The Calf Shed

Michael Shannon.

We had a small red shed on the ranch. It was the greatest place explore when I was a kid. It had cobwebs that had been spun a century earlier. There wer enough Black Widows to populate half San Luis County. My uncle Jackie said once that some of the spiders knew Captain Guillermo Dana who owned the old Nipomo Rancho. He was always saying stuff like that and you could never tell if it was true or just funny a uncle’s bushwa.

It had two doors, one at each end. They were Dutch doors which was a true novelty as I had never seen or heard of one before. The only Dutch I knew was the woman on the Old Dutch Cleaner can who looked vaguely sinister with her purposeful stride and big stick, obviously out to punish the unclean. I can’t recall ever seeing the top half closed except during swallow season. In true country style no one wasted any time doing useless things so each door was closed and opened perhaps once a year.

The small building served four purposes. The left side was divided into small stalls which were occasionally used to house calves that needed hand feeding or just a little extra care for a bit. For kids having a small red and white Hereford calf that you cold bottle feed, well there’s not many things that can top that. The little heifer being quite naturally friendly who would cuddle up to you or suck milk from your fingers is hard to beat. Usually one stall would be full of feed sacks, special meal, seed and always a few blocks of salt lick. Red, white and pink depending on their us. Did we lick them, you know the answer. Seeing that saving was considered a virtue, there was one stall with heaps of used and empty gunny sacks just in case. There were cotton feed sacks too, piled in a corner some, no doubt as old as the feed and grain business my grandfather, Al Spooner and David Donovan once owned.*

The sacks were home to the Kitties. Kitties is really the wrong thing to say. They were fierce predators an not interested in little boys. Their job was to keep the shed clear of mice. There are few things more attractive to a mouse than a shed packed with grain to eat. They were shy cats and not always visible, hunting was their job and during hunting hours were occupied wherever they could find a victim. No names for them, for decades the cats went by Cat, all of them. They never ate from a can or bag of cat food. They had to pull their own weight. Domesticated animals like dogs and cats were mostly for utility and not human companionship.

The little place was fragrant beyond belief and it changed it’s perfume like an elegant woman dressing for a dinner. The rich heady smell of grain, the pungent manure from the little calves and in the cold of winter it exuded a musty smell of old redwood lumber and always the rich, sweet sweet smell of Hay. Depending on the time of year wisps of dust motes drifted in the light from the doorway’s like a veil on a beautiful Spanish maiden painted by Velasquez.

The best thing though was the little corner where the tools were kept. All those drawers filled with haphazard piles of metal we assumed to be tools of one sort or another. Most carried a patina of rust, some just dusted with and some stuck together by lumps of it, glued together for no one knew how long. Wrenches of indeterminant use perhaps from some long gone piece of farm machinery, like tractors and old milk trucks, some predating the electrical motors used in the milking barn. Ball peen hammers, an old fashioned straight clawed hammer at least a century old and in the bins rusted clumps of fence staples, nails, some porcelain insulators left over from putting in the electric fence and bolts with square heads that hadn’t seen a use for 75 years.

Unique to me, a child born after the big war, many of the tools were curvilinear, embossed with the names of the manufacturer, some with molded decoration that wasn’t just for utility but for beauty. Designed by the last generation that saw pride in the craftsmanship involved in the pure design of a useful object.

The 1950’s spelled the end of the “fix it” age. Men who were our fathers had grown up in the Great Depression and as adults went to war, the most destructive war in history. Historians have said that the US defeated the Germans, not with superior tactics but with the fact that American boys could fix a tank and the Germans couldn’t. Baked into them was a certain self sufficient attitude that they could take care of themselves. They didn’t need help and like my father would rather die than ask for it. If something broke they fixed it. If something was needed they made it. They didn’t go to trade school they learned from others or simply invented what they needed. They didn’t need much, things could be repurposed. Nothing was thrown away, we had a gully with trucks, cars, tractors and farm machinery rusting in the sun where a part might be salvaged and put to a better use. If my uncle Jackie needed a stock trailer, he hauled a rear axle from the ditch, got out his tanks and welded up a frame. He dragged some used lumber from the scrap pile of odds and ends some of it dating back to some time before my great-grandfather’s day, got a handful of nails from the rusty nail bin and when he was done mixed a few shades of green paint together, brushed it on and he had a perfectly useful trailer. Rolling down the 101 on the wheels from an old Buick and a taillight taken from a Model T, With mismatched hub caps one reading Buick and one Chevrolet, It served him well for fifty years. It’s not used anymore, it sits in the old hay barn, it’s tires flat and the green paint faded but if you needed it a little air in the tires and it would be good to go.

It was all wonderfully “Make Do.”

One of the first “Essential” stores in our little town was the first hardware store. If you are a regular at one of the modern hardware stores today you might be surprised by what those old places stocked. Those old places officially died in Arroyo Grande on February 21st, 1958. The Chief wasn’t quite sure what happened but the old building built in the 1889 was a total loss. A nearly 75 year old building where the amount of Case oil. Kerosene, Lamp oil and desiccated cardboard boxes holding assorted glass fuses or leather drive belts, frayed at the edges and emitting a small cloud of dust whenever touched was simply waiting to immolate itself.

For those of us old enough to remember the dark, dusty stacks of shelve and boxes, greasy, oily wooden floors fronted by the long counter at the front, the varnish long turned to caked, flaked shreds of black chips resembling the dried mudflats of the lower valley where the adobe mud is completely tessellated in the dry late summer. The green enameled light shades hanging from the ceiling had a thick coat oily dust as they hung on the twisted copper “Rag Wire” so treasured by the rats who lived in the attics of old buildings. The tasty oil impregnated linen which passed for insulation just begged a rat to nibble on it exposing the wires which would short circuit and catch fire at a moments notice.

The fire, however she started left nothing but a heap of ashes, charcoal and twisted metal, It also ended the era of a type of store that doesn’t exist anymore except in small, isolated communities across the country.

Don Madsen was the last owner of the business which was started By Charles Kinney in ’85, thats 1885 by the way until it was passed on the Carmi Mosher in 1909. Carmi sold it to Harold Howard in 1919. Harold, a local boy having grown up with my grandfather kept the business going as Howard & McCabe until 1950 when he retired and sold it to Don whose son I went to school with. Small towns you know.

Don had worked in the hardware business since he was a high school student had returned from WWII where he served as an MP on occupation duty in Germany. He went right back to what he knew.

Occasionally my dad or uncle would need something in the way of bolts and nuts or hand tools that they couldn’t find in the tool maze of the calf shed and would be forced to actually buy something. Stores were the place for what you didn’t have. Take the broken piece to Don and lay it on the counter. He would pick it up, heft it to determine its weight then give it a serious look and say, “Yeah, we might have something like that. Let me go see.” He would disappear into the stacks of goods between the ceiling height wooden shelves and bins and begin his voyage of discovery. Assorted bangs and bumps would come from the back and finally he would return and lay a new one or close proximity on the counter. He didn’t have to say Eureka but there would be some head nodding and low noises as both customer and seller acknowledged that it was in fact “Just what I need.”

Dad would pull out his billfold, a term I have’t heard in decades and say, “How Much?”

“Six bits will do it George.”

Dad would put the billfold back in his right hand jeans pocket and then fish around in the one in front until had a small handfull of stuff, an old slotted screw with the slot turned out useless, but you never know, maybe hang on to it awhile just in case. In amongst the seeds, a piece of wrinkled Juicy Fruit gum and foxtails were some nickels, dimes and a few quarters, just enough.

Dad would ask about Clara and the boys and Don would return the favor.

Whatever that piece of hardware, it would someday, when it’s immediate usefulness was done, end up in the calf shed where it likely still resides.

After all that old hardware store was not a too distant kin to the calf sheds.

When she burned in ’58 it marked, in a real way the end of frugality nurtured by “Make Do” and the way we live now where everything has a date on which it will magically die.

Epilogue.

The though that planted the seed for this story was a trip to the local hardware store the other day. Big, bright and shiny, all the trim painted fire engine red and the first thing you see when the automatic doors open is a large open space with military straight rows of Barbecues. Stainless steel, black enamel, wood burning, pellet burning or gas or electric. Line up like they just graduated from boot camp they are surrounded by all the accouterments designed to make you a perfect cook. Tens of thousands of dollars worth.

There is a paint department where you can buy hundreds of different colors. Anything to suit your fancy. They have more cleaning supplies, mops, and brooms than you can conceive or could find at the grocery store. Every one is persistently helpful but no one knows much of anything about anything. But they wear a red vest to show that they might. Very official.

Unlike Don, they will look at your problem, scoff, and advise you to buy a new one, or a box of fifty when you need just the one. And believe me, the inferior new one that will never deserve a place in the calf shed.

