Michael Shannon

I met Billie at the door. She had the Key. She handed it to me and I slid it into the old mortise lock on the side door and pushed it open. The rusted hinges resisted the movement a little but finally allowed us in. The narrow hallway ahead was redolent of dust and the peculiar smell I’ve always identified with old buildings. Ahead, the stairs to the 2nd floor lodge room were nearly covered on the left by stacks and stacks of newspaper galleys collected by the Historical Society from the old Arroyo Grande Herald. Some of the newsprint had come from former owner and publisher Newall Strother’s home on old Musick Road, found there upon his death stacked nearly to the ceiling in every room. A gift unintended, left us by a man who just couldn’t bear to throw them away.

Dim light with legions of dust motes drifted slowly in a tiny breeze from somewhere in the old building. Up the stairs there were windows at the second and third floor landings, lighting the stairs with the particular glow of dirty old glass, aged and coated inside with decades of smoke and outside by the grime blown against them by weather. A filmy yellowish khaki, gently drifting cloud that only exists in old unused buildings. It tinted all vision.

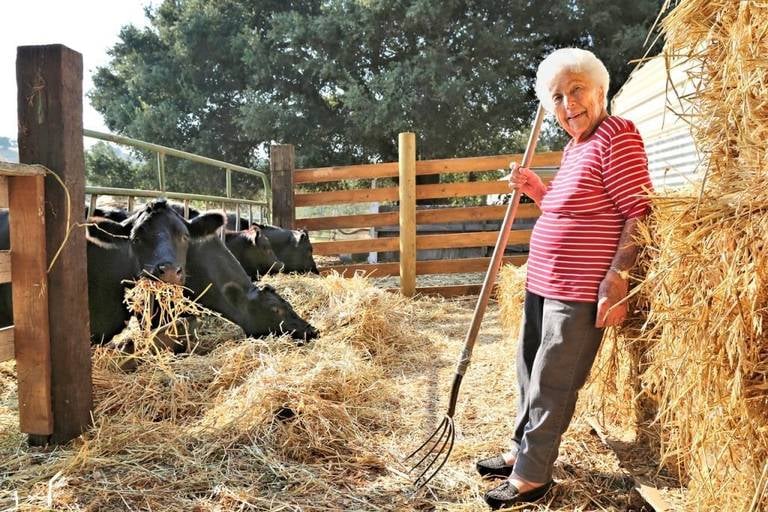

“Let me show you the lodge room, no ones been in it, I think, for many years,” she said. I followed the little woman up the stairs. Dressed in slacks, what looked to be a mans old dress shirt, girls old-fashioned tennis shoes, her grey and white hair taking a glow from the old windows, she led the way up.

