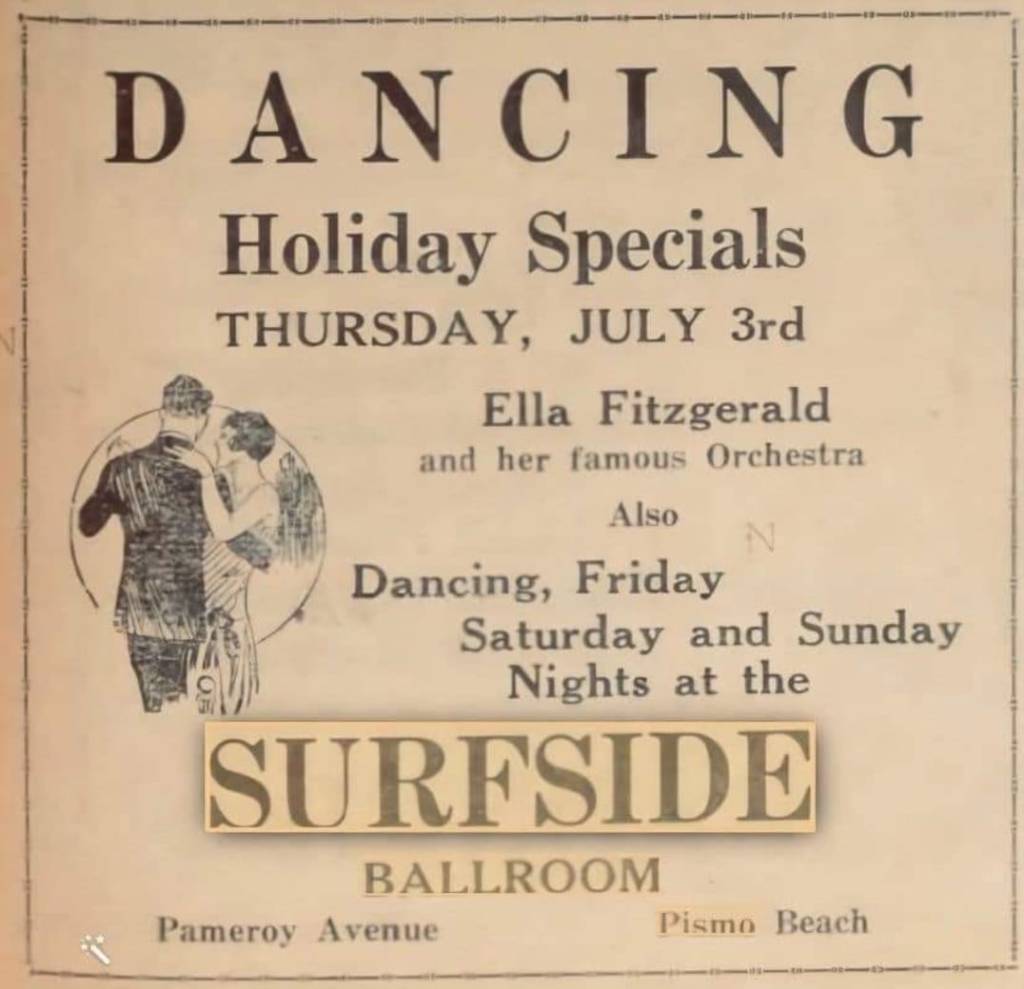

Artesia, Los Angeles County, Ca Artesia historic Society photo about 1921.