Dad Shannon at the BBQ pit. Family Photo

For a kid that grew up with BBQ cooked over a pit which was just a handy hole behind the house and a grill made of heavy rods left over from some job they did and whose grandparents painted their dairy barn and silo pink because there wasn’t enough of either color available during WWII so they just mixed them up and it was good enough and a great lesson too.

“Make Do.” That was it.

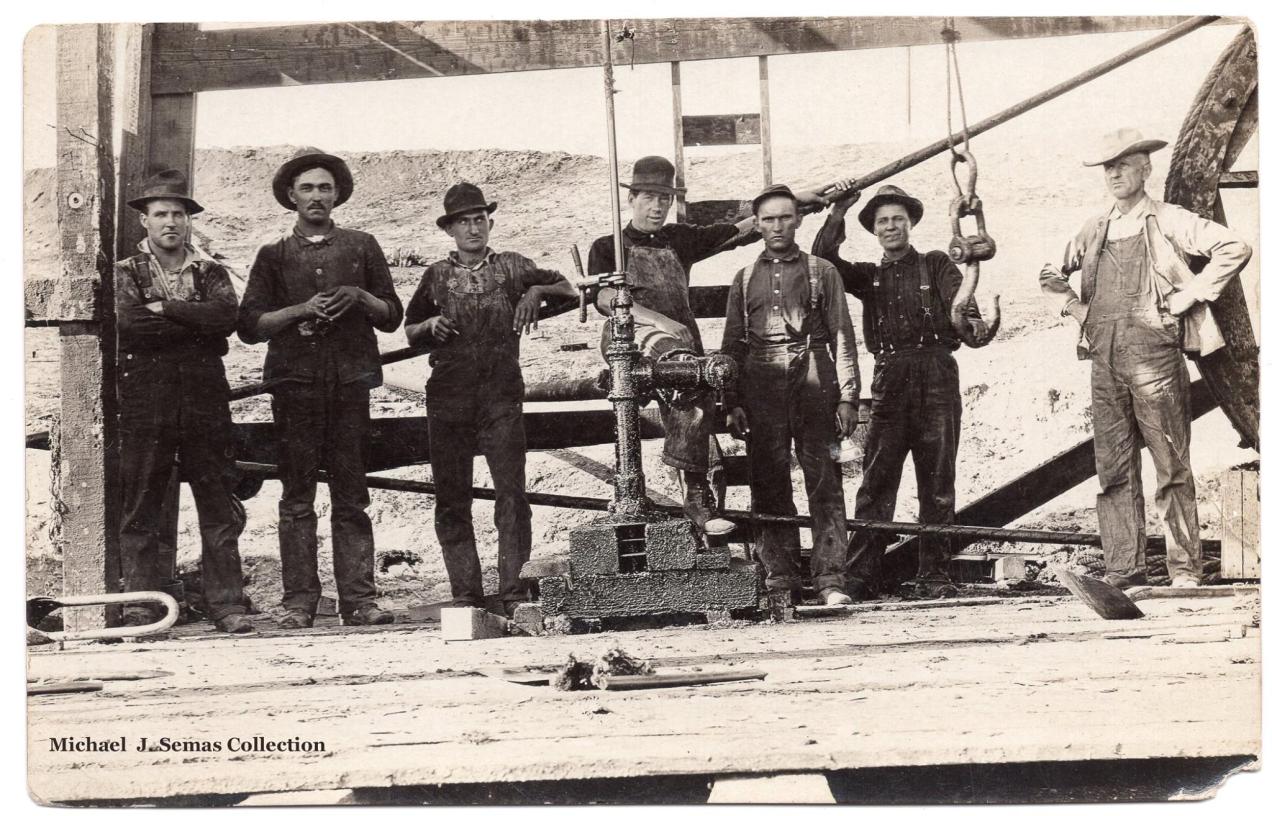

Cover Photo: The old hardware store on the right in 1906.

Note: The Madsen’s moved their store across the street to the old Donati building and prospered for many years but it was never the same.

Michael Shannon has been known to keep random pieces of lumber for fifty years, you know, just in case.

Please Subscribe.

The Twelve Hour Tour

Chapter 14

Michael Shannon

Bruce listened intently. With his left hand braced against the wall, head down and the receiver jammed aginst his right ear. He softly repeated, “Yes sir” several times. After a few minutes he said “Thank you Sam, I’ll be there as soon as I can.”

He hung up the phone, turned, took off his hat and held it as he put his hands on his hips and arched his back as he exhaled.

He looked at Eileen then Marion and said “That was Sam Mosher, I’m going back to work. I have to be in Long Beach as soon as I can. I’ll leave tonight I gotta go gas up the Ford. Eileen can you pack me a bag and something to eat?”

Bruce rattled down the Cahuenga pass into Los Angeles. He’d been on the road for a day and a half, slept in the back of the Ford last night and woke this morning sliding into the drivers set, setting the Magneto and advancing the spark, he kicked the starter button and turned her over. He figured with a quick stop for breakfast he’d roll down Alameda Street and into Long Beach just after sunup.

Rolling through Huntington Park then South Gate he drove into the fields and scattered houses of Compton and he could smell it. Drifting east on the morning breeze, the unmistakeable heady mixture of crude oil perfume. A strong, pungent, and a little bit sweet, the odor can be reminiscent of a mix of gasoline and tar, with a distinct earthy or petroleum scent. Some people find the smell unpleasant, but to an oilman It smelled like home.

Exhausted by the drive the odor washed over Bruce and caused his energy to start flowing. With his hopes soaring he drove down Alameda until he entered Long Beach. The City of Long Beach had a population pushing 150,000 and had doubled since the census of 1920. Once it was primarily a Beach resort for the retired and wealthy but the discovery of Alameda no.1 up on Signal Hill had changed the city drastically. Midwesterners flocked to the Hill to get rich. Leasemen, Drillers, Salesman, factories that built steam boilers and rolled pipe quickly surrounded Long Beach. Houses went up as fast as they could be built. The Navy was moving part of the fleet to the new Navy Yard on Terminal Island. During the booming twenties Long Beach became the home of sailors, oil field workers, workers in auto assembly plants, soap makers, a vast fishing fleet made up of Japanese immigrants and people coming to the edge of America looking for the main chance.

Signal Hill with The San Gabriel Mountains to the north. 1931 Calisphere photo.

Long Beach city was part of the Mexican land grant Ranchos Los Cerritos, the Little Hills and Rancho Los Alamitos. the Little Cottonwoods. It had been for two centuries dedicated to cattle raising. The small villages of the area were distinctly rural and grew slowly over time. Wildcat drillers began poking around in the 1890’s and when Edward Doheny brought in the first well in 1the Los Angeles field* in 1892 it was “Katie, bar the door.” The Los Angeles Oil Field made Edward Doheny one of the richest men on earth. “Richer than Rockefeller” as the song “Sunny Side of the Street” says from the old Fats Waller tune and it was true. Richer than Rockefeller.

Beginning in the late 15th century, Spanish explorers arrived in the New World and worked their way to the California coast by 1542. The colonization process included “civilizing” the native populations in California by establishing various missions. Soon afterward, a tiny pueblo called El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles de Porciúncula would be founded and prosper with the aid of subjects from New Spain and Native American slave labor.

One Mestizo Spanish soldier, José Manuel Nieto, was granted a large plot of land by the Spanish King Carlos III, which he named Rancho Los Nietos. (The Grandchildren) It covered 300,000 acres of what are today the cities of Cerritos, Long Beach, Lakewood, Downey, Norwalk, Santa Fe Springs, part of Whittier, Huntington Beach, Buena Park and Garden Grove. It was the largest Spanish or Mexican land grant issued being nearly ten times the size if Catalina Island.

Soon prospectors started putting down hole everywhere. They found Oil in Santa Fe Springs and in a couple of decades were pumping in Beverly Hills, Torrance, Southgate Dominguez Hills and Seal Beach.

But Alamitos #1 was the biggie. She came in with a roar heard in downtown 24 miles away. Drilled on the at the northeast corner of Temple Avenue and Hill Street in Signal Hill. Spudded in on March 23, 1921, it flowed 590 barrels of oil a day when it was completed June 25, 1921, at a depth of 3,114 feet. The discovery well led to the development of one of the most productive oil fields in the world and helped to establish California as a major oil producing state.

