Written by Michael Shannon

A historian seeks the truth of it. He is neither blinded by the glare of opinion nor does he ever stop seeking a final answer which he knows in his heart is not or ever will be there. He must always dig deeper. His life is to live in worlds which no longer exist. His life is to parade before mankind the true blocks that built the world we live in.

My friend the historian has pawed through the dustbins of scrap, piecing together the puzzle of lives lived. Letter, journals, documents, film are all grist for the mill. A fabulist he is not.

He understands that there is never a final answer. There is always something to be discovered and his hope is the honour will be his. That is his calling.

Not long ago in a comment string on an article he posted, someone commented that what he said was interesting but not written by a “Real” historian. A “real” historian, which implied he was not.

I’ve been thinking about the comment and the not so subtle dig it implies so I though I’d explain what a real historian is.

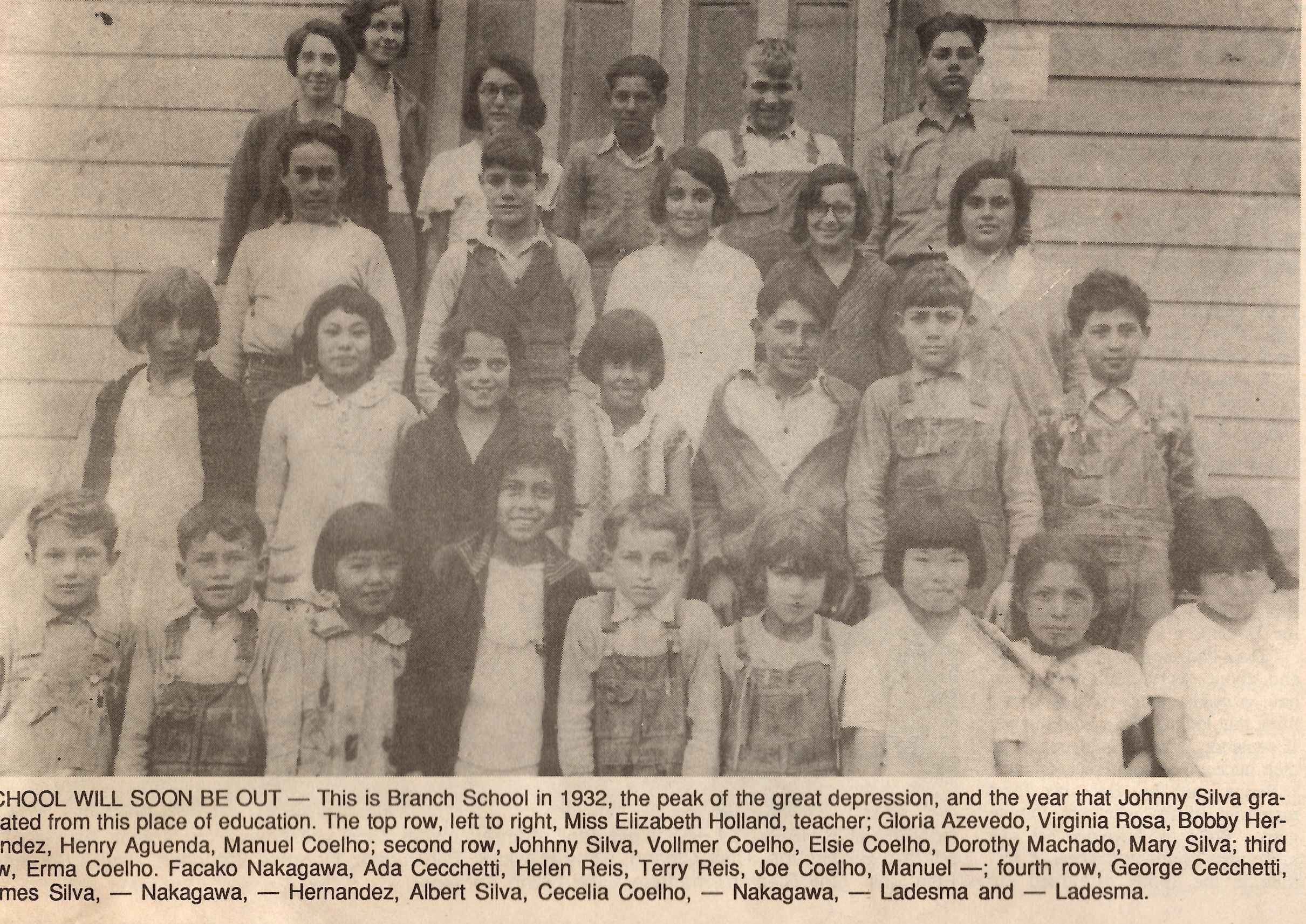

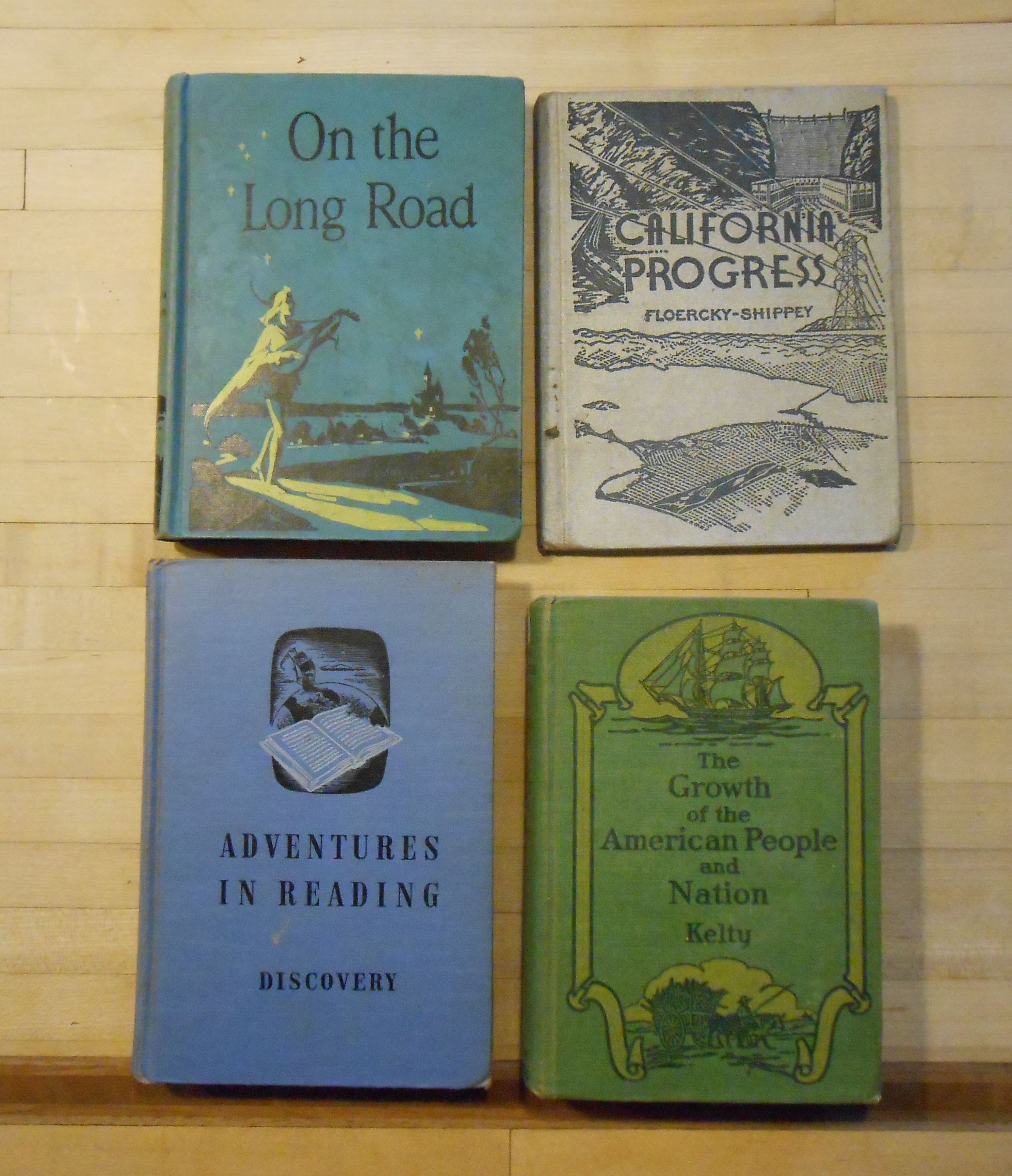

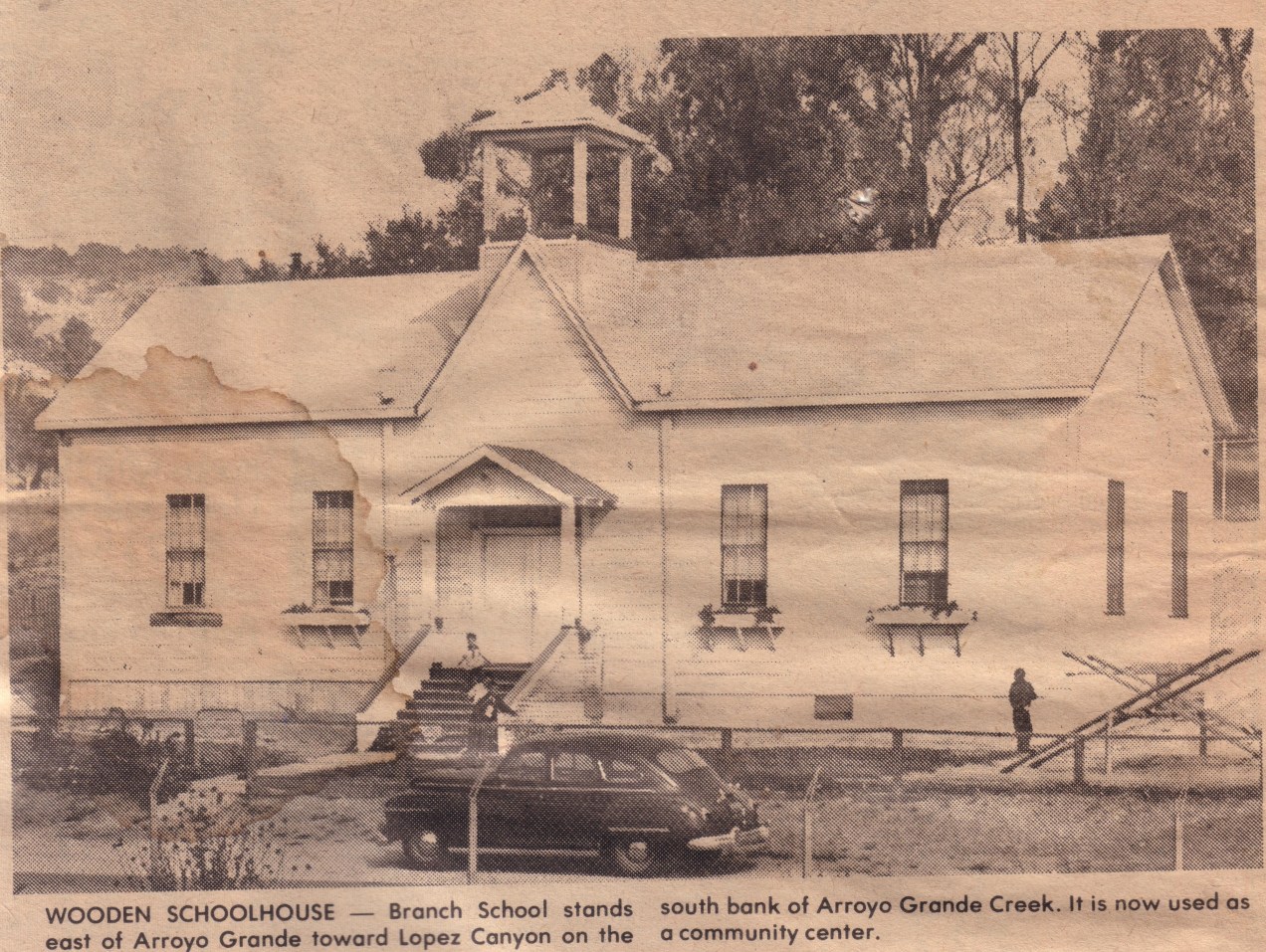

You are. Did you keep your grandmothers Christmas cards? How about your mothers letters to her sister. Perhaps the journal your great uncle kept when he was stationed in Vladivostok during WWI. Do you still have the box with some black and white unidentified photos, the ones with the deckled edges and a coffee stain? Does it have an old crinkled embroidered handkerchief and at the bottom and a deed to the ranch made out in 1924. Do you still have your high school yearbook? How about a set of Compton’s Encyclopedia from 1930. All of that, my friend is history. Keepers of history long for those things. Mundane objects are the things history is made of.

