Category Archives: Uncategorized

It’s Not Vegetables You’re Buyin’ Lady,

Its a mans life you hold in your hands.

My dad’s family were farmers in Ireland. That’s what they knew. Like all immigrants they came to America for opportunity. They came because laws in Ireland held them captive in a system of government that placed no value on small farmers. Just twenty years before my great-grandfather was born, it was still illegal to educate Irish children. An Irishman could not vote nor own land unless he was of the ruling class. The Potato Famines of the early 1800’s began the drive for immigration in which 1.7 million Irish came to America between 1840 and 1860. This flood from Ireland continued, unabated for 50 years. Today there are about 36 million americans of primarily Irish descent. Only about 6.4 million Irish still reside in Ireland.

An Irish crofter, as farmers were known, held property in trust from the large landholders who actually owned it. The average Irish small farm was roughly one eighth of an acre. Can you imagine living and growing subsistance crops on a piece of ground only 5,400 feet square? Thats about 75 by 75 feet! The United States, stretching for over three thousand miles to the west was an almost unimaginable thing. It was near impossible to imagine how large it was. Even today people of this country cannot imagine it’s size.

My great-grandparents, the Greys, Samuel and Jenny were from Ballyrobert Doagh, a crossroads on the river Doagh in County Antrim, Ireland. They came to America on their honeymoon in 1881. The sailed on the packet ship State of Alabama which ran a circular route from Glasgow, Scotland to Belfast, Dublin and Cork. Once loaded, it made passage across the north Atlantic. Those trips took as much as 12 weeks to make. The ships themselves were combination steam and sail which was somewhat of an improvement over the so called “Coffin Ships” that made the trip some thirty years earlier. During the Irish Diaspora as much as half the steerage passengers might die enroute. All of the major destination cities in the United States and Canada featured mass burial grounds filled with the hopeful.

They boarded the States Line ship “SS State of Alabama” in Belfast and arrived in New York on the 6th of June, 1881 after a quick summertime passage of just 18 days. Sam and Jenny made it to New York harbor where immigrants were held in quarantine on board until cleared for landing. Once cleared they at disembarked Castle Gardens on the lower end of Manhattan Island.

Sam Grey worked all kinds of jobs as he made his way west to California, arriving finally in San Leandro and then down to the the Salinas valley where he grazed sheep. His wife Jenny had relatives living in the Oso Flaco area of California and eventually they came here. They rented some land along Division Road and he grew potatoes of all things. Ironic, but a decent profit. My grandmother was born in that little house, the second of there eventual seven living children.

That child grew up to be my dads mother, one of a family of farmers and dairymen that included McBanes, Mcguires, McKeens, Moores, Greys and Shannons. Today politicians refer to this as chain migration but they are fools. Family following family has always been the rule, always will be. The Irish didn’t ask for any hand out; they wanted a way out and they were willing to work to get it.

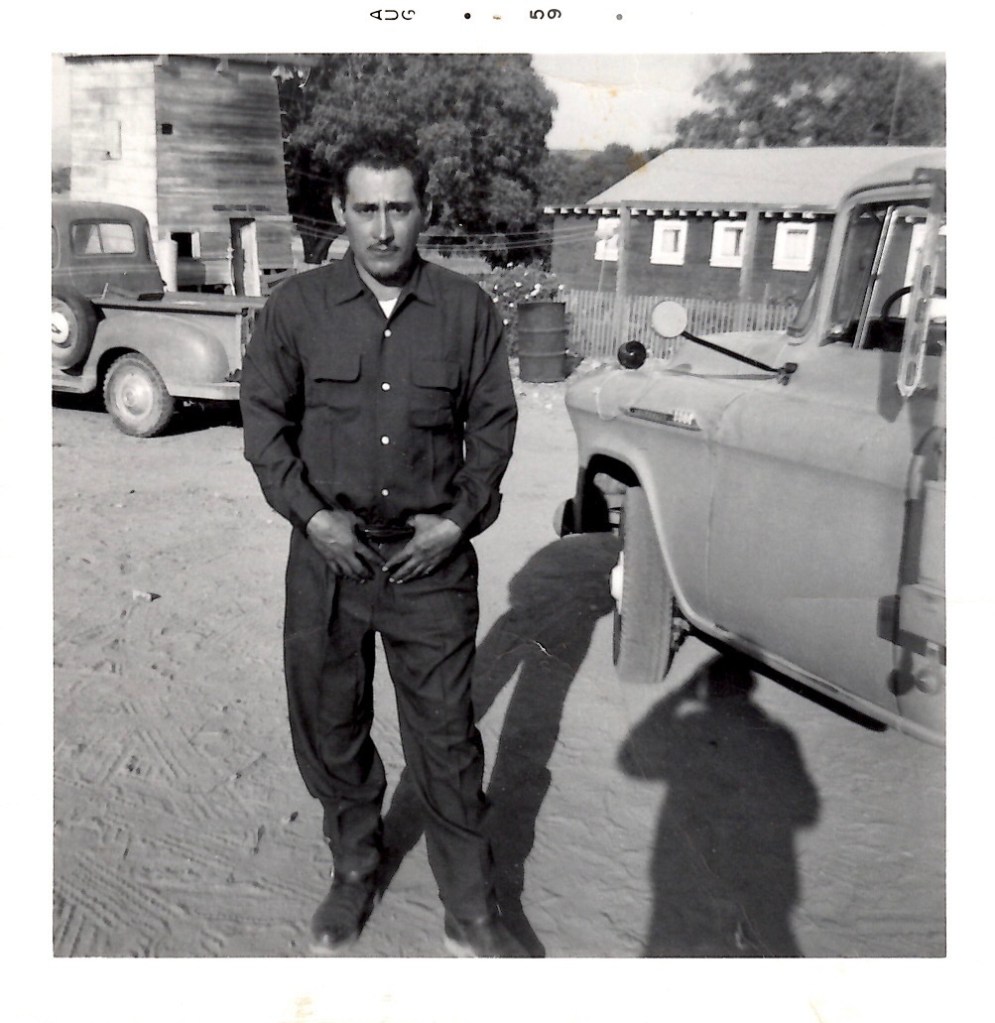

Agricultural servitude is term applied to those that work the ground for pay, usually meager. It applies not to just the field laborer but the owners too. My father, the grandson of Samuel Gray was one of these men. He was raised on a dairy farm as they used to be called because not only the milk cows were raised there but the oats to feed them. My grandparents also raised beans, peas, tomatoes, hogs, turkeys and for comic relief, many, many dogs, some who stories are legend in our family. No goats though, Grandma said that only shanty Irish raised Goats, plus the church taught that animals with cloven hooves were unclean and satanic. Thats the way she thought and thats the way it was.

Annie Shannon, my grandmother about 1925. She is 40. Hillcrest Dairy, Arroyo Grande, CA. Family photo ©

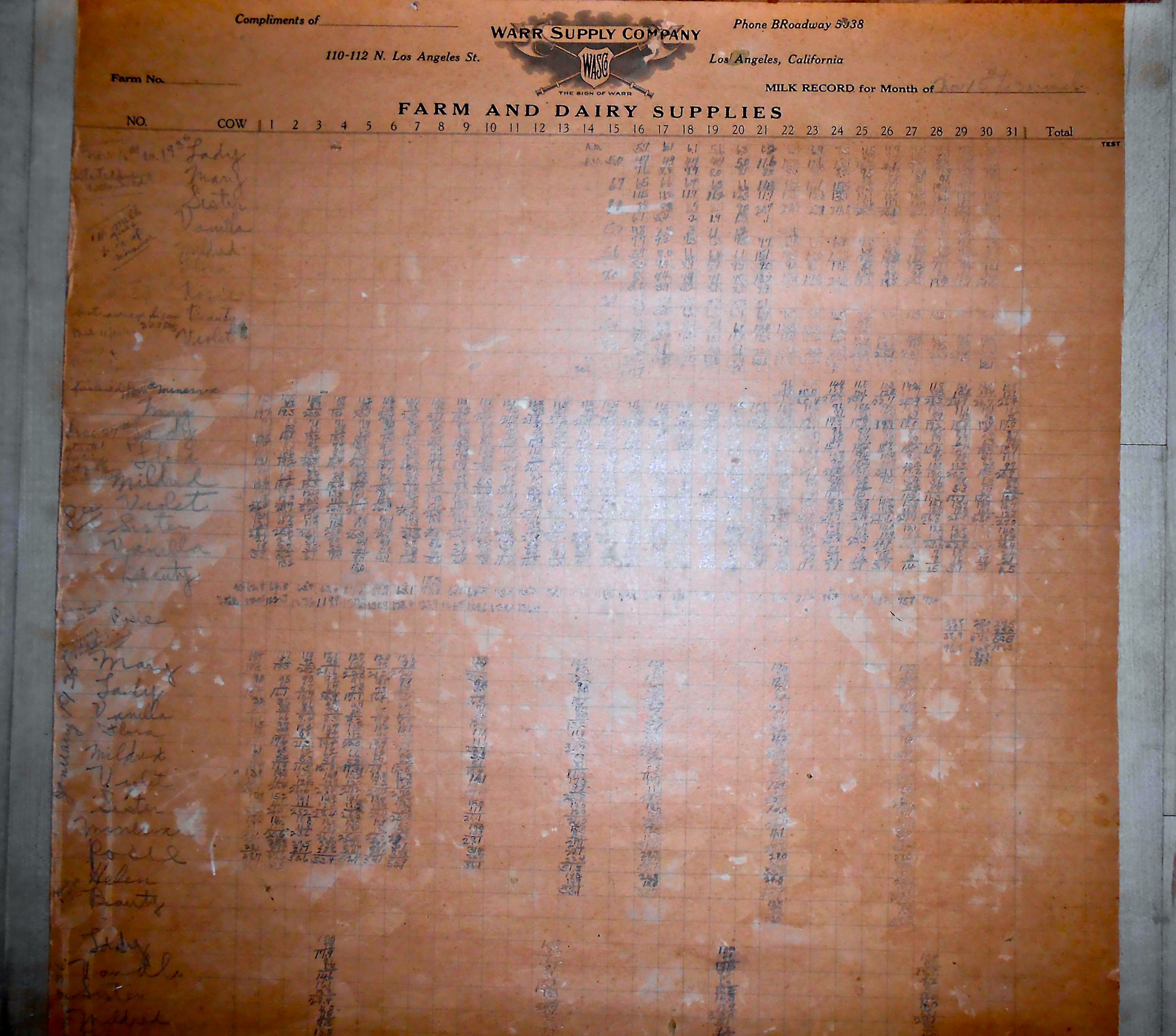

Dairies are the chains that bind the farmer to the ground. Cows are milked two or three time a day and the dairyman follows the old rule, “Dark to Dark,” when he works. Little boys like my dad and uncle learned the lesson early for they had to begin pulling their weight as soon as they were big enough. Kid chores like feeding chickens and collecting eggs and as they grew, the load became heavier. As teens they rose before dawn, went up to the barn to help with the milking and then the bottling and cleaning. Off to school for the middle of the day, they returned in the afternoon for the evening milking. Every day seven days a week, twelve months of the year including all holidays. The cows took no time off and neither did the customers.

When I was little my dad was farming in the upper Arroyo Grande Valley. He grew what are known as row crops. Vegetables like celery, broccoli, lettuce, tomatoes and string beans were what he raised.

