Michael Shannon

“Bee Jackson was a honey. The Bee’s knees, the original. She was the Berries…..an ankling Baby, the Cat’s pajamas.”

The photo, Beatrice “Bee” Jackson (1903 – 1933) was an actress and dancer. She was born in Brooklyn, New York and grew up in Bound Brook, New Jersey. Her mother was a former actress. As a child, Jackson loved to make up dances to the music of her toy phonograph.

She was known as the Charleston Queen, and while she didn’t invent the dance (some believe the dance originated from an African-American dance called the Juba), she was one of the dance’s most prominent advocates. Blonde and vivacious, Bee Jackson had the world in the palm of her hand. At fifteen years old, she was a chorus dancer in the Zeigfield Follies. Eventually, she toured Europe, had royalty chasing after her, and was a member of high society. A celebrity of the highest degree, Jackson’s legs were insured for $100,000, almost 25 years before Betty Grable did it.

She danced through her early years with her favorite toy, a phonograph. ‘I danced because I loved it’ she said and simply worked out steps to her favorite tunes even though she had no conception of routine; that intricate pattern that is weaved into a dance.

Bee’s mother, Grace Jackson, a former actress, acted as her manager and influenced her decision to focus on the exciting new steps. The popularity of the “Charleston” dance was taking off like a skyrocket in 1924. At that moment, Bee was at, or at least very near, the epicenter of the phenomenon and was equipped with the right skills to capitalize on its success. She was just one average dancer among a herd of competitors, however, and she needed a clever angle to carve out a path to fame and fortune. Their solution was to strike out as touring act and show the dance to audiences far beyond the Big Apple. To increase Bee’s marketing appeal, she began presenting herself in 1925 as the originator of the “Charleston” dance, or at least the person responsible for transferring it from South Carolina migrant former slaves to New York and the white community.

She might not be a household name any more, but images of Miss Jackson have been reproduced in hundreds-perhaps thousands-of books, magazines, and webpages devoted to the effervescent “Roaring Twenties.”

My mom and her sister Mariel were right on time. The best of pals, born just a year apart. They were oil patch kids and moved from place to place in California depending on where there father, a Driller happened to be sent. My grandfather said they lived in every God forsaken town in southern California. The oil business was populated by some pretty rough characters. Out on the lease you never knew what you were going to get. There were pistols carried, a sheath knife was de riguer both for the work and perhaps to settle a dispute. Most roughnecks, a perfect name for the men who traveled looking for work, mostly single, not much education and half exhausted most of the time. Add the booze and the hootchie coothie girls and things were ripe for trouble. My grandparents never liked living on the leases mostly to protect their three kids.

They were pretty lucky when the girls were entering their teens, most of the work of my grandfather stretched from Huntington Beach north to San Luis Obispo county. They bounced around a lot, Compton, Long Beach, Belmont Shores, Artesia, Signal Hills, Bolsa Chic and Wilmington , wherever there was a rig, they were.

In those days Los Angeles had a street railroad mock lovingly dubbed the Red Cars. The red may have been flashy when they were new but that had long since faded to the color of a red shirt too long washed and worn.The electric street cars were everywhere and for small change you could ride from Balboa out to Redlands or up as far as San Fernando, a thousand miles of track that covered all of Los Angeles county.

Pacific Railway was a private company originally built by the company to promote new suburbs in the outer reaches of the city. It was a boon to property developers and served it’s purpose for many years. The rise of the automobile eventually drove the line into bankruptcy.

LA is the quintessential car city. This is ironic, given that LA was built around the largest electric railway system in the world. The suburbs that you see all over greater LA, the 1920s copy-pasted bungalows which are everywhere, were designed to function in tandem with the old Pacific Electric Railway. You can still see the traces today. For example, if something is named “Huntington”, like Huntington Park, Huntington Beach, the Huntington Library and so on, it’s pretty likely named after Henry Huntington, the Pacific Electric Railway’s owner.*

In my mothers teenage years most kids did not own cars. It was the Red Cars or nothing; or you could walk. It was only 33 miles from Long Beach to downtown.

