Page 5

By Michael Shannon.

The group of sixteen translators from your dad’s class arrived by train at the siding in Pittsburg, California. Pittsburg was the major debarkation point on the west coast for those heading for the Pacific War Theater. After a week confined to barracks at camp Stoneman, Hilo and his fellow graduates found they would be leaving by ship in a few days. They could see the skyline of San Francisco shimmering under clear sky’s just across the bay but were not allowed to visit owing to the high commands orders that all Nisei be confined to base for their own safety. The danger from their fellow soldiers was real, particularly the Marines who were across the bay. To prepare Marines for what was coming all Japanese were brutally vilified in speech and print. Such indoctrination is common to all wars no matter the country. Propaganda yes, but no less dangerous especially to those who had not been exposed to combat yet. There had been several serious incidents where Nisei in uniform were assaulted by groups of soldiers and sailors. Feelings ran very high.

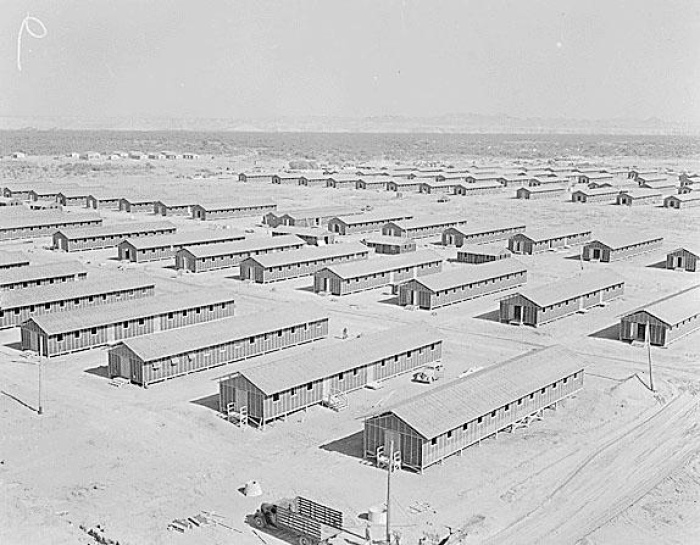

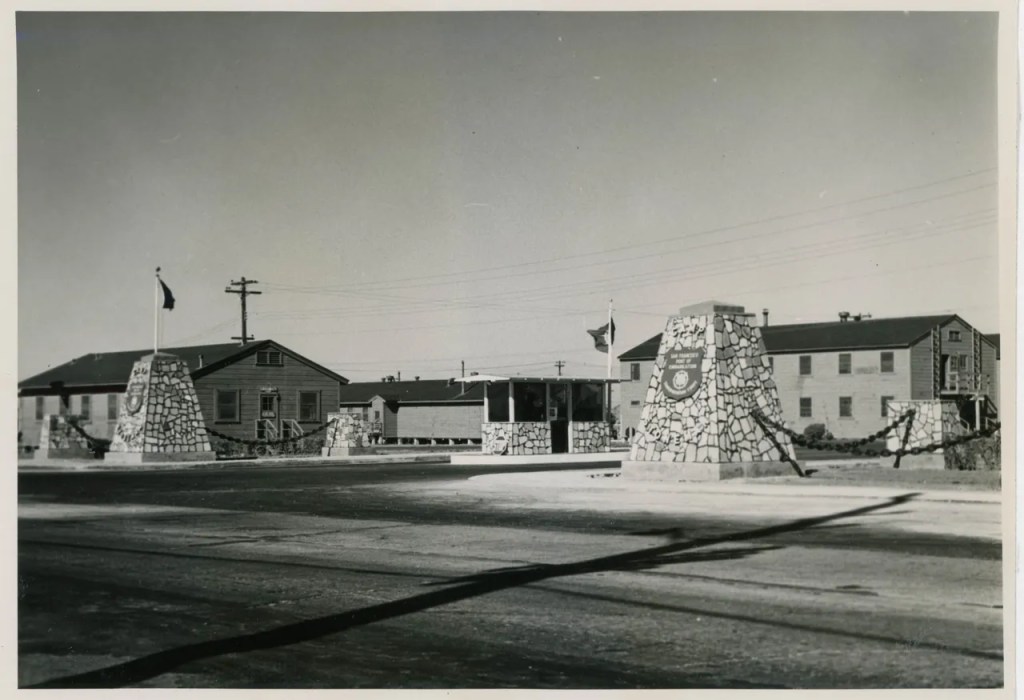

Camp George Stoneman, Pittsburg, California, 1943. National Archives

Stoneman was brand new, completed just two months before your dad arrived. The camp was named after George Stoneman*, a cavalry commander during the Civil War and later Governor of California. In addition to almost 346 barracks (63 man), 86 company administrative and storehouses, 8 infirmaries, and dozens of administrative buildings, the 2,500 acre camp held nine post exchanges, 14 recreation halls, 13 mess halls, a 24 hour shoe repair and tailoring business, one post office, a chapel and one stockade. Overall, the camp was a city unto itself. It had a fire department and observation tower, water reservoir, bakery, Red Cross station, meat cutting plant, library, parking lots and 31 miles of roads. For recreation, Stoneman boasted two gymnasiums, a baseball diamond, eight basketball courts, eight boxing rings and a swimming pool and bowling alley. Officer and enlisted clubs provided everything from reading rooms to spaghetti dinners. The camp also contained the largest telephone center of its day, with 75 phone booths and a bank of operators who could handle 2,000 long distance calls a day. Stoneman even had USO shows featuring stars such as Groucho Marx, Gary Moore, and Red Skelton. Lucille Ball once donned a swimming suit to dedicate an enlisted men’s club.

Camp Stoneman had a maximum capacity of 40,000 troops and at one time ran a payroll of a million dollars per month. Leaving camp to the docks where transport ships waited meant departing the camp at the California Ave. gate and marching down Harbor St. to and catch the ferry at Pittsburg landing. Many “Old Timers” recall the day when they would shine shoes, sell newspapers, round up burgers and and cokes in service to the troops to earn some coin. It is said that when the troops were departing or being “shipped out” they would toss their remaining coins or dollars to the local children as their was no longer any need for American currency where they were headed.

