Michael Shannon

In the 1950’s when I was in elementary school, a child’s self-esteem was not a matter of concern. Shame was considered a spur to good behavior and accomplishment. If you flunked a test, you might be singled out, and the offending sheet of paper, splattered with red marks, was waved before the whole class as a warning to others, much the way in which ranchers hung the carcass of an offending coyote across a barbed wire fence as a warning to other coyotes.

Fear was also considered a useful tool. In those post WWII days, we were all raised by parents and a society in which was engrained the sort of discipline, not applied with a stick, but rather, the strictures one learned by the seemingly endless depression and the world wide war that followed it. Both events required strict rules that applied to almost all parts of our parent’s lives.

They had been tempered by the depression and had the scars to prove it. Many of them had grown up without enough to eat, with holes in their shoes, ragged shirts and trousers; radios, decent cars and a complete education cut short by the depression or the war. When it came, they were not soured by their experience, but rather still looked on their country as something to love, something special. They came out of this experience self reliant, not afraid of hard work and used to taking orders. They had a sense of worth and self confidence.

We were fortunate enough to be their children.

Teachers were inviolate. Their word was law, and never in my eight years at Branch, did I ever see a parent be other than polite and solicitous to a teacher. In those days, a teacher was not suspect at all, she took care of a child’s education, both academics and social. My parents considered themselves honored guests at school and under no circumstances would they take my word in a dispute. I wouldn’t have dared. You see, there was no principle or administrator, just the teacher and she was the be all and end all for all things school.

At my school, a two-room wooden building, far older than a half century when I went there, hard working parents provided the foundation for teachers in every sense of the word. The teachers taught and the parents supported them. Repair and maintenance of the old building was done by volunteer labor and she was kept in pretty good shape for an old girl. Better, in some cases than the homes kids came from.

Two teachers taught about 50 kids in all grades. Divided smack in the middle by a hallway, the two class rooms were entered by doors tucked in between coat hooks, trash cans and tall cabinets in which were tucked the essential tools of the teaching trade. Grade level books, spare erasers, boxes of chalk; for we still used slate black boards in those days, Rags, cleaning supplies and the detritus accumulated over eighty years of use. Mrs Edith Brown taught first through fourth and Miss Elizabeth Holland, a spinster lady, taught fifth through eighth. Mrs Brown had just arrived a year or two before me; 1949, to be exact, after a long career teaching at the Arroyo Grande grade school on Orchard St. The home of kids we referred to as “Town Kids,” somehow sensed as inferior to us. They on the other hand referred to us as “Farmers,” Most certainly a perjorative term, usually accompanied by a sneer.

Miss Holland taught her entire career at Branch. Until almost her 35th year she taught alone. Only at the twilight of her career, was a second teacher assigned as enrollment increased school population; the beginning of the “Baby Boom,” and the closing of nearby Santa Manuela school made the classes too large for a single person.

Branch school had been moved from a previous location by the expedient of jacking it up, sliding peeled logs beneath it and hitching the entire contraption to a team of horses, then dragging it wherever you wanted it’s new home to be. In our case, a hollowed out side-hill near the old Branch Family cemetery on the original Santa Manuela Rancho in the upper Arroyo Grande. Behind and to the right was open, oak studded pastureland, complete with the occasional Hereford. To the left, a scattering of homes, mostly small and fairly recent. Across Branch Mill road was the Ikeda brothers reservoir, a small fenced pond in which the gate was never locked. Tthe creek, was about a half mile down the hill. Across the creek lived the Cecchetti family. Gentle Elsie, big George and the legendary George “Tookie” junior. To the left, an expansive view of the lower valley, all the way to the dunes, fourteen miles away. The view explained, at least in part, why Don Francisco Branch located his home on a little hillock, less than a mile from the school. That building was long gone, having been built of adobe sometime around 1838, it had gently melted back into the earth from which it came. The site guarded by a pair of ancient pepper trees, whose seeds traveled across an ocean in a small bag carried by the Franciscan Fathers who found their way 2690 miles on foot to the site of the Mission, San Luis Obispo de Tolosa.

