A short history of the man bun and the men who wore them.

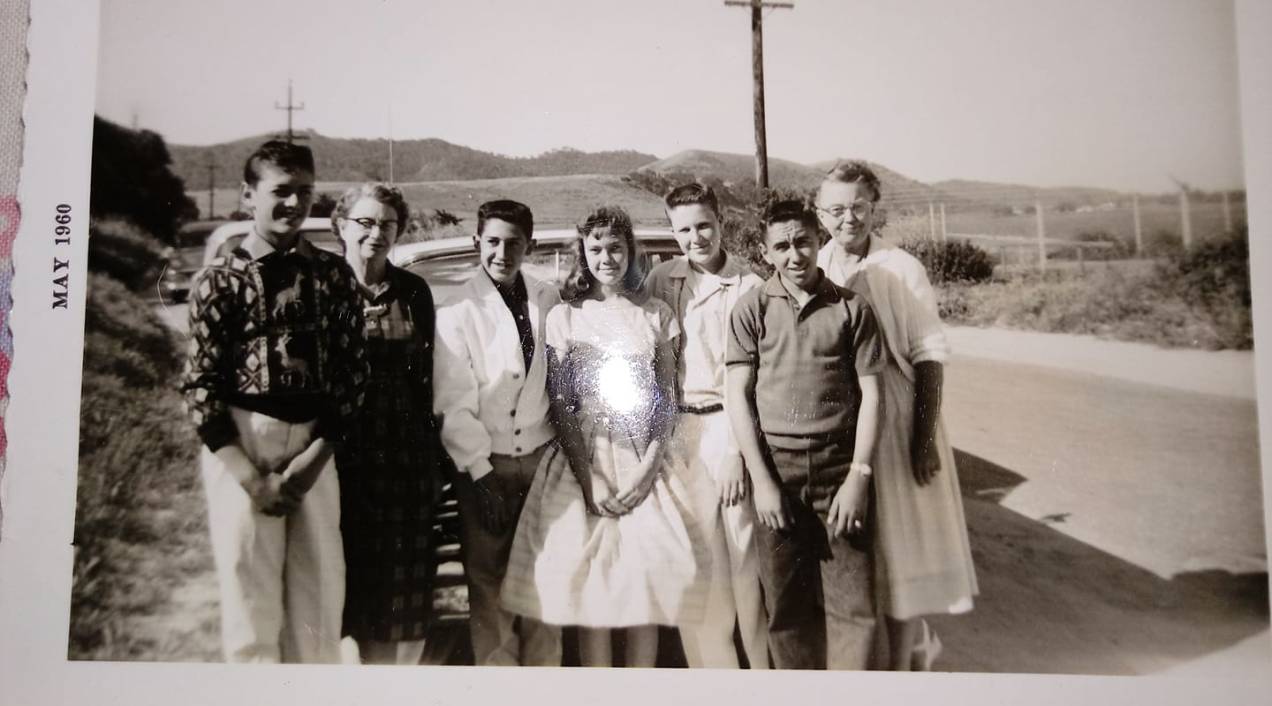

Dedicated to K J Gonzales, Judy Sweaney Hall and John A Silva.

VERCINGENTORIX: BORN: 82 BCE-DIED: 46 BCE

The procession came in sight down the Via Flaminia. The Tribunes marched in the van holding aloft the standards of the Roman Legions who had fought the Gaul in the year 52 BCE. Each standard topped by a golden Eagle with the initials of the Romans, SPQR engraved just below. Paced by trumpeters playing fanfares, followed by the kettle drummers setting the standard military cadence, 120 steps per minute. The mighty Tenth legion, its Imperial Standard glistening in the sunlight, the banner hung below embroidered with a rampaging wild boar and its motto Fretensis. The Legionnaires staring straight ahead, armor polished, skirts swaying in time to the drums led the military. The three other legions, the first, Germanicus, the fifth, Galicia and the fourteenth, with its rampant Sea Goat symbol. All had fought the Gauls across northern Europe and Germany, there were nearly 25,000 men of Romes Finest. Their heavy sandals beating the cobbles in time they marched ahead of the rude cart drawn by captured Alemani chieftains. On the cart, The King Vercingetorix stood, hands and ankles shackled to iron rings in the floor of the cart, his head held erect by cords binding his neck to a post. Centurions flanked the cart carrying his swords and armor. The man who had surrendered to save his people from slaughter had been held in the bowels of the Mamertine prison for six years. Though he was gaunt and pale he held himself erect and looked every bit the warrior King.

