Chapter Two

Michael Shannon

Jack was a clever man so as he packed up the rolling stock and his village, carefully placing each piece in one of the old milk crates stamped with the family’s label, Hillcrest Farms Dairy. As was his nature, being a man who does nothing half way he began to ruminate on how he could continue his railroading.

After running the dairy for thirty years my grandfather was retired. No more 4:30 am cow calls, no more bottling, no more deliveries, he had time on his hands for the first time in his life. At 70, his “ready to go” nature needed an outlet.

The old dairy barn was semi- abandoned, the milk cows were gone and to boot, there was the huge stack of clear heart redwood planking that was left from the collapse of the main silo many years before. An idea was germinated. Why not just move his trains up to the barn? It had electricity, overhead lights and an attached workshop where he could tinker as much as he wanted. What my grandmother thought of this we don’t know but she could hardly have failed to see that it would get him out of the house. After forty six years of marriage, outside was where she was used to him being. She offered no argument.

There is a thing about small towns that many don’t know or remember. Small numbers means that neighbors are, well, neighborly. The glue that holds them together is an unwritten law that precludes people who are acquaintances mind some of their own business. Much depends on that. The grocer and the butcher and their wives and children are people you know. The school teacher, the farmer, the hotelkeeper and the constable are all on a first name basis. You can apply the Mark Twain saying, “A lie travels right round the world while the truth is still getting its shoes on.” People are careful with gossip. It’s someone you know. Everyone needs something from someone else.

It’s not as if normal human behavior is somehow missing in small communities. There is a man who is the love child of two seemingly ordinary people, both married. The state representative is having an affair with the woman down the street. A woman on Nelson St was referred to as a “Sexaholic” by my mother. There is a dairyman who waters his milk and the county treasurer is about to go on trial for embezzling. There is racism, Whites, Japanese, Filipino, Portuguese, Mexican get along in public but there are things said in the privacy of kitchens that prove otherwise.The elders in my family surely knew of these things, yet kept those discussions inside the home and certainly never in front of children.

Going to a small rural school where all these people were represented never seemed to be an issue. Racism is taught. If you are not taught you’ll be happier.

Keeping the lid on the kettle was important to most folks since people not only knew other people but likely knew their antecedents too. When a man like Jack needed help he could get it. Personal relations was the glue that kept communities together.

L-R, George Burt, Jack Shannon, unidentified, George Shannon and Clem Lambert. Family Photo

In the dairy business you needed labor year round from boys and young men who were children of people they knew. When I was a young man I knew many adults who would invariably say, “I worked for your grandparents when I was a boy.” They were full of high praise for the way they were treated. The bus driver who drove me to high school was one. His name was Al Huebner and he had worked haying for my grandfather. There was Clem Lambert, a mechanic, George Burt, builder and Mayor, Deril Waiters, an electrician and builder, Addison Woods, another contractor and many others who had cut their teeth in the hay fields or the milking barn before the war. When you talked to them they would remark that what they got was worth repayment. Pass it forward to a new generation. I worked for some of them because of him. Jack and Annie had banked, if you will, a heap of good relations that they could now call on for his railroad.