Alamitos no. 1. Discovery Well, June 25th 1921. Signal Hill, Long Beach

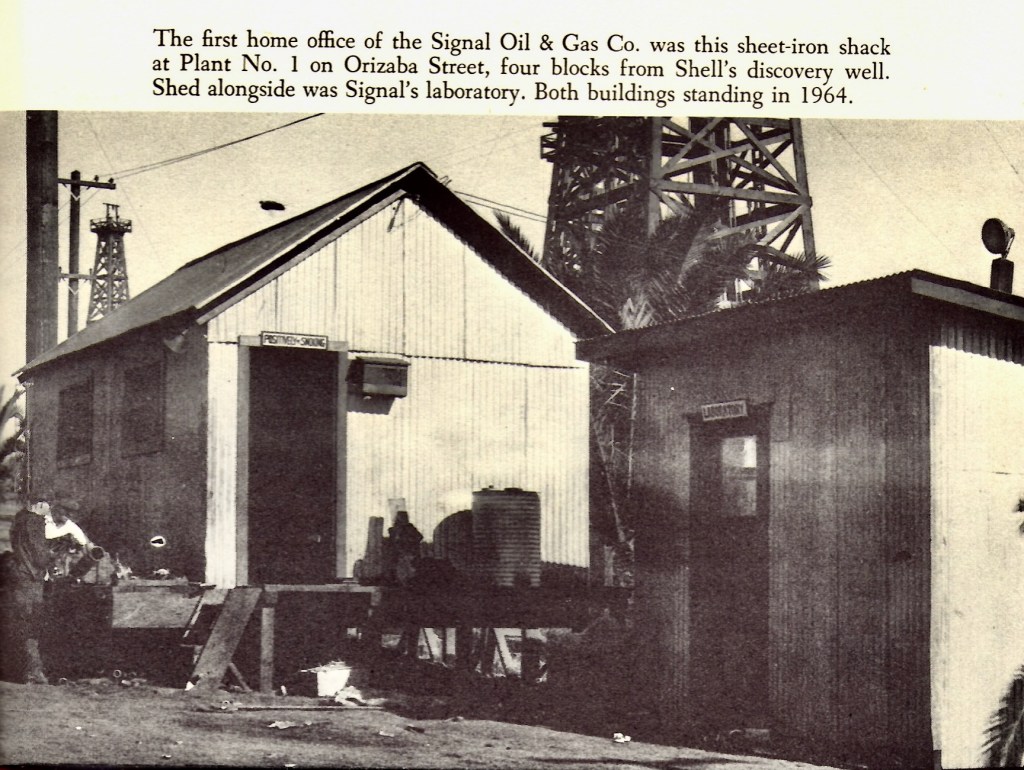

Ten years later Bruce made the turn from Alameda onto Willow, passing the Sunnyyside* Cemetery and headed east towards the Signal Oil and Gas headquarters building. Building isn’t exactly the right word though. Years later Signal would move into a modern building on Beach Boulevard and later still build its’ own headquarters building on Wilshire and 7th in downtown Los Angeles. This headquarters was was no more than a tin shack in the middle of the field itself. It may be a slight exaggeration to call it that but Signal was just eight years old and had begun life as a refiner of natural gas and owned no wells of its own in the beginning.

In the run up to the great depression Sam Mosher’s nascent company was struggling mightily to raise money to stay in business. Consequently they were using bond sales, private money, partnering with large oil companies like Standard Oil of California and banks trying to stay afloat. Independent companies were failing on nearly a daily basis as the price of oil tumbled. The big companies were cancelling contracts to the independents in order to protect their own. Breaking bonafide contracts was illegal but they had the money and lawyers so the attitude was independents be damned. Crocker Bank pulled its loans and a loan agreement with Giannini’s Bank of America kept them afloat.

The company under Mosher’s leadership invested in oil leases in Texas, the Westside of the San Joaquin, Summerland and a few abandoned leases in Elwood near Goleta. The idea was to diversify their holdings into drilling in order to provide product for their little refinery.

As the Ford toiled up Signal Hill the couldn’t help but wonder what the job would be. It didn’t matter that much, whatever it was he needed it.

Bruce and the Ford were both tired, it had been and long lonely drive He wanted to show Mosher that he had extraordinary drive hence the immediate drive down to Long Beach. It was very important to demonstrate that he was always ready to go. He had met the man a few times but had mainly dealt with his drillers and superintendents when he was working the Goleta and Summerland fields.

He pulled into the yard which was filled with trucks, automobiles parked any whichaway. Climbing down from the car he stretched than walked quickly toward the headquarters building. He could see, hear and see welders pipefitters, draymen, ditch diggers, bricklayers concrete masons, electricians, carpenters and plumbers at work everywhere. They were coming and going, these skilled laborers moving between rigs, some working for just one company but most were day laborers or were moonlighting, paid cash money they represented the itinerant workers seen all over any oil fields. Bruce stepped over some drill pipe and paused turning to take in the hustle and bustle and chatter of the men around. The sound of boiler valves popping off extra pressure, steam whistles, the chug chug of diesel engines pulling the linked chains that spun the drill string, sucker rods in an endless rise and fall lifting the crude from near a mile underground. When the wind blew the massive wooden derricks bent to it, creaking and groaning with a dismal sound. An ordinary man would be cautious and afraid his ears ringing, eyes stung by the constant blend of exhausts, the sewer gas coming from the drill pipes with its semi-putrid odor all of it wafting about lighting on and tainting every surface. Grandpa once said you didn’t need any hair oil in the patch, it was provided for free. Always buy a black car and never wear a white shirt.

Headed for the steps he hopped over every kind of detritus, crushed cans, butts, random paper blowing about, there were gobs of crude oil everywhere and the wooden surfaces of the buildings and derricks were soaked with it. It was no place for a fastidious man. A very careful man but not one overly finicky.

Bruce climbed the steps stepped to the door and knocked on the door trim, there was no door, someone found a better use for it he guessed.

Inside at an old desk scarred by hard use, its edges burned by cigarette butts left too long, sat a man. Dressed in stained Khakis and hard used work boots. He wore a green long sleeved work shirt, cuffs buttoned against the dirt and grime, no man exposed any more of his body than was necessary on the job. Pants held up by braces, no man working in 1931 wore belts, too restrictive. He rose from behind the desk sliding back the bent wood chair that served as a seat with a rasping screech, he reached up with his right hand and pushed back his typically stained and dirty Fedora. The smile above his jowls flashed as he held out his hand and said “Hello Bruce, damned good to see you.” Grandpa smiled back and took the hand, “Good to see you too Bob.”

It was Robert M. Pyles, Signals drilling superintendant for Huntington Beach. He said, “Sit down Bruce.” Bruce pulled up the only other chair and sat. Bob pushed up his black heavy rimmed glasses, used his forearm to sweep the piles of paper on the desk to the side, reached down opened a drawer and pulled out a binder and laid it on the desk. “These are our reports for Elwood, I want you to take a look at them and tell me what you think.” Bruce slipped his reading glasses out of their case, put them on and slid his chair closer to the desk.

He pulled a crushed pack of Chesterfields from his left front pocket and offered one to Bob who declined. Picking a match from a box on the desk he scratched it with his thumb held it to the smoke. Fired up he leaned back blew the match out and closed his eyes for a moment to let the smoke from the phosphorus match head clear and then bent to the binder and began to read.

After an hour or so and some discussion the two men sat back in their chairs. Bob pulled open a desk drawer and snagged a fifth he kept there, blew the dust from two coffee cups and poured a couple fingers in each one. He took one and slid the other one to Bruce and said “So you’ll take the job?” Bruce grinned, nodded. They reached out and clinked the cups and threw it back. They stood up reached across the desk and shook again. Bob said, “You’d better call Eileen and tell her to pack up and get down to Santa Barbara.”

That is how the employment contract was signed. The old way.

Cover Photo: Willow Street and Sunnyside Cemetery in Long Beach 1930. Long Beach History photo

*The Los Angeles field is is still pumping. It runs from the east near Dodger Stadium into downtown at Alvarado Street.

**The Sunnyside Cemetery would not lease its ground for oil drilling for obvious reasons. It was completely surrounded by forests of wells. More on that later.

Michael Shannon is the spawn of drillers and ranchers. He write so his children know who they are.

Twelve Hour Tour

Come the Little Giant.

Michael Shannon

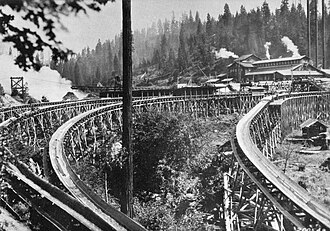

Madera, California. Madera was founded in 1876 as a lumber town at the terminus of a flume built by the California Lumber Company. The town’s name, meaning “wood” in Spanish, reflected the timber industry that spurred its growth. But if you were looking for a job in the mills you could forget that. The Depression ultimately brought an end to the lumber era. A collapsing market for wood forced the Madera Sugar Pine Company to cut its last log in 1931, and the mountain sawmill closed shortly thereafter. The marvelous 63 mill long flume from the mountain mill to the planing mill in Madera went dry. By 1933, the company’s assets were liquidated, marking the end of nearly six decades of logging that had been the foundation of Madera’s economy.

