Michael Shannon.

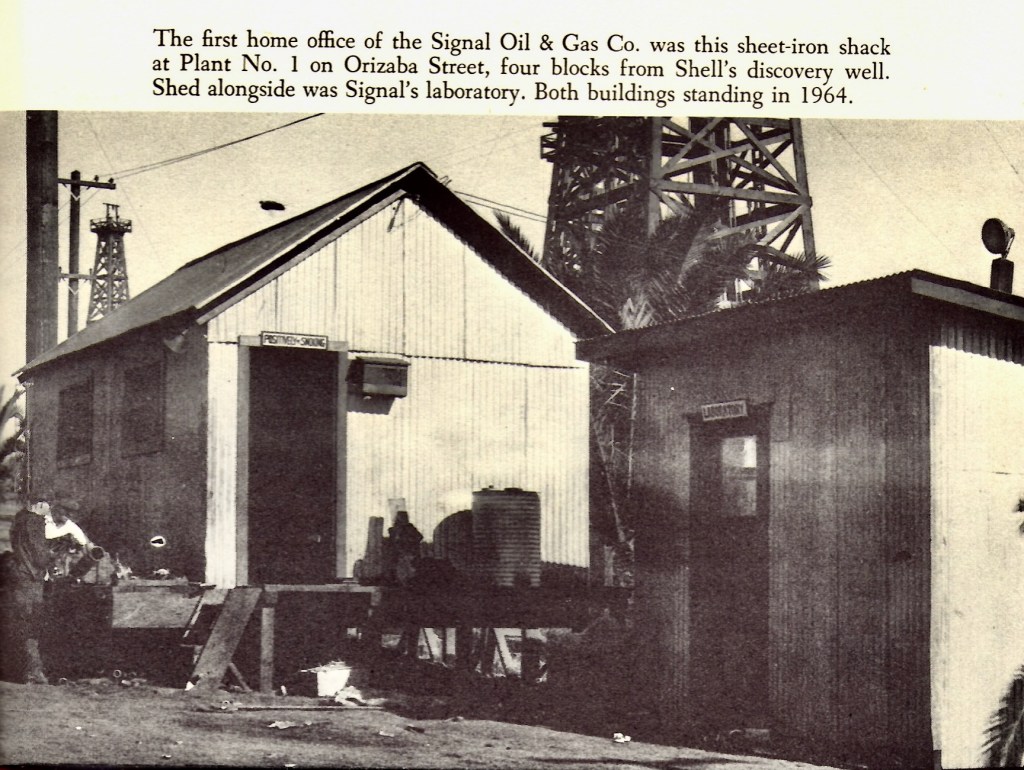

We had a small red shed on the ranch. It was the greatest place explore when I was a kid. It had cobwebs that had been spun a century earlier. There wer enough Black Widows to populate half San Luis County. My uncle Jackie said once that some of the spiders knew Captain Guillermo Dana who owned the old Nipomo Rancho. He was always saying stuff like that and you could never tell if it was true or just funny a uncle’s bushwa.

It had two doors, one at each end. They were Dutch doors which was a true novelty as I had never seen or heard of one before. The only Dutch I knew was the woman on the Old Dutch Cleaner can who looked vaguely sinister with her purposeful stride and big stick, obviously out to punish the unclean. I can’t recall ever seeing the top half closed except during swallow season. In true country style no one wasted any time doing useless things so each door was closed and opened perhaps once a year.

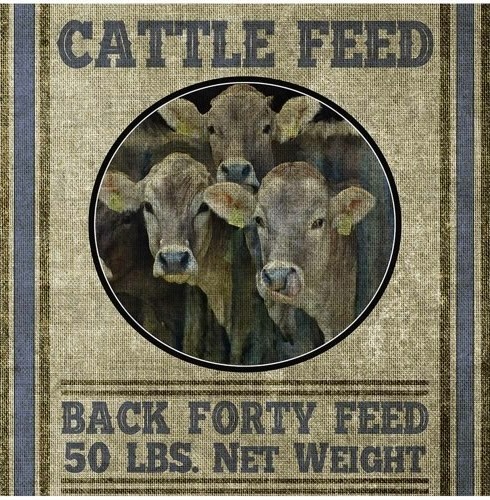

The small building served four purposes. The left side was divided into small stalls which were occasionally used to house calves that needed hand feeding or just a little extra care for a bit. For kids having a small red and white Hereford calf that you cold bottle feed, well there’s not many things that can top that. The little heifer being quite naturally friendly who would cuddle up to you or suck milk from your fingers is hard to beat. Usually one stall would be full of feed sacks, special meal, seed and always a few blocks of salt lick. Red, white and pink depending on their us. Did we lick them, you know the answer. Seeing that saving was considered a virtue, there was one stall with heaps of used and empty gunny sacks just in case. There were cotton feed sacks too, piled in a corner some, no doubt as old as the feed and grain business my grandfather, Al Spooner and David Donovan once owned.*