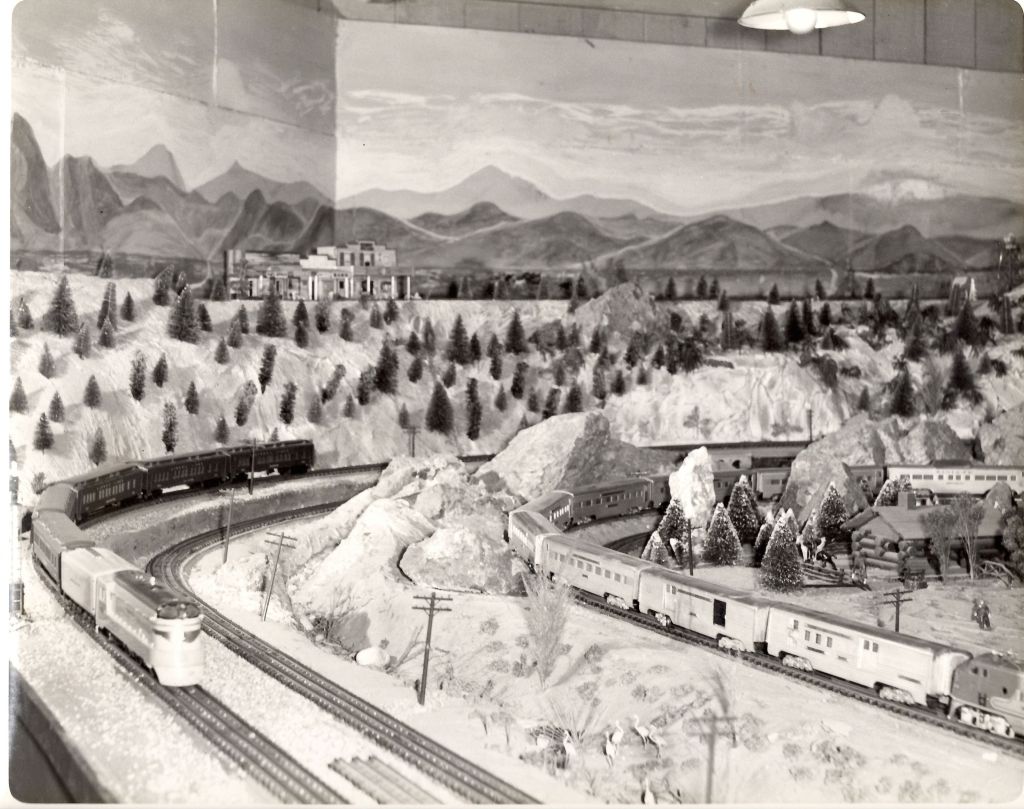

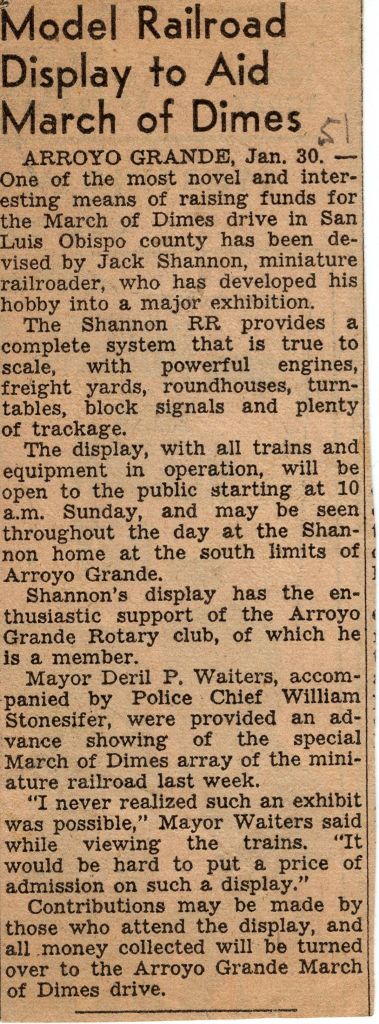

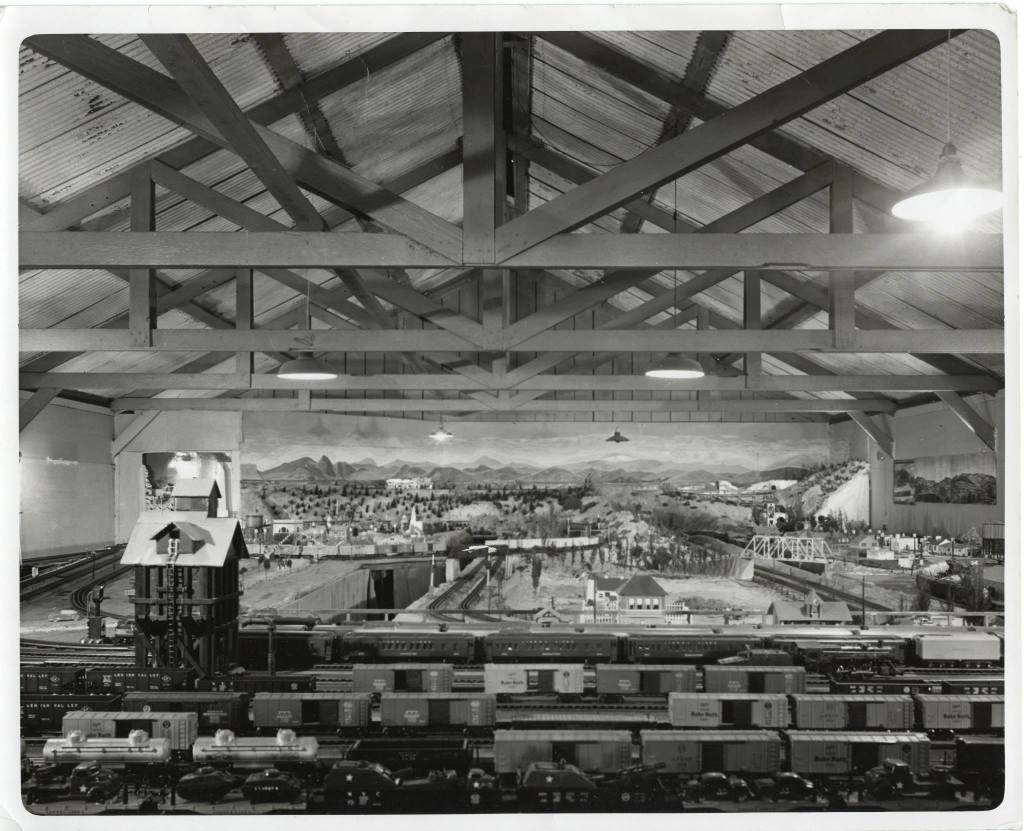

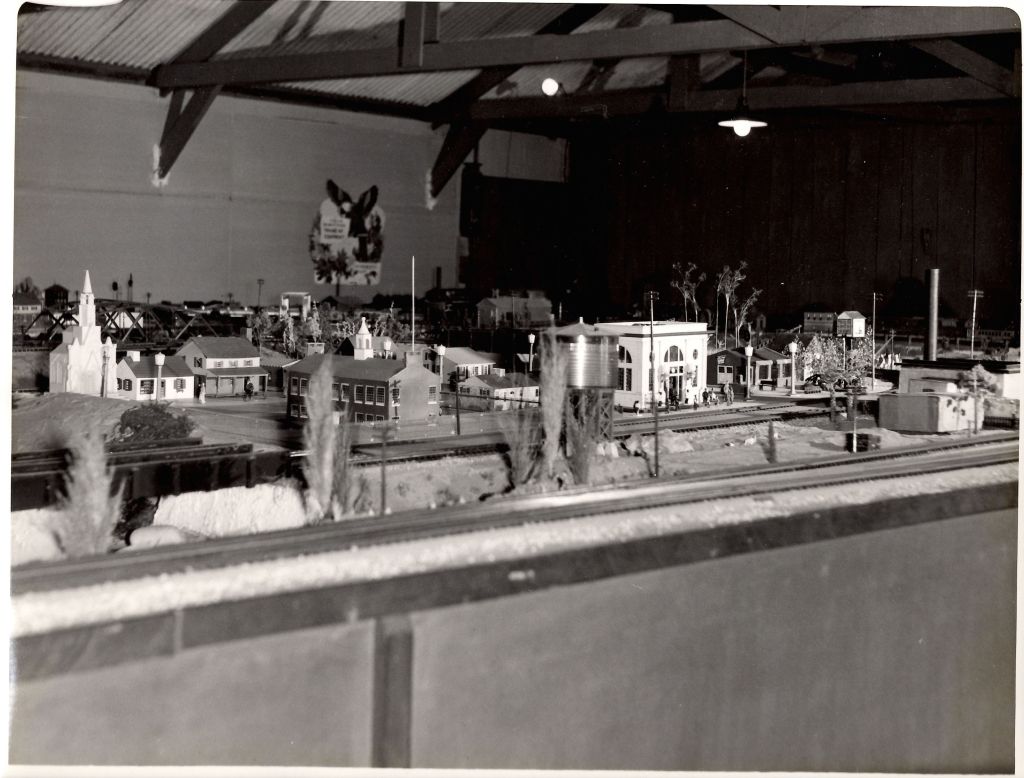

A plan was made. The old cow barn would be the place where his trains ran. The girls were all gone so the barn was empty and just needed a little work to be ready. All the stanchions were torn out. A load of sheetrock was ordered from Leo Brisco’s lumber yard and they covered all the windows and walls to give the interior an nice clean, white surface. They then took all the redwood from the old silo and built a table that covered nearly the entire interior, leaving just a walkway around three sides. My mother came in with her paint brushes and painted a backdrop at the one end.

