Michael Shannon.

For a good start, be sure to be born on Easter Sunday. You might want to be the only child, a boy child at that, born that day. You should be born at Our Lady of Perpetual Help Hospital, better known as Sisters Hospital.

Staffed with The Poor Clares an austere Roman Catholic religious order of nuns, co-founded in 1212 by Saint Clare of Assisi and Saint Francis of Assisi. The order is dedicated to a contemplative life of prayer, and poverty. They were all good Irish girls. Many of them spent their entire working lives in Santa Maria and when they retired they returned to Ireland from whence they came.

They delivered the newborn to my mother with a blue bow tied in my blond locks. They told my mother it was an omen from God. It must have been because Dr. Case had given my parents some very bad news the year before, he said, “Barbara you will never be able to conceive.”

Born on Easter Sunday? Perhaps a subtle message to Harold Case. Who knows.

So thats a good start.

Now be sure your parents are from Farm and Ranch families. There are scads of reasons for this. The first is general health. To build a child’s immune system it’s important for them to drink from the irrigation ditch and the hose. In my case we drank from the kitchen faucet too, even when the water tank had dead Screech Owl chicks floating in it. The hard water in the valley had coated the inside of irrigation and all the other water pipe with a whitish hard scale that eventually caused the kitchen faucets to close up to the point where you could not stick a pencil in them. A soupcon of fertilizer in the irrigation pipe was good for kids too.

We learned that planting Roly-poly bugs does not grow snapdragons but that Nasturtiums are pretty tasty. We had oodles because they grew insanely lush over the septic pit behind the house. Leaves of three. let them be, we learned that the hard way and that Horse Nettles could be touched in the center of the leaf but not on the edge. We learned to remove our socks in the presence of foxtails and cockle burrs, that is if we happened to be wearing them and that there was only one kind of bad snake. If we saw one in the yard we just told mom, the woman whoo was terrified of spiders and she would come out and dispatch it with a shovel something she learned growing up in the oil fields. Mice in the house were pretty OK; Dad said they didn’t eat much anyway.

Kitties were tolerated for their mouser abilities but seldom coddled, dogs were loved beyond any reasonable amount. Dogs went everywhere we did, showing us the way.

I learned to swim in the creek and the watering ponds on the cattle ranches. I could throw tomatoes, bell peppers and dirt clods with deadly accuracy. It was a mile walk through the fields and a dirt clod fight could and did last the whole way. My friend Kenny and I stalked Old Man Parrish’s apple orchards with our Red Ryders. Everything we did was a made up game of the imagination.

Every old building, corn crib, horse barn, tractor shed harbored an army of spiders. The dark places were home to Black Widows. There were Tarantulas living in holes in the ground, The Daddy Long Legs, so delicate and harmless, the Orb Weaver who weaves those delicate circular webs that can be so striking in the morning when dripping with the morning dew that are so striking that we used to duck under them so as not to harm them. Besides they were natural born fly killers. The nasty brown recluse which, if it bit you it was a sure trip to Doctor Cookson’s office.

When Warners came to dust the crops with clouds of sulphur and DDT filled the air. Not unpleasant odors went you sniffed it floating on the breeze. Sulphur was sprayed on Tomatoes and peas to fight mildew and DDT. It just killed everything but kids. We could imgine WWI watching those old Stearman biplanes zooming ten feet off the ground and then pulling nearly straight up after flying under Lester Sullivan’s power lines. He flew a Chandell and came right back the way he came and did it again. Dad said he was WWII fighter pilot and wishes he still was. He would call the kitchen phone to say when he was leaving Santa Maria so we knew when to rush out and get as close as possible to the crop he was dusting.

When we were big enough we stood on the cultivator bars of my dads tractors to hitch a ride into the fields. This wasn’t thought of as any great danger. Two of us would jump up and down on the bars to make the tractor buck a little which dad never seemed to mind much. Falling, losing your grip or footing and being dragged to death seemed a small price for some adventure.