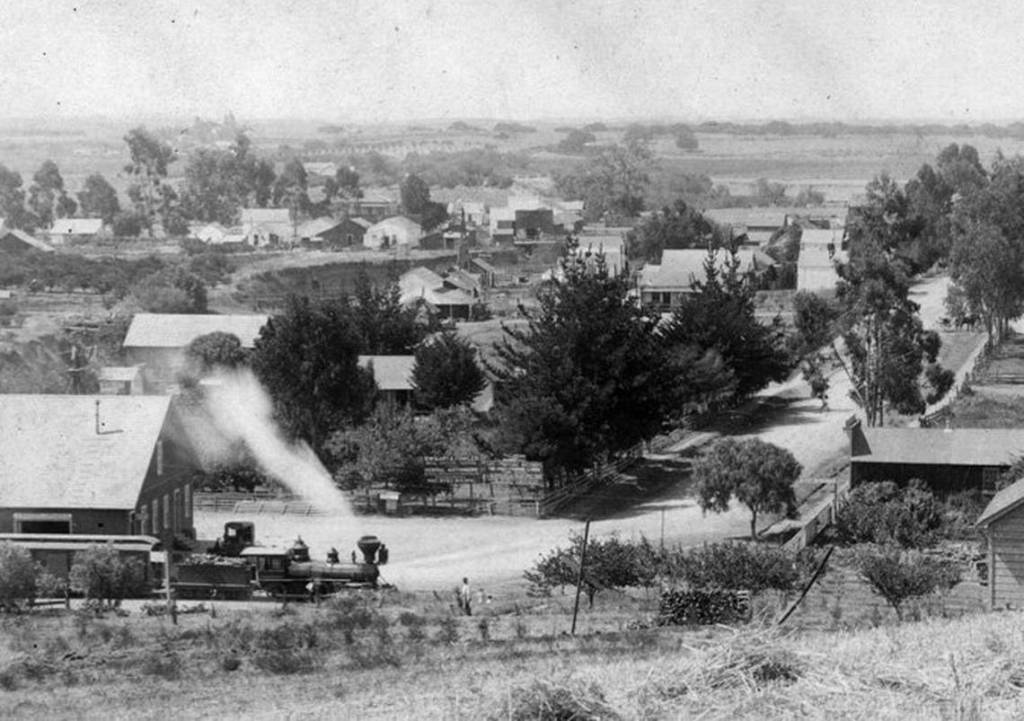

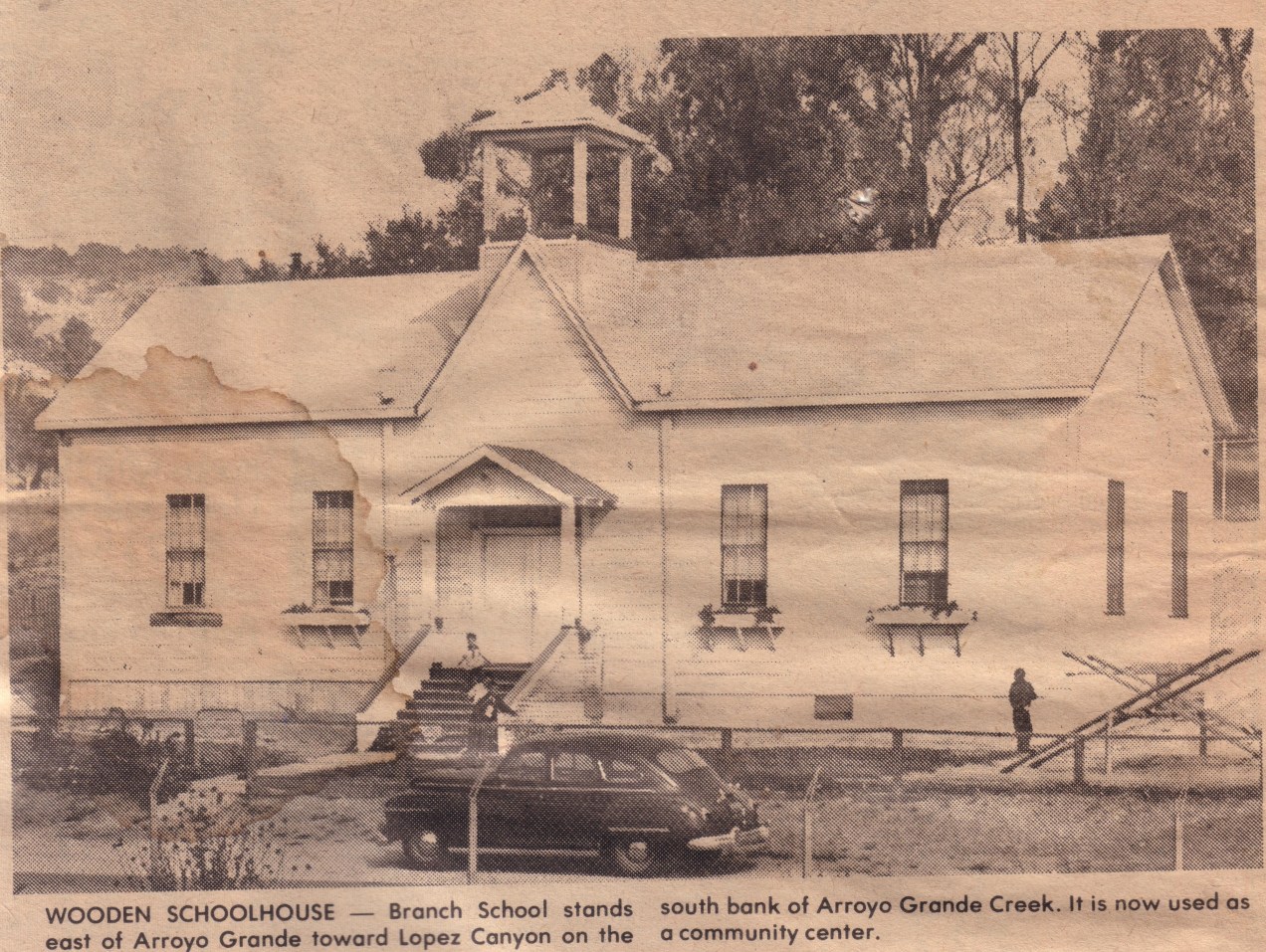

Her name was Billie and I had known her literally all my life. She was the granddaughter of Don Francisco Branch, the first of the Rancheros to bring his family up into the northern part of the old Spanish Cow Counties in 1837. He received a land grant from the Mexican government of nearly seventeen thousand acres of un-cleared nearly virgin land which had remained untouched by any but the few Chumash for thousands of years.

