Page 14

The Last Battle

By Michael Shannon

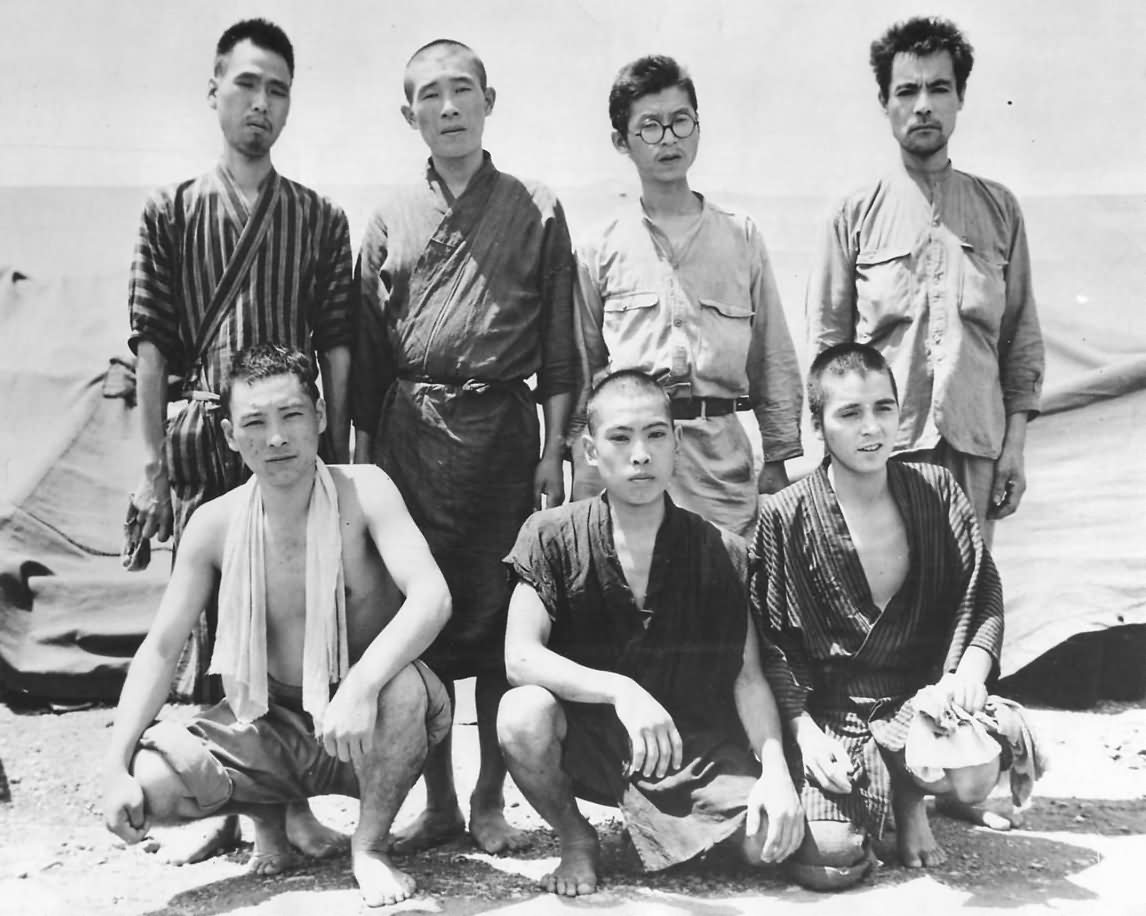

“The God of Death has come.” Shouted by a Japanese Imperial Naval Marine* upon seeing Marines landings on Betio, forever enshrined in the notes taken in interviews by MIS translators during the battle for Tarawa.

