By Michael Shannon

Kids that grow up on farms and ranches are like the pups. They are always on the lookout for Dad coming out of the house and headed for the pickup truck. They know that he will lead them towards adventure. It doesn’t matter what that is, it’s just the opportunity to go somewhere with him. The dogs think the same way. The front seat of the old truck with it’s torn upholstery, and sagging springs, even the broken one which lies in wait like a rattlesnake has room for all. Over on dad’s side the viper, it’s one fang hiding just below the tattered hole where his butt slides when he’s getting out, he misses it most of the time but once he’s worn those Levis long enough they will bear the mark of the just missed.

Bumping down the farm roads, still rutted from last winter kids hold on swaying left or right depending on how many holes and ridges dad can miss.

Pride of place rules apply, the youngest sitting next to dad resting his towhead firmly against pop’s Pendelton’s sleeve, the middle brown haired one with the cowlick, squished in the middle and the oldest owning the door. He has arms long enough to reach outside and push down the chromed door handle because the inside has gone missing. My dad never focused on trivial things like hunting up an Allen wrench and digging through the cluttered tool box in the back in the remote possibility that the missing handle might be there. He used the drivers door.

Some days we drove past the tin sided pump house, the very big electric pump humming away inside pulling groundwater up and forcing it through the buried 8” pipe that ran along the uphill side of the fields. At regular intervals stubs of pipe, each one with a threaded caps stood sentinel like so many soldiers waiting for orders.

In the nineteen fifties most irrigation was fed by ditches plowed at one end of the field. Small stand pipes screwed into the risers delivered water under pressure to fill the ditch. From the ditch, siphon pipes drawing from the main ditch delivered the water to the rows along which grew the plants. Tomatoes, Celery, Lettuce, and Broccoli were all irrigated this way.

My dad with his shovel on his shoulder patrolled the dozens of rows to make sure that each one was irrigated evenly. Controlling the water by sliding the little gates on the siphons to slow or hasten the water on its way. Back and forth, back and forth like a soldier on duty. He slogged through the muddy rows building small temporary dams to slow progress, the goal being to make sure the water reached the end of the quarter mile long rows at the same time.

Simple looking to the uneducated observer the practice dates far back into the mists of time. The Hanging Gardens of Babylon were watered this way. The ancient Sumerians funneled water from the Tigris Euphrates river system to grow grain and fruit trees in the Fertile Crescent. Canals were built to bring the water down from the Zagros mountains in present day Iran to supply the cities of Mesopotamia more than twelve thousand years ago. The technology has not changed to this day. It’s simple but elegant in the way that successful technologies are. You can still see row irrigation on farms and ranches all over California. No doubt little Babylonian boys and girls played in the ditches just the way we did.

Simple but complex in the doing. The water had to be channeled in a way the provided maximum saturation of the soil for the plant to thrive. Our farm had at least four types of soil mix and each one dictated how the irrigator worked. Too dry and hot weather could kill the delicate plant before it could be irrigated again, too wet and the roots would drown and kill the plant. Water was applied differently for crops which had just been fertilized. Consider the age of the plant and it’s harvest time which the farmer knew to the day. Tractors are heavy and soft wet soil will compress and crush a plants roots. So, it’s not just a man out standing in the field, it’s a skill.

There are certain mores involved, at least for my dad. Plow a straight furrow, water highlights a crooked line and he was always checking the neighbors to see if theirs were arrow like. A small thing I suppose but it is part of what I learned from him which was how important it was to do a job well no matter its importance.

Running the water across the road onto your neighbors field was a major faux pas and dad took pride in never letting that happen. Our uphill neighbor’s irrigator, Roque ran his water onto us all the time. Dad would privately grind his teeth, muttering under his breath about lazy men but when he talked to Roque about it Roque would laugh out loud and tell my dad, “I never do anymore, Mister George” and laugh again. Next day he would do it again. My father never said much to him because he was so irrepressibly happy that it was impossible to take any serious offense. It’s difficult to fault a man that laughs.