True history which is known to all “real” historians is made up of the things that did not get thrown away. We know of the war between the kingdoms of Elam and Assyria because a record of the conflict was kept and survived nearly three thousand years buried in the sand of southwestern Iran. In Great Britain the site of the Roman fort at Vindolanda, a part of Hadrian’s Wall built to keep illegal Picts from what is now Scot Land from entering Roman Britain. Just like today its cost was enormous and it didn’t work.These finds record military expenditures; daily bookkeeping which hasn’t changed in nearly 1,900 years which you would recognize if you ever served in the military, have been found. From it we learned that Roman soldiers wore underwear, something completely unknown until today. The documents are personal messages to and from members of the garrison of Vindolanda, their families, and their slaves. Highlights of the tablets include an invitation to a birthday party held in about 100 AD, which is perhaps the oldest surviving document written in Latin by a woman. It features her signature, the first known example of a woman signing her name, Claudia Severa. The commander’s wife was writing to Sulpicia Lepidina. How different is that than your grandmothers invitations. You can easily see it’s the same thing. That is its historic significance.

Those of us who watch movies or read novels must learn the difference between story telling and historical fact. Screen writers play fast and loose with history all the time. The old saying that “Facts should not get in the way of a good story” are absolutely true Unless you are a historian.

Consider some favorites. Old Braveheart, William Wallace never saw a kilt in his life. Thomas Rawlinson, an English ironmonger, who employed Highlanders to work his furnaces in Glengarry near Inverness invented the one you are familiar with in the early eighteenth century, around 1710. Finding the belted plaid wrap cumbersome, he conceived of the “little kilt” on the grounds of efficiency and practicality, as means of bringing the Highlanders “out of the heather and into the factory.” However, as Dorothy K. Burnham writes in Cut My Cote (1997), it is more likely that the transformation came about as the natural result of a change from the warp-weighted loom to the horizontal loom with its tighter weave. After the battle of Culloden (1745) which Jamie Frasier barely survived, wearing the “Wee Kiltee,” it was outlawed By the British overlords. Luckily moviegoers don’t care that Braveheart died horribly in 1305 over four centuries earlier.

William Wallace didn’t paint his face blue either. Where did the idea that the Picts painted themselves blue originate? Julius Caesar once noted that the Celts got blue pigment from the woad plant and that they used it to decorate their bodies. Pict was a name coined by the Romans to describe the Northern tribes who covered their bodies in blue woad to camouflage and perhaps to intimidate: Picti means painted people in Latin. It is likely that the Picts were descended from the native peoples of Scotland such as the Caledones or Vacomagi who lived in modern-day northern and eastern Scotland about 1,800 years ago. Picts is merely a descriptive term. William Wallace and the Scots wore blue face paint in Braveheart, not because it was historically accurate, but because the filmmakers liked the idea of it. Braveheart certainly did not have sex with the English Queen out in the woods. Did Queen Eleanor have the habit of wondering around in the darkling woods of a night. Certainly she did not. If she wanted a child by Wallace she would have removed her Wimple which women wore to cover their hair lest the sight of it turn men into savage wanton beasts. She died fifteen years before Wallace’s revolt.

Henry the VIII’s second wife Ann Boleyn was executed, her head severed with the sword of a French executioner because she was an adultness. At least that is what we learned in “The Tudors.” Think about this, Henry the VIII was 6’2″ and weighted 210 pounds when he was in his twenties. The man who played him in the series is 5’9″ and 155 pounds. Quite a difference, yes? The simple truth is, Henry was a Tomcat, adultery was his hobby. Anne’s sister Mary was one of his mistresses, pimped out by her own father Thomas Boleyn the Earl of Wiltshire and the 1st Earl of Ormond. These were nasty ruthless people. What Henry was, was fixated on having a male heir to the throne. The Tudors had overthrown the York family by killing King Richard the third who was the last of the Plantagenet dynasty that had conquered Britain in 1066. Henry felt a little shaky on the throne. English barons were a testy and power hungry lot and they could turn on the king in an instant. With the help of Bishop Cranmer, the head of the church, charges were trumped up and the lovely Anne bared her “Little Neck,” she actually said that to the executioner before the chop. She went to the block, dressed in a white shift, her hair shorn and her feet bare. Henry’s only concession was to allow the sword rather than the axe. Royalty was not to be beheaded by axe or an Englishman, hence the Frenchman. Likely we wouldn’t be at all interested in her story except that her daughter grew up to be the most famous British monarch of all. Elizabeth the first. The virgin Queen, though that too is in serious doubt. The virgin part I mean.

