Its a mans life you hold in your hands.

My dad’s family were farmers in Ireland. That’s what they knew. Like all immigrants they came to America for opportunity. They came because laws in Ireland held them captive in a system of government that placed no value on small farmers. Just twenty years before my great-grandfather was born, it was still illegal to educate Irish children. An Irishman could not vote nor own land unless he was of the ruling class. The Potato Famines of the early 1800’s began the drive for immigration in which 1.7 million Irish came to America between 1840 and 1860. This flood from Ireland continued, unabated for 50 years. Today there are about 36 million americans of primarily Irish descent. Only about 6.4 million Irish still reside in Ireland.

An Irish crofter, as farmers were known, held property in trust from the large landholders who actually owned it. The average Irish small farm was roughly one eighth of an acre. Can you imagine living and growing subsistance crops on a piece of ground only 5,400 feet square? Thats about 75 by 75 feet! The United States, stretching for over three thousand miles to the west was an almost unimaginable thing. It was near impossible to imagine how large it was. Even today people of this country cannot imagine it’s size.

My great-grandparents, the Greys, Samuel and Jenny were from Ballyrobert Doagh, a crossroads on the river Doagh in County Antrim, Ireland. They came to America on their honeymoon in 1881. The sailed on the packet ship State of Alabama which ran a circular route from Glasgow, Scotland to Belfast, Dublin and Cork. Once loaded, it made passage across the north Atlantic. Those trips took as much as 12 weeks to make. The ships themselves were combination steam and sail which was somewhat of an improvement over the so called “Coffin Ships” that made the trip some thirty years earlier. During the Irish Diaspora as much as half the steerage passengers might die enroute. All of the major destination cities in the United States and Canada featured mass burial grounds filled with the hopeful.

They boarded the States Line ship “SS State of Alabama” in Belfast and arrived in New York on the 6th of June, 1881 after a quick summertime passage of just 18 days. Sam and Jenny made it to New York harbor where immigrants were held in quarantine on board until cleared for landing. Once cleared they at disembarked Castle Gardens on the lower end of Manhattan Island.

Sam Grey worked all kinds of jobs as he made his way west to California, arriving finally in San Leandro and then down to the the Salinas valley where he grazed sheep. His wife Jenny had relatives living in the Oso Flaco area of California and eventually they came here. They rented some land along Division Road and he grew potatoes of all things. Ironic, but a decent profit. My grandmother was born in that little house, the second of there eventual seven living children.

That child grew up to be my dads mother, one of a family of farmers and dairymen that included McBanes, Mcguires, McKeens, Moores, Greys and Shannons. Today politicians refer to this as chain migration but they are fools. Family following family has always been the rule, always will be. The Irish didn’t ask for any hand out; they wanted a way out and they were willing to work to get it.

Agricultural servitude is term applied to those that work the ground for pay, usually meager. It applies not to just the field laborer but the owners too. My father, the grandson of Samuel Gray was one of these men. He was raised on a dairy farm as they used to be called because not only the milk cows were raised there but the oats to feed them. My grandparents also raised beans, peas, tomatoes, hogs, turkeys and for comic relief, many, many dogs, some who stories are legend in our family. No goats though, Grandma said that only shanty Irish raised Goats, plus the church taught that animals with cloven hooves were unclean and satanic. Thats the way she thought and thats the way it was.

Annie Shannon, my grandmother about 1925. She is 40. Hillcrest Dairy, Arroyo Grande, CA. Family photo ©

Dairies are the chains that bind the farmer to the ground. Cows are milked two or three time a day and the dairyman follows the old rule, “Dark to Dark,” when he works. Little boys like my dad and uncle learned the lesson early for they had to begin pulling their weight as soon as they were big enough. Kid chores like feeding chickens and collecting eggs and as they grew, the load became heavier. As teens they rose before dawn, went up to the barn to help with the milking and then the bottling and cleaning. Off to school for the middle of the day, they returned in the afternoon for the evening milking. Every day seven days a week, twelve months of the year including all holidays. The cows took no time off and neither did the customers.

When I was little my dad was farming in the upper Arroyo Grande Valley. He grew what are known as row crops. Vegetables like celery, broccoli, lettuce, tomatoes and string beans were what he raised.

