Page 15

Michael Shannon

As the shipped nosed her way past Grande Island and the passing of Spanish Point off to Port she entered the Philippine sea where she picked up the two destroyers who were to be her escorts, the Quartermaster put her wheel over to Port and headed south. From the Philippine sea she swung southeast into the Sulu Sea. A 2 day run saw them turn east at the tip of Mindanao Island passing Zamboanga where the monkeys have no tails* then briefly south through the Celebes Sea until the could swing northeast for the open sea. The ship chugged along at 16 knots, her best speed while the escorts sailed in curlicues, on the hunt for submarines because even in June 1945 plenty of Japanese subs were still at sea hunting. Three days into the run to Guam where they were to pick up more casualties and returnees they passed within just a few miles of the spot at which the Japanese sub I-58 put two Long Lance Torpedos into a speeding cruiser which was not zigzaging but running on a plumb line. The Captain, James McVay was rushing to the Philippines to begin training his crew for the invasion of Japan. He was told there were no Japanese submarines in the area and his escorts had failed to appear so the cruiser was running alone.

The “Indy” leaving Tinian after off-loading the first Atomic bomb. US Navy photo

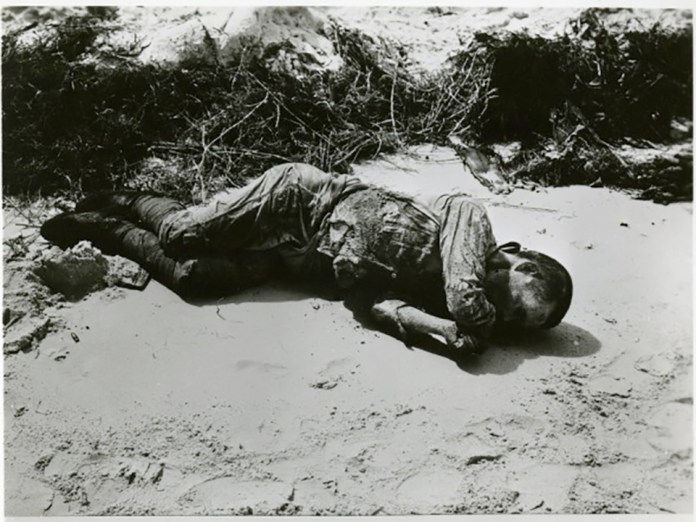

USS Indianapolis CA-35, sank in just twelve minutes. Her bow was blown completely off and the second torpedo exploded in the after engine room and set of the main ammunition magazine. Of 1,195 crewmen aboard, about 300 went down with the ship. The after engine room crew boiled alive from escaping high pressure steam or were blown to bits by the explosion. Off duty sailors in the berthing spaces awoke to darkness and massive amounts of seawater which killed them in moments, their screams drowned in horror. The remaining 890 faced exposure, dehydration, saltwater poisoning, and shark attacks while stranded in the open ocean. With few lifeboats and almost no food or water they were eight hundred miles from land.

The Navy learned of the sinking four days later, when survivors were spotted by the crew of a PV-1 Ventura on routine patrol. U.S. Navy PBY flying boats landed in the rough seas to save those in the water. Only 316 survived. No U.S. warship sunk at sea had lost more sailors.**

Hilo and the rest of men aboard had no idea of the awful drama taking place just a few miles away. They wouldn’t know until the war was over either, for the cruiser had just delivered “Little Boy” to Tinian island the first of the atomic bombs which was dropped on Hiroshima City August 6th, 1945. The delivery was part of the biggest secret of WWII and the Indy was sailing under secret orders and radio silence. No SOS was sent from the ship.

The ship pulled in to Guams Apra harbor where she remained at anchor while more returnees and wounded were loaded. Fuel barges pulled alongside and began refilling her fuel bunkers for the long trip ahead. A repair ship floated at her side and lent the crew a hand in fixing or repairing anything on the list they could. Ships at sea are always broken. A welded ship nearly 442 feet long and rated for 10,000 tons of cargo, the Attack Transports suffered constant flexing and pounding while at sea caused all kinds of damage during operations. Though the Navy crew of 58 officers and 480 enlisted crew worked tirelessly to maintain the ship they could never entirely catch up.