When the timber industry died, agriculture emerged as Madera’s primary business. Farming had already begun in the late 19th century, with irrigation from the San Joaquin River boosting crop production. The 1930s marked a significant shift from sawmills to farms. Unemployed lumbermen and mill workers left for more likely places and were replaced by migrant farmworkers, including many Dust Bowl refugees, who found seasonal work the fields and orchards which now dominated the economy.

The big cattle ranches who grew their own feed were being squeezed out by the terrible drop in meat prices and consumption. There was so little cowboying to be done that they got off their horses and began working the stockyards and packing plants. Most of th the big ranchers failed and the land was sold or just abandoned for unpaid taxes.

Henry Miller a former San Francisco butcher began buying land in the central valley. Miller built up a thriving butcher business in San Francisco, later going into partnership with Charles Lux, a former competitor, in 1858. The Miller and Lux company expanded rapidly, shifting emphasis from meat products to cattle raising, and soon became the largest producer of cattle in California and one of the largest landowners in the United States, owning 1,400,000 acres directly and controlling nearly 22,000 square miles of cattle and farm land in California, Nevada, and Oregon. Madera was smack dab in the middle of the Miller and Lux holdings and Henry Miller was ruthless in controlling not only the land he owned by any adjacent properties. He also used bribery especially keeping tax assessors and town officials in line. Miller and Lux also became owners of the lakebed of the Buena Vista Lake. Miller played a major role in the development of much of the San Joaquin Valley during the late 19th century and early 20th century. His role in maintaining and managing his corporate farming empire illustrates the growing trend of industrial barons during the Gilded Age.

Bruce and Marion were aware of the terrors associated with industrial operations in the oil fields. Keep wages as low as possible provide nothing but temporary and work keep the unions a bay. Company loyalty only went one way, up. After more than ten years in the wells Bruce had thought that he would be protected by his superiors but with Barnsdall closing down it’s wells in Santa Barbara and literally sneaking out of town and back to Texas both men were left adrift. By the middle of 1930 there were a dozen or more men for every job. Having to retreat to Madera took them far away from the areas that were still operating.

Looking for work by telephone was frustrating. How many times did he spin the crank on the old wall phone and try to contact some one from the rumpled list of operators, contractors and owners taped to the wall in the farm house kitchen with pieces of yellowing Scotch Tape.

“Bruce, we might have something coming up in a couple months if the big boss can rustle up some financing so we can afford to drill, but I don’t know. Wyncha give me your number and I’ll call ya if sumpin breaks.”

They tried driving down the 130 miles to Bakersfield and the westside around Taft but that turned out be just a waste of gasoline.

So it was back to farming. They worked the ranch for grandpa Sam Hall and hired out for the various harvest seasons. Spending days climbing ladders to pick Apricots, working the Walnut orchards and the nut processing plants. There was a vast amount of cotton to hand pick too. They got by.

People had to eat no matter how poor they might be so agriculture stumbled ahead. My dad said that during the depressions farmers didn’t starve in California. My family in Arroyo Grande had a dairy, kept pigs, chickens and a goat. They grew their own feed and he said the old fashioned barter system kept them in vegetables which people traded for milk. They traded beef with the butcher Paul Wilkinson instead of cash. Milk was good for bread at the bakery and my grandmother’s little bag of coin which she got from her milk deliveries was enough for the Commercial Market. He said it was rough but everybody got by unlike people in the cities and industrial areas. He said people got used to having less, they didn’t travel as much and simply entertained themselves with local theaters and the goings on at schools and picnics put on by the lodges and clubs. He siad the the community was closer and better of for it.

Bruce, Eileen and the kids muddled on. Madera was a good place to live. There was swimming in the river with their cousin Don Williams though for some odd reason neither my mother or my aunt Mariel ever learned to swim but there were boys there and they were just getting to that age. There are few things better than lazying about a slow moving California River on a frying hot and dusty day. Slathered in baby lotion and olive oil, Mariel and mom would lie in the cool water slipping down from the high Sierra and bake.

And bake it was. The San Joaquin valley is a hot place in the summer. In old farmhouses built out on the flat ground west of the foothills of the Sierra Nevada where the land acts like a mirror radiating the heat like a flatiron. Kids who ran barefoot had to sprint from shade three to shade tree to keep from burning their feet. The old Hall ranch house was a single wall place, no such thing as insulation unless you counted the folded newspapers stuffed in the spaces between the vertical sugar pine boards that held it up. AC was not even a dream yet. At night they would open the sash windows to hopefully cool the inside a bit and in the morning close all the blinds to try and keep the night’s cooler air from escaping. “Close the door” was the call, trying to get the kids to close the door as they went in and out on their endless imaginary errands. Mom said they hauled the mattresses outside onto the porch to sleep at night if they could. Their sheets were soaked in water when it was unbearably hot. In July and August temperatures at the metal Coca Cola thermometer nailed to the wall out on the covered porch hit over 100 degrees every single day. It was cooler at night, somewhere in the seventies but that wasn’t til long after dark.

Bruce, Marion and grandpa Sam Hall would sit out on the covered porch as the air cooled, smoking drinking and talking about the days affairs and the state of the country and oil in particular. Passing a pint around the talked about the terrible bog the industry was mired in and not only the oil business but the entire western world. They wouldn’t have known it then but it would go down in history as the worst economic depression ever recorded. Breadlines and soup kitchens were already forming in California, there was even one on Yosemite Avenue in downtown Madera. Unemployed men, many from the the professions or fresh out of college were forced to live in “Hoovervilles,” gatherings of shacks, tents and cars while they desperately looked for work of any kind. Migrant workers and their families began swarming into the Milk and honey mirage that was California to escape the dust bowl and failing cities of the east. Highway 99 was seeing a massive caravan of the hopeful and desperate heading north and south looking for work. It was nothing less than a tidal wave of the unfortunate flooding the state and willing to take any kind of employment.

Banks and business firms were closing their doors. Runs on banks by people desperate to withdraw what money they had caused bank runs all over the country. Nine thousand bank failed. With no reserves a bank could not lend money or earn money. Farmers were defaulting on the annual loans, business firm too. Many banks instituted foreclosures against oil businesses, the fear this caused in the highly speculative business sent companies running for cover.

The smaller independent oil companies were the hardest hit. Hundreds in California simply disappeared, walking away and leaving wells half drilled or simply capped. The majors just quit drilling altogether. The price of gasoline hit .09 cents a gallon in 1930, less than the cost to bring in and put a well online. It would get worse.

For Bruce and uncle Marion it was hard to see a way out. Bruce Hall was just thirty five years old with a wife and three children and what seemed the bleakest of prospects. The burden must have been nearly impossible to bear, but bear it he must.

The phone rang. It was two longs and a short, the Hall distinctive ring. Thats the way it was on the old party lines. Aunt Grace got up from the table where she was peeling peaches for pie, wiped her hands on her apron and lifted the receiver and put it to her ear, “Hello,” she said. “Yes this is the Hall residence, Bruce Hall? Yes he lives here, can I ask who’s calling?”

“My name is O. P. Yowell, Bruce knows me as “Happy, Is he around, they gave me this number to call at the office.”

“Why yes he is here, he’s down in the orchard. I can send someone to fetch him if you can wait a few minutes.”

“That would be fine Mrs. Hall, I’ll hold.”

Aunt Grace looked over her shoulder for the nearest available kid and spotting Barbara playing solitaire she said “Barb, can you run down to the orchard and tell your father he has a call. Tell him it’s a man named Happy.” She winked at her niece, “a man named Happy, how about that.”

She turned back to the phone and asked what the call was about then said “O K, I understand. It will be just a minute”

Barbara, she yelled as she heard the screen door slam, “Tell your father it’s a man called Happy from Signal Oil, he says that Sam Mosher wants to talk to you.”

“And hurry honey, It’s important.

Michael Shannon is surfer, teacher and World Citizen. He writes so his children will know where they came from.

Twelve Hour Tour

Chapter 13

Down In The Dumps

Michael Shannon

They pulled out of Goleta, the two 1927 model T’s loaded with whatever they could fit in around the kids the rest tied on the trunk platform at the rear. North from Goleta. The road, not by any means a highway yet wandered along the coast, a fine view of the Pacific Ocean until they entered the little valley at Gaviota where they would turn inland.