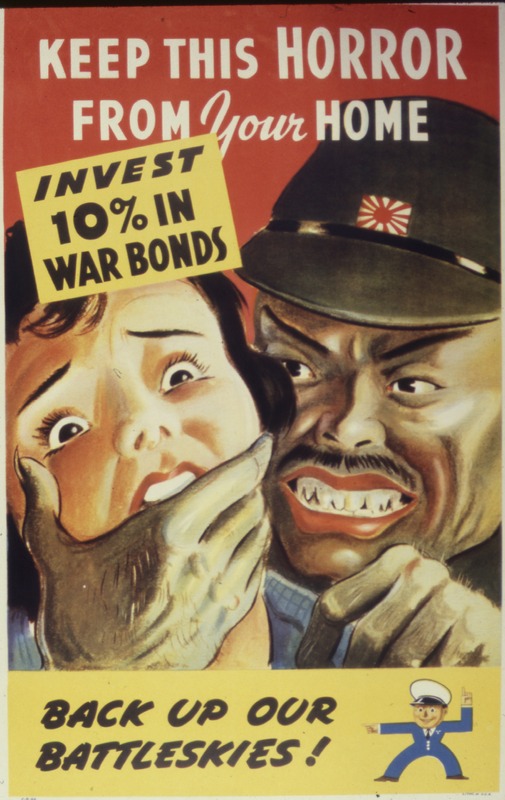

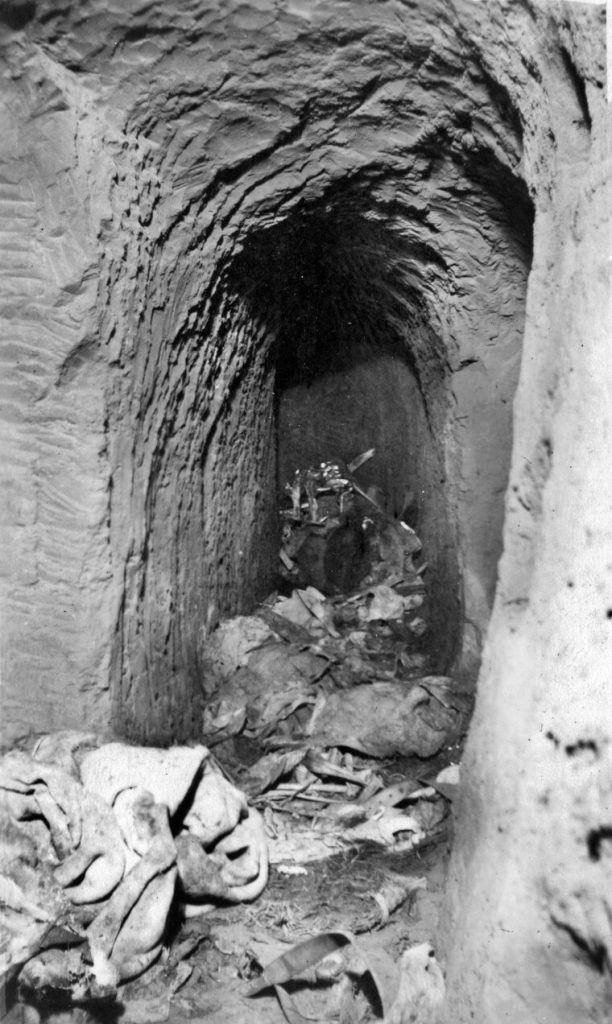

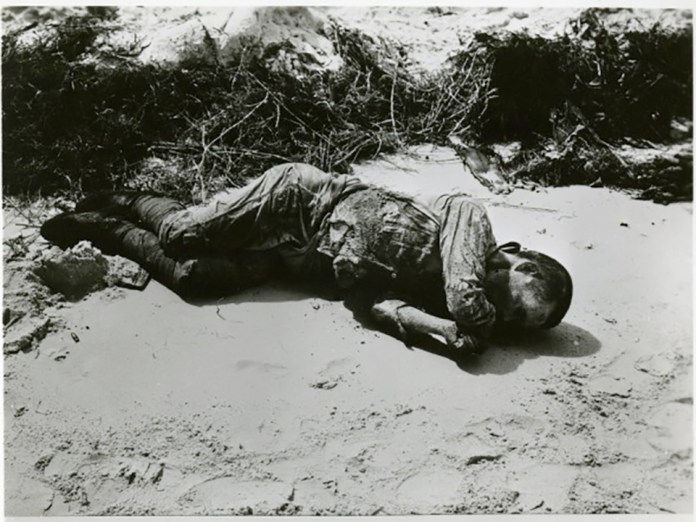

The filth, the crawling over sharp coral, running crouched, hunched over with every muscle in the body nearly rigid with fear, the noise which never stopped, artillery, flamethrowers, grenades and the constant pop of gunfire. Battleship shells weighing a ton, Destroyers nearly run up on the beach duking it out with gun emplacements at point blank range. A miss is a miss but the M-1 round still can kill at 6,500 yards, over 3.5 miles. The Japanese Arisaka type 99 rifle could kill at 3,700 hundred yards. No place on the island could be safe for the soldier. The air is full of them. There was no place safe. No one could think or conceive of any other universe. The Battle of Okinawa (Operation Iceberg) was the final major land battle of World War II, lasting 82 days from April 1 to June 22, 1945. It was a brutal, large-scale engagement where U.S. and Allied forces fought Japanese troops on the island of Okinawa, the last step before a potential invasion of Japan. The battle was exceptionally bloody, resulting in massive casualties for both sides, including a significant loss of civilian life among the Okinawan people, and heavily influenced the U.S. decision to use atomic weapons on Japan.

Soldiers are so young. Is it impossible that they should be able to process the situation they are in? When they awaken at the bottom of their waterlogged foxholes after dreams of home they understood there was no escape.

Witness this Marine Ambulance driver’s letter home written about half way through the invasion. He would celebrate his 19th birthday on Okinawa.

Dear Folks. I know you have been worried about me but as you see I’m still very much O K. I’ve had a few close calls but that can be expected on this Rock. They say in the stateside news that this island is secure but, but they still have eight more miles to go so you can figure that out. We are three miles back from the front licking our wounds now and waiting for I don’t know what. Maybe we go back and maybe we don’t. I guess I’ve seen most of this island so far—enough anyway.