Prisoners were held in Mamertine to await execution or were simply allowed to starve to death out of sight. Rome’s vanquished enemies were imprisoned and often died here. Among the famous figures in history who spent their last days here include Vercingetorix, leader of the Gauls, who tried to rally the Gallic tribes into union against Caesar in 52 BC; Simon Bar Jioras, the defender of Jerusalem, who was defeated by Titus in 70 AD, and supposedly, the Apostles Peter and Paul.

Following King Vercingetorix was Julius Caesar himself. Standing in a Golden chariot drawn by four pure white matched horses with harnesses picked out in gold and silver. Behind him, holding aloft a laurel leaf crown was the leader of the Roman senate.

Following Caesar were wagons overflowing with the spoils of war. Swords, spears, armor signified his complete mastery of war. Lastly came the captives, Celts, Gauls, , the Arverni, Atrebates and the Belgii. They were the flower of kingdoms that we now know as France, Germany and parts of Belgium. The defeated Celts fled to Ireland where they live today, very few of the true Gauls survived and those mostly slaves to the Romans or sold around the Mediterranean..

When the procession reached the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, Vercingetorix was cast loose from the post and led inside the temple and before the priests of Jupiter and Julius Caeser was forced to kneel before the altar. At Caesars order his arms were held by Centurions, a third held his bun and a cord was dropped over his head and he was strangled to death. Such was the triumph of Caesar.

An honorable man, the king had surrendered to Caesar in order to spare his people from massacre. Caesar massacred the people anyway. Vercingetorix is considered a hero in France and a bronze statue stands at Alise-Sainte-Reine, Burgundy, France.

QUIN SHI HUANGDI: BORN: 259-DIED: 210 BCE

In 1974 peasants digging a well in the drought stricken western Shaanxi province of China unearthed fragments of a clay figure—the first evidence of what would turn out to be one of the greatest archaeological discoveries of modern times. Near the tomb of Qin Shi Huangdi—who had proclaimed himself first emperor of China in 221 B.C.—lay an extraordinary underground treasure: an entire army of life-size terra cotta soldiers and horses, interred for more than 2,000 years. Each one wore a Man Bun. Except for the horse’s of course.

The stupendous find at first seemed to reinforce conventional thinking—that the first emperor had been a relentless warmonger who cared only for military might. As archaeologists have learned during the past decade, however, that assessment was incomplete. Qin Shi Huangdi may have conquered China with his army, but he held it together with a civil administration system that endured for centuries. Among other accomplishments, the emperor standardized weights and measures and introduced a uniform writing script.

The pits are a colossal exercise in government expansion. Like today, they may have been designed to glorify Qui Shin, the emperor and power of his reign. The idea that government builds in order to glorify itself and its beliefs was just as common in the third century as it is today.

With an estimated 7,00 t0 9,000 soldiers excavated so far it is telling that as far as science has been able to determine, each and every figure is unique and was likely copied from a living man. Think of it. Nine thousand unique individuals who lived 2,2040 years ago, each wearing a Man Bun.