Entering Gaviota pass. Goleta Historical Society

The sharp little valley named by the Portola expedition for the unfortunate seagull it’s hungry soldiers killed and ate there in 1769 was little changed. The narrow break in the Santa Lucia mountains, the only one for a hundred miles in any direction was now wide enough for vehicles but just barely. Bruce and Eilleen were slowed by road work through the narrow pass because the old rusty steel bridge over Gaviota creek was being replaced by a modern one and contractors had begun laying asphalt north from Santa Barbara but once they were north of Refugio canyon where the hide droughers had once loaded Richard Henry Dana’s Bark Pilgrim with dried cow hide, there was only a graveled road for the next 45 miles.

They drove under the Indian Head rock at Gaviota which my mother didn’t like, she though it might fall down on their car, something she never got over. Then up the hill to Nojoqui pass and down to Buell’s, from there on it was going to be a dusty trip and they wouldn’t see another paved road until Santa Maria. They stopped at the tiny town on Rufus Buell’s Ranch where ate they lunch at the only cafe in town, Anton and Juliette Andersen’s Electric Cafe, featuring Juliette’s soon to be famous pea soup recipe.

The two cars burdened with most all they had, two couples and four kids passed by the Pacific Coast Rail road warehouse in Los Alamos where Bruce had once worked humping 90 pound sacks of grain from the ranches nearby and then they turned up the Los Alamos valley headed for Santa Maria. On the way they rolled through the old Graciosa townsite, Casmalia, and Orcutt where the men had their first jobs in the oil fields more than ten years before. The little company town where they had lived was still up on the hill above Orcutt but was falling into ruin as nearby towns with rented houses had sprung up where you could live in a little more comfort than the old Shebangs they had first lived in. There were still wells but many were shut down because oil was too cheap to pump. Oil Companies had not followed their own advice or any warnings about the financial crush that had already started in the early twenties. Casmalia oil companies were lucky to get 0.65 cents a barrel for crude at the wellhead. Compared to $3.07 in the early twenties this was a disaster for oil companies and Marion and Bruce and their families knew it well. It was the reason for this trip after all.

The price of oil meant gasoline was cheap, about .20 cents a gallon but money itself was losing it’s value. You could buy gasoline for pennies but you couldn’t afford to go anywhere either. The worst time was coming like a fast freight and the price of oil was going to fall even more as the depression deepened. No one can see into the future. My grandparents couldn’t have imagined what they and the country were in for.

They rolled through Santa Maria, crossed the Santa Maria river, dry at this time of year, and over the wooden bridge and the flats of the old Rancho Nipomo onto the mesa planted with, it seemed an endless forest of Eucalyptus trees marching in their perfect straight military rows all the way to the western horizon then down to the sea at Guadalupe beach. Finally cresting the edge of the mesa they rolled down Shannon Hill past the little house where the Shannon’s lived and where my father, future husband of Barbara Hall was finishing up his senior year of High School. They wouldn’t meet for another 13 years.*

Shannon’s 1928. Family Photo

It was a long long trip for the time but because the cars were loaded with what was left of their belongings Grandma and aunt Grace insisted they stay the night at Bruce’s father Sam Hall’s lot on Short street right in Arroyo Grande town. The motor court was just short distance away but money could be saved. There was no house on the lot yet but they said at least staying there no one would think they were “Tractored Out Okies.” In truth they were hardly better off but appearances were important. They had passed the pea pickers camps in Nipomo where Dorthea Lange’s photo of the migrant mother would be taken in a couple years and before they got to Madera they would see many squatters camps and desperate peopled camped on the roadside. You and your neighbor may be equally destitute but al least you have pretense and thats something people hold onto.

Today no one thinks much about traveling in Model T’s. Just another old car, right? Old yes but at the time of this story a modern form of transportation. In old photographs they look pretty large, certainly taller than the average man but compared to your nice SUV pretty small inside. The front seat could barely hold two adults and the rear not much larger. Mechanically they were pretty robust. They were built of steel and could take a great deal of exterior punishment. Someone like my grandfather could fix nearly any part of it. It came with a tool box with a couple of wrenches and you could add a hammer, some baling wire, clevis pins and cotter keys, a piece of leather for the fuel pump if it failed and the odd nail. A tire patching kit which you would definitely need, spare tire(s) jack and a can of lubricating oil. Those things were about all you needed to solve most problems.

Most importantly they didn’t have brakes as we know them. Breaking was done by shifting into low gear. A Model T Ford had only two gears high and low. When got off the gas you shifted into to low gear to slow the car The clutch was actually the primary braking system strange as it may seem today and without too much ado suffice it to say braking was a sort of multi-tasking operation which involved three pedals, the handbrake which was also a gear shifter and two levers on the steering column, one which slowed the motor electrically and the other the throttle. I’ll let you imagine how all this was done simultaneously. It was akin to a circus act and was very dangerous especially on a downgrade. Add some mud or rain and you could become just a large roller skate sliding faster and faster no matter what you did at the wheel.

Shannon hill, on the down hill side was well known in the Arroyo Grande area for the number of deadly wrecks that occurred at the bottom. It’s still there today and is no problem for a modern car. My father who grew up in the little house at the foot of it was well acquainted with racing to the wrecks and pulling damaged people out of those smashed up old cars.**

They chose to travel up the State Highway 1, today’s 101 because the road through Cuyama was still just a two track dirt, unimproved road. There were no gas stations along the way and though it led directly to Taft where he could perhaps find work it was decided to go around by way of the the highway leading east from Paso Robles, today’s Hwy 46. At the time it had no official name. It was a gravel road east of Shandon al the way through the Lost Hills to Blackwells Corners and then due south to Taft where there might be work. Blackwells Corner is, of course famous for the last place James Dean put gas in his little race car. A dubious distinction to say the least. Dean had less than a hour to live until Mister Turnipseed ended him.

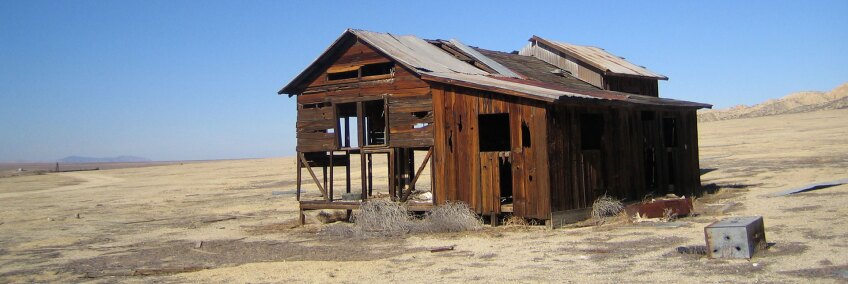

The entire trip was notable for the fact that there was nothing that wasn’t tan or brown and usually covered with a fine sandy dust that came from the incessant blast furnace wind so hot that every living thing was in a state of perpetual dryness. The wooden window frames on houses would dry and shrink until it seemed there wasn’t enough newspaper on earth to stuff all the cracks. There was no paint that could stand the heat in the summer and the cold of winter. Dreary isn’t a good enough word to describe those wishful oasis, the end result of a man’s ambition.

Traveling by night out there you might as well have been on Mars. It was so dark out that there was nothing to be seen but the occasional tiny light in the far distance that marked one of the few ranch houses where cattleman desperately tried to scratch out a living on huge ranches which had little water, shade or permanent pasture. Droughts were frequent and devastating and as the depression advanced even those lights would disappear. Sheepherder’s abandoned wagons along the road would be one of the few pieces of evidence that anyone had ever lived among the Russian Thistle.

All along the Kettleman, Lost and Elk Hills from Avenal to McKittrick you could feel the desperation of those that lived there in hard times. Wives ended their own lives by suicide, so desperate for company that taking your own life seemed almost necessary. You could travel fifty miles and see nary a soul. At the end of the twenties it was still a two day trip to buy groceries.

There was no AC of course. You could push the bottom half of the windshield up and lock it if you were desperate for a little cooling breeze but you had to face forward into the blast furnace of wind. No wind wings and the rear windows didn’t roll down. Mom said they would soak a towel in water and wear it around their necks to cool off. Grandpa and uncle Marion were they only drivers and both had bad backs from heavy labor so once in a while Bruce would ask Eileen to hold the wheel and he would get out and walk. The cars were only able to make walking speed going uphill anyway. Mom and aunt Mariel would squeeze out in the space behind the front seats and ride the running boards or lay out over the fenders. Kids weren’t so precious then and could mostly fend for themselves.

Grandpa and grandpa and their children knew it well though for as bad as it was, it was filthy with oil. It was the only reason to live out there and as grandpa once said the whole region was nothing but a “Hellhole.” They had moved from one to another for twenty years and with the coming of hard times in the oil patch perhaps there was some hope that life back on a ranch would be better.