The Hiawatha and the Super Chief under the big sky. Family Photo.

Deril Waiters helped my grandfather lay out all the electrical wire needed for the switches, building lights and interior lights in the little town with it’s church, hardware store and tiny little homes. All of that was connected to a myriad of switches, toggles and the transformers which would run the trains. The men built chicken wire mountains and plastered them. They built hills, gullies and rivers too. My mother painted and painted. Grandfather built a round house. I thought it was funny because he used toilet paper rolls for the many chimneys on the roof, each one designed to collect the exhaust of the locomotive below. He built a turntable and even stuck a little enameled worker at one end to operate it when a locomotive needed to be run in or out.

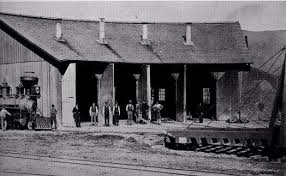

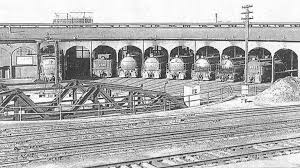

Pacific Coast Railroad and Southern Pacific Roundhouses San Luis Obispo, California

We knew roundhouses. San Luis Obispo was a division point on the Southern Pacific and had a large one along with the shops needed to maintain all the rolling stock. He knew that things were rapidly changing and the big roundhouse would soon be gone so he took me one a road trip to see it. We also plowed through the weeds to see the ruins of the old Pacific Coast railroad yard down on lower Higuera Street. Long abandoned, the shops and warehouse were just the kind of things to tempt a little boy no matter his age.

Apparently this was a family thing because my dad took us on trips to see things that would soon be gone forever. We rode the last ferries across San Francisco Bay, we stood next to the huge Big Boy locomotives as they watered at the little station at Madeline up in Lassen county. My parents friends lived on a ranch there that belonged to Tommy and Billie Swigert. The RR stop was just up the ranch road. When you’re barely four feet tall those engines are monsters. In those days the engineer let kids walk right up to them and touch.

Southern Pacific’s Alco 4-8-8-4 “Big Boy” at Madeline, Lassen County, California. Barbara Shannon Photo.

We went down to Guadalupe to see the great train wreck. A diesel unit pulling freight passing through the Guadalupe yards clipped the rear of the tender on a cab forward 4-8-8–2 Southern Pacific cab forward locomotive and made a huge mess. My grandfather drove me down in his big green Cadillac Sedan Deville and we simply walked through the site. There was train debris everywhere. Trucks with their great steel wheels, journal boxes bleeding grease, Boxcars split by giant can openers, Barrels and crates strewn about, steel rails twisted, ties tore apart already pushed into piles by bulldozers. the Diesel unit’s cab crushed and on its side, the steam locomotive the same. Huge railroad cranes hooking up to the rolling stock in order to lift them free of the tracks. No one seemed to notice us, a grandfather and his little grandson wandering across a train wreck site. Maybe it was the suit he wore or the Caddie, he looked important so he must have been. Afterwards we went for ice cream.

The Southern Pacific Railroad sponsored train rides for many years. Cub Scouts, 4-H and many local school kids took the short ride up the Cuesta courtesy of the Railroad. My grammar school, Branch Elementary would, a few years later, take the last steam locomotive ride up over the Cuesta grade to Santa Margarita. A picnic at Cuesta Park afterwards and the ride home in our mothers cars. The last steamers were then retired and the Diesel-Electric took center stage. Parents and teachers told us about “The Last Thing.” but it doesn’t register when you are so young which in a way is a sad thing. We should have been able to savor the experience when it was happening. Perhaps my grandfather felt the same way. He was born a horse and buggy man when serious travel was by train. For him, those were all the past.

Work on the trains moved along. They built the table from the old silo’s redwood. Removable plywood skirts were added which could be removed in order to work underneath the table. 4 oz duck was glued to the table top just as it was for the mountains. paint was brushed on, trees and vegetation glued into place and fake water filled all the streams and rivers. Many of the houses, autos and trucks were simply bought at the dime store.

I don’t think my grandfather ever attacked anything as a casual endeavor. The family observation was that when he “Made hay, he made hay.” I grew up hearing this and I believed it then as I do now.