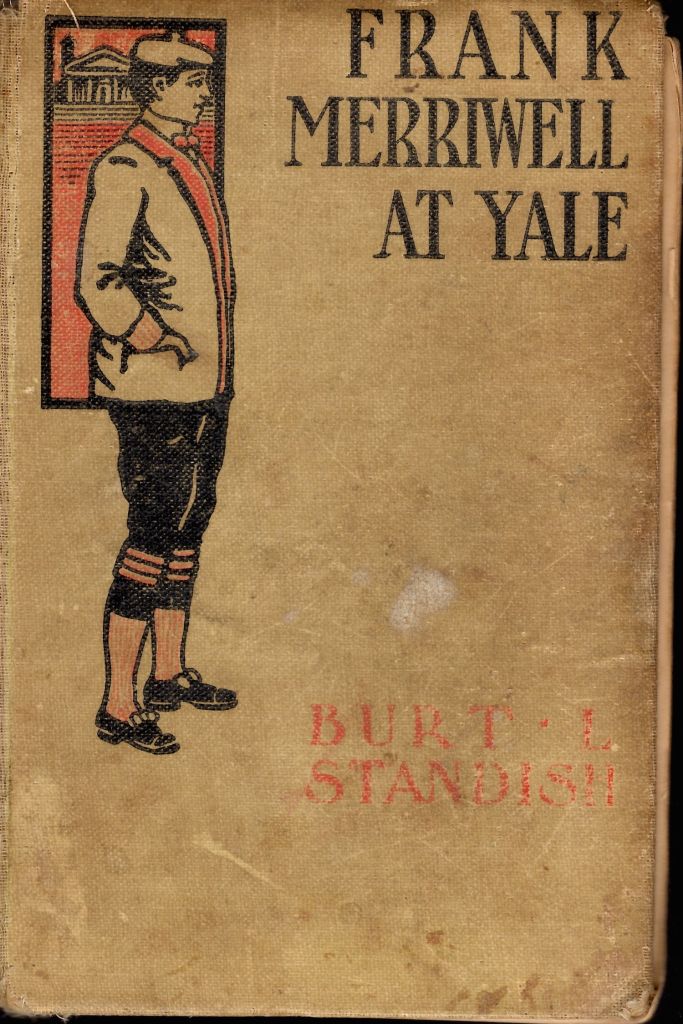

Unusual for a farmer of that time, Dad was a 1934 graduate of California Berkeley. He once told us that the main reason he went to college was, one, my grandmother had graduated Cal in 1908 and she wanted him to go, two, his father wanted him to study the law but most of all he went because he’d read Frank Merriwell at Yale, a pulp fiction book from the early twentieth century about Frank’s grand adventures at Yale. He and my uncle Jackie used to walk up to the old Union hall, fondly known as the “Rat Race”, which was at the corner of Mason and Branch streets. On Saturday afternoon they’d plunk down a nickel and sit down in one of the wooden folding chairs or the eclectic collection of press back chairs salvaged from somebodies kitchen and watch what were still called Flickers because they did,flicker Harold Lloyd, Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, Fatty Arbuckle, Mabel Normand and the madcap cops from the Mack Sennet studios made kids laugh. The “freshman” starring Harold Lloyd or “College” from Buster Keaton told an age old story. They had storylines that led Dad to visualize college as a place where Nerdy grinds were picked on by strapping young athletes, ignored by pretty girls but somehow managed to save the day by winning the big game on the very last play. The pulp novel, “One Minute to Play”, which we still have features a football hero forbidden to play in college by his pastor father. A hundred years have passed since Dad and uncle Jackie sat on the edge of their chairs in that drafty old dance hall but the plot remains the same. Those things, he said were his primary reason. They were a good as any. And he did have a great time to boot.

He came home to Arroyo Grande after graduation. It was the middle of the great depression when work and money were scarce. Businesses were barely hanging on and opportunities were few and far between. Choices had to be made.

Farming and ranching were familiar things to him though he later said that he didn’t want to be a dairyman because the work was so relentless. He chose row crops instead. Which, when you think of it is only slightly better. It’s still six and one half days a week, dawn to dusk though it slows in the winter some. Fewer crops but more adobe mud, there is your trade off.

Slogging your way down the rows dressed in oilskins holding the slippery handle of your 12″ Broccoli knife, slippery with mud, hands with no gloves in the rain, cold at 7am, still nearly dark. Left hand grasping the stalk below the leaves, a blind slice, the cut and throwing the severed head through the air and into the cart being pulled behind a wheel tractor. The driver and the tractor set the pace and it’s relentless. Head down, sucking mud, mind numb, no time to think, just do the job. For minimum wage. They tell themselves that there is no one who will do the work and some pride is taken in that. What else can you do?

It’s like the old saying, a boy tells his father after his first day of bucking hay, “I sure hope I don’t have to do this for the rest of my life.” Before he knows it, sixty years on he’s still doing it. Life is like that.

There is just something about the orderly manner in which crops are grown. All the preparation and finally after walking through the planted but still barren fields looking for that tiny two leaf sprout which ever and ever again promises that life will renew. That is the true farmers delight.

My father never bought a new truck in his life. He though of it as showing off. He didn’t glad hand or seek out the company of other farm men and contractors, no breakfast meetings at Goldies with the three percenters and the reps from NH-3 or the seed salesman. It was wasted time. If he needed them they were just a phone call away. Though all of that is a tried and true way of doing business he considered it a waste of time.

Time was better spent managing his crops for he was extremely proud of produce. As a boy I worked in his packing sheds, wherever they might be. He had more than one ranch. He would take me out to the Berros ranch or up to the one on the Mesa and I would pack vegetables. One of the keys to understanding my father was to know that he would never cheat you; ever. Every vegetable is those boxes was to be perfect. The prize tomato on the top was exactly like the one on the bottom. In a flat of Chinese peas which held hundreds of pods, every one had better be perfect. It’s what he expected of you and its what he produced for the buyers. In that way he taught me to be meticulous about any job I did. As a 13 year old I didn’t get it, it made the job slow and monotonous but somehow the lesson stuck. I’m not sure if he saw it as a lesson but It’s what he expected of himself and it was the same for me. I thank him for that.

I remember riding with him in the pickup and dad pointing out the farmers who couldn’t plow a straight furrow or ran their irrigation water onto their neighbors, those things mattered to him. It’s funny because our tractors lived outside and were dirty and rusty and in the slowness of winter the weeds grew up around them and they looked abandoned. He didn’t care about that, they just had to run. Their only purpose was to serve the crops. Crops, perfect, tractors, not so much.

My dad was thirty three when I was born. When I was a pea packer he was in his middle to late forties, his prime years and had been a farmer for a quarter of a century. By the time I graduated high school he’d been at it for thirty years. He’d seen a lot of changes in farming in that time but was about to face the death knell of the family far, consolidation. After the wars population surge there were many more mouths to feed in America and the pressure on the smaller family farms to remain profitable increased.

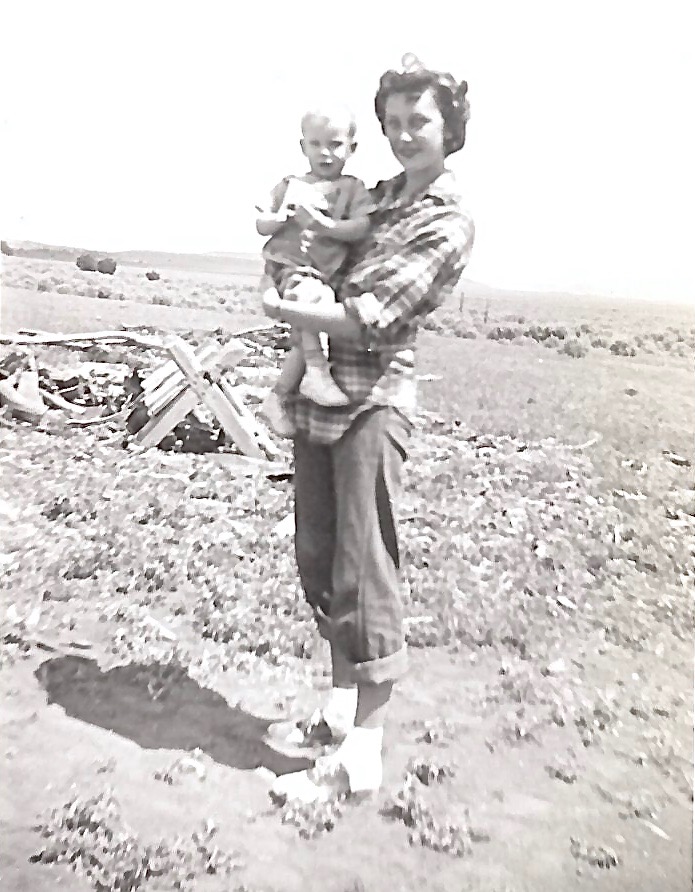

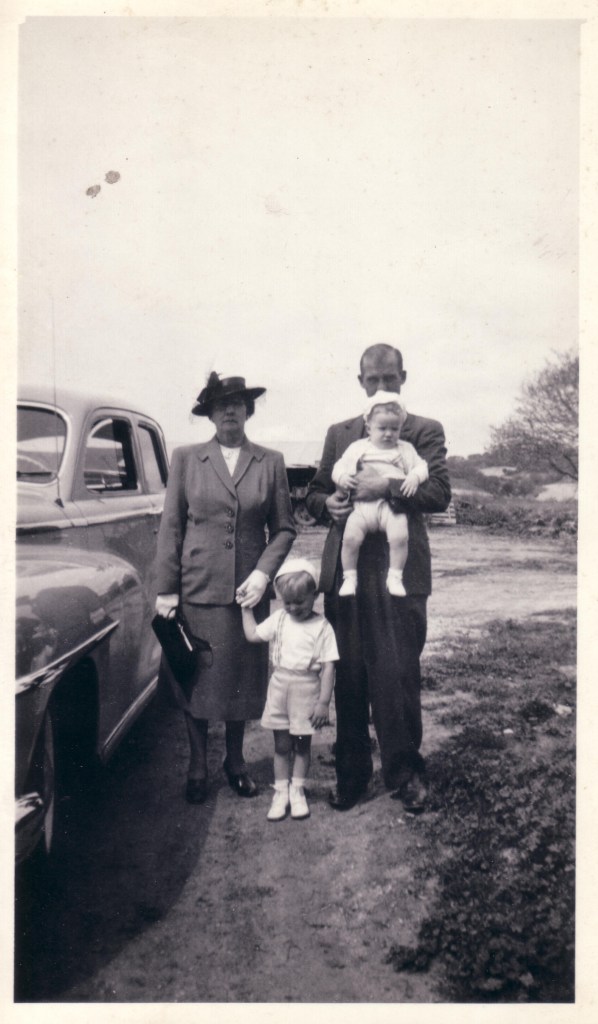

Daddy and me, first birthday 1946. Family Photo

The Vegetable packing houses which contracted with the individual growers and the advent of huge grocery chains increased demand for production. For example my dad grew celery on contract for a local packing house which sold celery to grocery chains all over the country. No longer did the little local trucking company haul your produce up to the San Francisco markets or down to Los Angeles. Your celery might be going by train to New York or Chicago and in bulk, orders made up of the crop from a dozen small farms. Some farmers, more businessmen than growers formed co-ops or bought out the individual family farms. This allowed the large grower to make demands of the brokers and introduced economies of scale to lower their production costs. This worked against the small farms like my dad, the Betitas, Kawaguchi’s, Cecchetti’s, the Silva brothers and My great uncle John Grey. Their was no more growing land available and they began to be squeezed out of the markets. It wasn’t as if there produce was inferior but when it came to essential services they needed they were forced to wait in line. What this meant is that vegetable market prices which fluctuate literally hourly are a target everyone is shooting for. A delay in harvesting and shipping can be very costly and when a large grower demands that his celery be cut and shipped on the day or days your crop is scheduled for it can cost you your profit. This in our little valley. Imagine Ralphs demand that a vegetable broker not only meet what they are willing to pay but that the broker must supply every Ralphs in California or even the nation. No family farm can do that and thats why they have gone the way of the Dodo bird.

In the nineteen sixties you could count down from the site of Santa Manuela school to the dunes by family name. Biddle, Grieb, Donovan, Talley, Antonio, Evenson, Fernamburg, Cecchetti, Ikeda, Kawaguchi, Shannon, Sullivan, Coehlo, Berguia, Gularte, Waller, Reyes, Betita, De Leon, Dixon, Fukuhara, Marshalek, Fuchiwaki, Saruwatari, Taylor, Kagawa, Kawaoka, Matsumoto, Nakamura, the Obyashi brothers, Sakamoto, Sato, Kobara, Sonbonmatsu, Hiyashi and Okui. There were Phelans, Donovans and Elmer Runels too.

The Betita Boys, 1960’s running string for pole beans. Used by permission

See, the thing is you gotta be in it to win it. Farming takes a gamblers approach. Farmers know that farming is an extreme investment. Finished crops return a very small percentage on the money you put into them. Equipment is expensive if you look at the cost of just an individual item like a Caterpillar. What few think about is the add ons, the Disc, Harrow, plow and the roller. There is gasoline and diesel, oils and grease to be paid for. You have to have a tank to store the fuel. Unless you have kids of an age a driver must be paid. Seed, fertilizer, pesticides and the cost of running the water pump. Who moves the irrigation pipe? How about the crop duster?

Where is the labor to be had. That’s rough and dirty work usually done by folks with few other options which in itself brings problems of attendance and theft. Drinking before, during and after the job. This is the kind of work done by the desperate. People so poor that they will steal lettuce knives, the baskets used to pick vegetables, shovels or even your shirt if you leave it lying about. For us this problem was abated with the introduction of the Bracero program which brought young Mexican men into the country to replace the field workers who were in the military. After the war the soldiers didn’t come back so the immigrant program was continued. Until 1964 this program supplied nearly five million workers to farmers in 24 states.

We, and most of my friends grew up with these guys which, I think gave most of us an appreciation for different cultures. To leave your home and come across the border to work for people who didn’t speak your language and had no interest in your culture was a form of bravery that I understood.