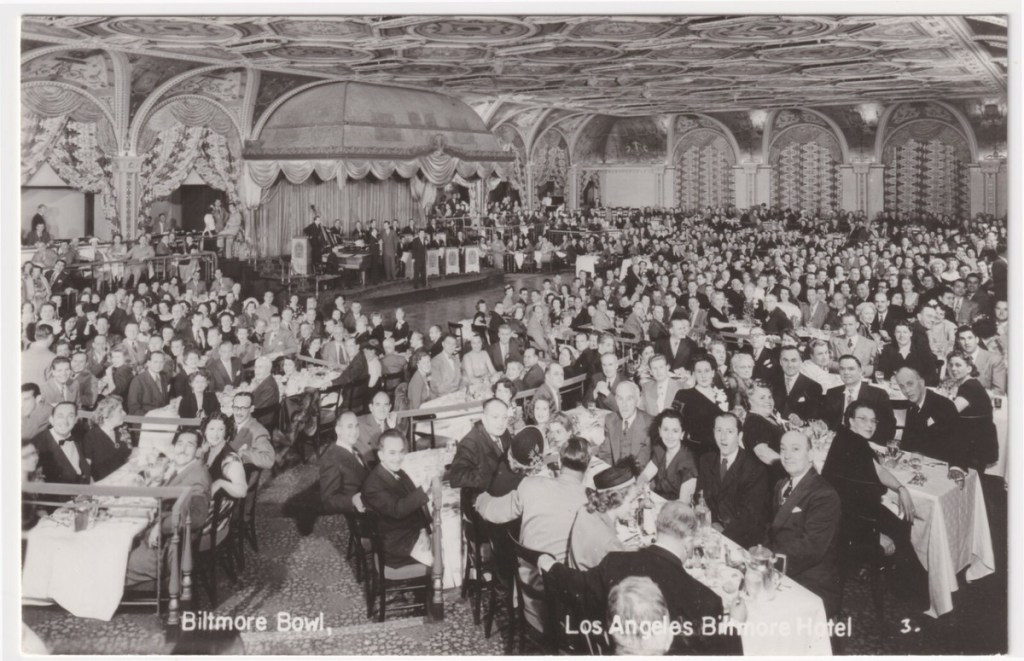

So my aunt Mariel, my mother and their friends like to hop the cars and rattle around all the hot spots of the time. On weekends they would go dancing at Santa Monica or Ocean Park or best of all all the way to the Biltmore. In downtown LA the Biltmore Hotel was the largest hotel west of Chicago. Built in 1923 it was considered the finest in California. With more than a thousand rooms it was located opposite Pershing Square in the heart of downtown.**

Most importantly for my mother and her friends was the basement nightclub known as the Biltmore Bowl. With it’s two story ceiling and with a size that would accomodate 2,000 dancers and guests, it had hosted 8 Academy Awards ceremonies since its opening. Saturday nights it would be standing room only. The girls played dress up trying to look like stars themselves. Oh so suave, smoking in the days fashion, mom said they were swivel necks looking to see if any famous Hollywood stars were to be seen. The saw Olivia De Havilland and Lucy and Ricky Ricardo on occasion.

Dancing was the point though. Dressed in their best they nursed their Ginger Ales, mom said that the Shirley Temples were too sweet and “Icky” a sentiment echoed by Shirley herself.

The depression was the heyday of the big bands, Artie Shaw, Benny Goodman or the Glen Miller touring orchestra belting out the hits of the day. Artie Shaw’s Begin the Beguine*** just as smooth as velvet, begging you for a dance. My mother spinning across the floor, ankle length skirt swirling, hem clutched in one hand her low heeled pumps gliding over the corn starched floors, head flung. back hair flying and smiling to beat the band.