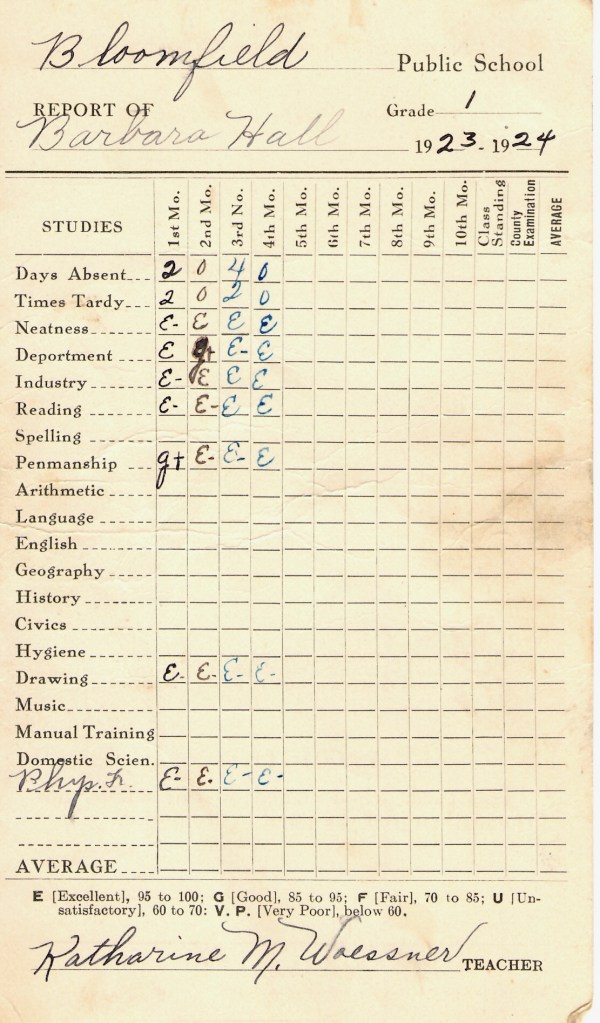

In 1924 the Halls moved down from the Casmalia field and mom started first grade at Bloomfield elementary. From the old photos it looks to be a very new and nice building with a large impressive arcade in the center and two classroom wings, one on each side. Oil booms will do that to a town. In those days people wanted their kids educated, they didn’t care much about curriculum, it was still just the three R’s. It was simple and direct. The old textbooks are pretty narrow in their scope. It was a time before mass production of texts and curriculum which, in a sense has taken much of the personal touch out in favor of cramming as much information down kid’s throats as we can. what they wanted was for their kids to have a better life. Mothers in particular carried much of the weight of running a school. Bake sales, costumes, organizing activities for kids were mostly the work of parents. My mother had a fine hand, which was considered important, she read fluently all of her life. Those grammar school skills were considered to be enough to prosper in higher education and the work place.

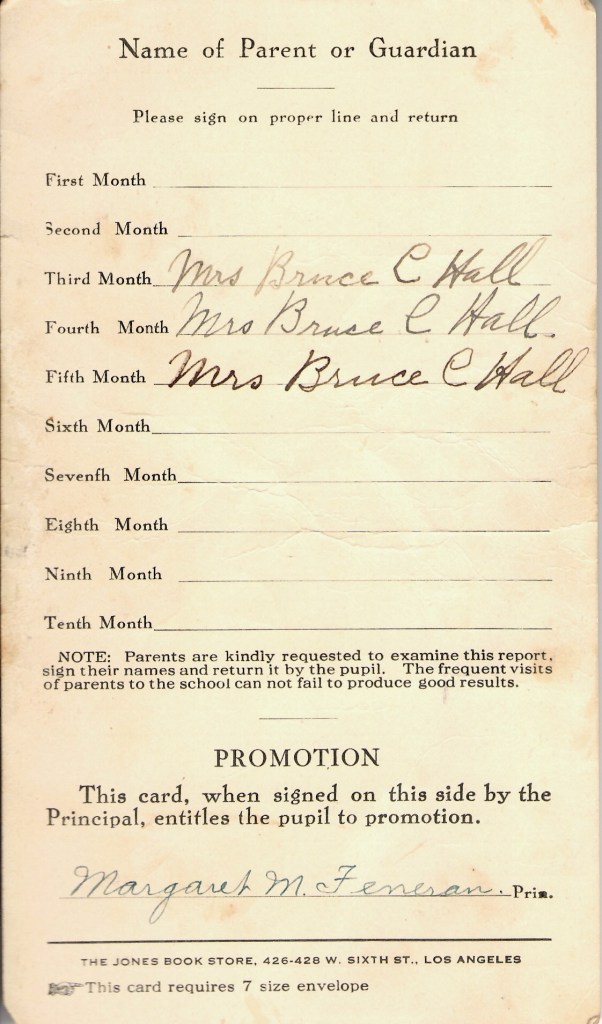

Bloomfield Elementary School 1923-1924 First Grade report card. Hawaiian Gardens, Los Angeles County California.

Take note of the difference in reporting. There are subjects for which she has grades which are no longer on any report card. Also of note her mother had to sign the card and return it to school to be recorded something else which is no longer done.