Nonetheless the small farmers struggled and when we had an early, very hard freeze which killed nearly every crop in the valley it spelled the end for many. Bank loans were not forthcoming, there was no crop insurance, no Federal subsidies and in most cases no cash on hand to pay your vendors. Bankruptcy was an option of course but men like my father and especially my father would never admit total defeat. The bills were piling up and some companies, even ones run by close friends were demanding payment. I can’t imagine how he did it but he just put his head down and paid what he could. It took years to crawl out from under the debt. He forbid my mother who worked to pay off one dime, it was his debt. The big freeze was only one disaster. Down in Berros the deer were bold enough to come into the tomato fields and eat the fruit in broad daylight costing thousands of dollars. He got a permit from the county to shoot them but you had to dress them out and deliver them to the county’s general hospital which became a huge job in itself. He had to give it up. I was a senior in high school then. One year storm winds blew down acres and acres of pole peas, the mainstay of his operation. You could look out our kitchen window and see the field with the ripe, producing vine lying flat on the ground. One winter there had been so much rain that the tractors could not get into the fields to harvest the celery. Crop loss, natural disaster and the dominance of the larger operations was like one step forward and two back.

I can’t imagine the courage it took to move ahead but in 1980 he had, had enough. He and my uncle sold my grandmothers cattle ranch and he used the money to retire. In those days it was rare for a farmer to have a pension and most depended on Social Security to survive. So he took some of the money and bought a lot in town and I built them a retirement home. He always said he wanted it there so he could see the old home ranch where he was raised. Just like the home I grew up in where you could look out of the kitchen window and see the crops grow and the neighbors pass by the new house had that big picture window next to the kitchen table where he could sip his coffee and see where his life began.

Mom and Dad with their three sons in 1986. New house. Family Photo

So they left the ranch near the four corners and never looked back, his last and favorite dog moved to the junkyard on Sheridan Road up on the mesa and they settled down in the new home at the corner of Pilgrim and Orchard streets. Mom and Dad lived quietly there, she passed away first and he followed a few years later. He missed her because he loved her so and his last years were lonely and like many old folks slightly bitter for what was lost. Weighed on the scale of life I believe there isn’t enough Gold on earth to level his worth as a man; old fashioned in his beliefs but a superb father which is what counts with me. It’s funny but as a little boy I called him Daddy which I outgrew as children do but at the end thats what he was, my Daddy.

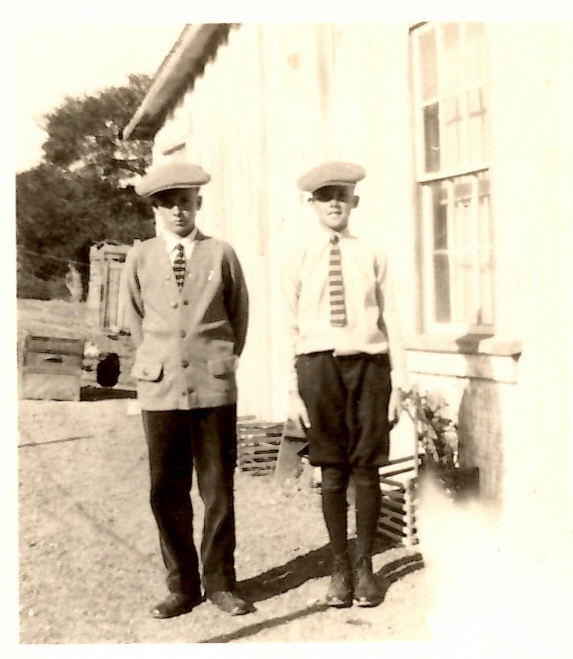

- Cover Photo: Jackie and George Shannon on the dairy. 1922. Family Photo

Michael Shannon is a writer and a son. He writes so his own children will know their history and who they are.

THE GHOSTS

Michael Shannon

I met Billie at the door. She had the Key. She handed it to me and I slid it into the old mortise lock on the side door and pushed it open. The rusted hinges resisted the movement a little but finally allowed us in. The narrow hallway ahead was redolent of dust and the peculiar smell I’ve always identified with old buildings. Ahead, the stairs to the 2nd floor lodge room were nearly covered on the left by stacks and stacks of newspaper galleys collected by the Historical Society from the old Arroyo Grande Herald. Some of the newsprint had come from former owner and publisher Newall Strother’s home on old Musick Road, found there upon his death stacked nearly to the ceiling in every room. A gift unintended, left us by a man who just couldn’t bear to throw them away.

Dim light with legions of dust motes drifted slowly in a tiny breeze from somewhere in the old building. Up the stairs there were windows at the second and third floor landings, lighting the stairs with the particular glow of dirty old glass, aged and coated inside with decades of smoke and outside by the grime blown against them by weather. A filmy yellowish khaki, gently drifting cloud that only exists in old unused buildings. It tinted all vision.

“Let me show you the lodge room, no ones been in it, I think, for many years,” she said. I followed the little woman up the stairs. Dressed in slacks, what looked to be a mans old dress shirt, girls old-fashioned tennis shoes, her grey and white hair taking a glow from the old windows, she led the way up.

Her name was Billie and I had known her literally all my life. She was the granddaughter of Don Francisco Branch, the first of the Rancheros to bring his family up into the northern part of the old Spanish Cow Counties in 1837. He received a land grant from the Mexican government of nearly seventeen thousand acres of un-cleared nearly virgin land which had remained untouched by any but the few Chumash for thousands of years.

Billie’s father, Thomas Records, from another pioneering ranch family, had married Miss Lucy Jones, a granddaughter of Francis Branch. Billie was historical royalty in the little town we lived in. She kept things. My dad said that she and her sisters weren’t called the “Record sisters” without reason. She had a house full of stuff and a mind chocked to the brim with notions about who did what and how. She knew the bloodlines, the natural intermarrying of citizens in small towns. If you needed someones antecedents, she knew them.

Me and Billie in Madeline, California 1946. She’s 31, I’m 1. Family Photo

She and my father grew up together and had always been great friends. When Dad found my mother, Billie took her right into the Arroyo Grande family. She was the kind of person that, when you saw her on the street there was nothing to do but to pull over and talk to her. After my father died she came to the house with a box of, you guessed it, records. She had squirreled away news clippings, letters and other things about our family. In the box were my fathers high school football and basketball varsity letters. She had put them away and saved them for seventy years. That’s a story I wish I knew. I’m sorry that I never had the chance to ask her or him why she had them. He went to Arroyo Grande High School, she, Santa Maria but somehow she ended up with them. There is a story there, lost forever I think.

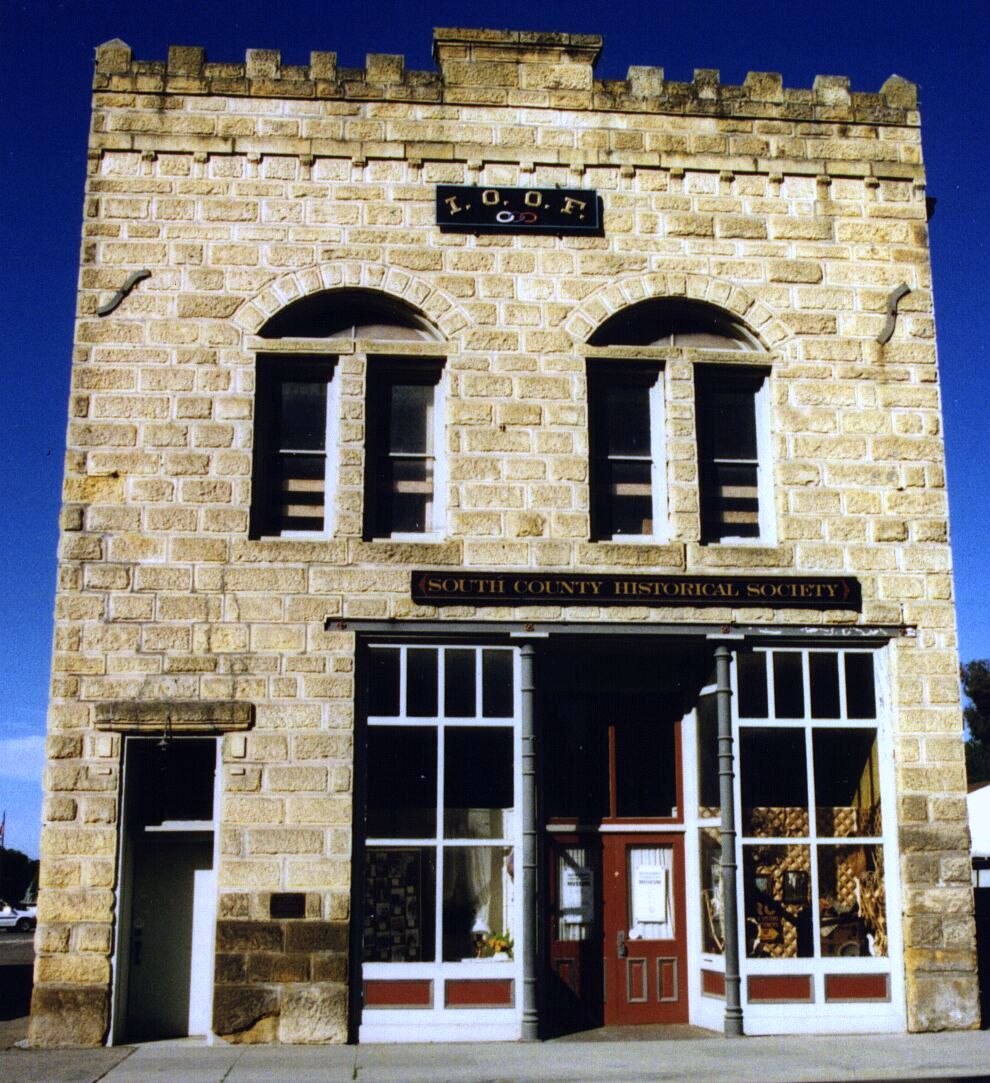

We were at the old hall, Odd Fellows 253, because as a new board member she wanted to give me a guided tour of the old building. The local History Society had recently received title to the nearly one hundred year old building for the grand sum of one dollar from the last surviving member, Gordon Bennett. The board and membership were fixed on the idea that we might secure funding to refurbish the old landmark.

Built in 1903 as Lodge 253, the old building had lain vacant for years. The Arroyo Grande Sandstone of which it was made had come from the old Patrick Moore quarry on my grandmothers ranch.

Left, Thomas Shipman brother in law to Jenny Gray, Annie Shannon in back with her mother Jenny and Maggie Phoenix in front of the hall.circa 1905. Family Photo.

We were at the old hall because as a new board member she wanted to give me a guided tour of the old building. The only time I had ever been in it was as a teenager. I had gone with my father to pick up his blue ribbon won for the best Chinese Peas at the Harvest Festival vegetable contest. The local farmers display of all the different vegetables grown in our valley took up the entire first floor. While we were there he pointed to the big windows in the front of the building and told me that my great-grandfather Shannon’s body in his coffin had been displayed there when the ground floor was the towns undertaking parlor. What does a kid say to that, I couldn’t imagine such a thing but I’m sure it was true, they used to do things like that. He said my grandfather who was a member of the Odd Fellows had taken him down when he was just twelve to see Dad Shannon, as he was called, as his body lay in state. In the window, not a church, but in a window.

The local History Society had recently received title to the nearly one hundred year old building for the grand sum of one dollar from the last surviving member, Gordon Bennett. The board and membership were fixed on the idea that we might secure funding to refurbish the old landmark.

At the first landing a quick turn to the right led into the lodge room. This was where the members met. It was obviously well used, the old carpet was faded and threadbare in places. The benches along the walls had seen better days, their varnished seats rubbed bare by generations of shifting bottoms. The curtained windows their muslin drapes transparent and fraying at the bottom filtered the sunlight creating a sense of timelessness as if the members had just left. I suppose they just had in a way.

The tour finished we turned and stepped onto the landing to head back down. I stopped and asked Billie where the next flight up went and she said it’s just an old storage room I think but you can look if you like. She turned and headed down, I turned and headed up the short flight. Just curious.

The door was closed, the old stamped doorknob mounted in its long rectangular faded brass plate turned stiffly. As the door tuned on its hinges the unmistakable odor of age greeted me as I stepped inside the dim interior. It wasn’t a storage room at all. Festooned with cobwebs nearly invisible in the gloom was a full sized six pocket pool table. Covered with the dust of decades it’s woven leather pockets still held the ivory balls fallen there during some last game played long before my birth. Two pool cues embedded in the cobwebby drift of aged dust lay on the felted top as if the players had just left for a meeting downstairs. Scoring beads hung from a long leather string indicating the final score. Overhead was a gas light fixture, its copper tubing rising to the ceiling and from there to a brass valve on the wall. Each burner had a age caked glass chimney under a brass shade, four of them once providing light to the table. Near the door was an ancient porcelain mercury switch that controlled a single light bulb hanging on old, old Ragwire directly over the sink. Electricity must have been installed sometime after the gas fixtures. A back up I suppose.