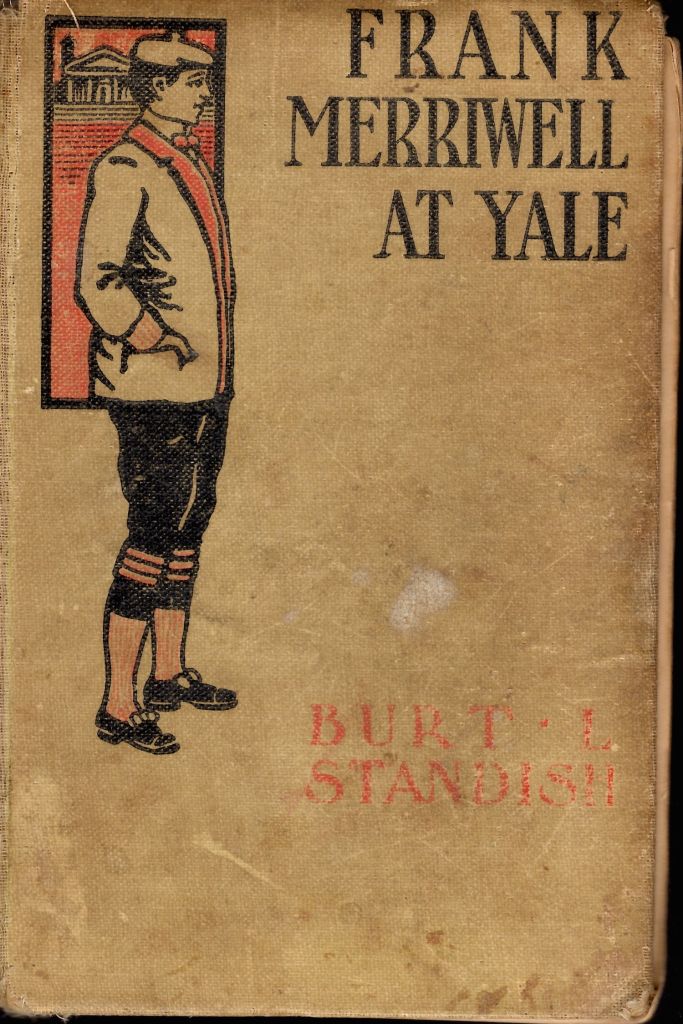

Unusual for a farmer of that time, Dad was a 1934 graduate of California Berkeley. He once told us that the main reason he went to college was, one, my grandmother had graduated Cal in 1908 and she wanted him to go, two, his father wanted him to study the law but most of all he went because he’d read Frank Merriwell at Yale, a pulp fiction book from the early twentieth century about Frank’s grand adventures at Yale. He and my uncle Jackie used to walk up to the old Union hall, fondly known as the “Rat Race”, which was at the corner of Mason and Branch streets. On Saturday afternoon they’d plunk down a nickel and sit down in one of the wooden folding chairs or the eclectic collection of press back chairs salvaged from somebodies kitchen and watch what were still called Flickers because they did,flicker Harold Lloyd, Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, Fatty Arbuckle, Mabel Normand and the madcap cops from the Mack Sennet studios made kids laugh. The “freshman” starring Harold Lloyd or “College” from Buster Keaton told an age old story. They had storylines that led Dad to visualize college as a place where Nerdy grinds were picked on by strapping young athletes, ignored by pretty girls but somehow managed to save the day by winning the big game on the very last play. The pulp novel, “One Minute to Play”, which we still have features a football hero forbidden to play in college by his pastor father. A hundred years have passed since Dad and uncle Jackie sat on the edge of their chairs in that drafty old dance hall but the plot remains the same. Those things, he said were his primary reason. They were a good as any. And he did have a great time to boot.

He came home to Arroyo Grande after graduation. It was the middle of the great depression when work and money were scarce. Businesses were barely hanging on and opportunities were few and far between. Choices had to be made.

Farming and ranching were familiar things to him though he later said that he didn’t want to be a dairyman because the work was so relentless. He chose row crops instead. Which, when you think of it is only slightly better. It’s still six and one half days a week, dawn to dusk though it slows in the winter some. Fewer crops but more adobe mud, there is your trade off.

Slogging your way down the rows dressed in oilskins holding the slippery handle of your 12″ Broccoli knife, slippery with mud, hands with no gloves in the rain, cold at 7am, still nearly dark. Left hand grasping the stalk below the leaves, a blind slice, the cut and throwing the severed head through the air and into the cart being pulled behind a wheel tractor. The driver and the tractor set the pace and it’s relentless. Head down, sucking mud, mind numb, no time to think, just do the job. For minimum wage. They tell themselves that there is no one who will do the work and some pride is taken in that. What else can you do?

It’s like the old saying, a boy tells his father after his first day of bucking hay, “I sure hope I don’t have to do this for the rest of my life.” Before he knows it, sixty years on he’s still doing it. Life is like that.

There is just something about the orderly manner in which crops are grown. All the preparation and finally after walking through the planted but still barren fields looking for that tiny two leaf sprout which ever and ever again promises that life will renew. That is the true farmers delight.