The sacks were home to the Kitties. Kitties is really the wrong thing to say. They were fierce predators an not interested in little boys. Their job was to keep the shed clear of mice. There are few things more attractive to a mouse than a shed packed with grain to eat. They were shy cats and not always visible, hunting was their job and during hunting hours were occupied wherever they could find a victim. No names for them, for decades the cats went by Cat, all of them. They never ate from a can or bag of cat food. They had to pull their own weight. Domesticated animals like dogs and cats were mostly for utility and not human companionship.

The little place was fragrant beyond belief and it changed it’s perfume like an elegant woman dressing for a dinner. The rich heady smell of grain, the pungent manure from the little calves and in the cold of winter it exuded a musty smell of old redwood lumber and always the rich, sweet sweet smell of Hay. Depending on the time of year wisps of dust motes drifted in the light from the doorway’s like a veil on a beautiful Spanish maiden painted by Velasquez.

The best thing though was the little corner where the tools were kept. All those drawers filled with haphazard piles of metal we assumed to be tools of one sort or another. Most carried a patina of rust, some just dusted with and some stuck together by lumps of it, glued together for no one knew how long. Wrenches of indeterminant use perhaps from some long gone piece of farm machinery, like tractors and old milk trucks, some predating the electrical motors used in the milking barn. Ball peen hammers, an old fashioned straight clawed hammer at least a century old and in the bins rusted clumps of fence staples, nails, some porcelain insulators left over from putting in the electric fence and bolts with square heads that hadn’t seen a use for 75 years.

Unique to me, a child born after the big war, many of the tools were curvilinear, embossed with the names of the manufacturer, some with molded decoration that wasn’t just for utility but for beauty. Designed by the last generation that saw pride in the craftsmanship involved in the pure design of a useful object.

The 1950’s spelled the end of the “fix it” age. Men who were our fathers had grown up in the Great Depression and as adults went to war, the most destructive war in history. Historians have said that the US defeated the Germans, not with superior tactics but with the fact that American boys could fix a tank and the Germans couldn’t. Baked into them was a certain self sufficient attitude that they could take care of themselves. They didn’t need help and like my father would rather die than ask for it. If something broke they fixed it. If something was needed they made it. They didn’t go to trade school they learned from others or simply invented what they needed. They didn’t need much, things could be repurposed. Nothing was thrown away, we had a gully with trucks, cars, tractors and farm machinery rusting in the sun where a part might be salvaged and put to a better use. If my uncle Jackie needed a stock trailer, he hauled a rear axle from the ditch, got out his tanks and welded up a frame. He dragged some used lumber from the scrap pile of odds and ends some of it dating back to some time before my great-grandfather’s day, got a handful of nails from the rusty nail bin and when he was done mixed a few shades of green paint together, brushed it on and he had a perfectly useful trailer. Rolling down the 101 on the wheels from an old Buick and a taillight taken from a Model T, With mismatched hub caps one reading Buick and one Chevrolet, It served him well for fifty years. It’s not used anymore, it sits in the old hay barn, it’s tires flat and the green paint faded but if you needed it a little air in the tires and it would be good to go.

It was all wonderfully “Make Do.”

One of the first “Essential” stores in our little town was the first hardware store. If you are a regular at one of the modern hardware stores today you might be surprised by what those old places stocked. Those old places officially died in Arroyo Grande on February 21st, 1958. The Chief wasn’t quite sure what happened but the old building built in the 1889 was a total loss. A nearly 75 year old building where the amount of Case oil. Kerosene, Lamp oil and desiccated cardboard boxes holding assorted glass fuses or leather drive belts, frayed at the edges and emitting a small cloud of dust whenever touched was simply waiting to immolate itself.