Having traveled nearly two thousand miles, food to feed the crew and passengers was in short supply and barges coming out to the anchorage carried mounds of foodstuff which was winched aboard by the cranes on deck and stored away below. The quartermasters department was kept hopping seeing to the loading and storage of hopefully an ample supply for the rest of the voyage. Feeding and housing over 1,500 men and women returning to the states was a monumental job.

All this food was primarily stored in large, refrigerated and dry storage areas and consisted of both fresh and preserved goods. Cooking was done in massive galleys to produce thousands of meals daily for both the crew and the embarked troops. The logistical system was designed to provide as much variety as possible, though the quality and freshness of the food often depended on the length of the voyage and the availability of resupply.

A ship’s galleys were large-scale, industrial kitchens that operated almost continuously to feed the crew. Cooks, “lovingly” referred to a “Cookie” in the U.S. Navy, worked in 24 hour shifts, 8 hours per watch to ensure meals were available for personnel at all hours.

During long periods at sea, the menus would rely more heavily on frozen, canned, and dried ingredients as fresh supplies ran out. This was always a problem on tropical islands where fresh vegetables were seldom available.

The sailors and Marine would look at the twentieth plate of chipped beef on toast and mutter to themselves, “S**t on a Shingle” again? For veterans, any desire to eat it would be long gone by wars end.

Leaving Guam for the west coast there were some things the troops and sailors could rely on. Chow was going to be monotonous. There would be much standing in line with more than two thousand to feed three times a day and by the time they arrived at the coast of California the mess crews would be like the walking dead, exhausted. For the galley crew these Magic Carpet voyages would be some of the hardest duty of the war for which they would receive scant praise. Perhaps a pat on the back from the Chief mess cook. There was little space for physical activity either, it was just too crowded and most of the passengers weren’t inclined to tolerate much spit and polish or discipline. How does the Shore Patrol or the Master at Arms keep them in line? You can guess. The Master at Arms who is the sheriff of the boat picks equally large and aggressive mates for his department and the officers generally turn a blind eye to the obvious bumps and bruises meted out in lieu of Captains Mast. Most Captains think that is a fair trade.

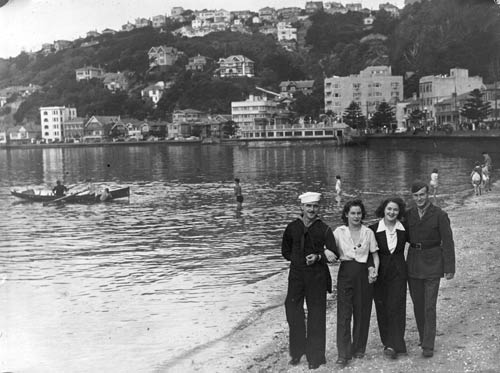

As always, things on A deck where the officers were housed was pretty plush, it was white table cloth, sterling silver and high quality food served by friendly Filipino stewards in white gloves. This increased the enlisted man’s mortal hatred of officers. While those below ate their monotonous meals the officers ate meals that were hardly less elegant than first class passengers had been served in more peaceful days. For supper it was dress whites or Suntans, shoes polished by the same stewards who served them and polite conversation. On some returning ships there were even army and Navy nurses to break the monotony and add to the hatred of the privileged. Most soldiers hadn’t seen an American woman in years and likely wouldn’t see those aboard their own ship.

What infantrymen know is that officers for the most part never share a foxhole with a Dogface. Few officers above Lieutenant ever get any closer to the fighting front than they can avoid. Those that did were revered but they were few. The thousands on the main deck or herded below seethed with bad will at the injustice of it. A famous phrase that came out of WWII concerned “old Blood and Guts” General Patton of whom his own troopers in the 3rd army were wont to say, “Yeah, his guts , our blood.” There are newsreels of him standing up in his staff car, ivory handled pistol on prominent display, speeding down the muddy roads of France, splattering mud on the tired an dirty troopers walking alongside and jauntily wave and pumping his fist in encouragement. Hardly a Doggie bothers to even look up. He slept in a French Chateau with Marlene Dietrich, they slept on the open ground under a dirty wool blanket. Hatred was putting it mildly. A pretty universal sentiment in the military wherever you went.