Camp Savage was pretty small by comparison and the Nisei soldiers must have been amazed. Mostly farm boys from California or fisherman’s sons and plantation workers from Hawaii, Stoneman dwarfed old Fort Bliss. The fort covered half the acreage of the entire Arroyo Grande valley and had forty times it’s population.

After a week the men were told to pack and be ready to catch a ferry across the bay to pier 45** where they would board for an unknown destination.

Foreground, pier 45, 1943. U S Naval vessels in background.

The Army and the Navy had chartered dozens of passenger ships from home fleets and foreign flagged companies. Operating out of San Francisco were several that had flown the company flags of the Dollar Line,*** American President Lines and the Matson Line. Famous luxury liners in the Hawaii trade such as the SS Lurline, Monterey, Matsonia, Maui and the Malolo were now being operated by the US Army Transport Service. These ships in particular, because of their size and speed were referred to as “The Monsters.” Just three of them, They traveled alone, rarely needing warships for protection as most naval vessels couldn’t match their speed. This was considered protection enough from Imperial Japanese submarines. They could also make the 6,725 nautical mile trip to Auckland, New Zealand without refueling. Thats where they were headed though only the Captain knew it. Everyone else was in the dark.

USAT Lurline pulling out of San Francisco, fully loaded with over 6,000 soldiers, sailors and Marines. US Heritage Command Photo. 1943

Steaming under the Golden Gate bridge and out past the Farallone Islands she left the treacherous Potato Patch to port and headed southwest. She picked up her escorts, three Fletcher class destroyers and the Cruiser USS Indianapolis. The officer of the watch rang up full ahead on the telegraph, the engine room lit off all the boilers, smoke poured from the stacks, bow wave arched higher and they headed for the sunset.

The Nisei found their quarters for the trip and were pleasantly surprised. They were to stay in two converted first class cabins on the promenade deck. A pre-war cabin for a trip from San Francisco to Honolulu cost $200.00 in 1940. ( $4,509.49 today ) The boys joked that they were getting a really good deal. They also felt lucky because they knew the berthing decks where the soldiers were stacked as much as six high in their pipe bunks breathing the odorous air, a mix of cigarette smoke, and dirty smelly clothes. The ships laundry was out of operation for the trip. There were too may passengers, so going on deck for some fresh air had to be done in shifts. Likewise chow. You stood in long lines for hours in order to eat. Almost as soon as the ship hit her first Pacific roller, the unbelievably foul smell of vomit began sluicing around the below decks. There were pails but they soon overflowed. Miserable doesn’t describe it. They were young though and adjusted as best they could. There was no where to escape anyhow.