ATILLA: BORN: 395 AD-DIED: 453 AD

Storming out of the vast plain of Hungary the Hunnic armies pushed the Germanic tribes west into the plains of France in the fifth century. Led by their hereditary ruler Attila, seen above with his Man Bun they rampaged and slaughtered their way across Europe and down into the middle east. Exploiting a new development in warfare, the deployment of armies disposed of nearly all cavalry. the Hun horsemen carrying the very powerful recurve bow that allowed them to strike from horseback creating a mobile force difficult for foot soldiers to attack. Attila and his brother Bleda campaigned down from Bulgaria, chasing the eastern Roman armies through western Turkiye, Thrace and decisively defeating them at Gallipoli. Rome effectively became a vassal state paying tribute to the Huns. In succeeding years, in order to protect themselves, both the eastern and western Roman empires employed the Huns as Mercenary armies to protect what was left of the empire from other aggressive cultures. This, of course, let the fox into the henhouse. Descendants of Attila figured that, why work for the Romans when you have the power to rule them, which is what they did. Perhaps the Romans ultimately wore their hair wrong. Roman leaders wore their hair short and combed from back to front. Who’s to say.

CHINGGIS KHAGAN: BORN:1162 AD-DIED:1227 AD

The Great Khagan’s military successes made him the greatest conqueror in history. By the time of his death, the Mongol Empire occupied modern day Russia including Kiev and Moscow, all of China, Korea, Southeast Asia, India, the Middle East, Turkey, and as far west as the Danube River. His sons and Grandson expanded the empire ultimately reaching the city walls of Vienna.

As simple as it may seem a simple invention led to the primacy of the Mongol warriors success. Being a plains culture, entirely dependent on the horse or more accurately ponies, they roamed the Mongolian Steppes as nomads. The horse were small, the better to survive in the harsh conditions of the high wind swept plains of central Asia. The horses ate no grain and were entirely feed on grasses and surprisingly, goats milk. Goats milk was the foundation of the Mongol diet and ponies were no exception. Soldiers put meat under their saddles to tenderize it and when they had no water they would carefully puncture a vein in their horses neck and drink the blood. Some of the Khagans armies numbered over one hundred thousand warriors and riding day and night they covered great distances to the surprise of their enemies. The horsemen themselves used the invention of the stirrup and the wooden saddle tree to great advantage. They could turn their small horses on a dime and use their feet in the stirrups to gain thrust when using spears and Javelins. Their prime weapon, the composite bow could be fired in any direction while the fighter stood in the stirrups.

Chinggis practiced war on a brutal scale. Surrendered armies saw their soldiers executed by beheading, All citizens were forced to pass by a large wagon wheel on a cart used to transport the armies Yurts. All those whose heads were higher than the linchpin that held the wheel on the axle were also beheaded. It is said that this removed most of the elders, men and women thus disposing of any potential revolt leaders. The remaining people were sold into slavery, raising vast amount of money for the Mongol empire.

The infamous piling of a “pyramid of severed heads” happened at Nishapur, where Genghis Khan’s son-in-law Toquchar was killed by an arrow shot from the city walls after the residents revolted. The Khan then allowed his widowed daughter, who was pregnant at the time, to decide the fate of the city, and she decreed that the entire population be killed. She also ordered that every dog, cat and any other animals in the city be slaughtered, “so that no living thing would survive the murder of her husband”. The sentence was duly carried out by the Khan’s youngest son Tolui. According to widely circulated stories, the severed heads were then set in separate piles for the men, women and children.

Lest we think the Khagan was simply a destroyer, he also developed the first empire wide postal service known, secured the route of the “Silk Road,” which became the route connecting east and west, building the connection that began sharing vast amount of knowledge throughout the known world.

And the Man Bun? Chinggis had sent a group of Mongol Officials to treat with the Shah of the ancient city of Otar. Angered by the demands of the Mongols, he had the entire delegations heads shaved, a mortal insult in the Mongolian culture. The men were beheaded and their shaved heads returned to Chinggis. Outraged the Khagan quickly attacked and took the city executing everyone in it and having molten silver poured into the ears of the ministers of Otar for refusing to listen. The city was then razed. Today it is a windswept ghost town in Khazakstan and has been for nine hundred years.