The last part of the voyage was over 6,000 miles, a quarter way around the globe. The attack transports had been hard used and most had never returned to Mare Island in the San Francisco bay for serious overhauls, they’d had to make do with bandaids and bailing wire. The boiler tubes were warped and caked with scale. Much engine room machinery was just capable of limping along at reduced speed. There were no places in the vast distances they were traveling where they could just pull over. The high speed destroyers racing around on patrol, duty they hated, it was monotonous and crews were frustrated by these voyages. They wanted to get ashore too. The navy was crewed by farm boys, mechanics, shoe salesmen and soda jerks, they were not or ever intended to be lifers. Their officers were reservists and would mostly go ashore once the war was over. Lifers were the men who manned the transport ships, civilian Merchant Mariners who had or would spend a life at sea. They shared the same dangers but the sea was their life.***

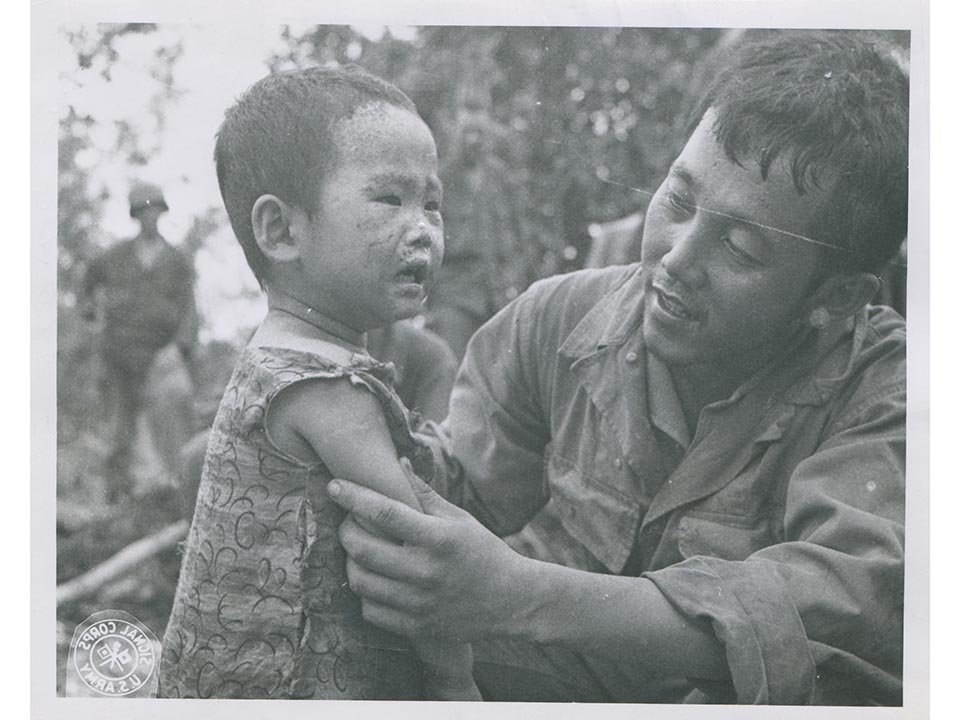

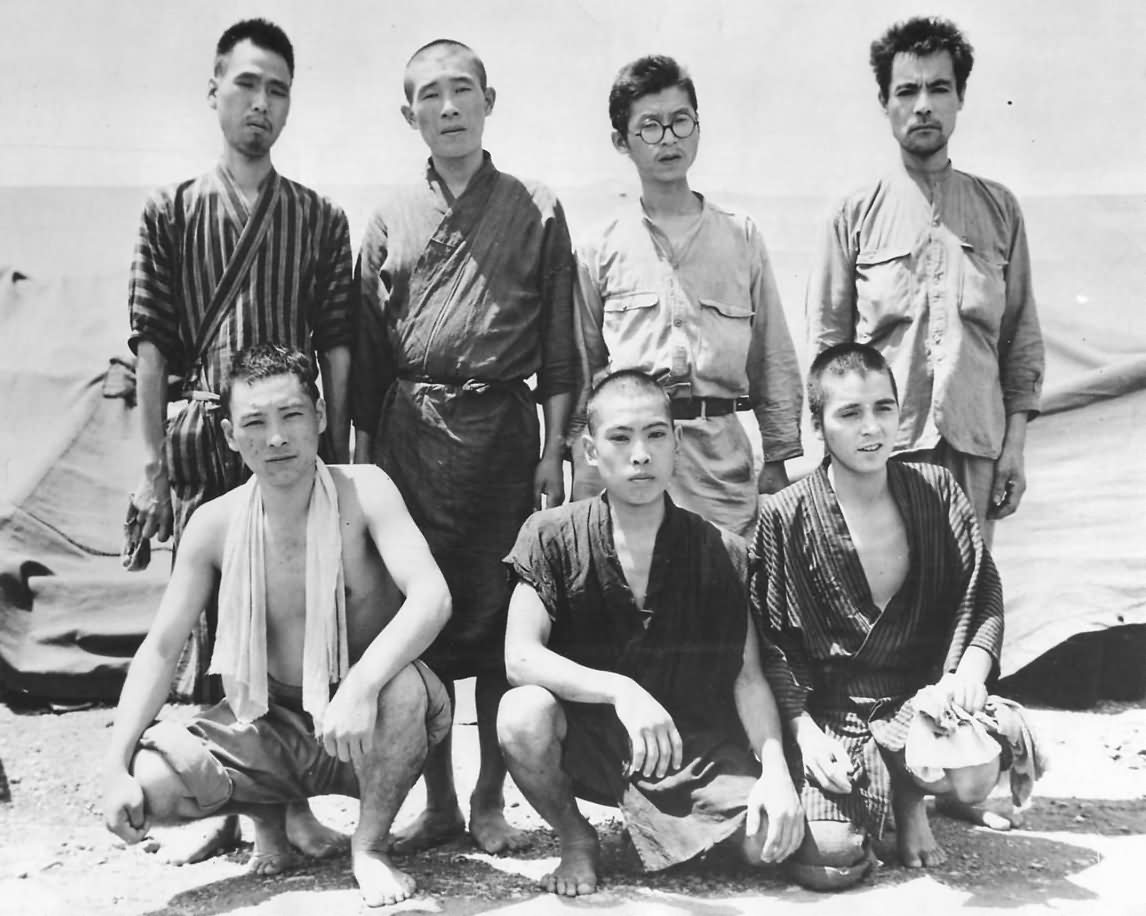

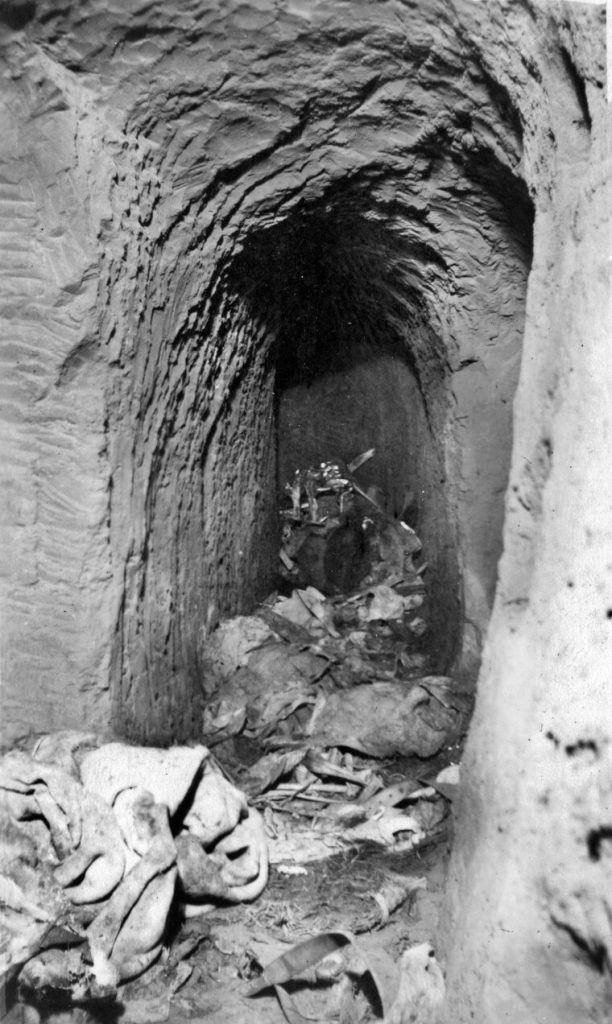

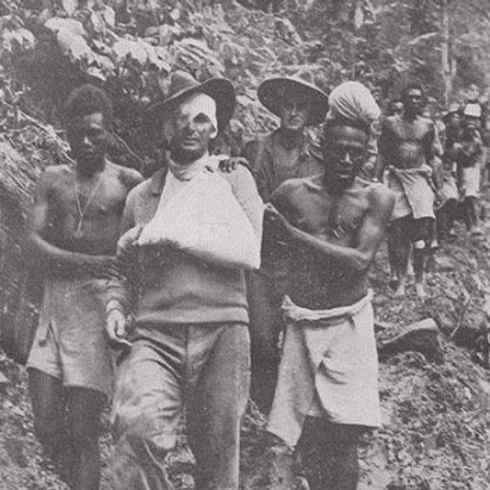

In the weeks at sea, Hilo and his mates were not afforded any special accommodations like the trip out in ’42. No more converted ocean liners for them, no private berthing, they were now veterans and their value to the army and marines were well understood. Though the MIS service was classified the people they worked with in the field knew what they did, they had seen them coaxing