At the beginning of the voyage the Nisei were restricted their cabins for fear that there might be trouble with the soldiers and the crew. Later it was thought that perhaps getting to know them was the better course of action. Everyone was notified of the decision and everyone was allowed to mingle. During the day the decks were completely covered by soldiers, mainly replacements for the 32nd, Red Arrow, Wisconsin National Guard, the 37th, Buckeye Division, Ohio National Guard, the 41st, The Sunshine Division from the states in the Pacific Northwest and the 23rd or Americal Division. All of them involved by this time in heavy fighting in New Guinea.

Each day the soldiers practiced with the bayonet, cleaned their rifles, sharpened knives and convinced themselves how tough they were. They averaged just about twenty years and their hubris came from being young and having almost no exposure to life outside the mostly rural areas they came from. Many had never seen a Japanese in their lives.

For the Nisei the release from their cabins turned out to be a mostly positive thing. As they got to know each other they found out how much alike they really were. A farm boy is a farm boy no matter his ancestry. In the trek north to Japan the soldiers would come to value very highly their new Nisei friends who would share all the hardships of combat with them and whose translation skills would save hundreds of lives.

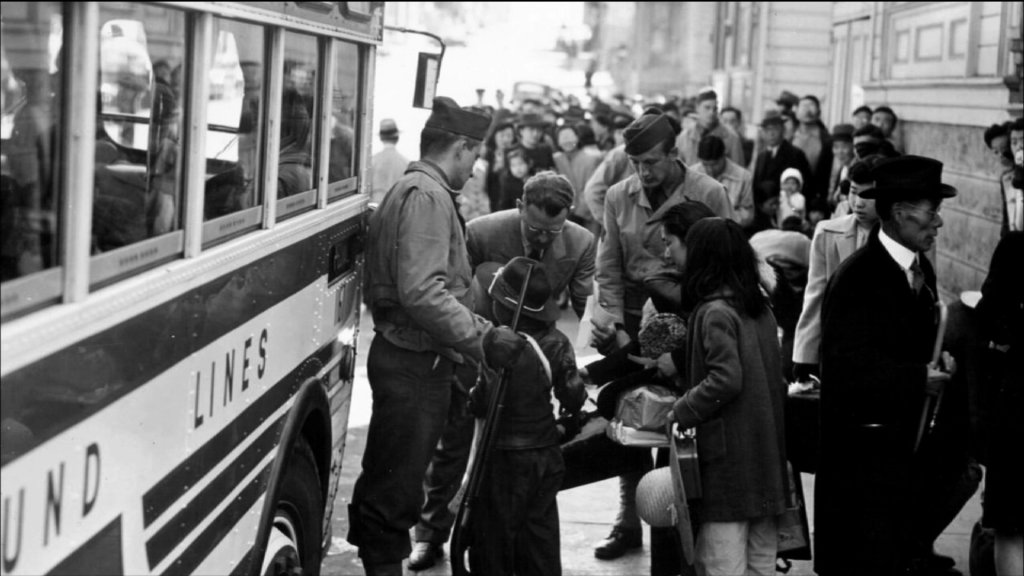

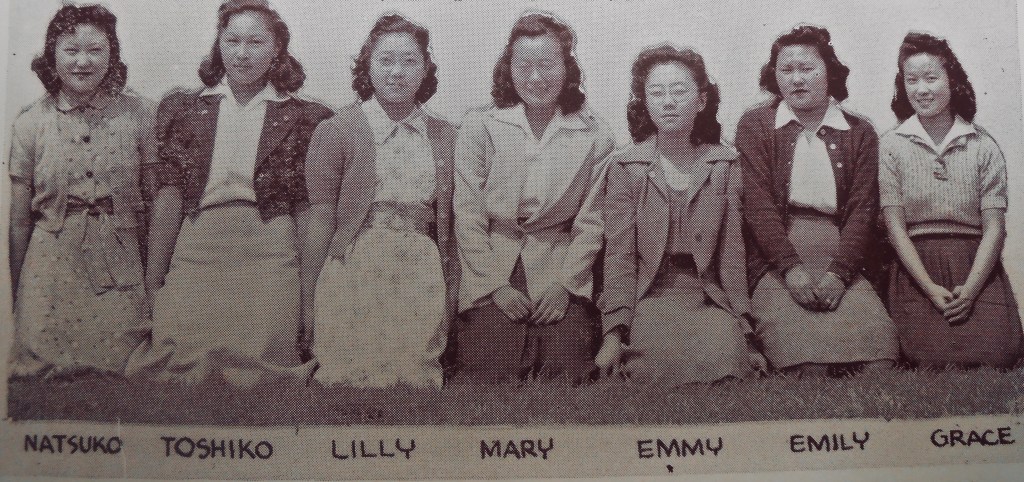

Still they talked about the problems communicating directly with the enemy, in the language of one’s parents. The idea was incredibly fraught with personal feelings especially for the Kibei who had the greatest exposure with Japan proper. To some it presented difficult questions about identity and heritage. For many Japanese Americans, it was difficult to reconcile using the Japanese language for American victory when their dog tags bore the address of the camp back home in the United States where your parents were incarcerated. In many cases, the translators had had no opportunity to even visit families and the addresses that listed Manzanar or Tule Lake California, Gila River and Poston Arizona, Amache Colorado or Rowher, Arkansas must have caused pain every time they looked at them.

So here they were, a small contingent of specialized troops traveling with thousands of Caucasians whose suspicions and hatred was dangerous to them, whose families were locked behind barbed wire in concentration camps and whose President had written about his decision to intern Japanese Americans was consistent with Roosevelt’s long-time racial views. During the 1920s, for example, he had written articles in the Macon Telegraph opposing white-Japanese intermarriage for fostering “the mingling