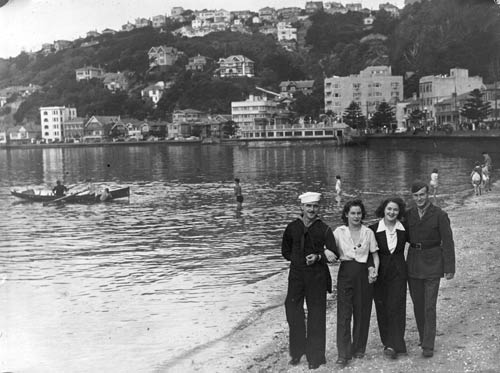

Private John Brewster Loomis USMC, Headquarters company, 1st Battalion, 1st Regiment, 1st Marine Division. MOS 245, Truck Operator. Just before shipping out to the Pacific, 1944.

Shuri Castle was a rich joint and Naha used to be quite a town. I am sitting in Jap truck now that we picked up in our travels. It is something like a ton and a half and something like a Chevrolet but right hand drive. I’m a little thinner but feel alright. (He entered the Marines at 5′ 11″ and 160 lbs.) Instead of “Golden Gate in ’48, it’s from Hell to Heaven in ’47. Old Snowball, a friend, is still alright as far as I know. We sure took a beating but took our objective.

Dad I’m sorry I couldn’t write on your birthday but Happy Fathers day and Fourth of July.

The weather is better now, cold at night. Last night was the first time I got to take off my shoes when I hit the sack. They brought us a little better chow for a while. Boy! Am I tired of C-Rations. My old ambulance is still running but it doesn’t look the same-no windshield. bumpers, paint, top or sides-just one seat and the stretcher racks.

I had my picture taken the other day by Division. I don’t know if it will get in the papers or not. I sure didn’t look like much that day.

Well, folks, I’ll write when I can and I hope from now on that will be very often. Much Love John.**

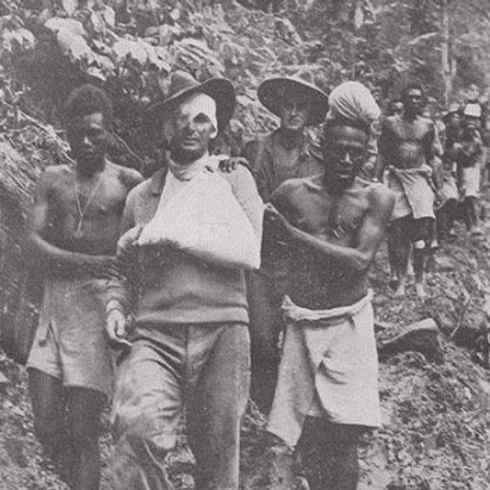

Modified by Holden an Australian body building company, this is the Jeep type ambulance John Loomis drove on Okinawa. The Marine Corps used this much more, go anywhere ambulance instead of the big GM trucks used in Europe. The rugged terrain and mud sloppy roads couldn’t be navigated by trucks and Sherman Tanks were sometimes used as tow trucks if they didn’t sink in the mud holes themselves. Almost everything was hand carried by exhausted Marines themselves.