The archives kept in the British museum document Annes trial and her indictment but also contain the personal letters between the principles which show without a doubt that she was completely innocent of anything except, apparently, the capital crime of having a girl baby.

Willian Shakespeare did not write his plays. That idea, which has persisted for decades was good enough to make more than one movie. We can start with the fact that his life in London is very well documented. There are the bills of lading for the material that he used to build the Globe theater. There is the building permit for the same. There are copies of the original documents themselves with his name on them The main argument, in the absence of such “proof” of authorship, skeptics have posed the question: How could a man of such humble origins and education come by such wealth of insight, wide-ranging understanding of complex legal and political matters and intimate knowledge of life in the English court? Shakespeare’s supporters emphasize the fact that the body of evidence that does exist points to Shakespeare, and no one else which are written in his own hand. This includes the printed copies of his plays and sonnets with his name on them, theater company records and comments by contemporaries like Ben Jonson, Samuel Boswell and John Webster, men of letters who actually knew him. Doubts about Shakespeare’s authorship and attempts to identify a more educated, worldly and high-born candidate reveal not only misguided snobbery but a striking disregard for one of the most outstanding qualities of the Bard’s extraordinary work—his imagination.

Who can doubt that an intelligent man, even one with limited education, not use historical works as background for whatever his bountiful imagination seeks to follow? Provable historic fact are the foundation of his plays, the same as it would be if he was writing today. Consider Samuel Clemens, one of Americas greatest writers. Fifth grade education in he backwater town of Hannibal, Missouri. Charles Dickens also left school at age twelve and I’ve seen no movement to discredit either.

In the end, the Puritans, yes those Puritans who figure in our American history tore down the Globe theater and banned all productions of any play including Will’s as being devilish and depraved. Puritans condemned the sexualization of the theatre and its associations with depravity and prostitution. Puritan authorities shut down English theaters in the 1640s and 1650s—Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre was demolished and copies of his plays were burned. That is an example of history that is not made up.

The Puritans ruled England and early white America for a time. When you read your high school text book, there is no mention of the fact that they banned Christmas. Sometimes historical facts don’t fit the narrative do they? Inconvenient but provable historical fact. No Christmas for you. Maybe they had a point. Americans spent around 178 billion dollars on Christmas this year, nearly a thousand dollars per person.

The sainted “Boy General” George Armstrong Custer was in real life impotent because he spent a lot of time with prostitutes even after marriage. Gonnorea will do that to you. The Mercury used to treat it did his mental faculties little good. He demonstrated during the Civil War a sort of demented courage which the generals encouraged and rewarded him for with stars and high praise. He proved to be no tactician though and his skill was the same as any attack dog, he just went straight at the foe. After the war his career centered around the occasional Indian massacre, more cheating on his wife embezzling from the Army and in the end these skills or failings, call them what you will got him savagely killed which historians today say was his deserved fate. The whole story of the Greasy Grass fight was told ad infinitum by those same white men who ran the country. It apparently never occured for anyone to ask the winners who, when they were asked had quite different storys. He may have made it to the hill like the painting shows and in fact none of the warriors or warriorettes, yes the woman fought too even knew it was him. He was likely knocked off his horse by Buffalo Calf Road Woman and shot twice. Buffalo Calf Road Woman rode her horse into the Little Bighorn battlefield and struck Custer on the back of the head with a club. Custer, who was already injured with a shot to the chest, was knocked off his horse and died there. A bullet to the left temple did him in.

The gruesome details of the story from the elders say that following that encounter, another warrior woman speared him in the side with a saber in order to be a part of the slaying, and other women warriors took sewing utensils and stuck them in his ears. George Custer was an evil man in the eyes of the indigenous tribes.

Sticking him in the ears would prevent him from hearing them coming in the afterlife. Many warriors mutilated the Wasichu after the battle, but because Custer was labeled as an evil spirit, they left his body intact. White men said it was out of respect, Lakota and Cheyenne begged to differ.

There is some conjecture that the body may not have been him. Two days, stripped naked in the blazing sun meant that very few bodies were ever identified with certainty. History is murky that way.

The Crow scout Half Yellow Face told the colonel before they rode down upon the village,”You and I are going home today by a road we do not know.” He was correct.