The sink was simply an enameled iron square basin. It was cradled in a pair of iron, triangular brackets mounted to the wall. The rusted old brackets had the image of a camel suspended in the frame. The drain was straight and likely just ran outside the wall and down the side of the building, simple and practical.

A small table and two cane backed chairs stood guard, one with a frayed seat. One old glass stood solemnly on the table, the bottom holding the dried remnants of whatever it held last.

A shiver ran down my spine. This was the place members retired to have a nip, play some pool and share stories, smoke or chew a five cent cigar. A place where hats didn’t have to be removed for ladies, for there would have been none. Breath slowly, squint a little and you can see Judge Webb Moore lounging in a chair tipped against the wall as Jack Shannon and Hu Thatcher chase the ivories around the table. Warren Routzhan and Ben Conrad confer in the corner, waiting their turn while Fred Jones and Harold Howard laugh over a George Grieb Joke. No Odd Fellows title needed here, no Noble Grand, no Rebekahs just some good hard working men sharing their time.

None of them would have been caught dead in a real pool hall for they were respected members of the little community they lived in. Here, on the third floor hideaway the rules were different. as they should be.

I waited a bit, then quietly closed the door knowing that I had surely caught a ghost.

Michael Shannon and his extended family have lived in Arroyo Grande, California for six generations.

THE IMMIGRANT

Michael Shannon

The Immigrant

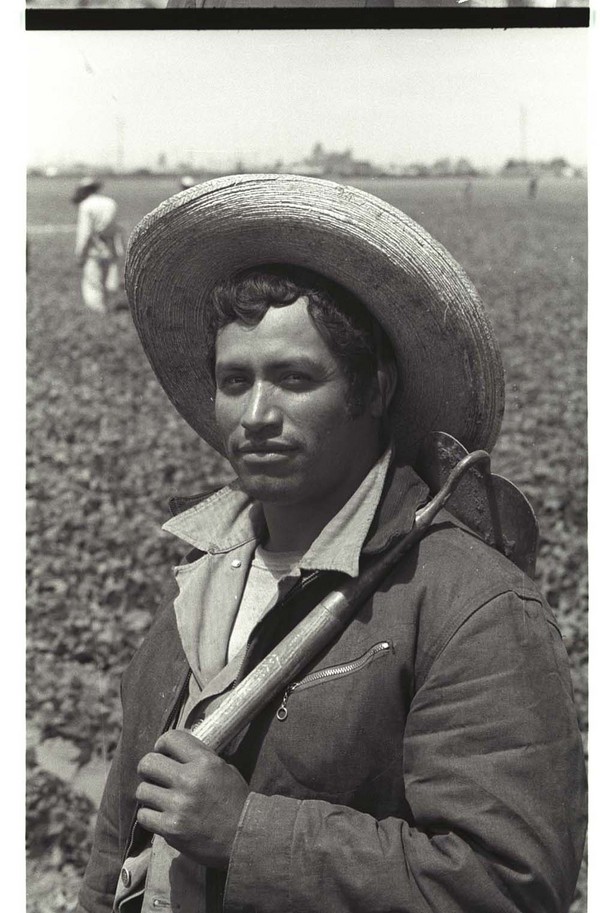

He slept in the old rattling, wheezy school bus as it found it’s arthritic way. Most did. They hoped for just five more minutes, one more minute, please. The bus turned off the two lane road, bumped through the borrow ditch and rattled down the dirt road to the fields. The road baked as hard as steel, rutted, criss-crossed with the stampings of tractor wheels shook the old yellow bus with the fading tracery of San Luis County Schoolson its side. With a lurch the bus pulled up, the doors wheezed open and the driver said, “Get off.”

Down the aisle he shuffled with the others. The stale smell of yesterdays sweat hung about with evil odor of whiskey farts, bad breath and musty, not washed enough work clothes. He stepped down, he stretched cramped muscles, a thankless gift from the day before. Holding his pail with the tortillas, beans and rice rolled in tinfoil. he walked heavily to the wire bound basket in the pickup bed holding the hoes and flat files which were the tools of his trade.

Taking a deep breath of the sparkling air flavored with the last vestiges of the nights foggy dew, he headed down the row which seemed to stretch to infinity the ends still shrouded in the ground fog of early morning. He arrived at the spot where he’d quit the day before. Taking his water bottle off, a glass gallon jug with a length of binder twine tied around the neck in order to make it easier to carry, he stood tall, arching his back as he made a last futile attempt to disappear yesterdays pain. With an audible sigh he bent to the work.

Scattered like the seeds they tend, across the fields as if flung there, their backs humped up, faces the color of the dirt. they are bent close to the ground as if part of it.

Hoeing, weeding and thinning the delicate tomato seedlings already exuding the distinctive faint odor of their kind. The width of the short hoe with its 16 inch handle determined the spacing of the plants which would be allowed grow to maturity. All others sacrificed, Tomatoes, Malva, thistle, purslane and mustard, tiny as a fingernail, chopped by the rhythmic rise and fall of the hoe. Mass murder.

Held halfway down the handle for balance the hoe slipped between the plants removing all unwanted growth. The Tomato seedling with its two jagged leaves was left alone. Again. Again. Again. Tens of thousands sacrificed to the scuffling blade.

Photo ; Leonard Nagel, National Museum of Natural History 1956

Bent double at the waist, feet crossing again and again in the narrow furrow, he moved on. Already his back hurting. The pain began at the waist, spread down the backs of his thighs, the tendons behind the knees and up his spine to the shoulders and the back of the neck. Stay stooped, don’t straighten up it hurts less and the boss will see you if you do stand. There is a family to feed.

The heat rising, the sun seemingly stationary, the row endless and if you ever get to the end you must turn and face it again. Ten hours. All around the rhythmic pace of men, no talking, waste no energy. Can’t stop to smoke. When no one’s looking, a quick sip of tepid water. Sweat dripping from brow into the eyes. He straightened slowly, careful to ease the muscles lest he be crippled. He bent back over the row, trying to ease the pain of the hoe in his palm, turned red from the constant movement of the wood against skin. Back to it and all the while the ache, the ache; never ending.

Almuerzo en el Campo. Photo Shannon 1950’s

Noon, an unbelievable half hour crouched in the shade of the bus. Almost asleep while eating. Eyes closed until wakened by the shuffle of other men, cursing, groaning, headed back. Bloated with lunch, gut heavy, aching, he bent over the row. Shuffling sideways, his legs crossing and uncrossing, the Cortito rising and falling, he labored on like a condemned man, he administered his own torture; held it in his own hand.

Usando el “Cortito,” ( El Azada) San Luis County, California. Family Photo

His vision narrowed until the only thing visible was the hoe and the tiny green plants. The mind going down a dark hole, focused only on the intolerable ache and the rhythm. Slide step, drop and pull, crossover step, drop and pull. He followed the bent men.

The sun slid achingly down the sky, the men moved on across the brown earth. He hardly thought, focused only on the pain and the chopping. Quitting time did not exist now, only an endless wilderness of sameness. Up and back, up and back.

At first he was hardly aware of a new movement, men jumping across rows and trotting to the bus. IHe realized with a start that it was quitting time. Slowly straighten, stretch the bunched up muscles in his back, finally standing upright he followed the others into the bus. Stepping over men prone, unable to take another moment of back bending, he found a seat.

He walked to the barracks leaning oddly backwards still trying to stretch the twisted, corded muscles in his back. Propped on his cot, feeling the new lumps of muscle in his aching spine he said to himself, “I will never go back.” But the pay was one dollar an hour and his family, in Chihuahua needed the money. An hour of work bought a meal, two, a day of food.

He was a long way from home, unable to see a return, he had no choice.

Epilogue

The Chumash, The Mestizos, the Chinese come to Gold Mountain, the Irish Navies cast loose by the southern rebellion, the Japanese, Filipinos, Azoreans, Germans, Italians, Norwegians and Swedes. The Russian Jews and the those fleeing Eastern Europes despots. Vietnamese fleeing Ho Chi Minh. Now, Haiti, South and Central America, Mexicans, Hondurans, the disposed of Oaxaca, Chiapas and the raging Cartel wars. Day laborers from Mississippi, Motel maids from Chicago, tractored out sharecroppers from Missouri, Arkansas and Oklahoma, they all come for the same reason.

America and California are built on expectations. You can start all over here. That’s why people come–to start all over and become somethng new. They put up with tenements, sweatshops and grinding stoop labor, not in resignation to tragedy but in the name of a future. Something better for my kids.

Don’t mistake the illegal Mexican immigrant who is, today, working the lettuce fields around Santa Maria, Salinas, Arroyo Grande and Oxnard with an intensity that you might mistake as resignation. It’s the reverse.

In one way or another every immigrant since the Ice Bridge has lived this same story. We are a country of Immigrants and should be proud of it. There is no other country on earth that has the same collective experience. Immigrants are truly the Glory of our Country. We need to be reminded of that often, especially now.

Maria y Jennifer San Salvador, 15 y 17 anos. Students at Oxnard HS. 2020. Oxnard California. Photo: Elizabeth Aguilera for CalMatters, 2020

Si Se Puede.

The hoe, ”El Cortito,” The Short one. One bracero called the hoe an “instrument of horror . . . designed by the devil.” Many growers believed short-handled hoes made workers more careful and kept crops from being damaged. The bosses also liked the short-handled hoe because they could tell at a glance whether the farm laborers were working or resting. After numerous and very contentious lawsuits the hoe was outlawed in California in 1972. The crops, workers and farmers are just fine without it.

Michael Shannon is a writer and died in he wool farm boy. He has an intimate acquaintance with the short hoe. He lives in California.

The Hogger

Chapter Two

Michael Shannon

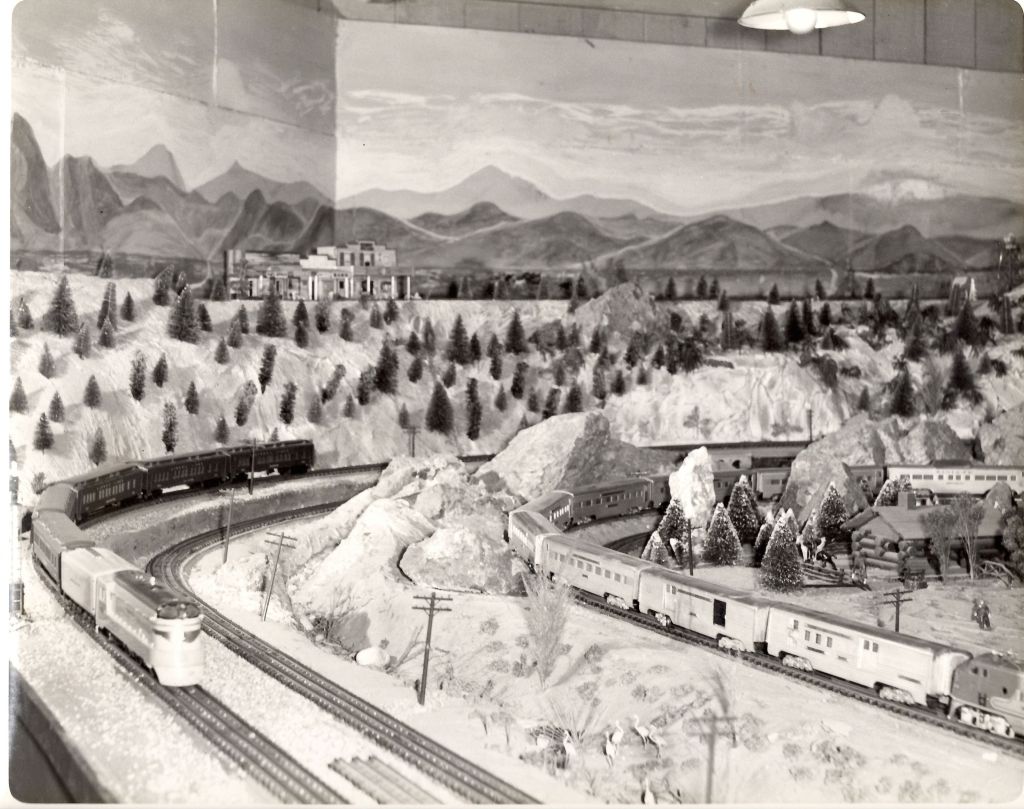

Jack was a clever man so as he packed up the rolling stock and his village, carefully placing each piece in one of the old milk crates stamped with the family’s label, Hillcrest Farms Dairy. As was his nature, being a man who does nothing half way he began to ruminate on how he could continue his railroading.

After running the dairy for thirty years my grandfather was retired. No more 4:30 am cow calls, no more bottling, no more deliveries, he had time on his hands for the first time in his life. At 70, his “ready to go” nature needed an outlet.