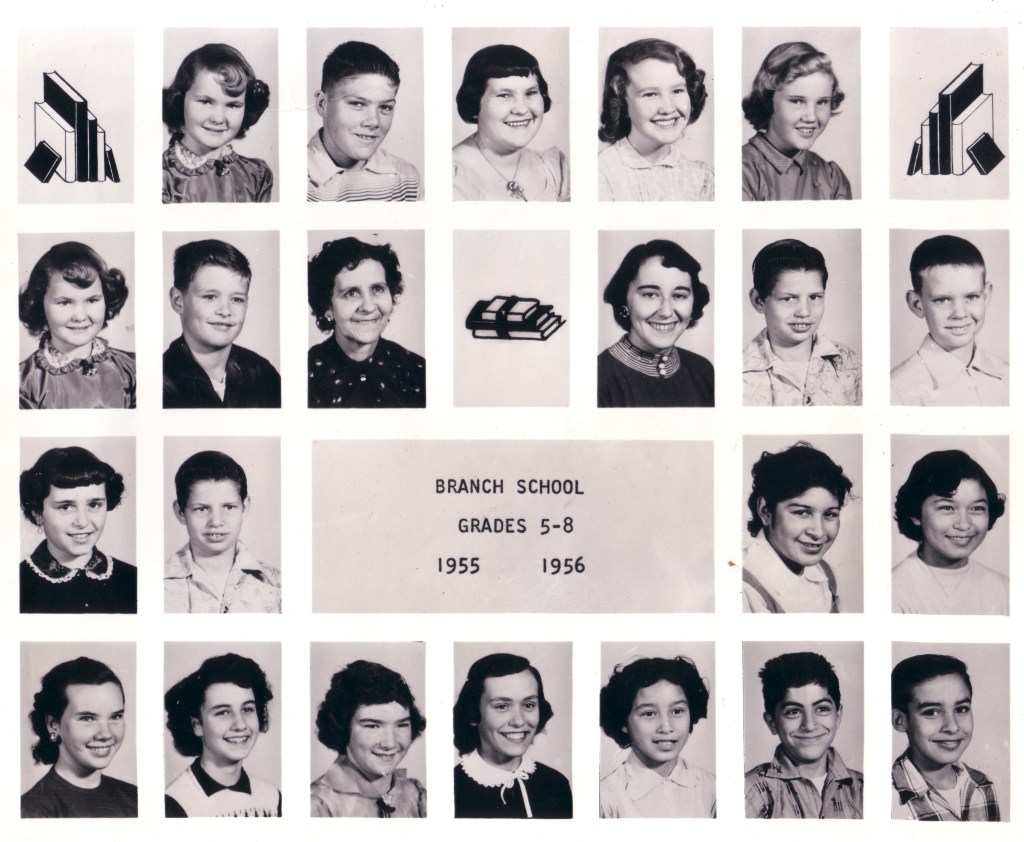

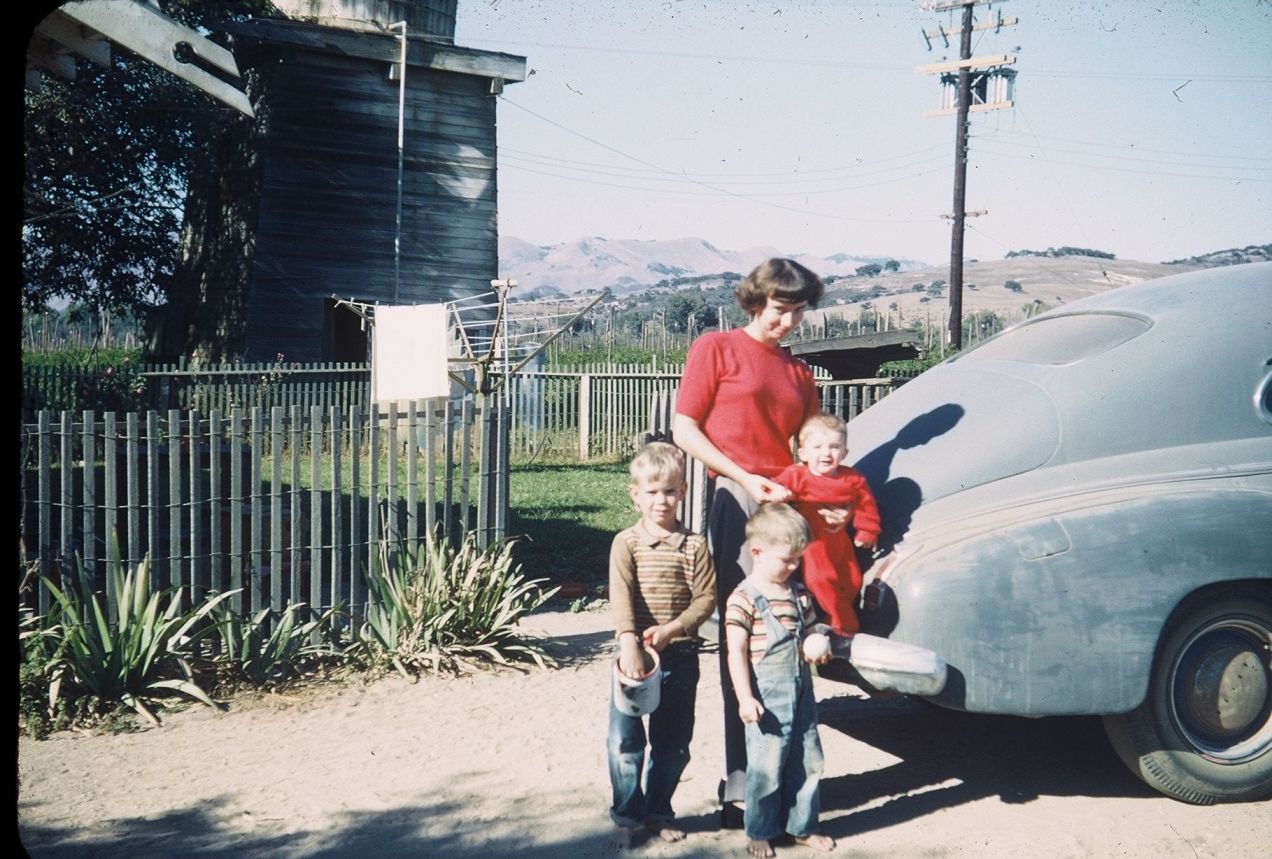

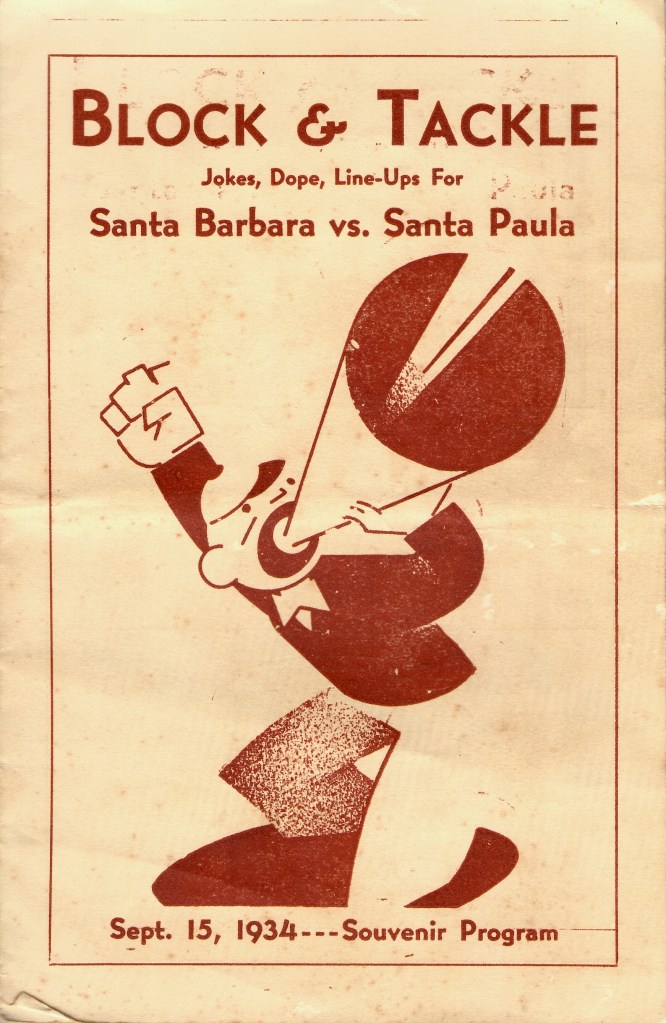

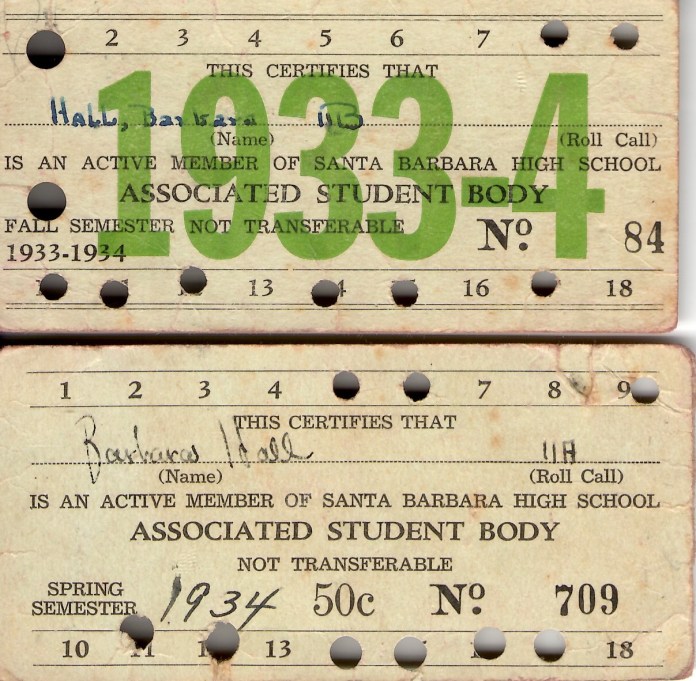

A decade later, back in Santa Barbara where Bruce and uncle Henry were busy whipstocking and slant drilling out off the Santa Barbara channel Eileen and Bruce decided that with his new job at Signal and his promotion, that they would do their best to stay in one place long enough so the girls, Mariel and Barbara could go to Santa Barbara High School for their last two years. It was quite the luxury.

Now that might be all well and good but their itinerant ways remained and a check of census, voting and city directories shows they lived in six different house in those three years.

733 W. Islay, Santa Barbara. A modern photo of the house where they lived in 1933. Zillow photo.

West Micheltorena, North Garden, North Nopal, West Quinto, a P O Box in Goleta and one in Santa Barbara and finally West Cota street near the train station. Other than Goleta they cover an area less than a mile square. Once I asked my dad why they moved so much and he said that grandma hated to clean house which is probably “Apocryphal” but it makes a good story. Maybe there was some small truth to it. It’s a lot of moving.