prisoners out of caves and half-destroyed pill boxes. They had crouched in foxholes with Marines and soldiers while the air buzzed with rifle and machine gun rounds. They had saved thousands of live across the Pacific. They had proven themselves.

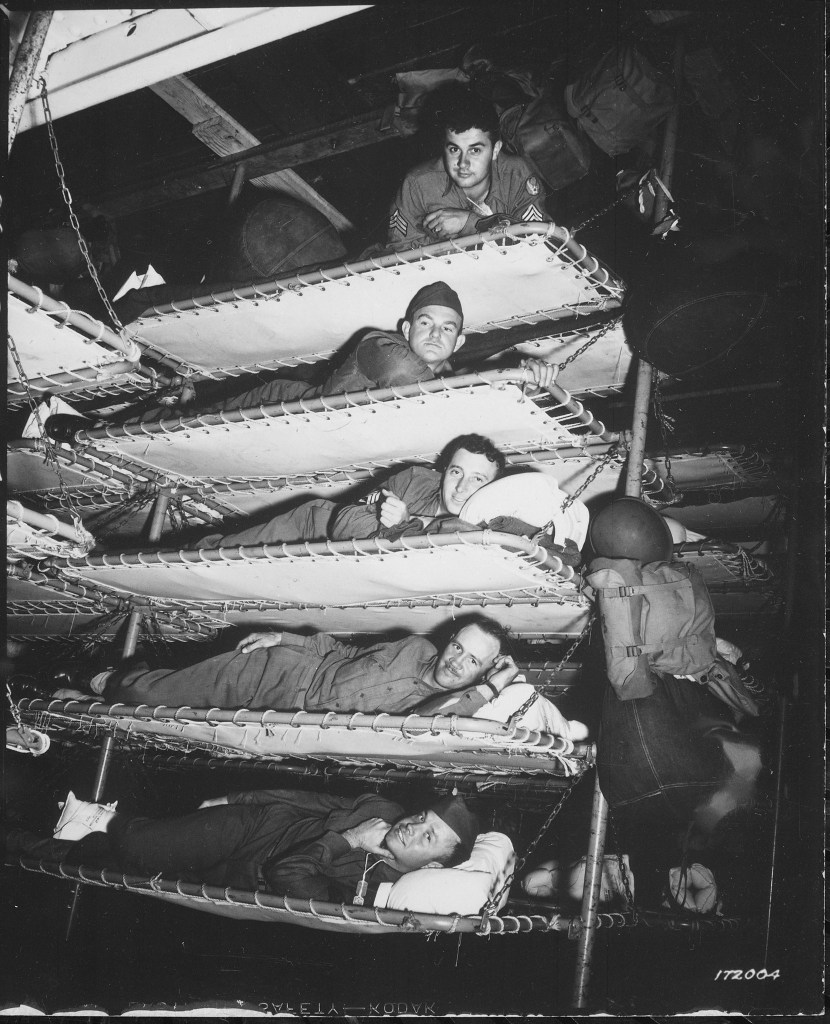

First Class accommodations. USN photo.

The most serious way to pass time at sea in a crowded ship was to sleep, play cards, roll “Dem Bones, or fight, of which there were plenty of takers. Books were rare though the ships had a small library and by the time they pulled into Long Beach Naval Base people were reading the instructions for operating machinery printed on the bulkheads. They read mattress tags, read and re-read letters from home until they literally fell apart, they read each others letters.