The old dairy barn was semi- abandoned, the milk cows were gone and to boot, there was the huge stack of clear heart redwood planking that was left from the collapse of the main silo many years before. An idea was germinated. Why not just move his trains up to the barn? It had electricity, overhead lights and an attached workshop where he could tinker as much as he wanted. What my grandmother thought of this we don’t know but she could hardly have failed to see that it would get him out of the house. After forty six years of marriage, outside was where she was used to him being. She offered no argument.

There is a thing about small towns that many don’t know or remember. Small numbers means that neighbors are, well, neighborly. The glue that holds them together is an unwritten law that precludes people who are acquaintances mind some of their own business. Much depends on that. The grocer and the butcher and their wives and children are people you know. The school teacher, the farmer, the hotelkeeper and the constable are all on a first name basis. You can apply the Mark Twain saying, “A lie travels right round the world while the truth is still getting its shoes on.” People are careful with gossip. It’s someone you know. Everyone needs something from someone else.

It’s not as if normal human behavior is somehow missing in small communities. There is a man who is the love child of two seemingly ordinary people, both married. The state representative is having an affair with the woman down the street. A woman on Nelson St was referred to as a “Sexaholic” by my mother. There is a dairyman who waters his milk and the county treasurer is about to go on trial for embezzling. There is racism, Whites, Japanese, Filipino, Portuguese, Mexican get along in public but there are things said in the privacy of kitchens that prove otherwise.The elders in my family surely knew of these things, yet kept those discussions inside the home and certainly never in front of children.

Going to a small rural school where all these people were represented never seemed to be an issue. Racism is taught. If you are not taught you’ll be happier.

Keeping the lid on the kettle was important to most folks since people not only knew other people but likely knew their antecedents too. When a man like Jack needed help he could get it. Personal relations was the glue that kept communities together.

L-R, George Burt, Jack Shannon, unidentified, George Shannon and Clem Lambert. Family Photo

In the dairy business you needed labor year round from boys and young men who were children of people they knew. When I was a young man I knew many adults who would invariably say, “I worked for your grandparents when I was a boy.” They were full of high praise for the way they were treated. The bus driver who drove me to high school was one. His name was Al Huebner and he had worked haying for my grandfather. There was Clem Lambert, a mechanic, George Burt, builder and Mayor, Deril Waiters, an electrician and builder, Addison Woods, another contractor and many others who had cut their teeth in the hay fields or the milking barn before the war. When you talked to them they would remark that what they got was worth repayment. Pass it forward to a new generation. I worked for some of them because of him. Jack and Annie had banked, if you will, a heap of good relations that they could now call on for his railroad.

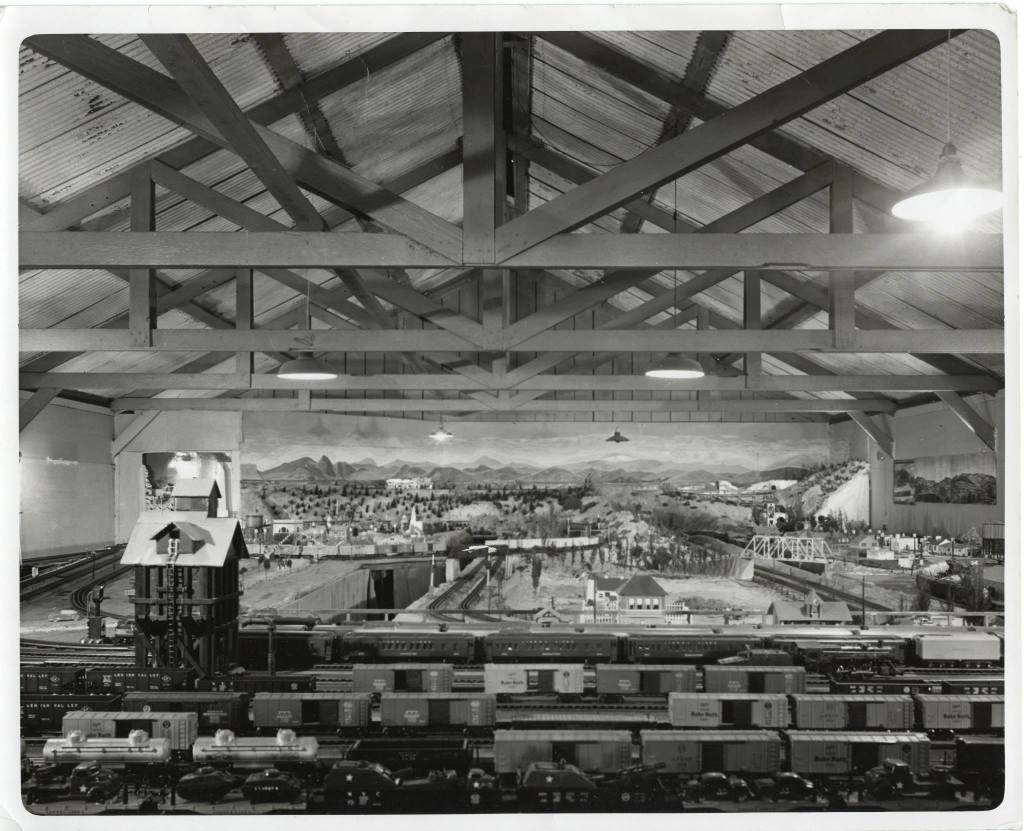

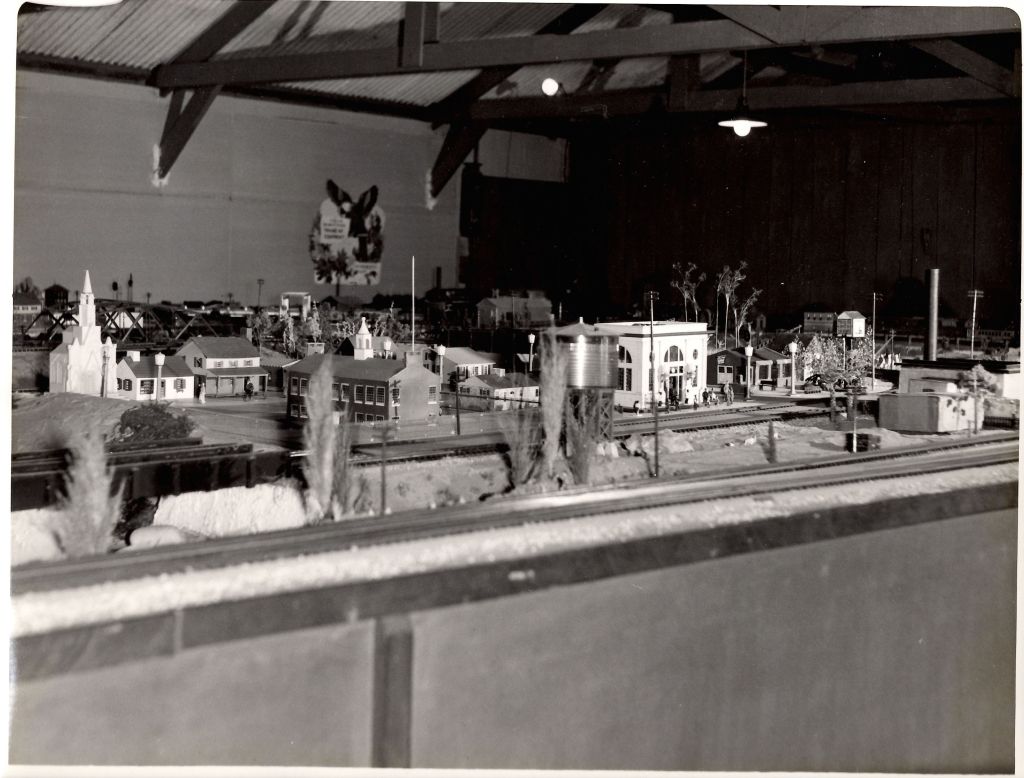

A plan was made. The old cow barn would be the place where his trains ran. The girls were all gone so the barn was empty and just needed a little work to be ready. All the stanchions were torn out. A load of sheetrock was ordered from Leo Brisco’s lumber yard and they covered all the windows and walls to give the interior an nice clean, white surface. They then took all the redwood from the old silo and built a table that covered nearly the entire interior, leaving just a walkway around three sides. My mother came in with her paint brushes and painted a backdrop at the one end.

The Hiawatha and the Super Chief under the big sky. Family Photo.

Deril Waiters helped my grandfather lay out all the electrical wire needed for the switches, building lights and interior lights in the little town with it’s church, hardware store and tiny little homes. All of that was connected to a myriad of switches, toggles and the transformers which would run the trains. The men built chicken wire mountains and plastered them. They built hills, gullies and rivers too. My mother painted and painted. Grandfather built a round house. I thought it was funny because he used toilet paper rolls for the many chimneys on the roof, each one designed to collect the exhaust of the locomotive below. He built a turntable and even stuck a little enameled worker at one end to operate it when a locomotive needed to be run in or out.

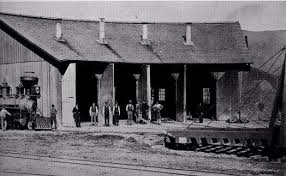

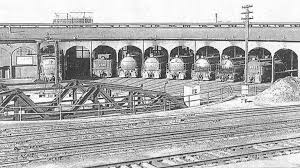

Pacific Coast Railroad and Southern Pacific Roundhouses San Luis Obispo, California

We knew roundhouses. San Luis Obispo was a division point on the Southern Pacific and had a large one along with the shops needed to maintain all the rolling stock. He knew that things were rapidly changing and the big roundhouse would soon be gone so he took me one a road trip to see it. We also plowed through the weeds to see the ruins of the old Pacific Coast railroad yard down on lower Higuera Street. Long abandoned, the shops and warehouse were just the kind of things to tempt a little boy no matter his age.

Apparently this was a family thing because my dad took us on trips to see things that would soon be gone forever. We rode the last ferries across San Francisco Bay, we stood next to the huge Big Boy locomotives as they watered at the little station at Madeline up in Lassen county. My parents friends lived on a ranch there that belonged to Tommy and Billie Swigert. The RR stop was just up the ranch road. When you’re barely four feet tall those engines are monsters. In those days the engineer let kids walk right up to them and touch.

Southern Pacific’s Alco 4-8-8-4 “Big Boy” at Madeline, Lassen County, California. Barbara Shannon Photo.

We went down to Guadalupe to see the great train wreck. A diesel unit pulling freight passing through the Guadalupe yards clipped the rear of the tender on a cab forward 4-8-8–2 Southern Pacific cab forward locomotive and made a huge mess. My grandfather drove me down in his big green Cadillac Sedan Deville and we simply walked through the site. There was train debris everywhere. Trucks with their great steel wheels, journal boxes bleeding grease, Boxcars split by giant can openers, Barrels and crates strewn about, steel rails twisted, ties tore apart already pushed into piles by bulldozers. the Diesel unit’s cab crushed and on its side, the steam locomotive the same. Huge railroad cranes hooking up to the rolling stock in order to lift them free of the tracks. No one seemed to notice us, a grandfather and his little grandson wandering across a train wreck site. Maybe it was the suit he wore or the Caddie, he looked important so he must have been. Afterwards we went for ice cream.

The Southern Pacific Railroad sponsored train rides for many years. Cub Scouts, 4-H and many local school kids took the short ride up the Cuesta courtesy of the Railroad. My grammar school, Branch Elementary would, a few years later, take the last steam locomotive ride up over the Cuesta grade to Santa Margarita. A picnic at Cuesta Park afterwards and the ride home in our mothers cars. The last steamers were then retired and the Diesel-Electric took center stage. Parents and teachers told us about “The Last Thing.” but it doesn’t register when you are so young which in a way is a sad thing. We should have been able to savor the experience when it was happening. Perhaps my grandfather felt the same way. He was born a horse and buggy man when serious travel was by train. For him, those were all the past.

Work on the trains moved along. They built the table from the old silo’s redwood. Removable plywood skirts were added which could be removed in order to work underneath the table. 4 oz duck was glued to the table top just as it was for the mountains. paint was brushed on, trees and vegetation glued into place and fake water filled all the streams and rivers. Many of the houses, autos and trucks were simply bought at the dime store.

I don’t think my grandfather ever attacked anything as a casual endeavor. The family observation was that when he “Made hay, he made hay.” I grew up hearing this and I believed it then as I do now.

Dad would go out to help on Sundays, the farmers only day off, and give us reports at dinner. Occasionally my grandfather would drive out to our farm, pull his big car into the back yard gate and come into the house with a big box of donuts from Carlock’s bakery. He would be peppered with questions by his grandsons and was happy to give us detailed answers though how much of that sunk in I don’t know. It was exciting though. It was hard to imagine even with my little train set chugging round and round on our living room floor circling my mothers hand made braided rug.