My father never bought a new truck in his life. He though of it as showing off. He didn’t glad hand or seek out the company of other farm men and contractors, no breakfast meetings at Goldies with the three percenters and the reps from NH-3 or the seed salesman. It was wasted time. If he needed them they were just a phone call away. Though all of that is a tried and true way of doing business he considered it a waste of time.

Time was better spent managing his crops for he was extremely proud of produce. As a boy I worked in his packing sheds, wherever they might be. He had more than one ranch. He would take me out to the Berros ranch or up to the one on the Mesa and I would pack vegetables. One of the keys to understanding my father was to know that he would never cheat you; ever. Every vegetable is those boxes was to be perfect. The prize tomato on the top was exactly like the one on the bottom. In a flat of Chinese peas which held hundreds of pods, every one had better be perfect. It’s what he expected of you and its what he produced for the buyers. In that way he taught me to be meticulous about any job I did. As a 13 year old I didn’t get it, it made the job slow and monotonous but somehow the lesson stuck. I’m not sure if he saw it as a lesson but It’s what he expected of himself and it was the same for me. I thank him for that.

I remember riding with him in the pickup and dad pointing out the farmers who couldn’t plow a straight furrow or ran their irrigation water onto their neighbors, those things mattered to him. It’s funny because our tractors lived outside and were dirty and rusty and in the slowness of winter the weeds grew up around them and they looked abandoned. He didn’t care about that, they just had to run. Their only purpose was to serve the crops. Crops, perfect, tractors, not so much.

My dad was thirty three when I was born. When I was a pea packer he was in his middle to late forties, his prime years and had been a farmer for a quarter of a century. By the time I graduated high school he’d been at it for thirty years. He’d seen a lot of changes in farming in that time but was about to face the death knell of the family far, consolidation. After the wars population surge there were many more mouths to feed in America and the pressure on the smaller family farms to remain profitable increased.

Daddy and me, first birthday 1946. Family Photo

The Vegetable packing houses which contracted with the individual growers and the advent of huge grocery chains increased demand for production. For example my dad grew celery on contract for a local packing house which sold celery to grocery chains all over the country. No longer did the little local trucking company haul your produce up to the San Francisco markets or down to Los Angeles. Your celery might be going by train to New York or Chicago and in bulk, orders made up of the crop from a dozen small farms. Some farmers, more businessmen than growers formed co-ops or bought out the individual family farms. This allowed the large grower to make demands of the brokers and introduced economies of scale to lower their production costs. This worked against the small farms like my dad, the Betitas, Kawaguchi’s, Cecchetti’s, the Silva brothers and My great uncle John Grey. Their was no more growing land available and they began to be squeezed out of the markets. It wasn’t as if there produce was inferior but when it came to essential services they needed they were forced to wait in line. What this meant is that vegetable market prices which fluctuate literally hourly are a target everyone is shooting for. A delay in harvesting and shipping can be very costly and when a large grower demands that his celery be cut and shipped on the day or days your crop is scheduled for it can cost you your profit. This in our little valley. Imagine Ralphs demand that a vegetable broker not only meet what they are willing to pay but that the broker must supply every Ralphs in California or even the nation. No family farm can do that and thats why they have gone the way of the Dodo bird.

In the nineteen sixties you could count down from the site of Santa Manuela school to the dunes by family name. Biddle, Grieb, Donovan, Talley, Antonio, Evenson, Fernamburg, Cecchetti, Ikeda, Kawaguchi, Shannon, Sullivan, Coehlo, Berguia, Gularte, Waller, Reyes, Betita, De Leon, Dixon, Fukuhara, Marshalek, Fuchiwaki, Saruwatari, Taylor, Kagawa, Kawaoka, Matsumoto, Nakamura, the Obyashi brothers, Sakamoto, Sato, Kobara, Sonbonmatsu, Hiyashi and Okui. There were Phelans, Donovans and Elmer Runels too.

The Betita Boys, 1960’s running string for pole beans. Used by permission

See, the thing is you gotta be in it to win it. Farming takes a gamblers approach. Farmers know that farming is an extreme investment. Finished crops return a very small percentage on the money you put into them. Equipment is expensive if you look at the cost of just an individual item like a Caterpillar. What few think about is the add ons, the Disc, Harrow, plow and the roller. There is gasoline and diesel, oils and grease to be paid for. You have to have a tank to store the fuel. Unless you have kids of an age a driver must be paid. Seed, fertilizer, pesticides and the cost of running the water pump. Who moves the irrigation pipe? How about the crop duster?