Dad would go out to help on Sundays, the farmers only day off, and give us reports at dinner. Occasionally my grandfather would drive out to our farm, pull his big car into the back yard gate and come into the house with a big box of donuts from Carlock’s bakery. He would be peppered with questions by his grandsons and was happy to give us detailed answers though how much of that sunk in I don’t know. It was exciting though. It was hard to imagine even with my little train set chugging round and round on our living room floor circling my mothers hand made braided rug.

After months of anticipation Dad took us out to see the completed project. He parked by the geraniums planted next to the big silo, painted a pink tone, a mix of barn red and white because as was the custom on our ranches nothing was ever wasted if anyone thought it might have some future use. At the top were the faded letters that spelled Hillcrest Farms which were once bright and clear but now after the wars rationing of paint, slipping away. Those years saw the gradual end of local dairies because the big Knudsen Dairy Company had moved into Santa Maria and started buying up the locals, in effect forcing them out. They would all be gone by the mid fifties, so why waste paint?

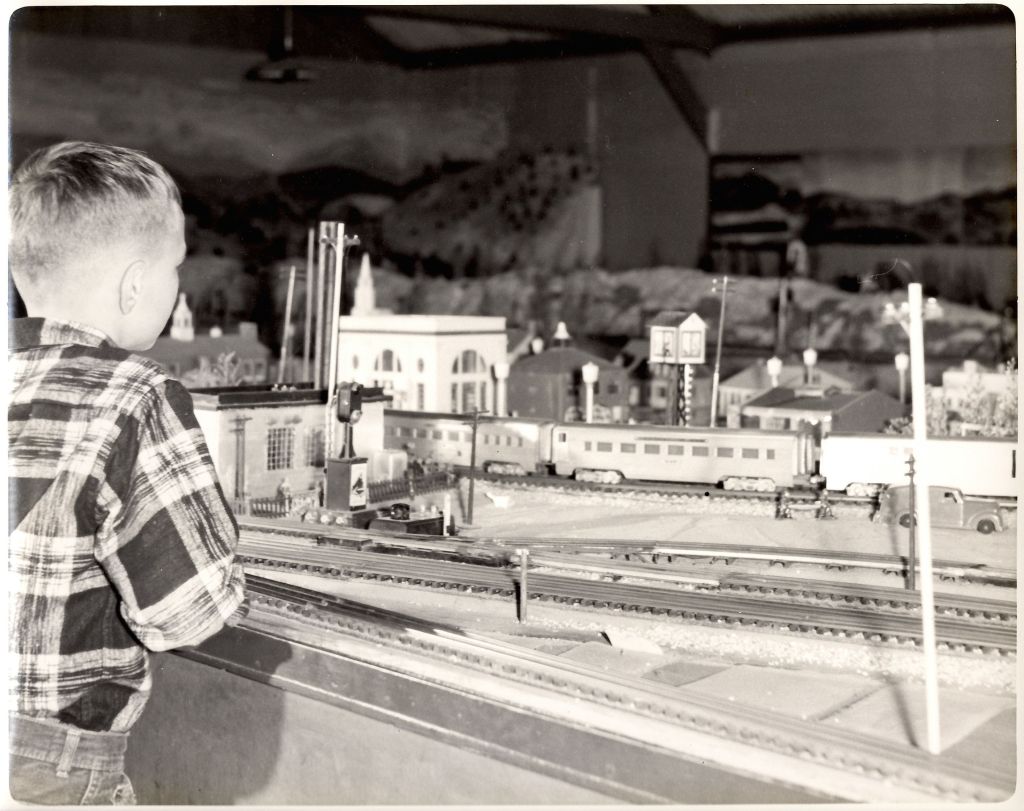

The great rolling door to the dairy barn was pulled back and we scampered up the steps, my dad lifting my little brother because his legs were still too short to do it on his own we entered the cool dark space. My grandfather flipped the old porcelain light switch which made a crisp snap and all the hanging lights came to life. And there it was. What a glorious sight for a little boy. I had, for my pleasure, the largest privately owned “O” gauge train set in the state of California.