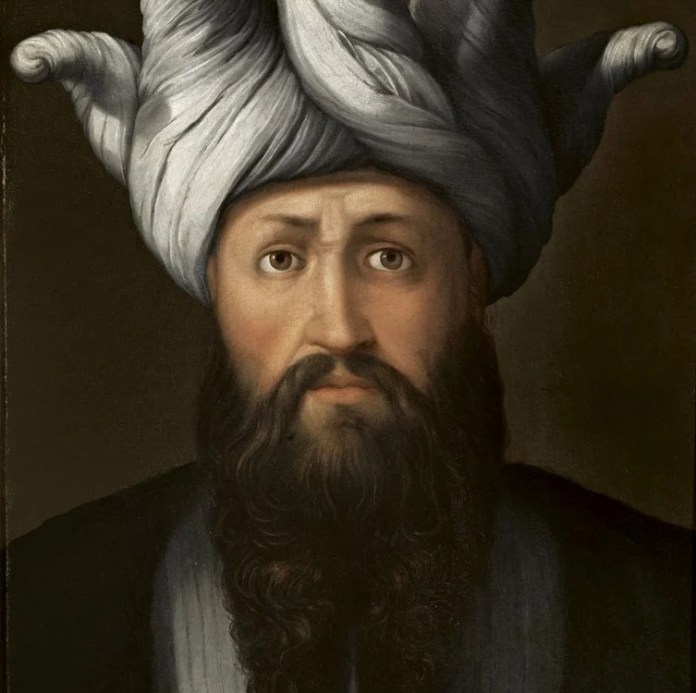

SALAH AD-DIN YUSSUF IBN AYYUB: BORN: 1137 AD-DIED: 1193 AD

Known as Saladin in the western world, Salah Al-Din was born a Kurd and was of the Sunni Muslim faith. At the height of his power he ruled Egypt, Syria, the Hejaz, (western Arabia), Yemen, Iraq, upper Africa and Nubia.

Each day he would arise from his bed, bathe and his wife Ismat Al Din Khatun would brush his hair, rub it with scented oils and roll and tie it into a topknot, known as a Tuft. Under Islamic law of the time, a man may wear hair past his shoulders or shave his head. Salah Al Din wore his Tuft under his turban.

He is most famous in the western world as the man who ended the European ruled state of Outremer formed after the 2nd crusade. The third invasion of the middle east, the 3rd crusade, he defeated Richard the I, Philip the II of France and Fredrick I of Germany’s combined armies. None ever never saw Jerusalem but did in the end establish a truce guaranteeing safe travel to holy sights if Europeans traveled unarmed. The coast from Tyre to Jaffa was left to Christian control. For the Europeans the primary outcome was the theft of books which the Muslim civilizations had saved after the fall of Greece and Rome which when transported back to their respective countries and translated, laid the foundation for advanced learning and the beginning of the Renaissance.

Salah Al Din was a generous man. He bought Christians out of slavery, established dozens of schools and libraries and when he died of fever in 1293, he had only one gold coin and forty of silver, not enough to pay for his own funeral. He had given it all away. He is buried in Damascus, Syria.

TAKEZAKI SUENAGA: BORN:1246 AD-DIED:1314 AD

Suenga was a Samurai. During the Mongol invasion of 1274, Suenaga fought at Hakata under Muto Kagesuke. Suenaga went to great lengths to achieve what he viewed as the honor of the warrior. Although under orders from Kagesuke to pull back at the beginning of the engagement, Suenaga disobeyed, saying “Waiting for the general will cause us to be late to battle. Of all the warriors of the clan, I, Suenaga will be the first to fight.”

The Mongol’s attempted invasion of Japan came after Kublai, who was Chinggis grandson and heir, showed his irritation with the Japanese refusal to pay tribute to the Mongol Chinese. In a letter to the Shogunate of Japan he stated….But now, under our sage emperor, all under the light of the sun and the moon are his subjects. You, stupid little barbarians. Do you dare to defy us by not submitting?