Exhausted girls sleeping in the Red Car, piled like tired puppies dreaming of future glamorous nights.

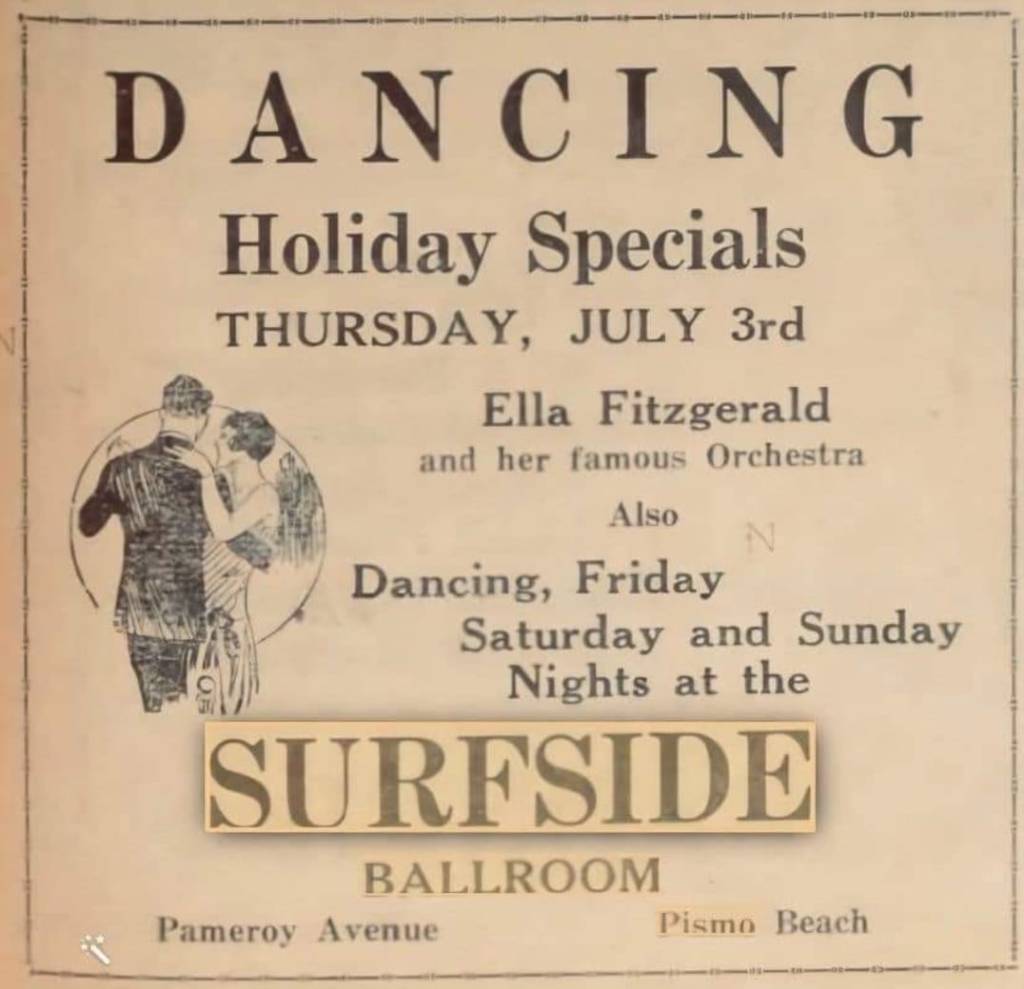

When my grandfather was transferred to Arroyo Grande in 1940 she met my father. While they were courting they used to take his little grey Plymouth coupe down to Pismo Beach to go dancing at the Pavilion. Though Pismo was a tiny little town it had it’s full compliment of Saloons, bars and dance halls. A soupcon of titillating danger hung over it all, especially at the beginning of the war when herds of soldiers from all the military bases flocked to the place. My Dad always said was where the “Debris meets the sea.” There was anything a young man from the sticks could imagine. Pool halls filled with slickers, the filipino gambling halls with, convenient cribs out back and the Beer bars like Mattie’s where, dressed in a silk blouse and velvet trousers. she would hustle those boys by buyin’ the first round for free and pointing out her apartment building down by the pavilion where her Taxi dancers dwelled.****