Mom said bouncing along in the back seat with the dust and noise and temperature spiking the thermometer made it the most miserable trip she ever took. She said that while stopped to let the cars cool she was sweating so much, the heat made her dizzy and she put her hands behind her head as girls will do and was fluffing her hair trying to get her neck to cool when she got a look from grandpa who grinned at her, lifted his cap and ran his handkerchief over his shiny bald head and said, “You should have a bald head like me.” That made them both laugh. She surely loved her father.

Give some thought to how it was to ride along on the trip which lasted three days in a car that could only do about 25 MPH on the dirt and gravel roads of the time. Crossing the Kettleman and Lost Hills, speeds were just 4 or 5 miles an hour on the many grades and hang on for dear life on the down hill and all with many stops to top off the radiators and let the motor cool and perhaps add a little oil.

It was all taken in stride though because to my grandparents who were both born before the automobile it was all quite modern and needed no comment or complaint.

Like all siblings the two girls who were barely a year apart fought. “Don’t touch meee, mom he touched me” was a frequent refrain. the girls were sneaky enough but they said the worst was uncle Bob who wasn’t ten yet and liked setting off his sisters. Bruce and Eileen treated this with good humor. Neither one was inclined to fight with their kids and all their children later said their parents never laid a hand on any of them.

When they could they stopped for sodas or fresh fruit from stands along the highways. There is nothing like opening the cooler on the service station porch and dipping your arm into the ice water and fishing around for just the right soda pop. Might stick your face in too. There is also the great pleasure of slipping an ice cube down the back of your brothers shirt.

They were a tight knit little family. They followed the wells and sometimes changed houses or towns as oftenas a month or two. The depended on each other to get by and they remained that way all their lives.***

There was no work in Taft, Maricopa or any of the other fields around what was known as the “Westside.” There were forests of rigs simply sitting idle so they turned east around Buena Vista lake* and headed for Bakersfield and the Kern River fields around Kerndon and Oildale. When you’re on the road headed for a new place spirits rise, things seemed possible, grandpa had worked those fields and knew practically everyone there but again his hopes were dashed. More idle wells, the people he knew had moved on just as he was, scrabbling for a job, families to feed, following the inevitable ups and downs of hope.

Bruce and Marion wheeled the two Fords out onto highway 99 and headed north up the valley. Money dwindling, hope lying exhausted on the floors of the cars and the kids tired and cranky the families rolled up the finest highway in California. Completely paved, the 99 was easy driving as they passed through all those little towns that sing a song of Californias agricultural heritage, Famoso, Delano, Tipton to Tulare, Kingsburg and Fowler to Fresno, click, clack the hard rubber tires tapping out a tune of the road as they bumped over the joints in the concrete roadway. After Fresno it was back to the old home, The house where my mother was born in 1918, just 23 miles more.

* This link below will take you to the story of how Barbara met George. The Milkman in four parts.

https://atthetable2015.wordpress.com/wp-admin/post.php?post=5632&action=edit

**Family letters, link below.

**File under Grief, link Below

***Family letters, link below.

Michael Shannon is busy telling the story of his California family.

Four Men

The long polished Mahogany table as seen through the little nook off the living room, an opening on the left where the swinging door to the kitchen stood propped open with a fold of newspaper and at the end of the room a window with its Venetian blinds open looked out to the side of Mrs Lake’s home stuccoed in beige and with a little imagination you could see a long stretch of featureless desert sand. Before the glass, sat four grown men.

I could watch them at a distance and have always wondered what it was of which they spoke. Hand on fist I would sit on the little brick hearth of my grandparents home in Lakewood and try to listen.

Gathered together around the every day tablecloth that would be changed for Thanksgiving dinner later that day sat my Grandfather Bruce Hall. A man who had labored nearly four decades in the oilfields of California. He was now the superintendant of drilling for the state of California. From oilfield roustabout to the top of the heap at Signal Oil and Gas. He wore his rumpled, baggy khakis and a white long sleeve shirt with the collar open and the sleeves rolled halfway. Spectacles over the lower half of the nose, his bald head encircled by a fringe of hair smelling of Wildroot. He seemed to me to be perpetually tired. He’d already had the first of the heart attacks that would in a couple of years kill him. A lifetime of filterless Chesterfields, one of which, smoldering he held with three fingers, idly scraping the ash from on the edge of the ashtray, a green baize bag filled with bird shot and a shallow brass bowl. He leaned forward on his elbows a half smile on his face.

My Dad sat next to him in his ever present flannel shirt and blue Levi’s his uniform of sorts the mark of a farmer. He was forty three. He sat in his customary pose, elbows braced on the table a half smoked cigarette in his right hand pinched behind his upper knuckles, I can’t remember ever seeing him sitting any other way. At his elbow a half filled bottle of bourbon being occasionally lifted with the comment, “Another drop?” No ice either, whiskey straight no frills, or as my dad told me, “Ice dilutes and pollutes the Bourbon. Bartender puts it in to short the pour.”

There was a glass at each mans hand, no fancy fat little crystal glasses, grandma had them but they mostly sat in the sideboard gathering dust. No, these man drank from kitchen glasses and in those days it was likely a jelly jar, not the canning Mason or Kerr but the old fashioned one that came from the Jewel Tea truck, full of, and always in that household, blackberry jelly, the kind that you had to pry the lid off with a church key. Practical men they were but at the same time would never drink straight from a bottle. Class of a sort.

Uncle Ray sat at grandpa’s other hand. His dark blue shirt with the mother of pearl buttons marked him as a cowman. In his late forties he was a little on the portly side, the shirt held in with a plain leather belt and a small not so fancy buckle. His old fashioned black levi’s turned up at the cuff a good four or five inches covered most of what were hand-tooled cowboy boots for thats what he was, a dyed in the wool, genuine cowman who could fork a horse as good as any. Better than most really for he was known through the Sierra Nevada as “Powerhouse” after, on a bet, put his horse Brownie over the side of the hill at the Kings river penstocks and rode her almost straight down as if it was nothing. A feat of horsemanship that gave him the name. If you ever get up there you’ll see what I mean.

I remember him most for his laugh, a sort of lung deep basso cackle, really indescribable but still one of the greatest laughs I have ever heard. He didn’t hog it either it was as if it was just idling down in his throat ready to spring to the surface on any occasion.

Ray Long was such an original cowman, at that time already a vanishing breed that he had taken on the characteristics of the horses he rode. He was missing the molars on one side of his jaw and when he tipped his head back to laugh he looked just like a horse did. Horse laugh my dad called it.

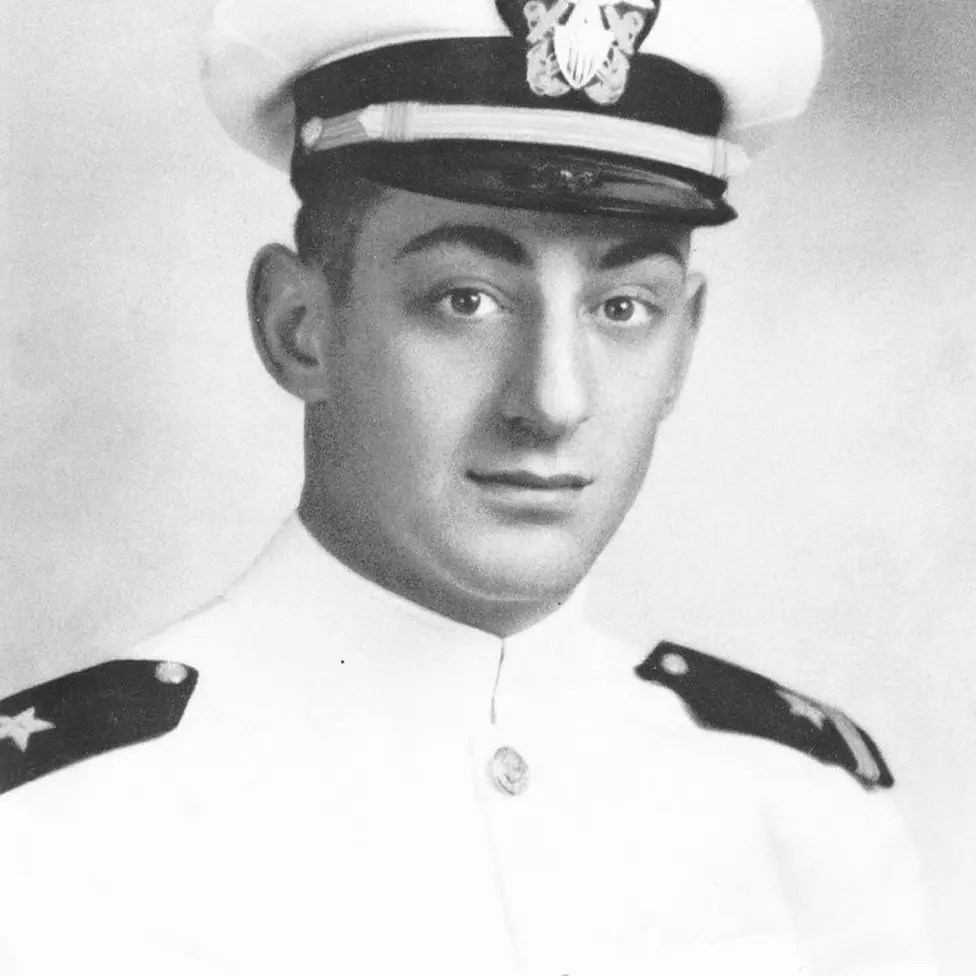

The fourth that made up the quartet was my uncle Bob, Robert Preston Hall. At thirty five just a youngster. My mother’s youngest sibling, the only boy of that generation. He grew up with two older sisters and one younger who adored him. My aunt Patsy always said he was as caring as any parent.