After months of anticipation Dad took us out to see the completed project. He parked by the geraniums planted next to the big silo, painted a pink tone, a mix of barn red and white because as was the custom on our ranches nothing was ever wasted if anyone thought it might have some future use. At the top were the faded letters that spelled Hillcrest Farms which were once bright and clear but now after the wars rationing of paint, slipping away. Those years saw the gradual end of local dairies because the big Knudsen Dairy Company had moved into Santa Maria and started buying up the locals, in effect forcing them out. They would all be gone by the mid fifties, so why waste paint?

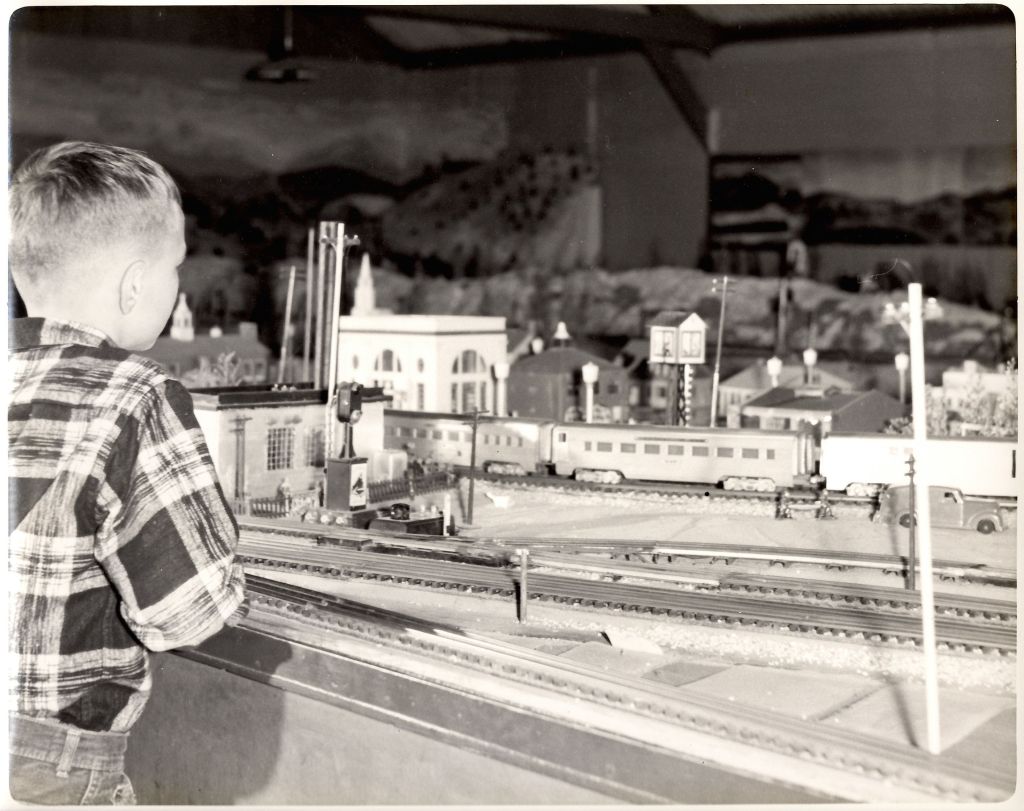

The great rolling door to the dairy barn was pulled back and we scampered up the steps, my dad lifting my little brother because his legs were still too short to do it on his own we entered the cool dark space. My grandfather flipped the old porcelain light switch which made a crisp snap and all the hanging lights came to life. And there it was. What a glorious sight for a little boy. I had, for my pleasure, the largest privately owned “O” gauge train set in the state of California.

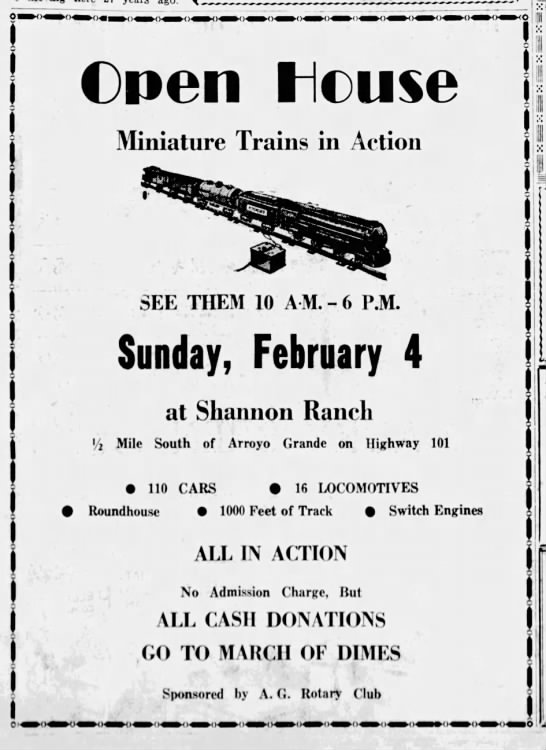

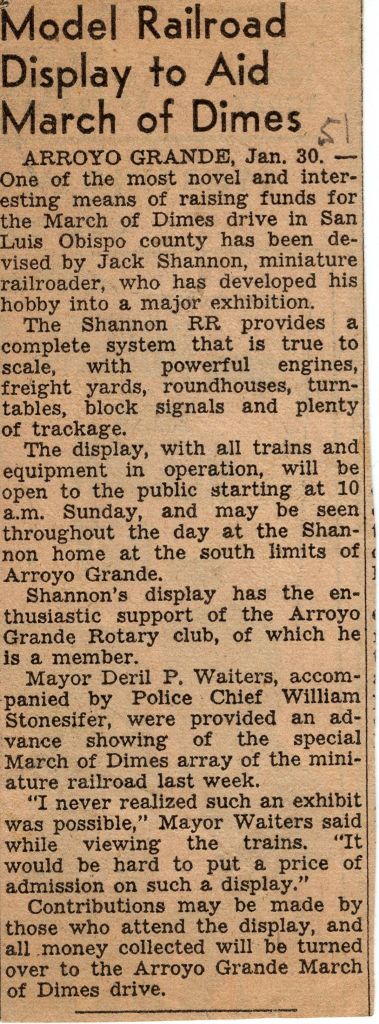

There are those who still remember coming out to the ranch for the March of Dimes fundraisers in the fifties. Sponsored by the Rotary Club, my grandfather a member, the lines would literally stretch out the door with people and their kids. Over the years it was occasionally open to the public and was viewed by thousands of local kids. Much to their delight for those that remember it. Arroyo Grande was still awfully rural then and kids were pretty limited in possible experience.

Sad to say, my grandfather, by now pushing seventy five found it hard to maintain, old barns are not very clean and dust and chaff from the corrals deposited a layer of dust that had to be continually cleaned. Toy trains still used steel rails then and the cracks in the walls and around the doors allowed in enough moisture to continually coat the yards and yards of rail with a fine coast of rust which had to be ground off by hand using a block of pumice. Without good electrical contact the locomotives simply would not run. The hours I spent crawling around grinding away with my stone weren’t that much fun but there was no one else who could do it. The compensation was, of course, learning to operate several trains at once, switch boxcars in the yards and best of all spending a lot of time with my grandfather.

Dad would take me out in the morning after breakfast and drop me off at the barn where I did my track maintenance until noon. Jack would bundle me into the big Caddie and it would make its stately was along the highway frontage road and up the hill the house, where my grandmother would have a lunch laid out for us, baloney sandwiches with Mayo and the cold, cold milk she kept in the yellow Fiestaware jug she kept in the fridge. I felt very grown up when my grandfather offered me “A Cuppa Jo” which I accepted just as if I was all grown up. Boiled on the stove he and my grandfather would take theirs poured onto a saucer from the cup and mine would be liberally laced with sugar and milk. What a treat. Afterwards a little nap and then the return trip.

I’d earned my engineers license in the morning and we would spend some time at the bank of big black Bakelite transformers driving the New York Central’s Hiawatha and the Southern Pacific Daylight passenger trains around and around. We ran the little Yard Goats, making up freight trains, parking under the coal chute and moving locomotives in and out of the round houses. We could wind the key in the little church and the bells would call to service. In the corner was an old record player and grandpa would put on a record that played the sounds of passing trains and the heavy staccato exhaust of the big locomotive starting a train. He taught me how to synchronize the sound with the little trains on the layout. He said it had to be just right. There was no speeding or crashing of trains. Everything had to be just right. It was not apparent to me at the time but lessons were being learned about hard work, rewards and all things proper.

Years later when I returned to Arroyo Grande from my own adventures, both my grandparents had gone to heaven. I went out to the barn and opened the door and viewed the forlorn table, cleared of all the trains and track. Only the hole where the round house turntable once was, was left. The mural my mother painted on the back wall was a fresh as ever. Nothing, really, was left. It had all been sold years before, my grandfather just gotten too old and let it all go. All a memory now.

You can’t imagine how that felt to the grown man who cherished the little boy and his grandparents.

The Jack Shannon Railroad 1953. Family Photo.

Jack Shannon lived to be 96 years old. A long and busy life. He was born in 1882 in frontier Reno, Nevada, and grew up in Arroyo Grande California. His life spanned from the horse to a man on the moon. Just marvelous don’t you think?

Linked to Chapter one. https://wordpress.com/post/atthetable2015.com/12395

Michael Shannon lives in Arroyo Grande, California.

The Hogger

CHAPTER ONE

By Michael Shannon

Hogger is a slang term for a locomotive engineer. Steam locomotives were referred to as “Hogs” in the early days of railroading.

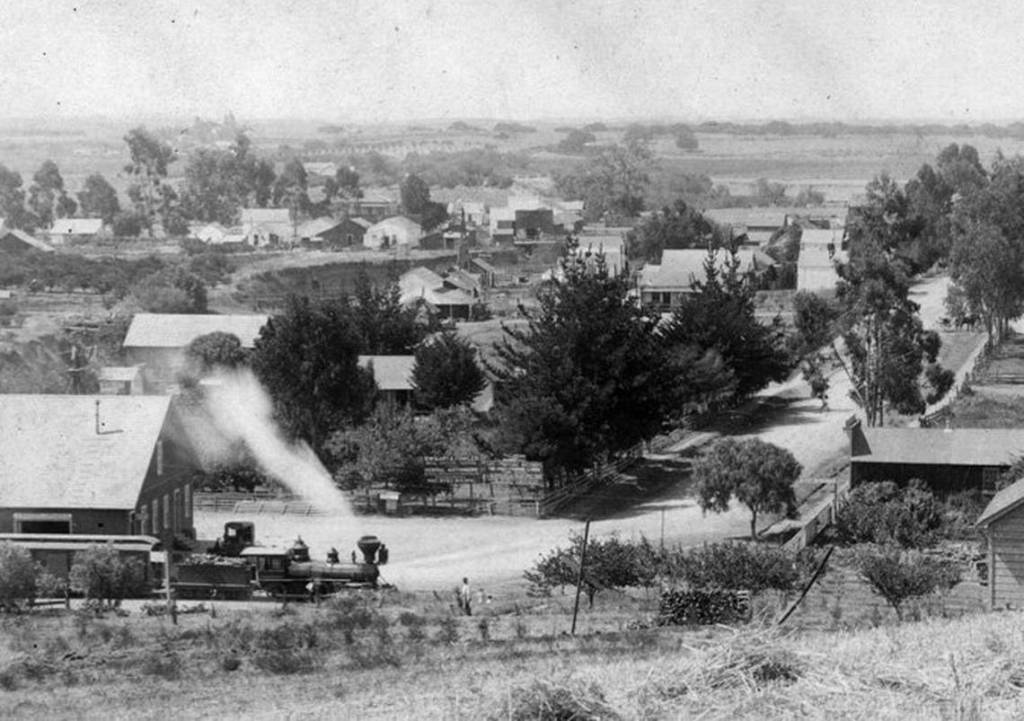

My grandparents grew up when trains were the most modern form of transportation. When they were children growing up in Arroyo Grande, the steam train dominated the movement of people and goods throughout California’s Cow Counties. The big Railroad, the Southern Pacific hadn’t arrived yet, there was a promise it would but it took years for the local movers and shakers to pony up the bribes and free land that the Big Four demanded. No, the railroad here was the little narrow gauge Pacific Coast. Quite a bit smaller than the big train, it had served the area since 1868. It ran essentially from nowhere to nowhere. It huffed and puffed its little self-confident way to and fro making no apologies to anyone.

Arroyo Grande station and warehouse 1898. Historic Society.