In the fifties we considered ourselves modern because we had a school bus. When I started school, it was a 1949 Chevrolet half-ton pickup, fitted with a brown canvas top, two wooden benches down the sides and a chain across the back where the tailgate used to be. You simply climbed up and over the bumper and perched where ever there was a seat. It had a roll down flap in the rear to protect kids from the rain. Why I don’t know, most kids had to walk from home to the bus stop no matter what the weather. Our house was about a quarter mile from the back door to the mail box where we were picked up. In the winter that driveway, if I can dignify it as such, was slimy with mud and puddles that reached little boys ankles. I still recall the ritual of using a kitchen knife to scrape as much mud as you could from your shoes and then putting them in the oven to dry. The next morning, shoes were dry, but as stiff as an old hide and had to worked about in order to make them soft enough to wear. In case you missed the part about the kitchen knife, yes, they were the same ones we ate with. No one seemed the least concerned about that. Just a job that had to be done.

Our bus driver was Mrs Evelyn Fernamburg. She did duty as the bus driver, janitor, school board member and 4-H leader. You see, Branch was its own, independent school district. It was almost entirely a volunteer operation. The county school office provided the budget and thats all you got. The budget came almost completely from property taxes and after the county skimmed off the lions share, schools received their allotments. School board members used funds for improvements, teachers salaries, the bus and driver, and then did the rest of the jobs for free. They built the monkey bars, teeter totter and carousel on weekends. There was no lawn and the playing fields were simply scraped out of the hill sides. No child of the fifties will ever forget that, in order to save money on the continual painting of the old redwood siding, which was a big job, the board decided to cover it all with a brand new innovation, asbestos shingles. An off pink color, they solved the problem of repainting but, of course, they were asbestos. Didn’t seem to hurt anyone though and the school was well known for its “wonderful” color.

Behind the school were the restrooms. The term restrooms is applied loosely. Both boys and girls were in a small green shed, divided in the middle with the girls on the school side and the boys on the up hill end. Neither had a door, only a little privacy wall to prevent any immodest peeking. They both had a toilet with a wooden seat. In the fifties they had dispensed with old phone books and stacks of small squares cut from newspapers and used what my dad called window pane toilet paper, you can guess what that meant. Each room had something unique. The boys had a urinal or rather a trough for them to use. It was a galvanized thirty gallon water pressure tank cut in half lengthwise and bolted to the wall. A piece of half inch diameter pipe, drilled with a series of small holes and a gate valve at one end, completed this modern marvel. The girls had something even better; Bats. Boys, of course, knew all about bats and how the would lay their bat eggs in little girl’s hair. Mass screaming during recess would bring whichever teacher was closest, running to the bathroom with a handy broom to chase the bats away temporarily, at least. We boys took an unusual amount of pleasure in this.

One of the things that we didn’t realize until we were much older was, with only a few kids of any age, every activity from classroom study to recess and organized games required all ages, six to fourteen. All grades were together for every thing we did, be it a school play, softball or jump rope. Each game had its season, none marked on a calendar, but mysteriously appearing when the time was right. Suddenly, in the spring, marbles. The jump ropes, dormant in the old closet that served the athletic gear, brought out for the two weeks that jump rope was in vogue. In our school this was not just a sport for girls. There was no PE. Groups of kids just decided what to do on their own. There was almost no adult supervision, kids were expected to use their imaginations. Older girls might stay in during lunch and listen to records they brought from home on the little portable record player that was kept in the closet. Oh, the wailing and crying in 1959 when the Big Bopper and Ritchie Valens were killed. Lulu, and the Judy’s were fit to be tied. A terrible tragedy when you are just 13.