of Asiatic blood with European or American blood” and praising California’s ban on land ownership by the first-generation Japanese. In 1936, while president, he privately wrote that, regarding contacts between Japanese sailors and the local Japanese American population in the event of war, “every Japanese citizen or non-citizen on the Island of Oahu or in California who meets these Japanese ships or has any connection with their officers or men should be secretly but definitely identified and his or her name placed on a special list of those who would be the first to be placed in a concentration camp.”

Imagine the confusion on the one hand and the desire to fight for a country that didn’t want you on the other. Like my father said when questioned about the issue, “You cannot understand it because you haven’t lived it.” And of course thats true as far as it goes. Today, we have far more documentation of those events than was possible during the war when the public was restricted to almost none.

Steaming day and night the group of ships headed southwest, zig zagging to reduce the chance of torpedo attack and on the seventh morning those on deck sighted Diamond Head. A soldier from Ohio turned to the Nisei next to him who was from Kaimuki, Oahu and asked if that was what Japan looked like to him, the Nisei replied “It looks like home to me.” As Bob Toyoda told the story years later he laughed at the confusion on the face of the Ohio boy who was going to war against a country he knew nothing about, not even where it was.

SS Mariposa, USAT enroute to Auckland New Zealand, July, 1943. Australian War Memorial photo****

Much to the dismay of the passengers, especially the translators from Hawai’i, the escorts turned to starboard and headed for Pearl Harbor but the Mariposa turned to port and picked up a compass bearing of 150 degrees south-southeast (SSE). It was going to be another long, long three weeks aboard.

Dona page 6

From the promenade deck, Hilo and the other translators could just make out the smudge on the horizon that they knew by now was Auckland, New Zealand. Six thousand seven hundred miles and a month at sea and no one aboard was any more anxious to get to shore than they were.

*General George Stoneman was a cavalry general in Grant’s army. He is mentioned in the song “The night they drove old Dixie down.” His name would have been well known to southern boys.

**Todays home of The San Francisco Maritime Museum and known as the Hyde Street Pier.

***The old Dollar Line owned by Robert Dollar has through mergers become the American President Line.

****This very likely the ship Hilo traveled on.

Cover Photo: SS Lurline in war paint leaving San Francisco for the southwest Pacific.

Michael Shannon is a writer from Arroyo Grande California.