— Letter from Kublai Khan’s ministers to Japan, 1267

This kicked off what I like to call the war of the buns. After two failures, the second primarily because the Chinese battle fleet was ravaged by a typhoon which would forever after be called by the Japanese, Kamikaze, which translates roughly to divine or spirit winds. Chinese, Mongol, and Korean invaders who weren’t drowned were killed by the Samurai, their heads with the characteristic Man Bun scattered on the western Japanese coast by the tens of thousands.

Suenaga’s scrolls tell a much different story. The Japanese Samurai needed no help in defeating the Mongols. They were equally adept at savage warfare and after two tries the Chinese gave up. The “Divine Wind” is just a good story.

The Venetian merchant Marco Polo was present in China during this period was a first hand witness to the Mongol wars as he traveled through China and southeast Asia.

The frivolous term “Man Bun” is called the Chonmage in Japan. The sides of Suenaga’s head would have been shaved and the remaining hair tied at the top to assist in keeping his helmet in place.

Suenaga has left a record of his deeds during the wars on a scroll he commissioned in 1293. The scrolls are kept in the collection of the Museum of Imperial Collections in Tokyo, Japan.

KANGI YATAPI/KA GE TOU CHA: B: MONTH OF THE CRACKING TREES-DIED 1884 AD

Best known to historians as Crow King, he was a member of the Hunkpapa band of Sioux. One of the primary war chiefs, he led 80 Sioux warriors up Calhoun hill, allowing Crazy Horse and Gall to surround the remnants of the 7th cavalry and send the foolish Colonel into the pages of history.

Crow King rose from his blankets early on that morning in the moon of the Red Blooming Lilies. Stepping outside his tepee he sniffed the air of dawning, smelling the dry grass and the scent of dried horse dung coming from the vast herd of ponies beginning to graze on the plain west of the Greasy Grass. Rolling and stretching his shoulders he looked forward to a good day. Walking east to the slow running stream he drank his fill, washed his teeth and returned to the tepee where his wife Ptesan Luta Win and his two daughters, Hintukasan who was five and Tingle Ska Luta, one year old were. Crow King relaxed on his seat after breakfast and asked for his pipe. Suddenly a young boy, stumbled into the tent, out of breath stammering that the pony soldiers were coming down the river.

Crow king stepped outside and up the river he could see the bluecoat horsemen coming at a dead run. He quickly grabbed the boy by the arm and told him to go to the pony herd and fetch his horse. As he stepped back into the tepee he looked over his shoulder and noticed the cavalry had pulled up and formed a skirmish line. He didn’t understand this because his end of the village was completely unprepared for battle. He turned back and entered the tepee asking his wife to bring his weapons while he attended to his warpaint. Quickly twisting his hair into the bun called by Indians the scalp lock, he took the wrappings off the small pots of paint and began daubing his signature color across his chest and face. His forehead colored ochre and three vertical white stripes down each of his cheeks, he place three eagle feathers in his scalp lock and stepped back outside. The boy held his war pony by a grass rope tied around his lower jaw, barely holding on as the beast jumped and circled. The pony, knowing and responding to the excitement, while the boy spun, his feet off the ground at the end of the rope, Crow King threw his saddle and blankets over the beasts back and vaulted aboard, taking the the war bridle from the boy, the horse curvetting and circling, it took him a moment to gain control. Red White Buffalo Calf Woman handed up his rifle, tomahawk and shield, as he looked down to thank the boy a Short Hair soldiers bullet killed him, and his small body fell in the dust and lay like a little girls discarded rag doll. Someones son. Crow King said a silent prayer for the boys spirit. Controlling the pony with his knees he kicked it into motion and set off in a head long gallop toward the soldiers. Young men were bursting from between the teepees at a dead run, their ponies stretched out a full gallop, screaming their war cries determined to lay down their lives to protect the women and children. They knew what would happen if they failed. Hokahey