Without thinking the were putting away the memory of war and replacing it with the possibilities of the future.

Traveling the southern route in July and early August they were likely spared any serious bad weather but the monsoon in the southern hemisphere generated long swells which traveled north across the equator. smoothing out and lengthening in to long rollers that marched across the mid Pacific like ranks of soldiers. The Pacific or Mar Pacifico, the “Peaceful Sea” can be anything but. Named by Ferdinand Magellan as he crossed the southern hemisphere to his eventual fate in the Philippine islands. He passed day after day on a smooth almost oily ocean with most days, just a faint ripple of wind. The voyage from Patagonia to Guam took three and a half months. To quote Coleridge:****

Day after day, day after day,

We stuck, nor breath nor motion;

As idle as a painted ship

Upon a painted ocean.

Coming at right angles to the ships course they caused her to roll from Port to Starboard and back again. The motion caused some serious sea sickness. The old saying about seasickness is absolutely true. “At the first you think you’re going to die, by the second day you want to die.” By the time the ship reached the vicinity of the west coast near Point Conception on California’s western shore it drifted in a miasma of farts, the odor of unwashed bodies, their clothes and a skim of dried vomit coating her berthing spaces. No one had any desire to linger aboard.

Turning eastward into the Santa Barbara Channel the voyagers could, through the almost ever present fog clinging to Point Conception, poking into the Pacific like spear at the turning of California’s coastline from north-south to east-west, faint as a dream the sere brown and tan hills of home spattered by the greasy green chaparral, the hard dark green of coastal oaks and perhaps best of all the smell of home. Hardened soldiers and sailors were seen to cry.

Point Conception California. Hank Pitcher.