He leaned back in his chair right arm hooked over the back with an elbow, his legs crossed at the knee. His white shirt collar unbuttoned had short sleeves, something I never saw the other three wear, ever. Cigerette pack in the pocket, he held one in is right hand. His jet black hair, slicked back shone in the light and sitting on his nose, old-fashioned steel rim, round spectacles. Topping it all off, he wore a thin mustache, the kind we used to call the “Boston Blackie.” He had an elegant long straight nose and a family trait inherited from grandpas’ family, Jug Handle ears. Mom said they were like airplane flaps and would slow you down when you came in for a landing.

Uncle Ray loved to tease and used the family ears as nicknames for one of his sons and me. Ears like that, guess they didn’t hurt Clark Gable none. He was an oil man too in his younger days. They had that in common.

They were different looking men really, no two looked alike but they had things in common. They could be absurdly funny and the well jest turned earned high praise in our family. The were men of the land all of them farmers and ranchers at heart with deep roots in the ground. Practical and pragmatic, they wasted no energy on frills. None of them liked to wear suits if they could avoid it and they did at all costs. The best you could get out of my dad was a sports coat and slacks.

They were all good with kids. I have friends I grew up with who still remember my dad handing out quarters at gatherings which meant something in those days. Uncle Ray made you feel like you were a grownup but wasn’t above squirting you with milk while milking either. Uncle Bob had the salesman gift and told me very first dirty joke though it barely made the grade as such.

The thing I most remember is they were grownups who stood for something. Kids were great but still kids. They shared very little about adult life. They did their best to keep all that at a distance to keep you safe. Your were a kid and they were adults, it was important that they kept it that way. They taught much more by example and were pretty content for their children to find their own way with as little guidance as possible.

Once my oldest cousin who was about fourteen and though pretty well of himself sauntered in and pulled out a chair and sat. He interjected some comment into the conversation and they all turned to look at him. No one answered. A moment or two passed as they sat silent until it occurred to him that maybe he wasn’t as old or important as he though and he soundlessly slithered out of the chair and beat a retreat.

They bookended an entire generation from one end to the other. They had seen two world wars, the greatest depression, the Korean War, the atomic bomb and each had weathered severe up and downs in the family.

That thanksgiving saw a dozen kids and five families shoehorned into that little house on Pepperwood Avenue in Long Beach, just about the last time we would all be together. Other than seeing them I really didn’t know what they talked about. I wish I had been older so I could really listen but I wasn’t.

Years have past and the questions were never asked. I had other interests and they were famously recalcitrant anyway in the way men of that generation could be. “Oh, you don’t want to know about that,” my uncle Jackie Shannon once said. I did but he just changed the subject. Every person you will ever know dies with secrets and stories you will never hear. It’s a shame.

Michael Shannon is a writer. He lives in Arroyo Grande, California.

The Good Man

Michael Shannon.

He went to the old sideboard, stained as it was, a few wood chips missing here and there and leaning on it momentarily, he slipped into his right front pants pocket and he drew a key. Fumbling a little with the little piece of brass on the faded purple ribbon he inserted it and slipped the lock and from inside he retrieved the small brassbound wooden box graven with its vague mystical symbols and carefully set it on the cabinet top. With trembling hands, not by age but by emotion, he reverently untied the ribbon that held it shut and with care beyond care he opened it and released, the wonderful soul within that rose and floated as dainty as a butterfly above and for all to see. It shimmered in the light and was God.

For a friend.

Twelve Hour Tour

Chapter 14

Oct 24th 1929

In ’29 Bruce was transferred to the new field up at Elwood. Barnsdall-Rio Grande gave him a raise and he became a field supervisor. The Mesa and Ellwood fields needed men who could whipstock as the wells were being pushed out into deeper water. Bruce was good at that.

Elwood. Goleta Historical Society photo.

Bruce and Eileen moved up to a little wide spot in the road called Goleta. Sometime after the De Anza expeditions, a sailing ship (“goleta”) was wrecked at the mouth of the lagoon, and remained visible for many years, giving the area its current name. After Mexico became independent of Spain in 1821, most of the former mission ranch lands were divided up into large grants. Nicholas Den was granted this 16,500 acre rancho in 1842. The Rancho was named Dos Pueblos for the two Barbarino Chumash rancherias which were on the bluffs above the beaches. Below that was what would become one of the largest oil producing fields in California.

Barnsdall-Rio Grande added the Elwood field to Bruces territory. His skill with whipstock was doubly important because at Elwood there were no actual wells onshore. Every well was turned out into the oil sand under the Santa Barbara Channel.

Goleta wan’t much of a town in the late 20’s but they decided to move closer to the wells because exploration in Summerland was nearly done and his chief job there was to monitor production.

Bruce’s half-brother Marion who originally got him in the job in Casmalia was giving the oilfields another go. Marion and his wife Grace with their son Bill moved in with Bruce and Eileen. The kids were attending Goleta Elementary school. Mariel the oldest was just thirteen, my mother, a year younger and uncle Bob was nine. In the old photos you can see that they are better dressed surely as the result of Bruce’s promotions.

That same year Bruce and Eillen gave my mother a piano. It is, we still have it by the way an upright Gulbranson, it cost the princely sum of $300.00, and I do mean princely. The equivalent sum today would be over five grand. The original receipt calls for ten monthly payments of $30.00 each. As a Tool Pusher or Farm Boss Bruce would have been making as much as ten dollars a day. That was a very high wage for men employed in the oil fields and good pay for any man who worked with his hands.

Derrick and wells, Tecolote Canyon, 1930.

Below the horizon though a financial wave was slowly gathering and like the music played in the movie Jaws, it was building quietly but would soon turn their entire world upside down.

In November the entire house of cards came crashing down. Out of control oil companies who pumped more oil than the public could use. Banks which loaned far more money than they actually had, 650 failed in 1929 and over thirteen hundred by then end of the next year. There was no FDIC to protect your money. Millions of people lost their life savings. Wall street’s frenzy of buying and selling on margin,* the residual cancellations of industrial war equipment and the end of farm price supports put the economy in the tank where it would stay for nearly ten long years. Money that vanishes is not easily replaced. Within a year, 25% of the population was unemployed and completely adrift. Men were desperate for work and just the rumor of a job put them on the road. Children too, they were forced out of families or left on their own because feeding them was a burden to their parents.**

In 1930 Bruce reported to work at Elwood where he was abruptly fired along with his entire crew. Barnsdahll-Rio Grande had pulled in their horns, declared bankruptcy in order to escape their creditors, the banks and private investors. Then they simply walked away from California. It’s leases in Summerland and Santa Barbara were sold, it equipment simply abandoned. Oil companies, finally accepting their fate fell like dominoes. Thousands and thousands of roustabouts, worms, toolies and farm boss jobs evaporated almost over night. Your hard won skills were useless. This pull back on labor was across the board, factories, big farms, the shipping industries all pulled back.

After ten years of continuous employment Bruce’s career was simply yanked out from under him. He called in favors, got on the phone, calling everywhere, every company he had ever worked for, Associated, Standard Oil, Union and every operator from Huntington Beach, Los Alamitos and Signal Hill to the coastal companies and east to the San Joaquin valley, drillers in Oildale, Kern River and the West side and the Elk Hills; Maricopa, McKittrick, Reward and Fellows. There was nothing moving. Drilling for new oil was dead, only maintenance and pumpers had any hope of a job.

Thirty four years old, wife and three children and desperate. He was lucky to land a job with Santa Barbara Garbage Company, slinging ash cans. He rode the trucks standing on the foot plate, jumping off at every stop and hefting the loaded bins onto his shoulder and tossing them up on to the back of the truck as it idled up and down the streets of Santa Barbara and Montecito, two of the richest towns in California. A self-made man humping the garbage of the rich. It must have been galling. His brother Henry said Bruce worked like a mad man. Twelve hours a day, six days a week, sun up to sun down for $16.00 dollars a week, roughly .22 cents an hour. The cut in pay by more than three quarters put them on a collision course with poverty. It came pretty soon.