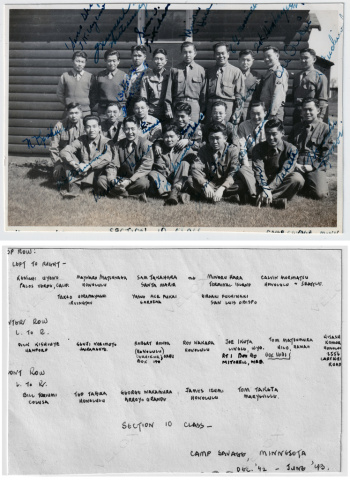

As the battle for Okinawa came to a close, many of the Nisei translators were ordered off the island. The almost complete annihilation of the defenders meant there was little to do. In preparation for the invasion of Japan there was a mountain of captured documents to be gone through and they were needed back at headquarters.

The Lieutenant gathered the Nisei translators in a shell hole covered with a tent fly then read the names of those who would take one of the LCIs out to the attack transport (APA-139, the USS Broadwater) for transport back to Manila for further orders. Hilo and his team were leaving the island.

MacArthurs headquarters were now in the ruins of Manila. After unloading at Cavite Naval base in Manila bay, the MIS boys were trucked to the city and reported for duty.

Hilo and his team were issued new orders and upon pulling them open with a mixture of excitement and dread inherent in the action were delighted and almost giddy with the news that they were to report to Subic Bay for immediate transport to Naval base Long Beach, California to begin a 30 day leave. They were being sent home to rest before the invasion of Japan.

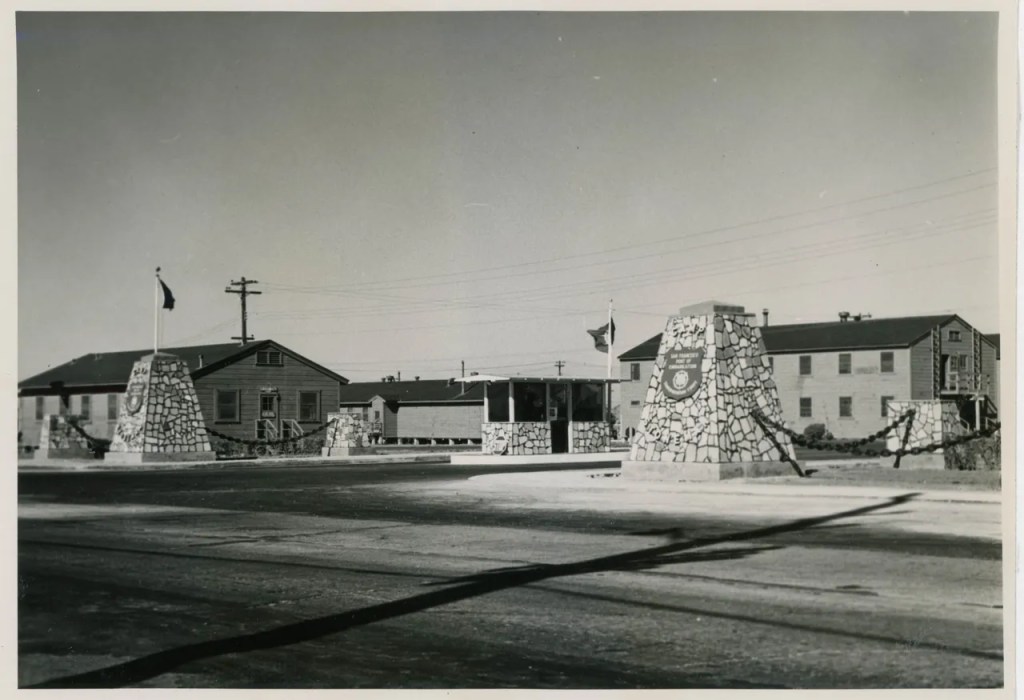

USS Broadwater APA-139 and USS Bellepheron ARL-31, a landing craft repair ship at anchor, San Francisco 1944