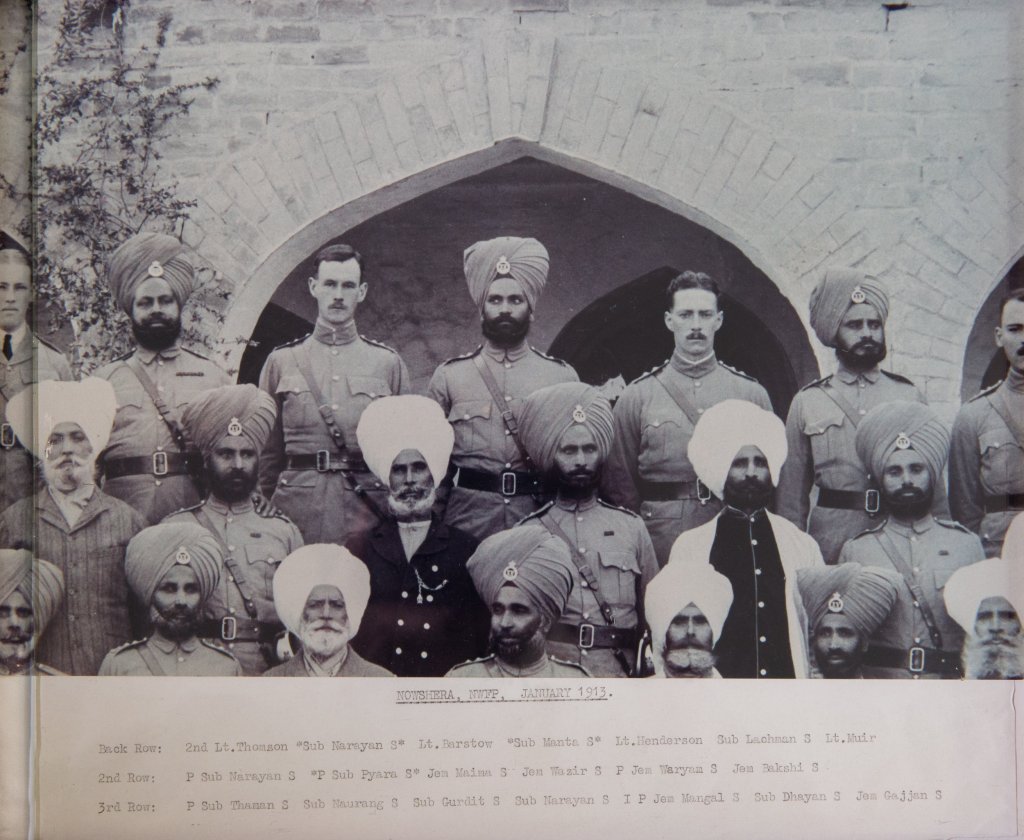

MANTA SINGH BORN 1890-DIED 15 MARCH, 1915

1.2 million Indians volunteered to fight for the British Indian Army in WWI, making them the largest volunteer army in the Great War. While Sikhs only make up 2% of India’s population, 22% of the British Indian Army were Sikhs. In World War I and II, 83,005 Sikhs were killed and 109,045 wounded fighting for the allied forces.

Manat Singh was one of those men. Manta Singh was born in 1870 into the family of Khem Singh of Salempur, Masandan, in District Jalandhar, Punjab. As soon as he left school, Manta Singh joined the 15th Ludhiana Sikhs in 1906. British officers prized Sikh soldiers, along with Nepalese Gurkhas, as coming from the so-called ‘martial races’. For Manta Singh and his comrades, the army was a good career option and one they took up willingly. As he was militarily educated , he rose up to the rank of Subedar (captain), above the ranks of most and just below that of the European officers in the army. Subedar was the highest rank that could be attained by a non-white in the British army at the time.