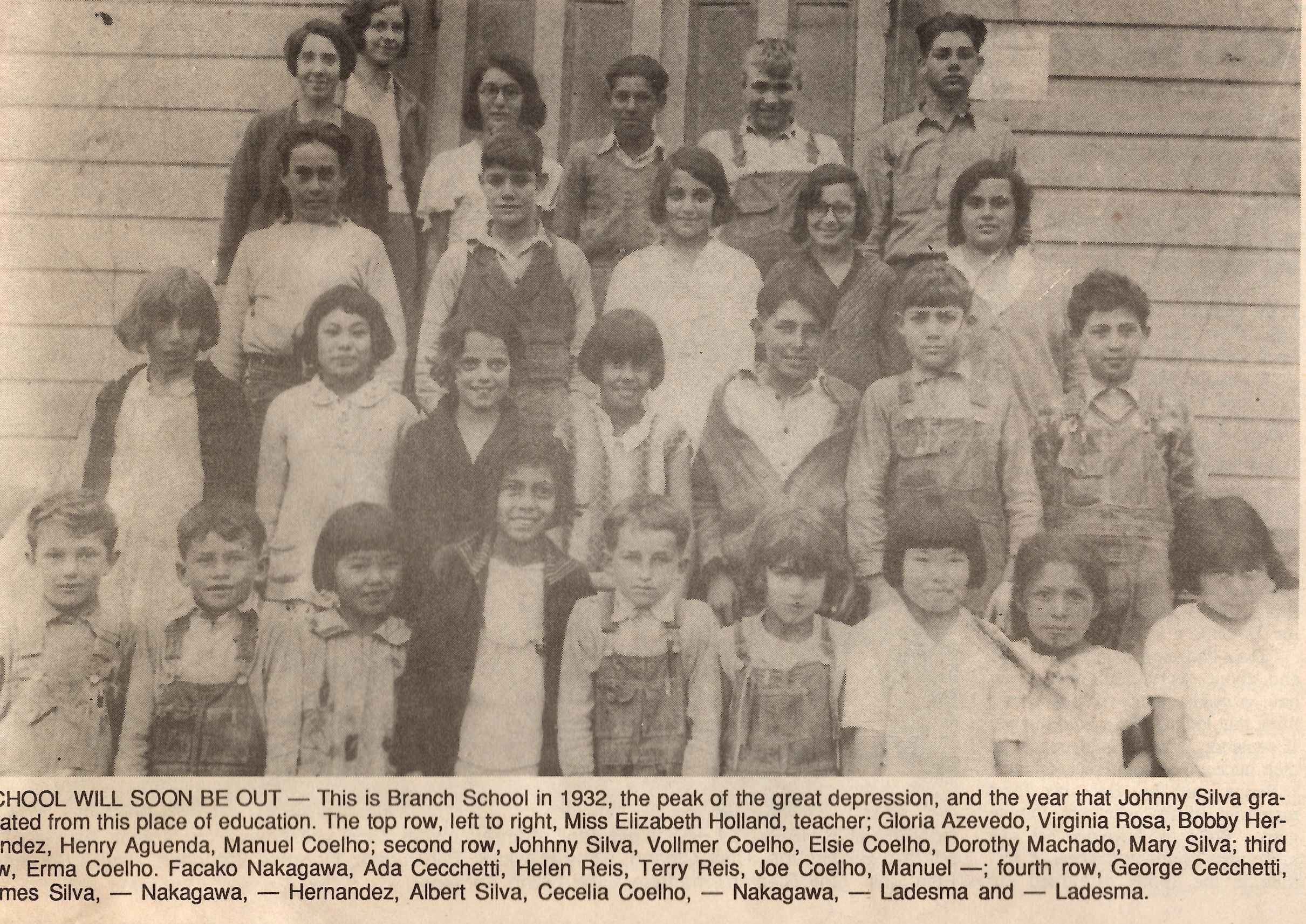

I never heard a teacher or parent discuss curriculum. We were taught the basics of math, social studies, California history and we read, a lot. With perhaps 30 kids, Miss Holland supervised four grade levels all at the same time. When giving lessons to one grade level she left the others on their own. We helped each other. Books were kept for a long time not traded in for new ones every couple of years. I used a social studies book in 1956 that was used by William “Bill” Quaresma in the 1930’s. I used a reader with the name Al Coehlo on the flyleaf. His son Al Jr was just a year behind me and used the same book as his father. History doesn’t change much, the teacher could fill in the blanks. Lest you think our teachers weren’t very good, The county schools superintendent told my father that Miss Holland was the finest teacher in the county in reply to a parent complaint. She had polio as a young woman and walked with a pronounced limp and used a crutch when she was tired. She was so very kind to all of us kids and I’ve thought through the years that those hundreds of kids she taught must have been her true family. My mom took me with her when she went to visit her on Pine St in Santa Maria a couple years after she retired and she seemed somehow diminished, as if the school was a part of her that was lost. She died in 1965, just 58 years old. In the picture at the head of this story, she is 47. She lived her whole life in that house on Pine St, she never married. We were her children.

All in all I was treated with kindness, which was often more than I deserved. My public school education has stood the test of time, which includes both the lessons my teachers instilled and the ones they never intended.

On the front steps of Branch School, 1932. I went to school with the children of many of the students pictured above. Most of these children are second generation immigrants whose families were working, renting or buying the rich farmlands of the Arroyo Grande. Mostly Portuguese from the Azores or South America whose families came to this country in the surge of immigration from the islands after the 1880’s. The Japanese families arrived about the same time, post 1880.