Where is the labor to be had. That’s rough and dirty work usually done by folks with few other options which in itself brings problems of attendance and theft. Drinking before, during and after the job. This is the kind of work done by the desperate. People so poor that they will steal lettuce knives, the baskets used to pick vegetables, shovels or even your shirt if you leave it lying about. For us this problem was abated with the introduction of the Bracero program which brought young Mexican men into the country to replace the field workers who were in the military. After the war the soldiers didn’t come back so the immigrant program was continued. Until 1964 this program supplied nearly five million workers to farmers in 24 states.

We, and most of my friends grew up with these guys which, I think gave most of us an appreciation for different cultures. To leave your home and come across the border to work for people who didn’t speak your language and had no interest in your culture was a form of bravery that I understood.

Nonetheless the small farmers struggled and when we had an early, very hard freeze which killed nearly every crop in the valley it spelled the end for many. Bank loans were not forthcoming, there was no crop insurance, no Federal subsidies and in most cases no cash on hand to pay your vendors. Bankruptcy was an option of course but men like my father and especially my father would never admit total defeat. The bills were piling up and some companies, even ones run by close friends were demanding payment. I can’t imagine how he did it but he just put his head down and paid what he could. It took years to crawl out from under the debt. He forbid my mother who worked to pay off one dime, it was his debt. The big freeze was only one disaster. Down in Berros the deer were bold enough to come into the tomato fields and eat the fruit in broad daylight costing thousands of dollars. He got a permit from the county to shoot them but you had to dress them out and deliver them to the county’s general hospital which became a huge job in itself. He had to give it up. I was a senior in high school then. One year storm winds blew down acres and acres of pole peas, the mainstay of his operation. You could look out our kitchen window and see the field with the ripe, producing vine lying flat on the ground. One winter there had been so much rain that the tractors could not get into the fields to harvest the celery. Crop loss, natural disaster and the dominance of the larger operations was like one step forward and two back.

I can’t imagine the courage it took to move ahead but in 1980 he had, had enough. He and my uncle sold my grandmothers cattle ranch and he used the money to retire. In those days it was rare for a farmer to have a pension and most depended on Social Security to survive. So he took some of the money and bought a lot in town and I built them a retirement home. He always said he wanted it there so he could see the old home ranch where he was raised. Just like the home I grew up in where you could look out of the kitchen window and see the crops grow and the neighbors pass by the new house had that big picture window next to the kitchen table where he could sip his coffee and see where his life began.

Mom and Dad with their three sons in 1986. New house. Family Photo

So they left the ranch near the four corners and never looked back, his last and favorite dog moved to the junkyard on Sheridan Road up on the mesa and they settled down in the new home at the corner of Pilgrim and Orchard streets. Mom and Dad lived quietly there, she passed away first and he followed a few years later. He missed her because he loved her so and his last years were lonely and like many old folks slightly bitter for what was lost. Weighed on the scale of life I believe there isn’t enough Gold on earth to level his worth as a man; old fashioned in his beliefs but a superb father which is what counts with me. It’s funny but as a little boy I called him Daddy which I outgrew as children do but at the end thats what he was, my Daddy.

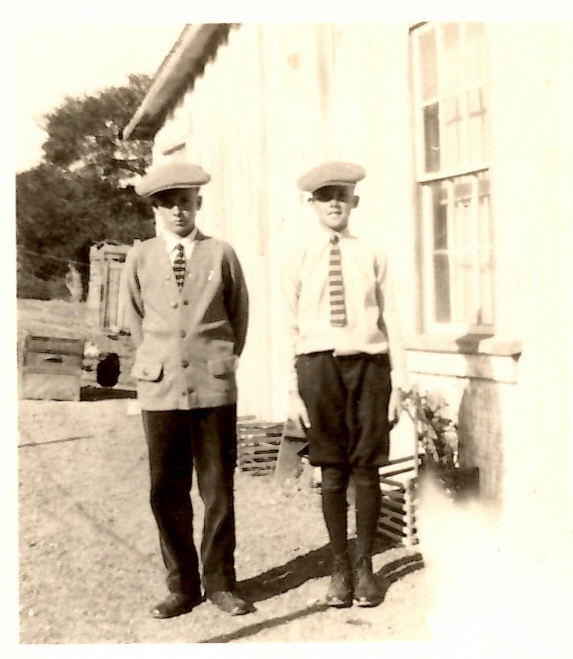

- Cover Photo: Jackie and George Shannon on the dairy. 1922. Family Photo

Michael Shannon is a writer and a son. He writes so his own children will know their history and who they are.

Beautiful history. Brought tears when your parents sold. I was never a farmer, but worked for the past 50 years to keep the family property. My daughter and her husband moved in with me 5 years ago and she has been ‘gungho’ about raising chickens after the introduction of COVID. BitchinChicken is her Facebook site. Enjoy your stories. Thanks.

LikeLike