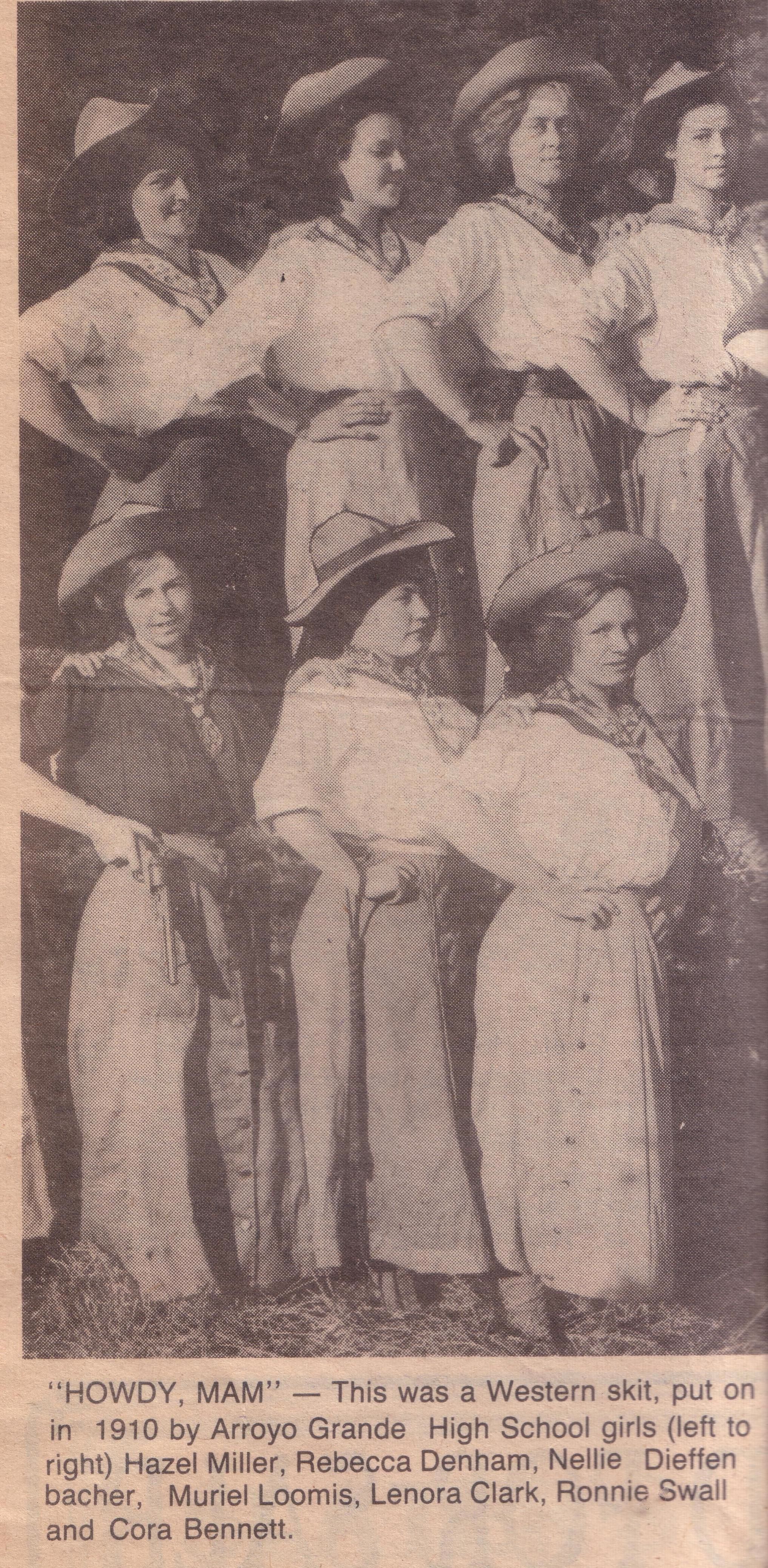

My grandmother Annie rode it down to Santa Maria to go to High School. The high school in Arroyo Grande wasn’t accredited for those that were planning on going to Cal Berkeley. She and her friends hopped aboard, the train would actually pick you up in front of your house, to take trips up to San Luis Obispo to shop for the latest spring frocks and hats.

Nearly all the goods in the stores that marched along Branch street had to have their merchandise brought down from San Francisco by steam or sail and then shipped by rail to their destinations. The largest building in town was the PC warehouse on upper Branch Street.

Pacific Coast Railway Bridge Arroyo Grande, Ca, 1914. County Historical Society.

When my grandparent were kids the only bridges across Arroyo Grande creek were the railroad bridge and Newt Short’s swinging bridge which was only good for pedestrians. The RR bridge handled most of the walking public and all the wagons crossing the creek. It also served as an impromptu gallows at least once.

If you lived in town to train whistle and the rumble of the cars was a daily fact. My grandfather lived with the sound of that little train for almost fifty years. It’s no wonder it was planted in his thoughts.

Dad Shannon’s little house on the dairy. Family Photo

Christmas eve 1953 the family jumped in the green Buick sedan for the trip to my grandparents house where we always spent Christmas eve. It’s impossible to recall the excitment little kids feel when you are grown. Anticipation can cause you to almost wet your pants, your hair to stand on end and your head spin. The cars in those days had fabric upholstery which had a singular odor mixed with cigarette smoke and the ever present dirt and dust that farm families live with. Once in a while the car got washed but it was a fruitless exercise for my mother. Its pea soup color was always dusty in summer and muddy in winter. No matter how it looked it might as well been a golden chariot on Christmas eve with three little boys bouncing around on the seats in a collective fit of anticipation. Kids didn’t get many presents in those days. One special thing and the rest was basically utility. Shirts made by my mother probably, always socks from bachelor uncle Jack who didn’t have a clue. I got socks from him every Christmas for nearly fifty years. We really weren’t concerned about quantity. We had heard stories about Christmas past when my father got a pair of socks knitted by my aunt Sadie and a fresh Orange. He told me he was glad to get them too, especially the Orange, a pretty rare thing for those days. That was in 1920 when he was eight and he still operated on that principle in the fifties. Things were not particularly important to him. He felt that you should be grateful for what you got and say thank you because no matter what it was it was important to the one who gave it to you. The thing had no particular value, it was the love that counted.

When you know you will only receive one gift, why, it takes on a much greater importance. It was a good lesson.

We drove into town and then south on the old highway and turned off on El Campo Road where my grandparents lived on their ranch. The little red house with the white trim was down in a place I always thought of as the hole. The big bank of the highway and the old Nipomo road on the other side boxed it in and you entered downhill on the gravel driveway. Built n 1924 by my great-grandfather it was a simple board and batt sided, two bedroom with a door at each end. The backdoor led into a screen porch where grandmas pie safe stood, green with screen in the doors that looked like lace. Full of jelly jars with room for a cooling pie. There was a bench for changing shoes and some hooks screwed to the wall to hang jackets and hats on. In 1953 every man still wore one. Open the inside door and you were in the kitchen. Very simple it was. Next the dining kitchen table area and then through to the living room. Behind that was the front door enclosed in a little add on porch. This door was nearly useless because no one was ever likely to use it. Only itinerant drummers like the Fuller Brush man or his like. The custom in the country is to always use the back door. There is a familiarity and friendship involved in that like you might almost be a member of the family. Even the Knights of the Road knew this, they would come down the hill from the highway, tap on the door and stand with bowed head and hat in hand. They were not turned away. It was a vastly different time.

I only went in that front door a few times in my life, always on Christmas eve. My grandparents built a new home in 1954 up on the hill. A modern style home, yes, but we still used the back door except at Christmas .

Christmas 1949. Annie Shannon, my father and two of his boys just arrived at the old house. Family Photo.

1954, in what was our last Christmas in the old house in which the event that is the subject of this story occurred. We heaved the doors to the Buick open and ran to the door hoping to catch Santa in the act but as seemed to happen every year he had just left by the back door while we tumbled in the front. Mom and dad followed, arms full of presents, Cayce, my little brother, just three dragging mom by the hand squeaking in delight.

Grandma and grandpa met us at the door she in her print dress, sturdy shoes, old fashioned wire rim glasses and her apron, always with a hanky peeking from the pocket. She smelled sweetly of white shoulders and when you hugged her she would give you her very soft cheek to kiss. The formal and manly handshake from Big Jack as he uttered his, “The Blessed Boys,” with that big grin, his chest pushed out and his green suspenders like two vertical stripes holding his belly in. Uncle Jackie bringing up the rear, short, bald and bandy legged he sported a big grin, delighted to see his nephews. This ritual of greeting never changed as long as they lived, it didn’t matter if they had just seen you an hour earlier it was always the same.

In that last Christmas in the old house, the biggest most important thing for me was a brand new Lionel electric train. The little black engine pulling the cars and caboose in a stately manner around the Christmas tree. My grandfather got right down on the floor with me and we played with it until dinner was called. I could hardly step away. Eventually, full of turkey and homemade pie my brother Jerry and I fell asleep on the floor. Mom cuddled with little Cayce on the sofa until it was time to go home. The little train set stayed until dad could go back with the pickup to get it.

My dad visited his parents often. Sunday, which was a no work day would see him sitting at the green painted table with the checkered oilcloth cover, tacks along the edge to hold it in place. This was the kitchen of the old house where he had grown up. They would drink scalding hot coffee from the old enamel pot that sat in its habitual place on the stove. They’d be shooting the breeze, his parents and brother Jackie. They had nearly fifty years together so there was always something talk about.

After one of these visits, sometime after new years he came home and over lunch laughingly told us that after Christmas my grandfather had gone to Bello’s store in San Luis Obispo and bought himself a train set. My grandmother thought it was pretty silly for a grown man to do that. It was a silly little topic at her bridge club. Mrs. Brisco, Mrs Conrow and Mrs Jatta agreed and commented that it was just like Jack to do something like that. They said he was still just a boy at heart. They spoke the truth.

The little train lived in their living room for a bit but slowly began to grow. He added track, some trees and two small buildings. One was a church that looked similar to the one my grandmother attended. Perhaps this was an attempt to head of the inevitable grandmother “Stink eye” that was sure to come when the railroad would need to be moved for company.

By mid-January he made a trip north to buy more track, though he was already encroaching on the dining area. The next day grandma went to town to do her shopping and run some errands and when she came home he came out to help her unload the food she bought at Bennett’s grocery while she went in the house to take off her hat and gloves and put on her apron to ready supper. From outside Jack heard her raise her voice to the high heavens and quickly the sound of her voice saying, “Jack, you get in the house right this minute.”

He had finally reached her limit for what he had done with his new track was cut three holes in the walls so the train could pass through into the bedroom, make a left turn through another tunnel into the office and then turn again through the wall back from where it came. Enough was enough. She evicted him and his railroad.

Jack and Annie Shannon circa 1950. Shannon Family Photo.

Jach was a clever man so as he packed up the rolling stock and his village, carefully placing each piece in some of his old milk crates stamped with the family’s label, Hillcrest Farms Dairy. As was his nature, being a man who does nothing half way, he began to ruminate on how he could continue his railroading…….

Part two is coming on Saturday the 8th of June.

Michael Shannon is a born and raised Californian and still lives in God’s country.

THE TWELVE O’CLOCK KID.

By Michael Shannon

A hilarious look at how kids spent their nights in the days before play dates, day camp, and structured activities, “Whacha Wanna Do?” This story captures a world gone by that will be a revelation to younger readers and an affectionate look back for those families who remember the old stories.

He was a twelve o’clock kid in a nine o’clock world. He was a teen aged boy at the last gasp of the nineteenth century. His name was Jack. He ran the dirt streets of Arroyo Grande with his boys, Ace Porter, Matt Swall, and Arch Beckett, whose flaming red hair could be seen from a mile off.

A little farm town, Arroyo Grande was named for the narrow valley that runs from the Santa Lucia mountains to the Pacific ocean. In the 1890’s there weren’t many of the things we consider necessities today. No sidewalks, street lights, or pavement. The horse was king. No automobile had yet to show itself up in the Cow Counties. There was a tiny Railroad, the Pacific Coast but it ended at both ends without really going anywhere. The stagecoach still made regular stops in front of Ryan’s Hotel on Branch Street. It was lights out at nine o’clock.

Whatever you wanted had to come by wagon, coastal steamer or sail ships which regularly docked at the wharf in Port Harford. By road it came from the South, over the San Marcos road at Slippery Rock or very carefully down the old toll road over La Cuesta from the north.

In those old days there was a lot of time to fill. Early to bed, early to rise, neither one particularly appealing to teen boys. As always the best deeds are done at night.

Jack was thirteen in 1895. He was on the cusp of manhood. His country was too. It was about to go from a century of rather slow progress to one moving at almost blinding speed. Eighteen ninety-five was quite a year to be alive in the world. It was a time in history when the era that was passing and the era beginning were locked together like the cogs in two wheels, ready to transfer the energy of one to the other. In England Queen Victoria was entering the final stretch of her 63 year reign. Oscar Wilde was at the start of his two year sentence for “gross indecency” in Reading Gaol. The first professional football game was played in Latrobe, Pennsylvania. In the fall, George B. Selden is granted the first U.S. patent for an automobile. Meanwhile, William Randolph Hearst, the young heir to his fathers silver-mining fortune whose father, a United States Senator had recently given him a small San Francisco newspaper to run, made the seemingly foolish move of buying a failing New York newspaper, the New York Morning Journal. It was the start of multimedia empire that would expand to over thirty papers and change the face of journalism.