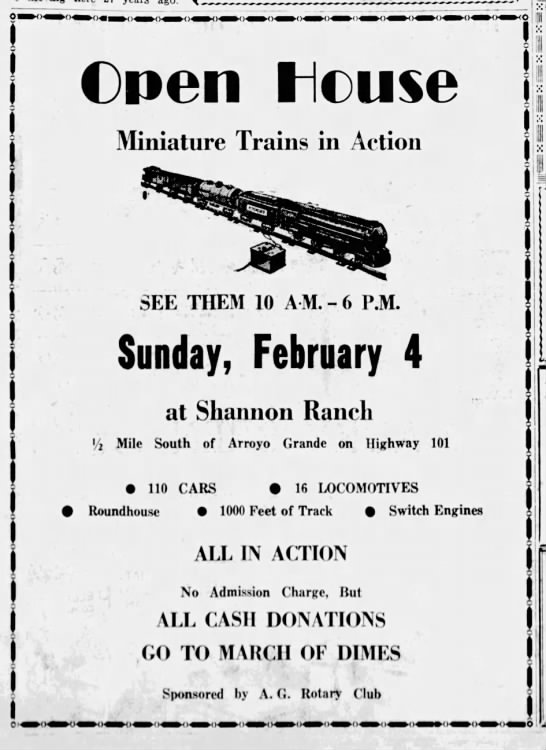

There are those who still remember coming out to the ranch for the March of Dimes fundraisers in the fifties. Sponsored by the Rotary Club, my grandfather a member, the lines would literally stretch out the door with people and their kids. Over the years it was occasionally open to the public and was viewed by thousands of local kids. Much to their delight for those that remember it. Arroyo Grande was still awfully rural then and kids were pretty limited in possible experience.

Sad to say, my grandfather, by now pushing seventy five found it hard to maintain, old barns are not very clean and dust and chaff from the corrals deposited a layer of dust that had to be continually cleaned. Toy trains still used steel rails then and the cracks in the walls and around the doors allowed in enough moisture to continually coat the yards and yards of rail with a fine coast of rust which had to be ground off by hand using a block of pumice. Without good electrical contact the locomotives simply would not run. The hours I spent crawling around grinding away with my stone weren’t that much fun but there was no one else who could do it. The compensation was, of course, learning to operate several trains at once, switch boxcars in the yards and best of all spending a lot of time with my grandfather.

Dad would take me out in the morning after breakfast and drop me off at the barn where I did my track maintenance until noon. Jack would bundle me into the big Caddie and it would make its stately was along the highway frontage road and up the hill the house, where my grandmother would have a lunch laid out for us, baloney sandwiches with Mayo and the cold, cold milk she kept in the yellow Fiestaware jug she kept in the fridge. I felt very grown up when my grandfather offered me “A Cuppa Jo” which I accepted just as if I was all grown up. Boiled on the stove he and my grandfather would take theirs poured onto a saucer from the cup and mine would be liberally laced with sugar and milk. What a treat. Afterwards a little nap and then the return trip.

I’d earned my engineers license in the morning and we would spend some time at the bank of big black Bakelite transformers driving the New York Central’s Hiawatha and the Southern Pacific Daylight passenger trains around and around. We ran the little Yard Goats, making up freight trains, parking under the coal chute and moving locomotives in and out of the round houses. We could wind the key in the little church and the bells would call to service. In the corner was an old record player and grandpa would put on a record that played the sounds of passing trains and the heavy staccato exhaust of the big locomotive starting a train. He taught me how to synchronize the sound with the little trains on the layout. He said it had to be just right. There was no speeding or crashing of trains. Everything had to be just right. It was not apparent to me at the time but lessons were being learned about hard work, rewards and all things proper.

Years later when I returned to Arroyo Grande from my own adventures, both my grandparents had gone to heaven. I went out to the barn and opened the door and viewed the forlorn table, cleared of all the trains and track. Only the hole where the round house turntable once was, was left. The mural my mother painted on the back wall was a fresh as ever. Nothing, really, was left. It had all been sold years before, my grandfather just gotten too old and let it all go. All a memory now.

You can’t imagine how that felt to the grown man who cherished the little boy and his grandparents.

The Jack Shannon Railroad 1953. Family Photo.

Jack Shannon lived to be 96 years old. A long and busy life. He was born in 1882 in frontier Reno, Nevada, and grew up in Arroyo Grande California. His life spanned from the horse to a man on the moon. Just marvelous don’t you think?

Linked to Chapter one. https://wordpress.com/post/atthetable2015.com/12395

Michael Shannon lives in Arroyo Grande, California.