By ninth grade mom’s transitions from school to school were seamless. Experience and planning with her parents had set the table for finding her way in a new school. If the new school asigned her a first day monitor to show her around she had learned that that girl would not be one of the popular girls and that as she made her tour of campus to keep an eye out for who was popular and who was not.

Up to high school she always knew that if she faced difficulties in school she would be out of there soon. As sad as it sounds she also had to accept that her new friends would soon be left behind. She had walked away from other kids all of her school years and for the first time she had to learn to maintain a friendship.

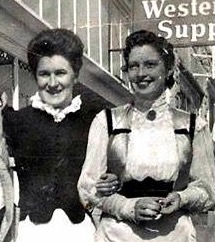

Mom had saved her pennies and nickels and in Santa Barbara she snuck away from the house and walked uptown to a beauty parlor and for the first time had her hair cut and styled. She always said it gave her a lot of confidence, she liked looking pretty and the way it helped her making friends.

Towns like Santa Barbara weathered the depression pretty well. Known a the Riviera of the west it was home to many, many wealthy people who lived in or on the the more exclusive areas. Part of Santa Barbara such as the Riviera, Montecito were filthy with movie stars, authors, business magnates and inherited wealth. Those whose children didn’t go to private schools went to Santa Barbara High. Mom had class with Jordanos, Lagamarsinos, Carrillos, some families dated back to Spanish California. She played tennis at the exclusive Montecito tennis club and loved to tell the story about getting a ride to school in the cream colored Cord convertible of Leo Carrillo, the movie star whose family was one of the founders of the pueblo of Santa Barbara.

High school is where you make some of the friends you will cherish for the rest of your life. She did that too. She went to her high school reunion for the rest of her life.

The yearbook inscription in the opening is from Blanche Belle Baker my mothers life long friend.

Michael Shannon lives in California and writes for his family.