We, on the other hand did our best to get a muddy as possible. Because we were too little to handle a shovel we used natures backhoes, our hands. The main ditch was about two feet wide and a foot or so deep, enough to drown a child I guess, but no one, us kids or my father seemed to be the least bit concerned. On the uphill side we used our hands to dig canals so we could make the water run where we wanted it. The canals went nowhere and the only purpose was to get the water to run freely. This was our first lesson in understanding hydraulics. Each little ditch had to be just off level in order to make the water move in whatever direction we wanted it to go.

Since our fields were a mix of alluvial soil and heavy adobe they made the worlds finest mud. You could add enough water to make it slurry which was really great for throwing at the pickup because it stuck like glue. A little bit dryer and it made great little adobe buildings to go alongside the ditches. Certain combinations were terrific for slicking down a brothers hair.

There were plenty of stems on the ground leftover from last seasons crops that could be woven into rafts and not far away, an old abandoned Diamond Rio flatbed truck draped with blackberry vines. The leaves could float GI Joe on his way across the Rhine River. The occasional Sycamore leaf blown up from the creek served as major people movers. Sadly many a GI Joe lost his little plastic life by being swept away on Tidal waves never to be seen again. Leaves have no handrails and though Joe can float he cannot under any circumstance swim. Pretty sure cultivators are still occasionally turning up their tiny corpses while working those fields. GI Joes may perish but their little bodies never decompose.

When we were just a little older we would hunt through the packing shed and corn crib looking for small pieces of left over wood and with a little ingenuity, a nail or two and a ball peen hammer make them into many kinds of ships and boats. Nails driven into the sides stuck out just like battleship cannon, or so the six year old mind imagined

Dozens of ships in the Japanese fleet were lost to a barrage of dirt clods fired from behind the pickup. No invasion of the Broccoli ever succeeded. As children of the second world war we understood the importance of fleet actions. Clods when lofted as high as we could toss them made very satisfying splashes. We didn’t need a game bought at the dime store we had endless resources in which to make our own games. No one I can remember ever told us the truth of things to crush our imaginations. That would come soon enough.

My little brother would crawl up the running board and lay on the front seat and nap when he got tired. Jerry and I kept it up until it was time to head back to the house. Dad’s boots and Levis would be soaked with mud and water to the knees and we could of passed for Mudmen ourselves. We had accomplished much though, held off an invasion, built hydraulic systems and thoroughly enjoyed ourselves. When you grew big enough you might get the privilege of riding the running boards back to the pump house, going inside through the tin door with its screech owl hinges and using both thumbs push the big off button on the pump.Stay a moment as the big electic pump wound its way down from its jet engine howl to silence. Little things like that mean a great deal to little kids. They understand that you earn responsibility.

Back at the house it was strip, leave the clothes on the back porch floor and run and get in the big oversize porcelain bathtub for a good scrubbing. Scrub brush on the bottom of the feet, rolled up washcloth pushed as far into the ear as mom could make it go and then a big fluffy towel, try not to slip on the wet linoleum floor, “Careful, careful,” mom cautioned over and over again. Trying to hold onto three slippery wet boys at the same time.

Funny thing I remember, Mom and Dad never scolded us for being dirty, they always seemed to be as delighted as we were.