Sikism is the newest of the modern religions, the most recently founded major organized faith and stands at fifth-largest worldwide. Guru Nanak taught that living an “active, creative, and practical life” of “truthfulness, fidelity, self-control and purity” is above metaphysical truth, and that the ideal man “establishes union with God, knows His Will, and carries out that Will”.

Sikh’s are not allowed any hair removal – Hair cutting, trimming, removing, shaving, plucking, threading, dyeing, or any other alteration from any body part is strictly forbidden. Sikh men wear their long hair up and tied in a bun. This known as a Joora or Rishi knot. The turban is worn to protect the hair and as a symbol of Sikh pride. Manta and all of the Sikhs who served in the Great War never wore steel helmets.

At the start of the First World War, Manta Singh’s regiment became part of the 3rd (Lahore) Division sent to reinforce the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) fighting in France.

In a letter home, Harnam Singh described their welcome as the came ashore at Marseilles.

The people of Europe are very fair-skinned because in their previous lives they prayed and meditated so much. The cold atmospheres and climates of those countries mean that their skin color will never darken. They had never seen dark-skinned people before. They thought everyone in the world was white like them.

When we disembarked and mounted our horses, we headed off through the markets to our billets. Thousands of men, women and children were in the streets and on the roofs of the houses waving white handkerchiefs. They were saying something that we didn’t understand at the time. We later learnt that they were saying ‘bonju’ [bonjour], which is like our ‘sat sri akal’.

At the battle of Neuve Chapelle in 1915, 40,000 British troops, half of whom were Indians, Sikhs and Gurkhas assaulted the Germans on Aubers Ridge. The slaughterhouse which was the western front claimed 13,000 casualties in the two day battle. Four thousand of the dead and wounded were Sikh.

It was on this chaotic, deadly battlefield that Manta Singh saw his friend, British Leftenant George Harrison lying near death in a shell hole filled with water. Stumbling across an abandoned wheelbarrow he managed to drag and then lift Henderson into it and slowly wheel it back to the British trenches. Manta Singh was severely wounded while doing this selfless deed.

The result of the battle was recorded in the regimental diary as…

The ground in front of the British lines were Indian and German corpses and the whole place showed signs of heavy fighting that had been going on there.

The stretcher bearers were at work all night picking up the wounded. We had Subedar Gattajan killed and Subedar Manta Singh wounded.

About 60 other ranks were killed and wounded.

Regimental War Diary, 15th Ludhiana Sikhs

Manta Singh was evacuated to England because the front line hospitals were overflowing with the wounded.

A certificate signed by the Chief Resident Officer at the Kitchener Indian Hospital in Brighton lists Manta Singh’s wounds as ‘one, gunshot wound, left leg, two, gangrene of leg and toxemia.’ Manta Singh had one leg amputated, but unfortunately succumbed to his injuries and died a few weeks later on 15 March 1915. There were no antibiotics in 1915 and gangrene was almost always fatal.

His body was taken to the South Downs and cremated in the open air and his ashes were scattered in the sea.

Manta Singh’s friend George Henderson survived the war and ensured that Manta Singh’s son, Assa Singh (1909-2003), was taken care of and he encouraged him to join the Sikh Regiment like his father before him. Assa Singh developed a friendship with Captain Henderson’s son, Robert Henderson, and both actually served together in the Second World War.

Assa Singh fought in the Eight Army against the Nazis in North Africa, then in Italy. After the war he became a Lieutenant Colonel before retiring from the Indian Army in 1957.

The Sikh roars like a lion on the field of battle,

And yields up his life as a sacrifice:

Whoever is fortunate enough to be born a Rajput

Never fears the foe in battle:

He gives up all thought of worldly pleasure,

And dreams only of the battle field:

He who dies on the field of battle,

His name never dies, but lives in history:

He who fronts the foe boldly in battle,

Has God for his protection:

Once a Sikh takes the sword in Hand,

He has only one aim: victory!