When I was still teaching high school I heard from my mainly male students about their love of the Kurt Russell version of the Tombstone legend. They were adamant that the Earp legend was hands down true and accurate. They would accept no argument. What they knew was what the Earp and the screenwriters told them. Because Earps history is relatively recent, unfortunately it is also pretty well documented. Over two dozen films have featured Wyatt Earp, actually that would be Wyatt Barry Stapp Earp, a name that doesn’t easily fit on a theater marquee. Writers play fast and loose with “facts” all the time. What documented history knows and can prove is this; He was by turns a lawman, stage robber, horse thief, gambler, pimp, brothel keeper with his brothers, two of his wives were prostitutes and is definitively known to have killed two men, one a town marshal. At the shootout, eye witnesses state that he wore a Mackinaw coat not a long black overcoat ala Kurt Russell. He also didn’t carry a pistol in a gun-belt but in his pocket as was his custom. Perhaps the testimony of men who knew him in Tombstone sheds a light on his personal history. Roy Drachman would later write: “I don’t remember when Wyatt Earp began to be looked upon as some kind of hero. That was not his image around Arizona then, where many people knew and remembered him well. I never heard anything from those folks about any of the good or great deeds that he is supposed to have done. I think he just made them up for his biography which is nearly all lies anyway. He was a simply a survivor at a time when some of his close friends and relatives weren’t so lucky in avoiding a violent death.” Lastly, John Ringo had no education at all and did not speak Latin. Holliday didn’t either.

Likely not many men have noticed that few women are featured in the teacher’s history book. That’s something you might wonder about.

Consider, before you comment on my friends historic credentials, most people have only a single high school credit in US History, taught from a text compiled by a college professor and likely written by teaching assistants, cobbled together from many pieces and passed of as definitive “Truth.” 50% of U.S. adults are unable to read above an eighth grade level book with complete comprehension. 33% of U.S. high school graduates never read a book after high school. 80% of U.S. families have not purchased a book this year. (2025) The current chief executive does not. According to his family ever been a reader a fact which he demonstrates daily. Knowing this, it seems to me that folks should be very careful about who, what and why the so called facts they offer up in any criticism of “Real” historians.

Perhaps the best example there is, is that until recently everything you know about ancient Egypt came from Victorian Era amateur archeologists. All of them educated white men who had no background in the very long arc of Egyptian history. Not one asked an Egyptian. Until recently nearly all you knew about King Tut, Akhenaten and his wife Nefertiti, and the other Pharaohs was written by these English gentlemen. What you know of the city stae of Troy was written by a German.Notwithstanding the beauty and the glory of that which was found in their tombs the real treasure were things like your grandmothers post card. Found in digs all over Egypt are payroll records for the pyramid builders, personal letters, diaries and business accounts. Those mundane objects are the real historical record.

Our friend the local historian knows where knowledge lies. He has written, studied and taught nearly his entire lifetime. He deserves credit for what he says. Do not take him lightly.

The phrase, “I only want to hear what I already know” was never uttered by any Historian.

History is a growing thing, it changes constantly as new things are discovered. As my sainted father was wont to say, “Don’t believe most of what you read and only half of what you see.” Look for it yourself, it’s the only way to know. History is thick, dense and very tasty. It explains a lot for those that seek it.

This particular historian, with his inquisitiveness and his joy in pure thought shine through, and they have captivated me. In a time when parts of our society, particularly political leaders are trying to freeze false historical narrative in amber, glorifying a time that never was, it’s more important than ever to get down on your knees and dig in the pig pen for that lost diamond.

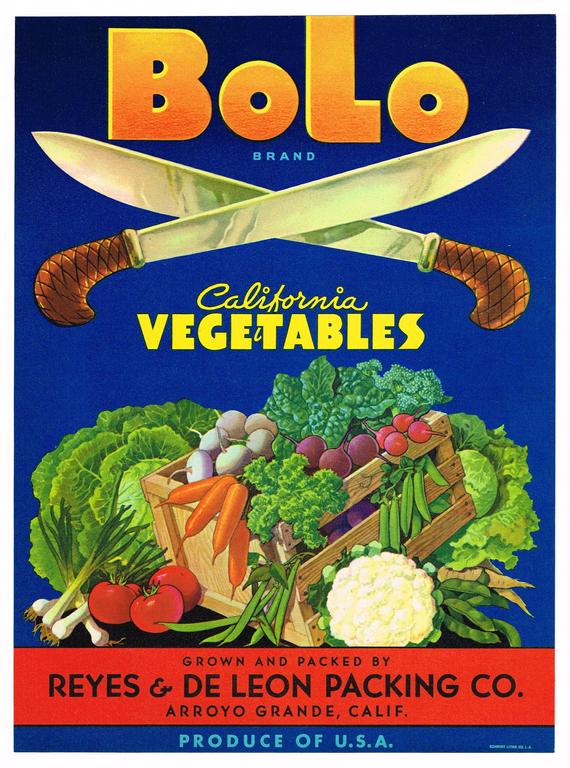

Michael Shannon is a World Citizen, Surfer, Sailor, Teacher, Builder and Story Teller. He lives in Arroyo Grande, California, USA. He writes for his children.