During the war masses of soldiers in training meant that the ballrooms and dance halls did a booming business. There was no slackening of business for the big touring bands like the Dorsey Brothers and Benny Goodman who swung through town on their way to the big cities. Every forty miles or so there was a stop on the railroad as they traveled around the country, from Tijuana to Seattle and points east.

It’s hard to imagine my Dad trippin’ across the floor but he was a young man in his prime, loved to write music and was captivated by this glamorous girl from the big city. If she wanted to go dancing, they would.

Barbara Hall and husband to be George Shannon 1943.

Fast forward to 1960 and as Kevin Bacon so aptly said, “lets dance.” Boys entering teengedom needed to learn to shake a leg. Mom was right there. She put on an old vinyl record that she kept in the huge piece of furniture, the squatting beast of Cherry wood the television lived in, along with it’s companion the radio and phonograph. In the cabinet below were records kept and carried for decades. Dance tunes, crooners like Der Bingle, Bing Crosby whose hot buttered voice poured like chocolate syrup when he sang. As music went he was the be all and end all of music for my dad who looked on Sinatra and Elvis fwith suspicion. Not so for my mother.

She had me help her roll the hooked rug in our living room. She mopped the wooden floor boards underneath and when they dried she sprinkled cornstarch across it.

She turned to the cabinet, swung the needle arm, set it on an old, old record so brittle it might crack at a hard look. A quick move to the toggle to start and the high pitched tone of clarinets sprang from the speakers clothed with that nubbly brownish fabric sprinkled with flecks of gold spun music like the notes in a Disney cartoon.

Bum bump, bum bump, bum bumpa bump bump bump, the beginning notes of the Charleston jumped from the beast with the beat that moved the feets. I stood facing her as she danced, stopping every so often to explain what to do.

She taught the Lindy Hop, named for Charles Lindbergh’s hop across the Atlantic, the Black Bottom, the Fox Trot and how to Waltz. She could even Twist.

“Shake it, shake it, Baby, let’s do the twist,” yeah, a forty two year old farm wife, a woman with her hair in rollers, dressed in peddle pushers, apron swaying with the beat, shoes slippin” across those old hardwood floors of the house I grew up in. I can still see her. Close your eyes and you can too.

*Henry Edwards Huntington (February 27, 1850 – May 23, 1927) was an American railroad magnate and collector of art and rare books. He settled in Los Angeles, where he owned the Pacific Electric Railway and substantial real estate interests. He was a major booster for Los Angeles in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and many places in California are named after him. His uncle Collis P. Huntington became one of The Big Four who built the Central Pacific Railroad, one of the two railroads that built the transcontinental railway in 1869. His greatest legacy is the world famous Huntington Library Museum in San Marino California. He is buried in the gardens there. https://www.huntington.org/

**Pershing Square is a small public park in Downtown Los Angeles, California, one square block in size, bounded by 5th Street to the north, 6th to the south, Hill to the east, and Olive to the west. Originally dedicated in 1866 by Mayor Cristóbal Aguilar as La Plaza Abaja, the square has had numerous names over the years until it was finally dedicated in honor of General John J. Pershing in 1918.

***Begin the Beguine, Artie Shaw, written by the inestimable Cole P rter,https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cCYGyg1H56s

****Taxi Dancers is a term applied to young women who danced for a dime at dance halls. “Dime a Dance.” It was a flexible world if you know what I mean.

Cover Photo: Beatrice “Bee” Jackson

Michael Shannon is a writer, surfer and traveler. He writes so his children will know where they came from.