My own classes in the 1950’s weren’t unlike this one. We had some of the same surnames. We were Italian, Portuguese, Mexican, Irish, English, Filipino and Japanese. Quite a hodgepodge. My eighth grade class had four, the two Judys, Hubble and Gularte and the two Mikes, Murphy and Shannon. Our teacher, the same Miss Holland.

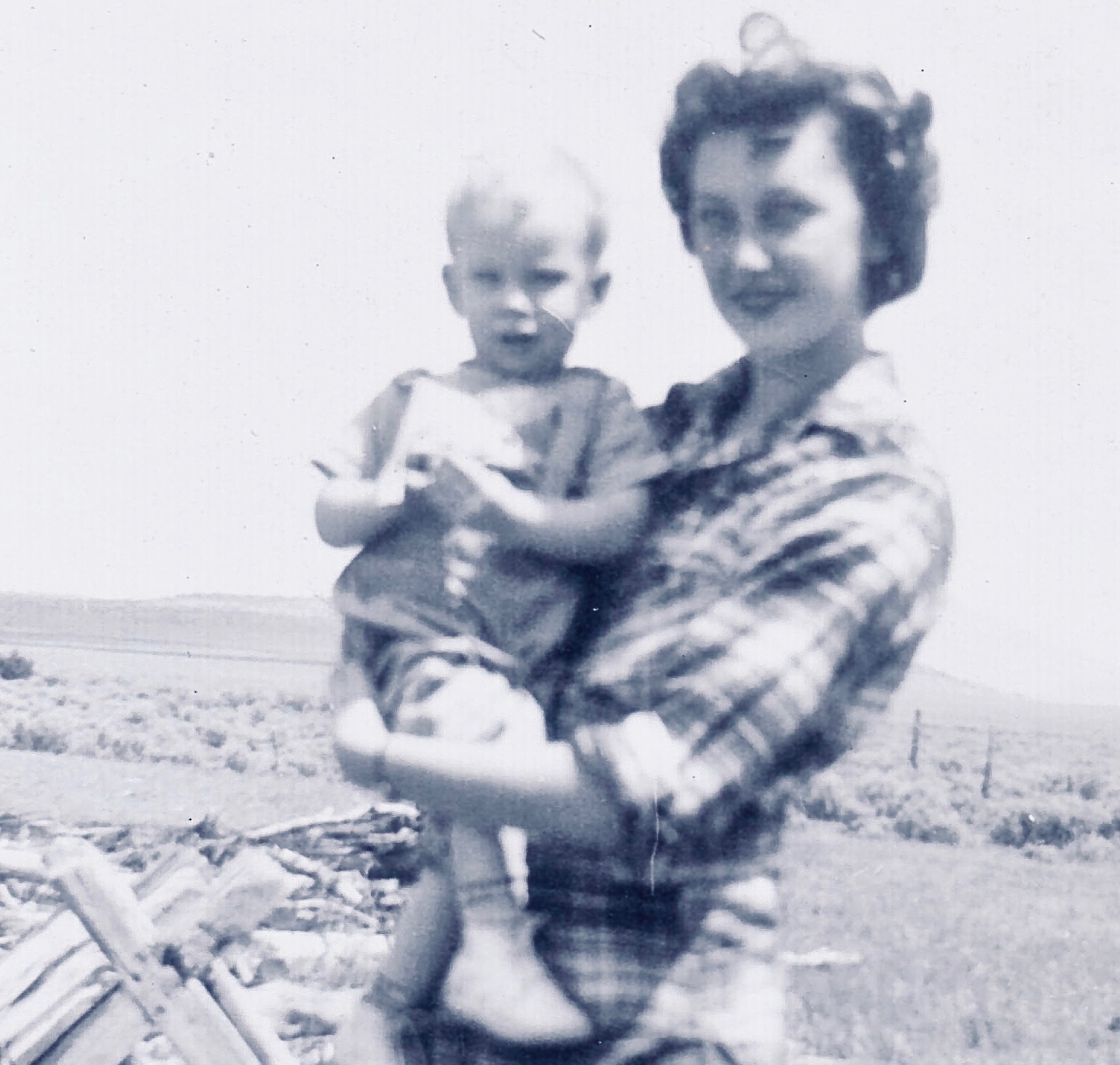