Eileen finally took the desperate measure and I mean desperate measure of going to the government office in downtown Santa Barbara and applying for relief. Under President Roosevelt’s series of assistance programs, established by the New Deal, provided federal funds to state and local governments for direct relief to the unemployed, including cash payments and food assistance. These programs aimed to provide immediate assistance to those who were unemployed, impoverished, or facing economic hardship. Like any good idea it was soon run by petty bureaucrats who wielded absolute authority over people who were guilty of nothing except being poor. They didn’t want to be poor and were shamed by the very thought of asking for help.

Just as today, those better off considered thee programs as a “Giveaway.” Relief had strict guidelines for eligibility. To meet qualifications the applicant had to fill out a questionnaire and be evaluated as to need. The Halls had the need alright. Three kids, a wife and a husband with a very low paying job which he could lose at any time. There were thousands of others who would gladly take it if they could. They stood on the steps of the company office every day, smoking, nervously, hoping for the smallest break. Mostly they would get none.

For a proud family, which we still are it was agonizing for my grandma to sit in the chair and “Beg” for help. Beg, a word that was loathed by my grandparents. Grandpa Bruce had pulled himself up by his bootstraps and was rightfully a prideful man. There is no adjective strong enough to describe how it must have felt to sit in that straight back, hard bottom chair, in front of the desk where the woman who would decide your family’s fate sat.

The conversation was short. “You qualify for food and rent assistance with just one stipulation,” she said. “Your husband will have to sell the car.” My grandmother couldn’t believe her ears. “But he needs the car to go to work,” she said. The woman looked up from her paperwork and said, “Thems the rules. He has to sell the car.”

When grandma Hall told that story it cinched a hatred for the government that still exists in our family. It’s not that it can’t help people in need but the way they do it.

My mother remembers them talking in quiet tones at the kitchen table that night. They’d sent the kids out of the room for they lived in a time when children were seen but not heard. Mom was scared because she didn’t understand what was happening. Her parents were as kind as they had always been but she said the kids knew something scary was happening. Bruce and Eileen were tense and very quiet. After ten years on the road with oil this was brand new territory. Grandpa had the assurance of a man who labors at his trade but the thought of losing all of that, though never said out loud had changed the dynamic of the family. Grandma and grandpa never had a harsh word for one another but to see her mother with tears was something she never forgot.

The only thing they thought possible was to join the family in Madera on grandpa Sam Hall’s ranch where they could at least eat and live under a dry roof.

So, they packed up what they could fit in and on the car, arranged for a friend to haul the piano and simply left the rest, furniture, dishes and all and pulled out for Madera.

The Halls on the road to Madera. From left to right, Mariel, Robert, Barbara, Eileen, and Bruce. In the rear uncle Marion. 1930 Photo Grace Williams. These old photo make people look older than they were. Bruce and Eileen are both thirty four. Grandpa has his foot on the bumper to relieve his back, a problem he had all his working life.

*In the 1920s, buying on margin meant investors could purchase stocks by paying only a small portion of the stock price with their own money, and borrowing the rest from a broker. This allowed them to control a larger investment than they could otherwise afford, potentially magnifying profits. However, it also significantly increased the risk, as losses could exceed the initial investment if the stock price declined. When the broker called the margin the buyer had to make up the difference between the money spent and the difference owed the broker. It was a dangerous investment strategy if the buyer was unable to make up the difference. In 1929 it was a financial disaster.

**Wild Boys of the Road is a 1933 pre-Code Depression-era American drama film directed by William Wellman and starring Frankie Darro, Rochelle Hudson, and Grant Mitchell. It tells the story of several teens forced into becoming hobos. The screenplay by Earl Baldwin is based on the story Desperate Youth by Daniel Ahern. In 2013, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically. Available on Apple TV.

Michael Shannon is a writer and former teacher. He writes so his children will know their history.

Whats’s in a Name.

By William E. Lye

The Secretary of defense has ordered the renaming of United States Naval ships as follows.

- The USNS Medgar Evers. The Evers will be recommissioned as the USNS Theophilus Eugene Connor (1897-1973) Eugene “Bull” Connor gained infamy during the spring of 1963 as the heavy-handed Birmingham police commissioner who turned power hoses and police dogs on the black demonstrators led by Martin Luther King, Jr. Bull Connor and Birmingham symbolized hard-line Southern racism. Connor’s actions received national and international media coverage, which dramatized the plight of black people in segregated areas, giving the civil rights movement much-needed attention. After viewing television reports of the fire-hose and police-dogs episode, President John Kennedy said, “The civil rights movement should thank God for Bull Connor. He helped as much as Abraham Lincoln.”

- USNS Thurgood Marshall. The Marshall will be renamed the USNS J. Robert Elliot. Elliott criticized his own party’s president, Harry S. Truman, and federal legislation to ban lynching and eliminate the poll tax, and he had opposed creation of a Fair Employment Practices Commission. Elliot criticized Democrats of southern states who opposed the civil rights act. In his 1952 Georgia House campaign, he expressed dissatisfaction with attempts to end the all-white primary: “I don’t want those pinks, radicals and black voters to outvote those who are trying to preserve our own segregation laws and our sacred Southern traditions.”

- USNS Harriet Tubman. She will be named the USNS Thomas McCreary. McCreary, a slave catcher from Cecil County, Maryland. Proclaimed a hero, he first drew public attention in the late 1840s for a career that peaked a few years after passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Living and working as he did at the midpoint between Philadelphia, an important center for assisting fugitive slaves, and Baltimore, a major port in the slave trade, his story illustrates in raw detail the tensions that arose along the border between slavery and freedom just prior to the Civil War.

- USNS Ruth Bader Ginsberg. The proposed ship will have its name changed to the USNS Roger B. Taney. Taney, an American lawyer and politician who served as the fifth chief justice of the United States, holding that office from 1836 until his death in 1864. In the Dred-Scott decision, Taney’s court declared that all blacks — slaves as well as free — were not and could never become citizens of the United States. The court also declared the 1820 Missouri Compromise unconstitutional, thus permitting slavery in all of the country’s territories. The case before the court was that of Dred Scott v. Sanford

- Other proposed names to be deleted, Dolores Huerta, Cesar Chavez and Lucy Stone.

- The Congressman John Lewis class of ships one of which was the USNS Harvey Milk. The class to be renamed for James Oliver Eastland who was a segregationist Senator and led the Southern resistance against racial integration during the civil rights movement, often speaking of African Americans as “A degraded and inferior race”. Eastland has been called the “Voice of the White South” and the “Godfather of Mississippi Politics”. His famous quote on politics in answer to a reporters question was. “I run on two things, bridges and “n*****s, ahm for one and agin t’other.”

Chief Pentagon spokesman Sean Parnell said in a statement that Hegseth “is committed to ensuring that the names attached to all DOD installations and assets are reflective of the Commander-in-Chief’s priorities, our nation’s new history, and the warrior ethos.”

“Our military is the most powerful in the world – but this spiteful move does not strengthen our national security or the ‘warrior’ ethos. Instead, it is a surrender of a fundamental American value: to honor the legacy of those who worked to build a better country.”

Although the Navy has renamed ships for various reasons, name changes are an exceptionally rare occurrence, especially after the ships have entered service.

The Navy is made up of sailors from every state, political party, ethnicity, sex and religion. Navy men and women represent the diversity of all Americans and for the sea going contingent particularly treasure the traditions and affection for the ships they serve on.

You could have a long and serious discussion on the “Whys” of military bases and ships but politics intrudes for all kinds of nefarious reasons having to do with who votes for you the political office holder. Traitorous Confederate Generals get a name though they and their political class fostered a war that killed nearly eight hundred thousand American boys and men. The first black associate justice of the Supreme Court, a highly praised legal scholar, Thurgood Marshall is erased over what should be the motto of this country, the most diverse on earth since the Romans. DEI, Diversity, Equity and Inclusion which perfectly describes the goals this country has pursued since it’s very beginnings. This is someones personal fever dream of hate and divisiveness. Some times we stumble as a people and fall down but the idea that the pipsqueak in the Pentagon can erase, not just a paragraph in a history book but the lives of people who changed this country for the better because he thinks that his Moral Superiority derives from the color of his skin or his belief in a vengeful God.

The writers point is to demonstrate the utter absurdity of the administrations goal of canceling all of whom they don’t like. Remember the minority, in the end, rarely prevails.

The names of the propose ships are a fiction used to prove a point.

Willian E. Lye is a writer who cherishes the title of Iconoclast given to him by Janine Plassard one of the worlds greatest educators.