Billie’s father, Thomas Records, from another pioneering ranch family, had married Miss Lucy Jones, a granddaughter of Francis Branch. Billie was historical royalty in the little town we lived in. She kept things. My dad said that she and her sisters weren’t called the “Record sisters” without reason. She had a house full of stuff and a mind chocked to the brim with notions about who did what and how. She knew the bloodlines, the natural intermarrying of citizens in small towns. If you needed someones antecedents, she knew them.

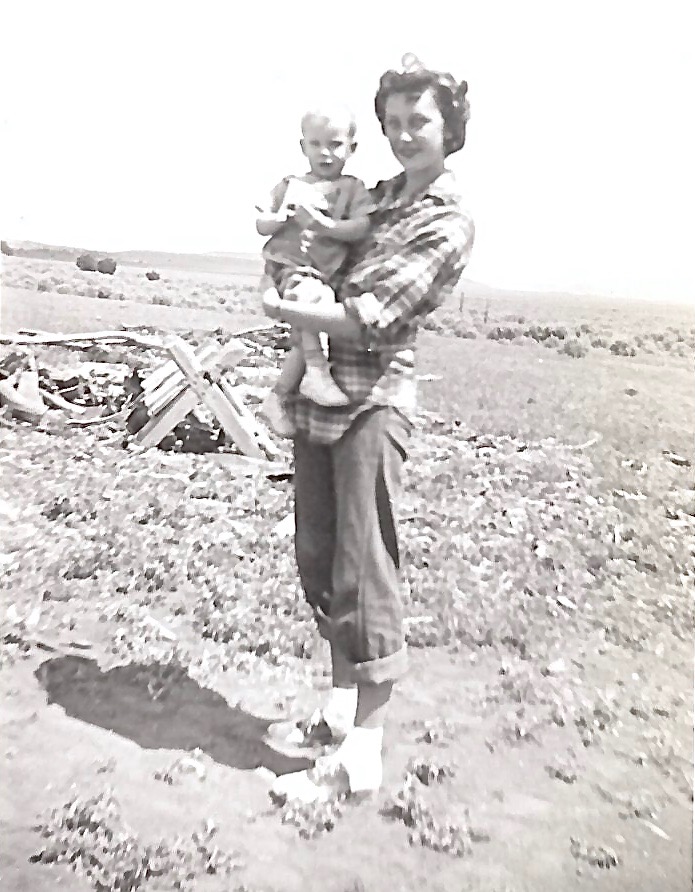

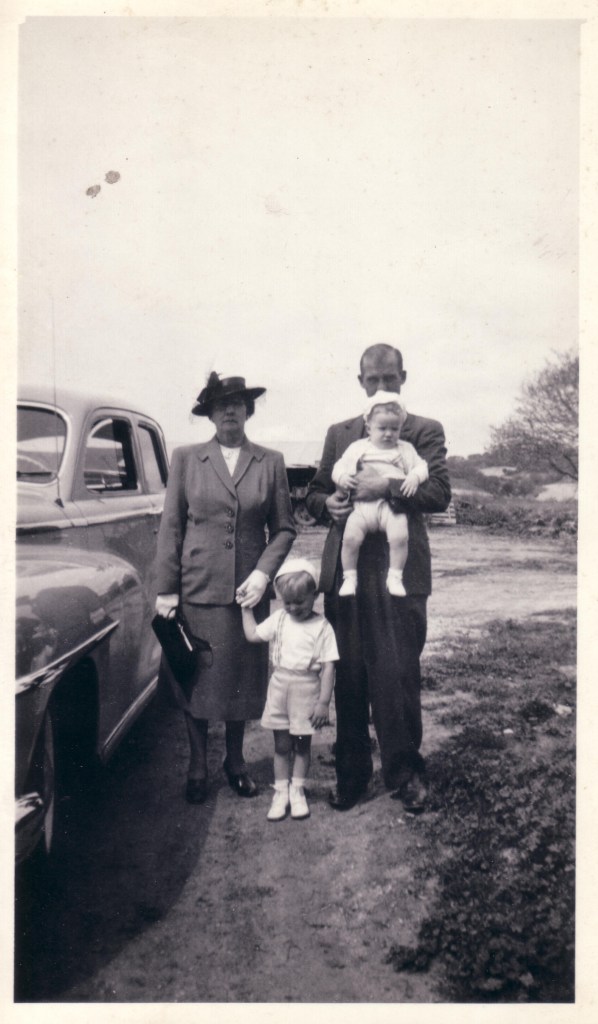

Me and Billie in Madeline, California 1946. She’s 31, I’m 1. Family Photo

She and my father grew up together and had always been great friends. When Dad found my mother, Billie took her right into the Arroyo Grande family. She was the kind of person that, when you saw her on the street there was nothing to do but to pull over and talk to her. After my father