E-Mail: Michaelshannonstable@Gmail.com

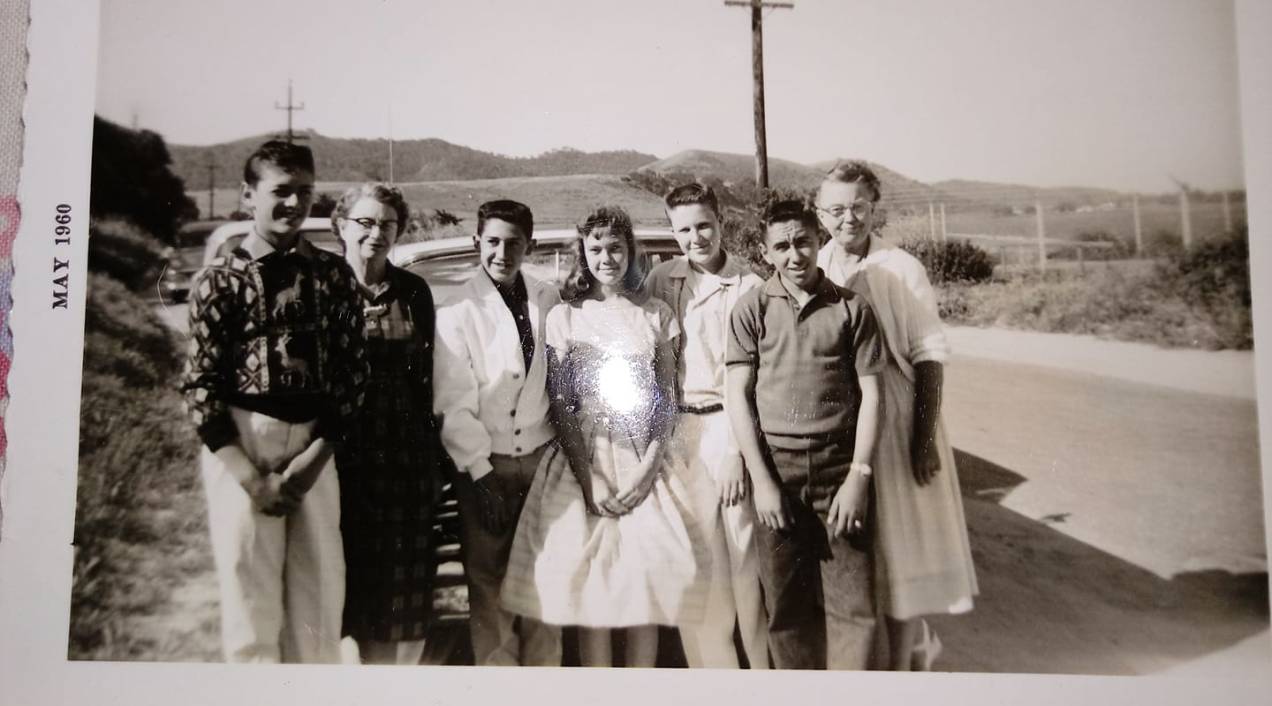

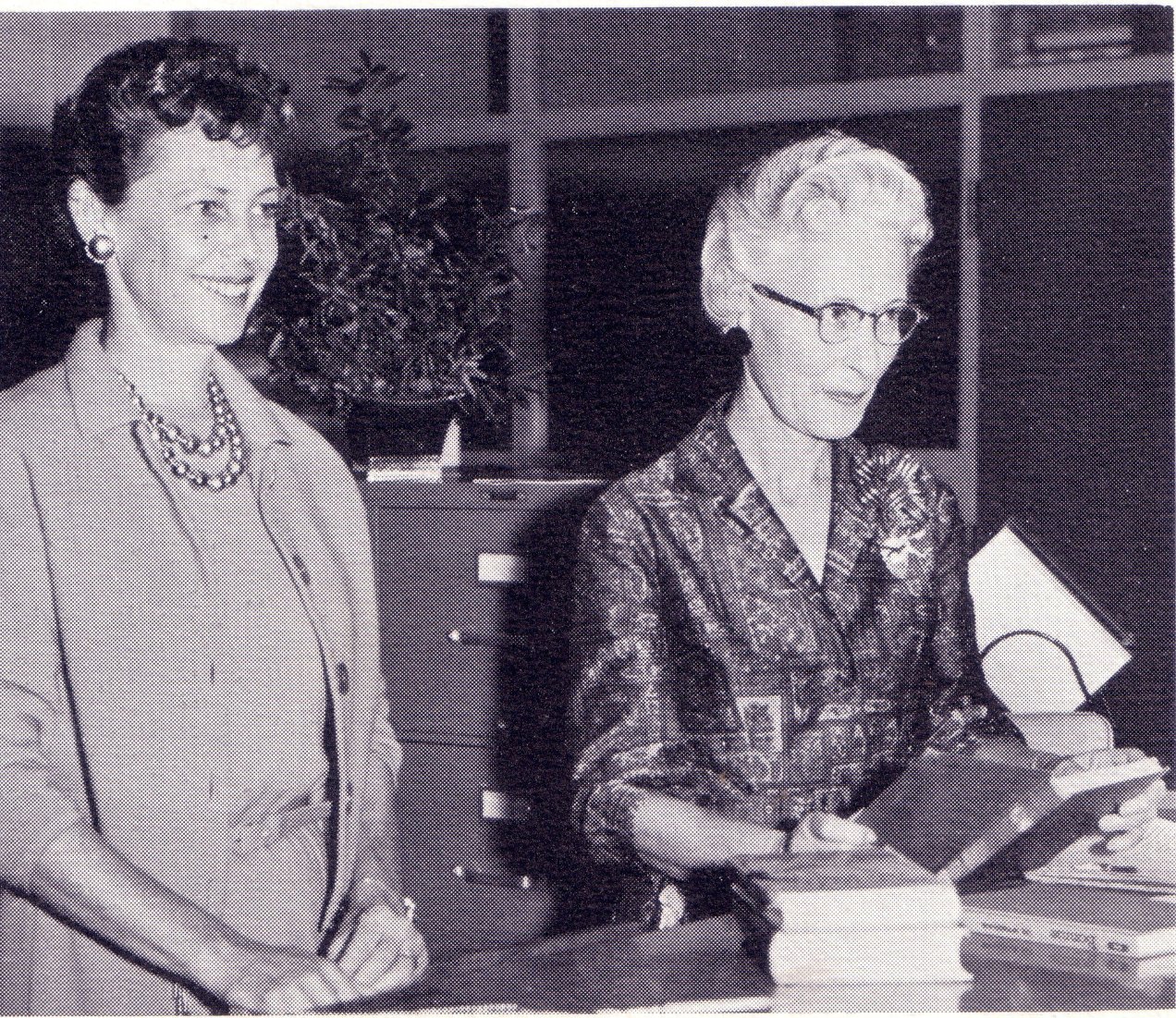