This was the year that Guglielmo Marconi, a twenty one year old Italian and scientific hobbyist first succeeded in transmitting radio waves over a considerable distance. It would soon make possible wireless telegraph and eventually, broadcast radio and the internet. In Charlestown Massachusetts the first black man to earn a PhD graduated from Harvard. He was W. E. B. Du Bois. A Neurologist in Vienna woke from a strange dream about a patient and decided to develop a method of analysis of the interpretation of dreams including his own.

In that year, almost every segment of American life was on the brink of a disorienting transformation. Technology, Entertainment, Transportation, Education,Labor practices, Social and sexual behavior, Race relations and Parenting all entering a time of profound change. The way people spent time with one another and interacted with the world around them was about to be overrun by a series of dizzying events.

Few people in America could have been further removed from the social, technological and cultural change than the citizens of little Arroyo Grande, it’s population, less than four hundred people and isolated in a corner of California much as it had been for the six decades since its founding as a Mexican land grant in 1835.

Jack and his parents, John and Catherine had made the slide west from Reno Nevada where they operated the Toronto house restaurant and a boarding house called the Ohio House. Located near the river on Virginia Street is was a busy and popular place and why they sold out and moved west has been lost, although court records may indicate a certain reluctance to pay their bills.

John Edward Shannon, known in the family as Dad Shannon always listed himself on census forms as a Capitalist, a common term at the time for a promoter and investor. His mother Elizabeth, a widow with seven children ran a tavern in Lackawaxen, Pike County Pennsylvania. John himself worked as a brakeman on the New York Central railroad by the time he was twenty and then spent a year in Sing Sing prison for breaking into and stealing from the boxcars he was working atop. Capitalism at it’s finest, illegal, but what capitalist won’t take a risk.

He dealt in real estate and property and the move to Arroyo Grande included a home and property just east of town where they was in the fruit and egg business. The old house on the slopes of Carpenter Canyon still stands. Jack could simply walk down hill cross the usually dry Becketts Lake and be in town which was just a short diatnace away.

The old house on Printz Road.

Young Jack grew up there in comfortable surroundings, his mother Catherine was a women of some drive and means. Originally from Toronto, Canada and New York, She had owned the Craig house on the waterfront in Oakland and later a hotel in Berkeley. She was a widow when she met Dad Shannon in Reno, the site of her latest endeavor the, Toronto House restaurant and boarding house on Virginia Street, the future site of the famous Mapes Hotel. After the 1875 marriage, he bought the Ohio House, another boarding house so they weren’t poor. They ran the three businesses until 1890 when they sold out and moved to Arroyo Grande. She was 52 and they had decided to retire from their businesses. At 52 she should would have been elderly by the standards of the late nineteenth century.

Jack was the product of her second marriage. She had four other children who were grown and scattered arount the country in San Francisco, Berkeley and in New York. She married Jack’s father when she was already 40 years old and was 47 when he was born. A pretty advanced age to be having children in the eighteen eighties. An afterthought, the bonus child or the accident, we don’t know. The family story is that he wasn’t exactly considered a gift from above. With four grown children she had the experience of motherhood but perhaps not the tender desire if you will. She has come down in family lore as the “Meanest women in the world.” My dad could never explain exactly why as he was just a little boy when she passed away. He did say they were both pretty heavy handed with punishment. Jack was very well acquainted with his father’s razor strop.

Strops are unusual today but back in Jack’s day men used a straight razor to shave and after honing the edge on a wet stone a leather strop, usually made of heavy tanned cowhide with a hook or ring on one end and a leather handle on the other. The ring would be placed on a wall mounted hook and the strop pulled taut by the handle. The razor was then dragged back across the two foot long strop which removed any burrs on the edge of the sharpened razor’s blade putting on a very fine edge. The strop was also very useful in tanning a boys hide. Jack and his father were both very familiar with this use, one on each end. Jack never seemed to hold corporal punishment against his father. It’s difficult to complain against that which is richly deserved. Didn’t slow him down, just reinforced his desire to “Get Outta Dodge” as the old saying goes. In his teens Jack put a lot of thought and energy into running away from home though he was never really successful.

Growing up in Arroyo Grande it didn’t take Jack long to display his rambunctious spirit. Boys in the 80’s and 90’s lived a quite different world than we did just two generations later. The idea that children were essentially owned by their parents was still the norm. As a form of legal property, they had no real rights as we know them today. Parents could put them to work at almost any age and they did. Boys delivered newspapers, cleaned spittoons in the many saloons on Branch street. The yworked in the butcher shops, they delivered groceries from Bennett’s store. The mucked out the stalls at the Harloe stables and tended the forge at Miller’s blacksmith shop down on the creek. If you needed windows cleaned there was a boy. Because most boys, rarely if ever were required to go to school there was always one handy.

Kids were allowed to roam freely, a circumstance that still applied when I was young. There were no tresspassing signs as property owners knew which kids belonged to which family so someone almost always had an eye on you. Fishing or swimming in the creek, riding your bicycle to San Luis Obispo, going varmint hunting with your .22 or simply disappearing for hours at a time were common activities. A boys time was his own, at least when he had some.

My grandfather when I knew him was always quick with a joke and loved to tell stories about his young life. It wasn’t hard to see the rambunctious mischief maker in the man. He wasn’t afraid to be the butt of the story either which game him a certain verisimilitude which was charming for for us kids. He could laugh at himself.

If you asked Jack if he was ready he’d say. ” When I get up every morning.”

That “Always Ready” was for a time a bit of a problem. The term “Lets Go” never found a more willing participant. His running mate Ace Porter, he of the cheeky grin were best friends for life.They met as altar boys you know. They were the quintessential example of the scapegrace’s who got into the sacramental wine, switched Holy Water with water from the tap and tied knots in the bell rope.

Saint Patricks Catholic Church 1890. Photo: Marshalek Family

They were well known for their pranks by Father Michael Francis Lynch, the pastor of Saint Patrick’s Church. Father Lynch, bless his heart, must have been a good soul. Both of them had earned their reputations for being mischievous tricksters. It didn’t end in church either.

On All Hallows Eve, Jack climbed over the window sill after his parents had gone to bed and met his cohorts down to Miller’s blacksmith shop right along the creek. Just behind the Meherin store, it was right up against the willows which lined the Arroyo Grande creek. The willows, Sycamore trees and the huge stands of late season Poison Oak provided cover from the town constable Thomas “Tom” Whitely, who was prowling the little town looking for scapegraces up to no good.

Whitely would have know about scapegraces. He had been roundly criticized for doing nothing to stop the lynching of the two Hemmi men from the railroad bridge in 1886. One of the men was actually a fifteen year old boy. Newspapers around California were scathing in their criticism of Whitely and the uncivilized citizens of Arroyo Grande who did the deed. They being the town’s most prominent men. No one was ever named nor arrested for what amounted to pre-meditated murder. In a small town where there were many family ties and everyone knew everyones business, silence on the matter stated the consensus verdict.

Whitely was also called before the Grand Jury to explain why he had continuously failed to remit the entire amount of the fines he leveled and the bail collected to the county treasurer. He fought the case and lost. In 1900 the voting citizens of Arroyo Grande sent him packing in favor of Frank Swigert.

Hunting boys intent on mischief must have been a lark for him as it likely entailed no risk. In fact, people whose gates were lifted and hidden or outhouse pushed back just a few feet exposing the cess pit to the unwary man stumbling through the dark half asleep would be thankful for the constables diligence.

This didn’t deter Jack and his gang for on this night, they had bigger things in mind. A notable prank that would give early risers a start as they came up Branch Street to begin the day.

They quietly took a spring wagon parked behind F E Bennett’s store and pulled it up to the Union Hall. Using wrenches and screwdrivers purloined from their fathers sheds the quickly reduced the wagon to its constituent parts. Boosting Jack up to the roof, they began handing up the pieces, the box, seat, springs, dashboard and the wheels. Climbing up, they just as quickly reassembled the wagon astride the ridge of the roof. When the job was complete they shinnied down and headed for home.

The old Union Hall built by Judge Beder Wood, 1880’s. Historical Society.

The next morning Ma Shannon was surprised to see Jack headed out the door much earlier than usual. When she called out . “Where are you going? he answered over his shoulder, “Goin’ fishing.” Not likely, he was headed down to Branch street to meet his fellow outlaws in front of the Commercial Company building to spy out the reaction of folks to their handiwork. Across the street the Hall sported the Studebaker wagon proudly astride the center of the roof. They watched as the early morning crowd gathered. Boys on the way to school larked about laughing, nearly overcome by the audacity of the deed, Beder Wood, the owner of the building talked to the Constable and some other prominent citizens, growling about delinquent youth and how he’d like to take a wack at them. Maybe put them under, he being the towns undertaker. The little boys cast their eyes surreptitiously across the street at Jack and his friends. Knowing looks were exchanged. Someone fetched a ladder and the men began the task of reversing the nights work. Jack and his friends quietly disappeared and the little boy dashed of to school to report the big news.

As the old saying goes, “Success Breeds Success.” The boys went about their regular business while they plotted their next foray into the world of crime. They laid low over the Christmas holidays and the early spring of 1899 but with the coming of All Fools Day the put their next plan of action into play. That year it fell on a Friday which suited the gang perfectly.

They all snuck out of their houses and met behind the Cumberland Presbyterian Church on Bridge Street. There they spied out the vicinity making sure the Constable wasn’t anywhere around. The figured he was likely tossing back a beer at the Capitol Saloon anyway and wasn’t going to be any trouble. They dashed across Bridge Street to the big and imposing Grammar school directly opposite the church. They scouted the building to see if they could find a way inside. They found a conveniently unlatched window on the first floor and quickly boosted each other up, scooted and over the sill. Miss Young, whose room had the unlatched window, suspicious as that in was itself, fit with the plan to do no damage. Once inside they carried out the mischief they had been plotting for weeks.

Arroyo Grande School, Bridge Street, 1899.

They quickly ran up the stairs to the second floor where the upper grades and the high school held their classes. Mrs. Watson’s book shelves were emptied and all the books mixed up and piled at the head of the stairs. Her desk was moved to the opposite end of the room and the desks reversed. Mr.Huston’s room suffered the same fate. His books were piled on the top of the stove, his desk and the floor. The school organ which Mr. Huston played for school presentations was hefted and then slid out to the hallway and placed at the top of the stairs. The organ and the books made a wall blocking the upper stories.

The midnight vandals disappeared the same way they came leaving nary a clue to their identities. Nothing was discovered until the following Monday when the front door was unlocked by the custodian. Frank Parsons, the principal, galvanized every teacher as they came through the door in the clean-up effort. The sound of cast iron school desk legs scraping the floor, books quickly tossed onto shelves and the swish swish of brooms rang out through the building. Frank’s idea was to reverse the joke by having everything in order before students arrived. He figured the vandals would get no satisfaction if the students never found out what had happened.

He was mistaken. The children’s telegraph was operating at full throttle. After the bell they sat in their desks and sniggered when ever they thought the teachers weren’t looking or listening. The teachers knew of course because every one had elephant ears and eyes in the back of their heads. It might have passed unknown, the school wanted to keep the joke quiet but the kids couldn’t wait to get home and share. Because one of those student’s father just happened to publish the town paper the story was memorialized in print. Though Stephen Clevenger may have used a little tongue in check in writing about the great event, I mean how many notable events go on in a small farm town at the turn of the century?

Clevenger wrote, “It was probably funny for the boys engaged in the performance but trustees, teachers and scholars will require the funny part to be pointed out to them before they can see it.” Oh, I don’t think so.

Clevenger wrote, “The boys incurred the grave risk of entering the school building and tampering with its contents.” As a crime it didn’t amount to much and no one was ever brought to task for it by the law.

My grandfather said that punishment was a liberal laying on of the strop, again. Though there was no proof any of the boys was involved, Dad Shannon evidently though that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

It never slowed any of them at all. I mean, whats the use of never taking a chance.

The Meanest Woman in the World, Catherine Brennan Shannon with my uncle Jackie, 1917. Berkeley, Califonia.

He figured he could solve the problem by running away. They caught him pretty quickly. After all the distance between towns in the cow counties is pretty large and what do you do with little or no money, so no stagecoach or railroad, it had to be shanks mare and that was slow going. He tried again though and then again. He finally made it when he turned eighteen because they couldn’t legally stop him. He didn’t fool around either. He headed straight across the country and ended up in New York City. His adventures made for many funny family stories.