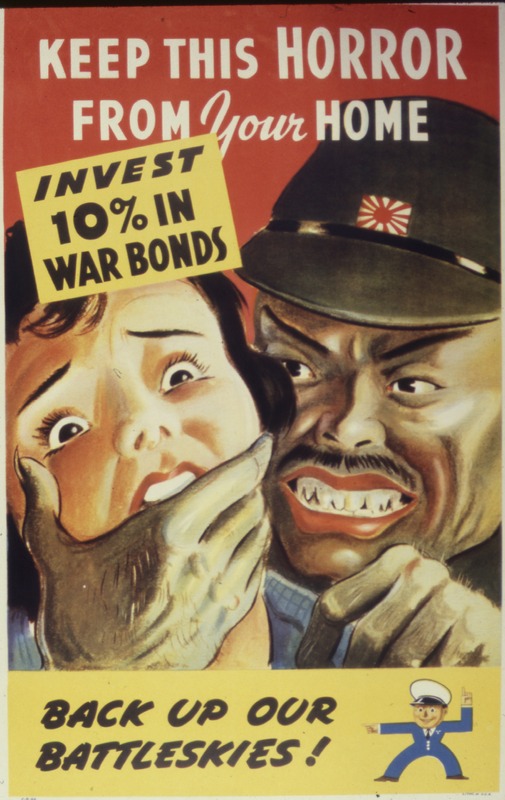

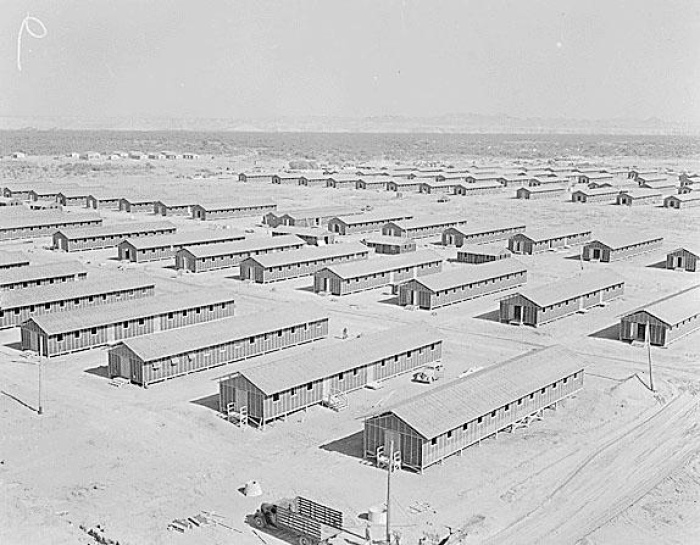

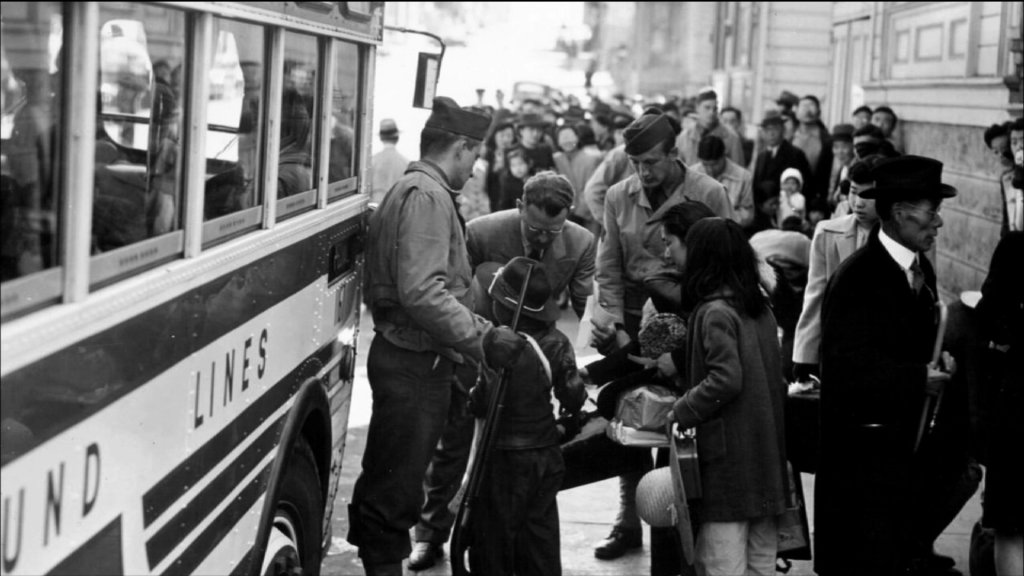

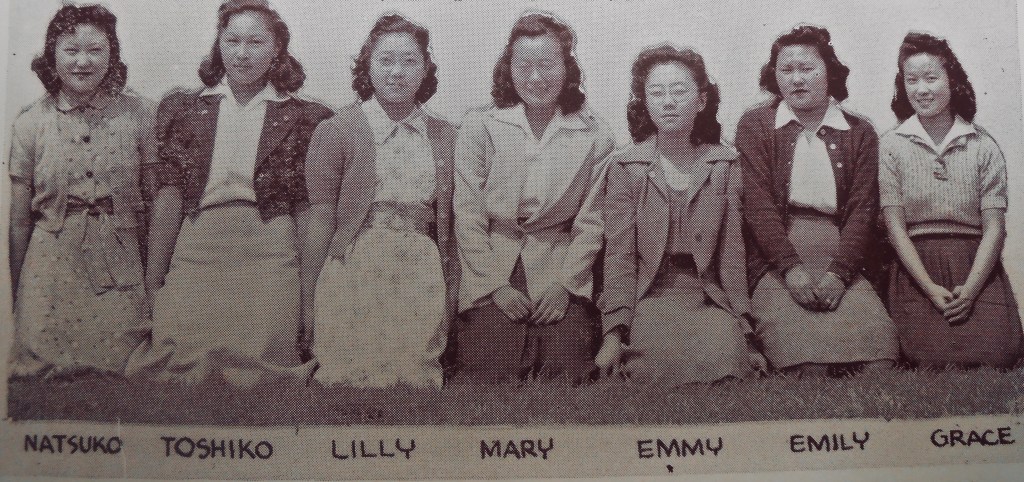

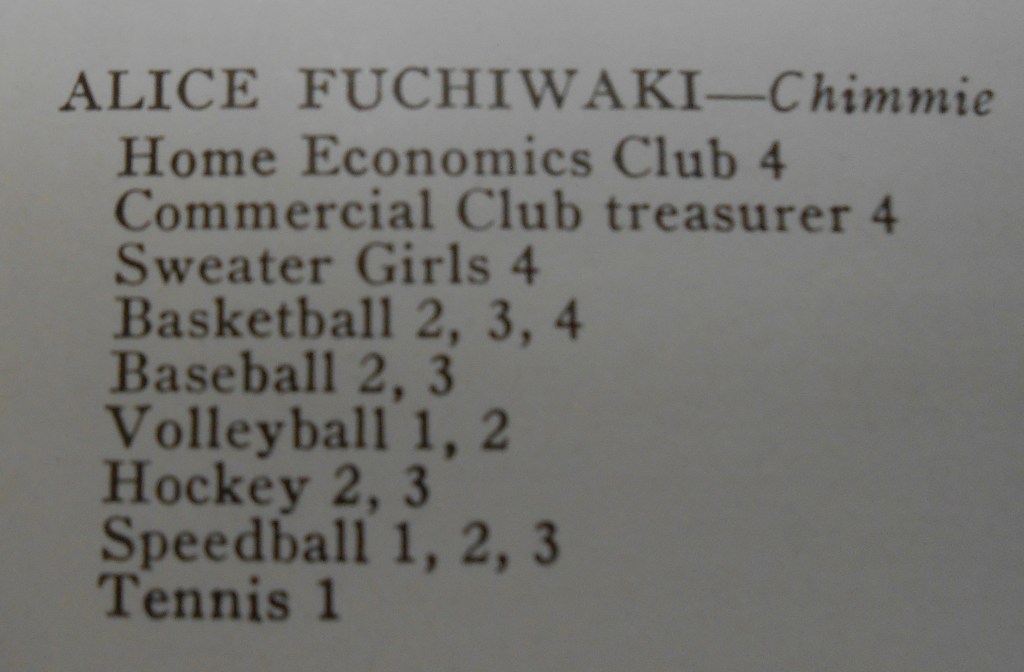

Hilo could not have been an exemption. He had been away for nearly four years. He could not have known exactly what to expect. He did know that the country he was returning to was an unknown place. His family was still in the concentration camp in the Sonoran desert of southwest Arizona, his Arroyo Grande friends scattered to the four winds. Where, exactly was home anymore?

Homecoming.

Page 16 of Dear Dona is next.

Cover Photo: returning troopship, Operation Magic Carpet, 1945

*”The Monkeys Have No Tails in Zamboanga” is the official regimental march of the 27th Infantry Regiment, as the “Wolfhound March”. The lyrics of this official version were written in 1907 in Cuba by G. Savoca, the regimental band leader (died 1912), after the regiment was formed in 1901 to serve in the Philippines. According to Harry McClintock, the tune was borrowed from an official march of the Philippine Constabulary Band, as played at the St. Louis Exposition in 1904. One version was collected as part of the Gordon “Inferno” Collection. As with many folk songs with military origins (such as “Mademoiselle from Armentières” from World War I), the song becomes a souvenir of the campaign for those who served. See below