died she came to the house with a box of, you guessed it, records. She had squirreled away news clippings, letters and other things about our family. In the box were my fathers high school football and basketball varsity letters. She had put them away and saved them for seventy years. That’s a story I wish I knew. I’m sorry that I never had the chance to ask her or him why she had them. He went to Arroyo Grande High School, she, Santa Maria but somehow she ended up with them. There is a story there, lost forever I think.

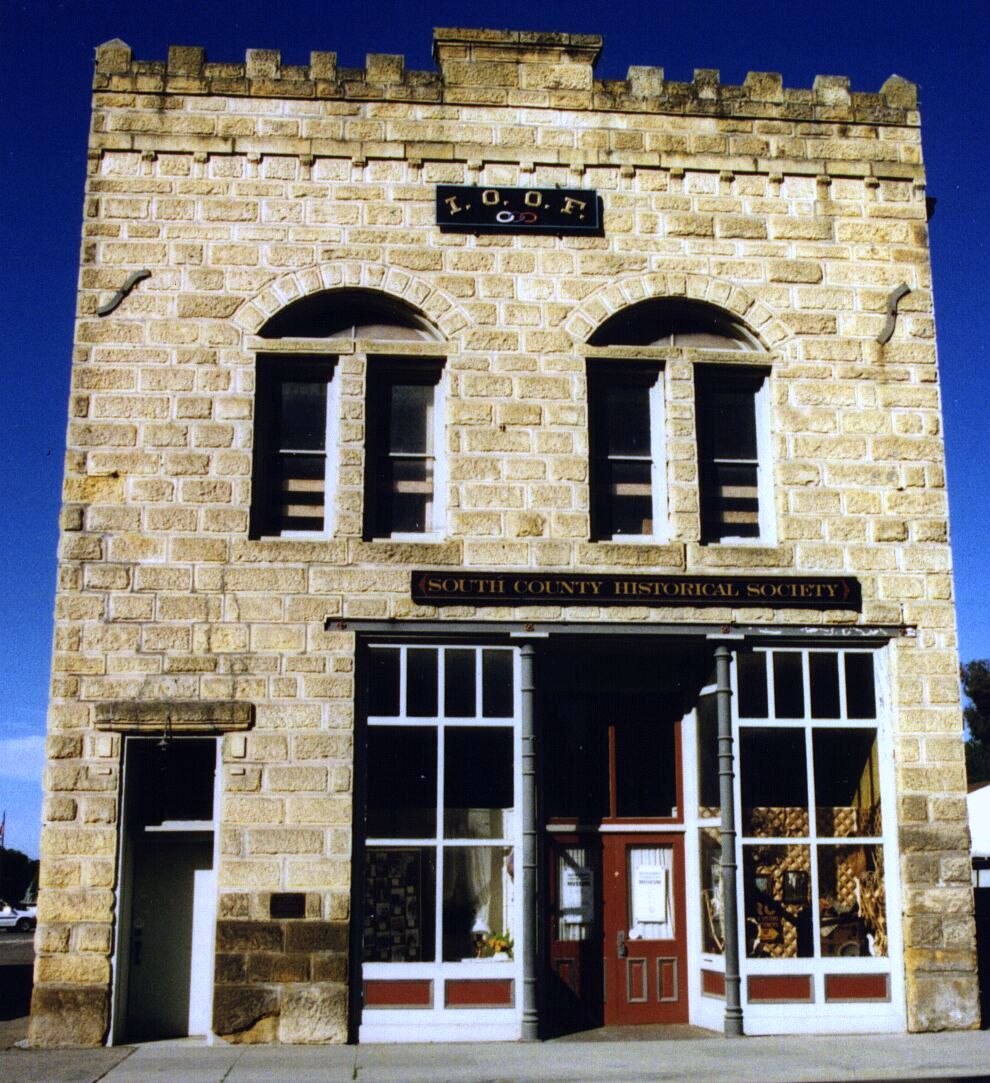

We were at the old hall, Odd Fellows 253, because as a new board member she wanted to give me a guided tour of the old building. The local History Society had recently received title to the nearly one hundred year old building for the grand sum of one dollar from the last surviving member, Gordon Bennett. The board and membership were fixed on the idea that we might secure funding to refurbish the old landmark.