They were going to be transported by one on the Navy’s APAs or Attack Transports such as the USS Broadwater APA-139. The APAs*** were the real workhorses of the Navy. They were designed and built on Liberty and Victory ship hulls for the purpose of transporting men and supplies. With their boats they were able to house, feed and land an entire marine battalion of fifteen hundred men. Anchored just offshore, in harms way, they would swing out the landing craft, load the Marines and their equipment and then the Cox’ns would drive them into the landing beaches. When they had unloaded they would wait to receive the wounded and other men pulled off the line and return them to base. Equipped as emergency hospital ships they would offload casualties to the larger dedicated hospital ships waiting outside the arc of Japanese artillery fire and Kamikaze air strikes.

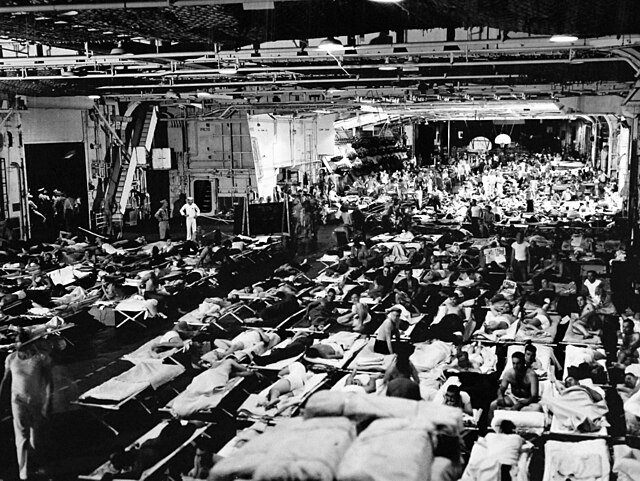

An Aircraft carriers hanger deck loaded with casualties from Okinawa, April 1945. War Department Photo.

The Navy operated over three hundred of these ship along with freighters of the Liberty and Victory types, over fifty oilers, and a myriad of specialty support ships. This allowed the Navy, Marines, and the US Army to operate efficiently more than 7,000 miles across the Pacific Ocean where there was little infrastructure to support operations. The logistics of the operations are literally mind boggling.

The APA’s were to serve a special purpose beginning in the waning weeks of July and August 1945. In the service any action needs have a name to identify it. Most, such as Okinawa which was dubbed “Iceberg” and the invasion of Guadalcanal “Operation Watchtower” general have no meaning other than to confuse the enemy but the name for the last major movement of men was oddly prescient. Operation “Magic Carpet” would return veterans of the Pacific home. By August the allies had just over 23 million troops and support service men in the western Pacific. The Aussies, New Zealanders, British, French, Dutch and the Mexican Air Force were all going home. Magic Carpet would be the largest mass transport of men and women ever attempted. Every ship type was going to be utilized for transport.

On July 25th Hilo Fuchiwaki and his team boarded an APA in Subic bay. The boys must have leaned over the ships rail and watched the sailors on the dock cast of their lines and felt the ship begin to vibrate as she backed into the stream and headed for home.

Dear Dona Page 15 is next.

Cover Photo: Holden Jeep ambulance. Missing one fender, other one dented. Shrapnel hole in hood, broken windshield. The exhaust pipe is extended to get it out of the mud. No paint and tow strap wrapped around the bumper. Hard used.

*Rikusentai, Imperial Japanese Naval Marine Infantry.

**The letter must have been written after the the capture of the Katchin peninsula by the 1st Marines. The battle for the island still had about ten weeks of combat left. He was, after a short rest to participate in some of the most brutal fighting ever seen in WWII. Private Loomis earned the Bronze Star for his actions on Okinawa.

***The book “Away All Boats” which was made into a movie of the same name based on the 1953 novel by Kenneth M. Dodson (1907–1999), who served on the USS Pierce (APA-50) in World War II and used his experiences there as a guide for his novel. It is considered a classic in naval literature.

Michael Shannon is a writer and lives in Arroyo Grande, California.