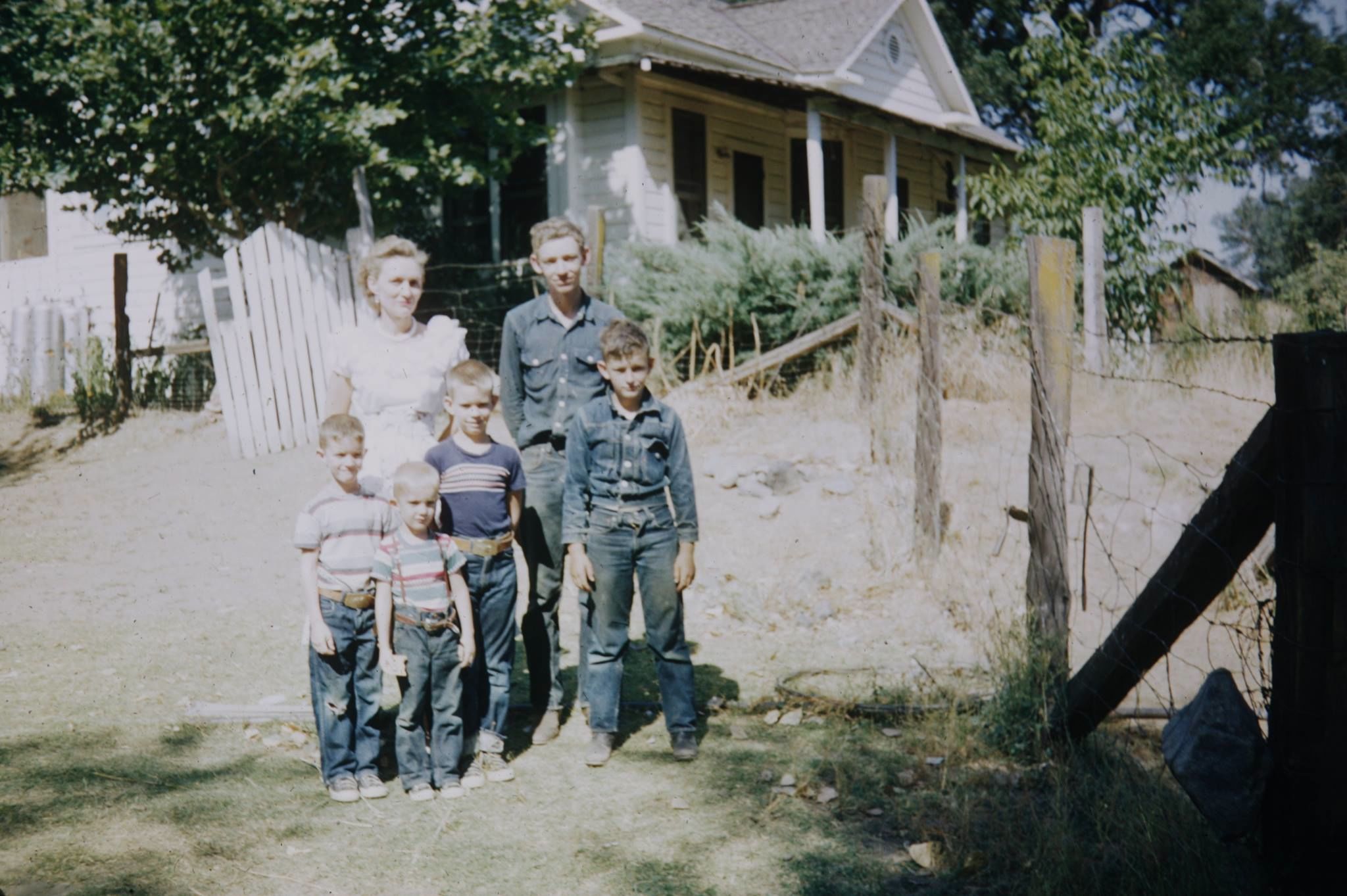

credits: Cover photo, 1956, Back Row, l-R Dickie Gularte, Jerry Shannon, Irv “Tubby” Terra, Georgei “Tookie” Cecchetti. Front, Patsy Cavanillas, Doreen Massio and Irene Samaniago. The entire fourth grade class.

Michael Shannon is a former teacher himself and damn proud of it. I hope Miss Holland and Mrs Brown know I turned out OK.