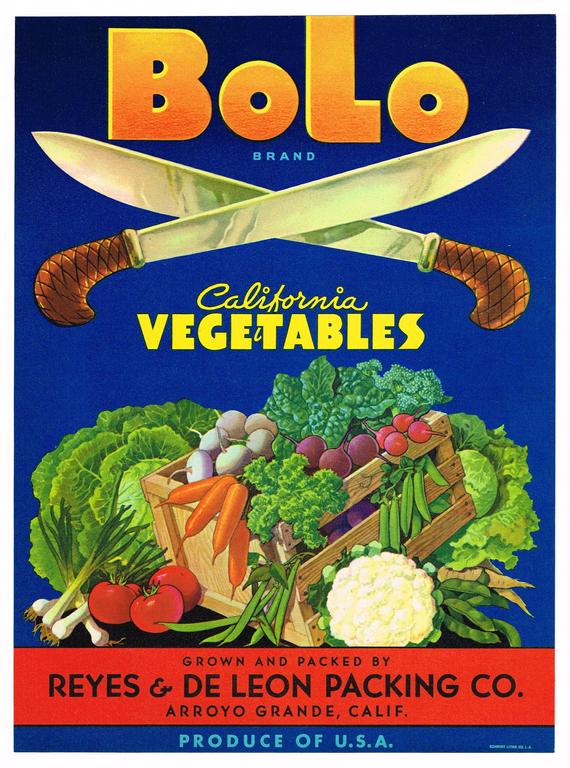

Built in 1903 as Lodge 253, the old building had lain vacant for years. The Arroyo Grande Sandstone of which it was made had come from the old Patrick Moore quarry on my grandmothers ranch.

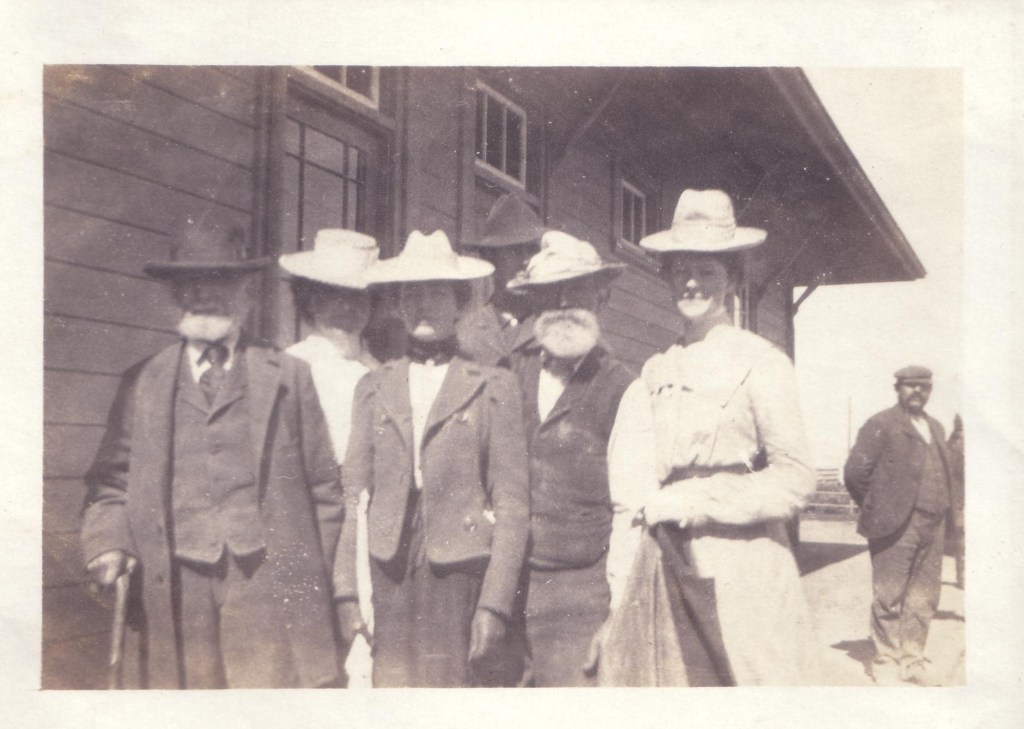

Left, Thomas Shipman brother in law to Jenny Gray, Annie Shannon in back with her mother Jenny and Maggie Phoenix in front of the hall.circa 1905. Family Photo.