We dug in the dirt, wallowed in the good rich mud of our adobe fields. Mom said the clogged pores in our skin prevented germs from entering. Being hosed of on the front lawn wasn’t such a bad thing in the summer.

The families ranches introduced us to livestock, “Bob” wire fences, the wonderful cow flop, cows must have the biggest bladders on earth. Have you ever seen a steer pee? My goodness! We knew what a salt block tasted like. The smell of new mown hay, used all the time in poetry but I think seldom experienced by most, the feel of the curly hair on a Hereford calf’s head and the rough feel of a cows tongue when she gives you a kiss.

My mother made sure we had a good clean shirt every day but Levi’s were worn until they were dirty and greasy enough to stand on their own. I mean, she had an old Westinghouse tub style washer with a wringer on the top which we were warned about but that hardly mattered and the occasional fingertip was squshed, carefully, so just to see how it felt. No one minded hanging out the wash because the clothsline was a great place to run through when the clothes were till wet. Had to be careful though, that was a switching offense. If you ran though and made good your escape mom soon pardoned you with a hug and a promise not to do it again.

Kids did get sick though. We got infected from the other kids at Branch school. In the winter. Mrs Brown’s lower grade classroom could at times be fogged with microscopic beads of snotty goo and desk tops were glazed with phlegm from sticky fingers.

Mom and dad took disease very seriously. We had all the modern doctor mom tools, the humidifier that chuffed a fog of Vicks Vapo-Rub mist, A bottle of Iodine, Aspirin and band-Aids. She kept a handy rubber hot water bottle and if it was serious you might repose in their bed during the day and simply be cured by that treat and the smell of them as you slipped in and out of your fever dreams.

Our parents grew up in an age where the death of children was an omnipresent occurrence. When my father was born, one in five children died before their fifth birthday. Smallpox still wasn’t eradicated though the vaccine had been around for more than a century. My dad nearly died from Scarlett fever when he was seven. There was no cure. Children died from Whooping Cough, Measles, Influenza, Pneumonia, and infections from ordinary cuts and scrapes. A broken bone could become septic and a child would be lost. If you lived in the country there was little access to medical care, schools did not have nurses in attendance. The life of a child was precious but there were few ways to protect them. My own aunt was infected with polio when she was just nineteen. She survived but had a game leg for the rest of her life. Did I mention he was married with two small children and pregnant with a third when it happened.

Today we seem to have lost the institutional mamory of what pre-antibiotic medicine was like. My parents never did and neither have I.

No one asked me if I wanted to be stabbed by the nurse from the County Schools Office as we lined up at the schools gate and waited in line to go up the steps of the little school van and be stuck. Nope, any squawking would have been completely ignored. Parents knew the cost, nobody complained.

We learned from our parents that most things were not crying offenses. Dad never complained about anything, neither did my mother who if she sniped about her friends she didn’t do it around us. We lived in the kids world, all of us. Adventure was something homemade. You polished your imagination with no help from television because in the very beginning it wasn’t made for you. Reading was the drug of choice. We had all the Hardy Boys adventures, The Three Musketeers, Mark Twain, Jack London, Franklin W. Dixons Frank Merriwell’s adventures which in and of itself made us want to go to college. We knew little or nothing of war or politics. Those were of the adult world.

Looking back you can see that we were free to make our own adventures. We had little supervision. We knew the rules laid out for us but they were few. We were expected to have a good time, explore, learn to swim in the creek, fish for our dinner and follow the dogs wherever they went.

It was in many ways a simpler time for kids. You had time to learn and form yourself. To put on some the armor of self before you had to inevitably step over the threshold of young adulthood. It took me a long time to catch up with the town kids when I went to high school. I wasn’t prepared for smoking, fighting, sex or any of the other thing that can bring kids to grief.

A friend once told me that he found it admirable that I went my own way. Growing up on the farm had vaccinated me so to speak. Thoughtfulness was simply ground in you by experience. We were vaccinated by the tenet that you should “Look before you leap.”