These are the men, who, down the centuries wore the “Man Bun.” If a person is to make a joke about a mans hair, know of what you speak.

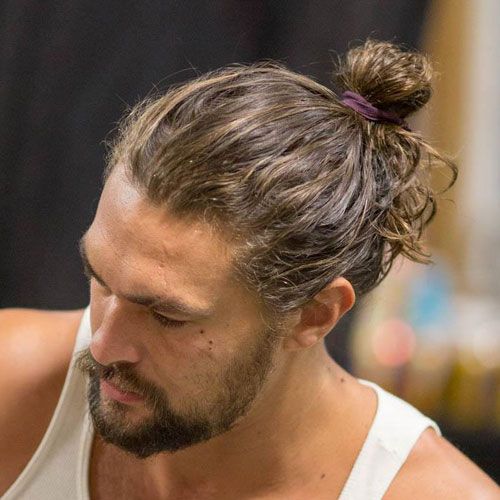

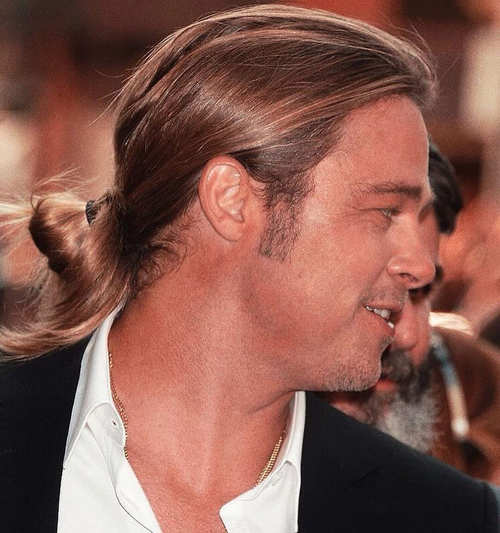

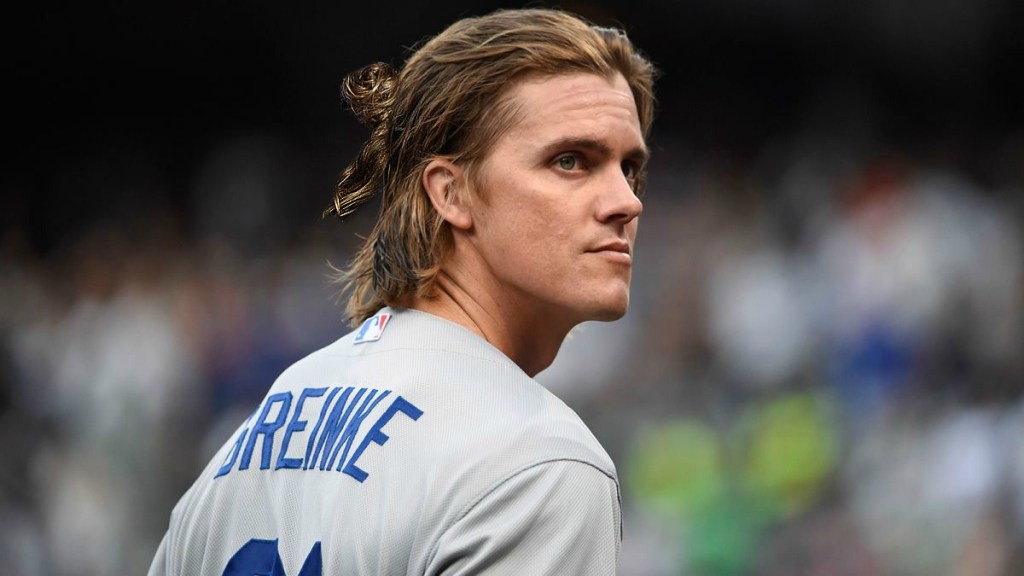

I want to thank my cousin K J and her best friend Judy for the subject idea and just for fun I added the photos below of modern men who wear it.