For those of us old enough to remember the dark, dusty stacks of shelve and boxes, greasy, oily wooden floors fronted by the long counter at the front, the varnish long turned to caked, flaked shreds of black chips resembling the dried mudflats of the lower valley where the adobe mud is completely tessellated in the dry late summer. The green enameled light shades hanging from the ceiling had a thick coat oily dust as they hung on the twisted copper “Rag Wire” so treasured by the rats who lived in the attics of old buildings. The tasty oil impregnated linen which passed for insulation just begged a rat to nibble on it exposing the wires which would short circuit and catch fire at a moments notice.

The fire, however she started left nothing but a heap of ashes, charcoal and twisted metal, It also ended the era of a type of store that doesn’t exist anymore except in small, isolated communities across the country.

Don Madsen was the last owner of the business which was started By Charles Kinney in ’85, thats 1885 by the way until it was passed on the Carmi Mosher in 1909. Carmi sold it to Harold Howard in 1919. Harold, a local boy having grown up with my grandfather kept the business going as Howard & McCabe until 1950 when he retired and sold it to Don whose son I went to school with. Small towns you know.

Don had worked in the hardware business since he was a high school student had returned from WWII where he served as an MP on occupation duty in Germany. He went right back to what he knew.

Occasionally my dad or uncle would need something in the way of bolts and nuts or hand tools that they couldn’t find in the tool maze of the calf shed and would be forced to actually buy something. Stores were the place for what you didn’t have. Take the broken piece to Don and lay it on the counter. He would pick it up, heft it to determine its weight then give it a serious look and say, “Yeah, we might have something like that. Let me go see.” He would disappear into the stacks of goods between the ceiling height wooden shelves and bins and begin his voyage of discovery. Assorted bangs and bumps would come from the back and finally he would return and lay a new one or close proximity on the counter. He didn’t have to say Eureka but there would be some head nodding and low noises as both customer and seller acknowledged that it was in fact “Just what I need.”

Dad would pull out his billfold, a term I have’t heard in decades and say, “How Much?”

“Six bits will do it George.”

Dad would put the billfold back in his right hand jeans pocket and then fish around in the one in front until had a small handfull of stuff, an old slotted screw with the slot turned out useless, but you never know, maybe hang on to it awhile just in case. In amongst the seeds, a piece of wrinkled Juicy Fruit gum and foxtails were some nickels, dimes and a few quarters, just enough.

Dad would ask about Clara and the boys and Don would return the favor.

Whatever that piece of hardware, it would someday, when it’s immediate usefulness was done, end up in the calf shed where it likely still resides.

After all that old hardware store was not a too distant kin to the calf sheds.

When she burned in ’58 it marked, in a real way the end of frugality nurtured by “Make Do” and the way we live now where everything has a date on which it will magically die.

Epilogue.

The though that planted the seed for this story was a trip to the local hardware store the other day. Big, bright and shiny, all the trim painted fire engine red and the first thing you see when the automatic doors open is a large open space with military straight rows of Barbecues. Stainless steel, black enamel, wood burning, pellet burning or gas or electric. Line up like they just graduated from boot camp they are surrounded by all the accouterments designed to make you a perfect cook. Tens of thousands of dollars worth.

There is a paint department where you can buy hundreds of different colors. Anything to suit your fancy. They have more cleaning supplies, mops, and brooms than you can conceive or could find at the grocery store. Every one is persistently helpful but no one knows much of anything about anything. But they wear a red vest to show that they might. Very official.

Unlike Don, they will look at your problem, scoff, and advise you to buy a new one, or a box of fifty when you need just the one. And believe me, the inferior new one that will never deserve a place in the calf shed.

Dad Shannon at the BBQ pit. Family Photo

For a kid that grew up with BBQ cooked over a pit which was just a handy hole behind the house and a grill made of heavy rods left over from some job they did and whose grandparents painted their dairy barn and silo pink because there wasn’t enough of either color available during WWII so they just mixed them up and it was good enough and a great lesson too.

“Make Do.” That was it.

Cover Photo: The old hardware store on the right in 1906.

Note: The Madsen’s moved their store across the street to the old Donati building and prospered for many years but it was never the same.

Michael Shannon has been known to keep random pieces of lumber for fifty years, you know, just in case.

Please Subscribe.