Growing up on the land and understanding that the most wonderful thing was that my parents were alway there. My dad in our fields and mom in the kitchen. We were safe and secure in the knowledge that we were loved and cared for.

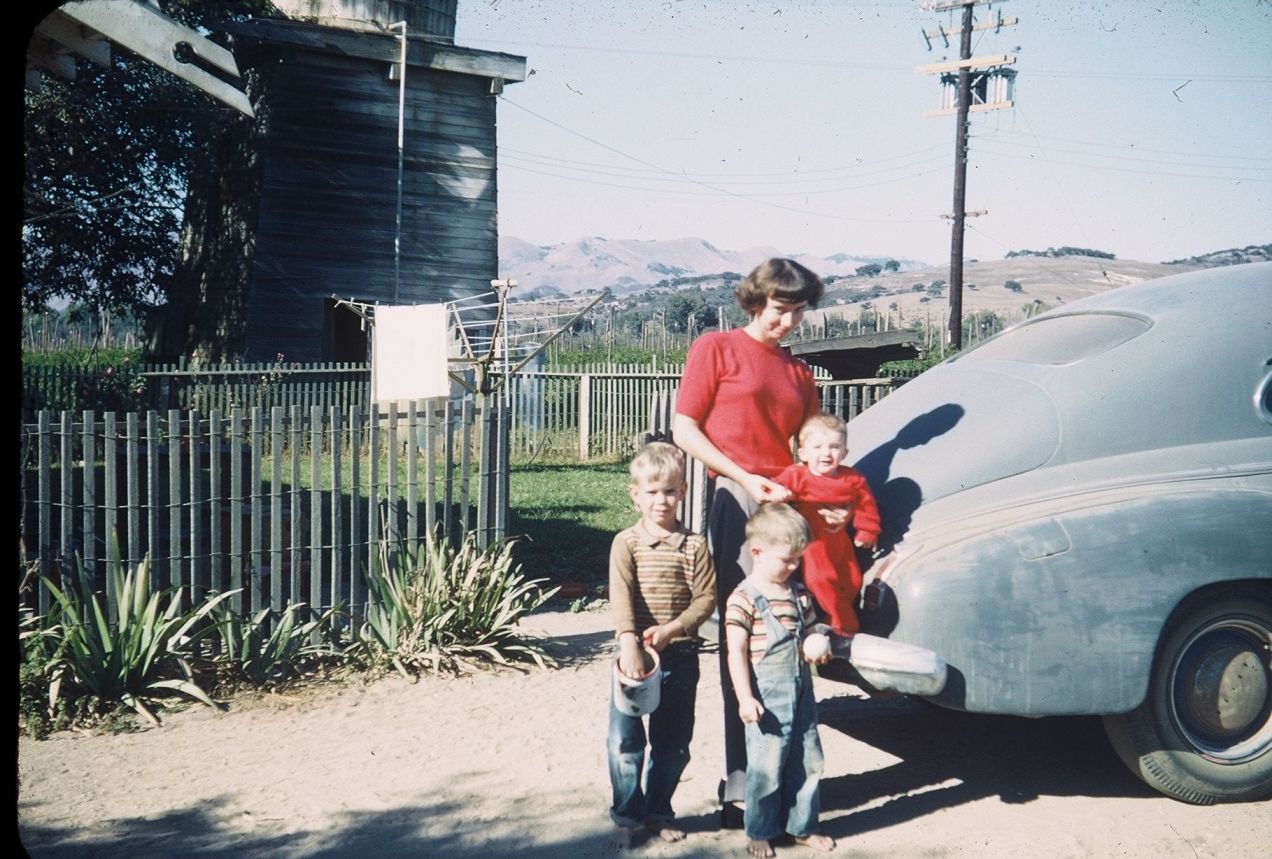

Cover Photo: My aunt Patsy at 17, she of the polio. My two brothers and myself. We were one, four and six. Shannon family photo

Michael Shannon is at heart, still a farm boy. He writes so his children will know where they come from.