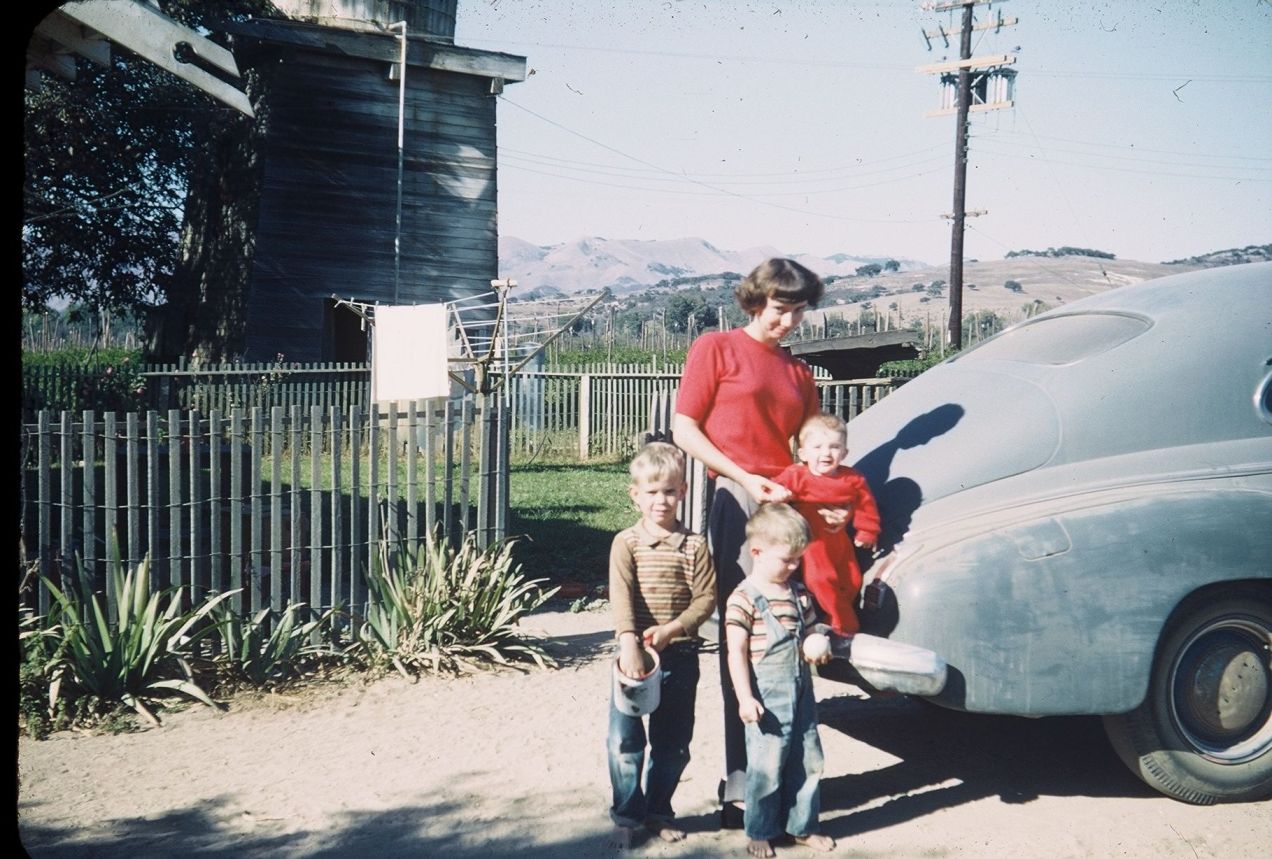

No one ever gets over playing in the mud. Shannon Family Photo, Lake Nacimiento, CA.

“Can we do it again tomorrow, can we Daddy?”

Michael Shannon grew up on a farm in coastal California and has mastered the irrigators art himself. He has masterful shovel skills, can lay pipe and knows the secret to using baling wire to clear Earwigs from overhead Rainbird sprinkler heads.

Another marvelous, evocative piece. Do you remember the irrigation pipe, a cultivator axle, wheels attached, and a tongue from discarded lumber that the Shannon lads and Bruce built to resemble, I think, a Napoleon six-pounder? It guarded our chicken pen.

LikeLike

I remember it alright. The wheels were from an old farm wagon that dad bought to make a two wheel trailer to haul irrigation pipe. The wheels you guys had were the extra set he didn’t need.

LikeLiked by 1 person