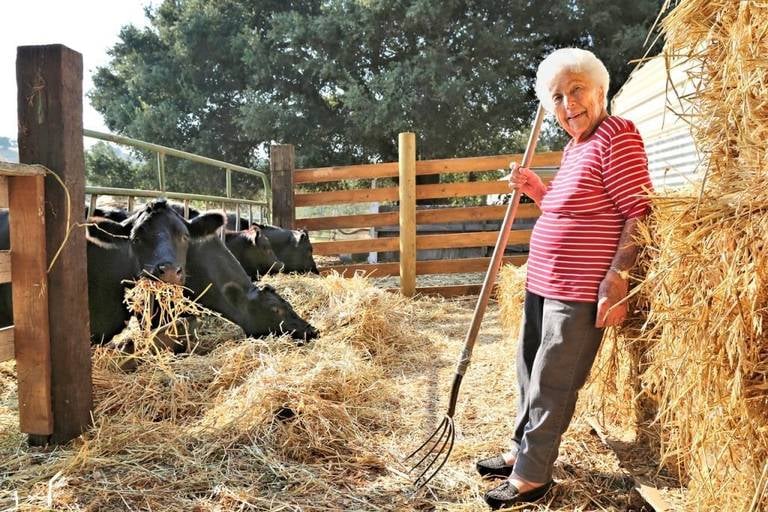

Jeanette (Shannon Family Collection)

Jeanette (Shannon Family Collection)