We were at the old hall because as a new board member she wanted to give me a guided tour of the old building. The only time I had ever been in it was as a teenager. I had gone with my father to pick up his blue ribbon won for the best Chinese Peas at the Harvest Festival vegetable contest. The local farmers display of all the different vegetables grown in our valley took up the entire first floor. While we were there he pointed to the big windows in the front of the building and told me that my great-grandfather Shannon’s body in his coffin had been displayed there when the ground floor was the towns undertaking parlor. What does a kid say to that, I couldn’t imagine such a thing but I’m sure it was true, they used to do things like that. He said my grandfather who was a member of the Odd Fellows had taken him down when he was just twelve to see Dad Shannon, as he was called, as his body lay in state. In the window, not a church, but in a window.

The local History Society had recently received title to the nearly one hundred year old building for the grand sum of one dollar from the last surviving member, Gordon Bennett. The board and membership were fixed on the idea that we might secure funding to refurbish the old landmark.

At the first landing a quick turn to the right led into the lodge room. This was where the members met. It was obviously well used, the old carpet was faded and threadbare in places. The benches along the walls had seen better days, their varnished seats rubbed bare by generations of shifting bottoms. The curtained windows their muslin drapes transparent and fraying at the bottom filtered the sunlight creating a sense of timelessness as if the members had just left. I suppose they just had in a way.

The tour finished we turned and stepped onto the landing to head back down. I stopped and asked Billie where the next flight up went and she said it’s just an old storage room I think but you can look if you like. She turned and headed down, I turned and headed up the short flight. Just curious.

The door was closed, the old stamped doorknob mounted in its long rectangular faded brass plate turned stiffly. As the door tuned on its hinges the unmistakable odor of age greeted me as I stepped inside the dim interior. It wasn’t a storage room at all. Festooned with cobwebs nearly invisible in the gloom was a full sized six pocket pool table. Covered with the dust of decades it’s woven leather pockets still held the ivory balls fallen there during some last game played long before my birth. Two pool cues embedded in the cobwebby drift of aged dust lay on the felted top as if the players had just left for a meeting downstairs. Scoring beads hung from a long leather string indicating the final score. Overhead was a gas light fixture, its copper tubing rising to the ceiling and from there to a brass valve on the wall. Each burner had a age caked glass chimney under a brass shade, four of them once providing light to the table. Near the door was an ancient porcelain mercury switch that controlled a single light bulb hanging on old, old Ragwire directly over the sink. Electricity must have been installed sometime after the gas fixtures. A back up I suppose.

The sink was simply an enameled iron square basin. It was cradled in a pair of iron, triangular brackets mounted to the wall. The rusted old brackets had the image of a camel suspended in the frame. The drain was straight and likely just ran outside the wall and down the side of the building, simple and practical.

A small table and two cane backed chairs stood guard, one with a frayed seat. One old glass stood solemnly on the table, the bottom holding the dried remnants of whatever it held last.

A shiver ran down my spine. This was the place members retired to have a nip, play some pool and share stories, smoke or chew a five cent cigar. A place where hats didn’t have to be removed for ladies, for there would have been none. Breath slowly, squint a little and you can see Judge Webb Moore lounging in a chair tipped against the wall as Jack Shannon and Hu Thatcher chase the ivories around the table. Warren Routzhan and Ben Conrad confer in the corner, waiting their turn while Fred Jones and Harold Howard laugh over a George Grieb Joke. No Odd Fellows title needed here, no Noble Grand, no Rebekahs just some good hard working men sharing their time.

None of them would have been caught dead in a real pool hall for they were respected members of the little community they lived in. Here, on the third floor hideaway the rules were different. as they should be.

I waited a bit, then quietly closed the door knowing that I had surely caught a ghost.

Michael Shannon and his extended family have lived in Arroyo Grande, California for six generations.

Jeanette (Shannon Family Collection)

Jeanette (Shannon Family Collection)