**In the movie “Jaws,” Quint the shark hunter relates his experience as a survivor of the USS Indianapolis CA-35

***The Merchant Marine suffered the worst losses of World War II. During World War II, the U.S. Merchant Marine suffered high losses, with about 9,521 mariners perishing out of over 243,000 who served, representing a higher percentage casualty rate than any branch of the U.S. military. These losses occurred from enemy submarine, mine, and aircraft attacks, as well as the dangerous elements at sea, with 733 American merchant ships sunk and 609 mariners captured as prisoners of war. The US government ruled that they would receive no veterans benefits though their casualty rate was only slightly less than the Marines. In 1988 partial benefits were offered primarily for schooling but not on the scale of “Combat” veterans. Though sailors serving in wartime take an oath and are paid by the government they were not considered true servicemen. The author served in the Merchant Marine in the early 70’s and shipped with many veterans of WWII. Ask a man who was torpedoed twice in the Pacific if he considers himself a veteran.

****”The Rime of the Ancyent Marinere.” Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Written 1797–98

Oh, the monkeys have no tails in Zamboanga,

Oh, the monkeys have no tails in Zamboanga,

Oh, the monkeys have no tails,

They were bitten off by whales,

Oh, the monkeys have no tails in Zamboanga.

Chorus:

Oh, we won’t go back to Subic anymore,

Oh, we won’t go back to Subic anymore,

Oh, we won’t go back to Subic

Where they mix our wine with tubig, (Water)

and on and on…

Michael Shannon is a Navy veteran and former Merchant Mariner. He lives in Arroyo Grande, California